- Altmetric

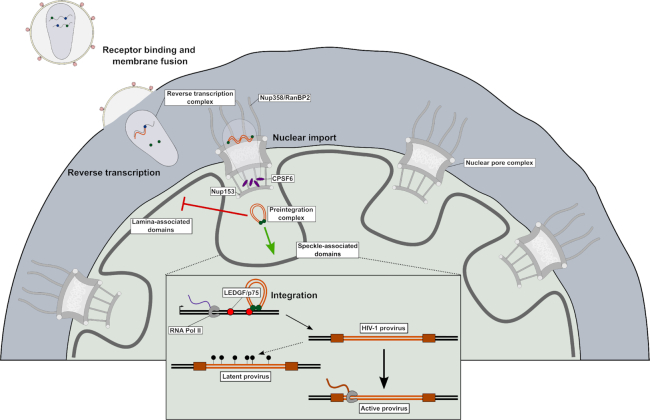

The integration of retroviral reverse transcripts into the chromatin of the cells that they infect is required for virus replication. Retroviral integration has far-reaching consequences, from perpetuating deadly human diseases to molding metazoan evolution. The lentivirus human immunodeficiency virus 1 (HIV-1), which is the causative agent of the AIDS pandemic, efficiently infects interphase cells due to the active nuclear import of its preintegration complex (PIC). To enable integration, the PIC must navigate the densely-packed nuclear environment where the genome is organized into different chromatin states of varying accessibility in accordance with cellular needs. The HIV-1 capsid protein interacts with specific host factors to facilitate PIC nuclear import, while additional interactions of viral integrase, the enzyme responsible for viral DNA integration, with cellular nuclear proteins and nucleobases guide integration to specific chromosomal sites. HIV-1 integration favors transcriptionally active chromatin such as speckle-associated domains and disfavors heterochromatin including lamina-associated domains. In this review, we describe virus-host interactions that facilitate HIV-1 PIC nuclear import and integration site targeting, highlighting commonalities among factors that participate in both of these steps. We moreover discuss how the nuclear landscape influences HIV-1 integration site selection as well as the establishment of active versus latent virus infection.

INTRODUCTION

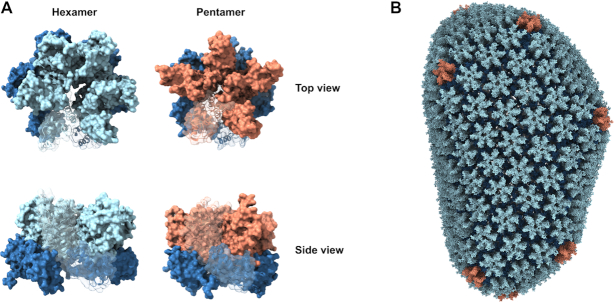

Retroviruses are enveloped viruses that contain two copies of plus-stranded RNA. The HIV-1 ribonucleoprotein complex, composed of the RNA bound by viral nucleocapsid (NC) protein as well as integrase (IN) and reverse transcriptase (RT) enzymes, is housed within a capsid shell made from ∼200 capsid protein (CA) hexamers and 12 CA pentamers (1,2). Together, these elements form the viral core. HIV-1 infects CD4+ cells including T cells and macrophages by fusing its membrane with the cellular plasma membrane (3). Once membrane fusion is complete, the core is released into the cytoplasm and reverse transcription ensues within the confines of the reverse transcription complex (RTC), a high molecular weight derivative of the viral core (Figure 1) (4). The RTC interacts with components of the cell cytoskeleton to enable its inward movement through the cytoplasm and toward the nucleus [reviewed in (5)]. Reverse transcription yields linear double-stranded viral DNA (vDNA) with several internal discontinuities amid the plus-strand (6,7).

Overview of HIV-1 cellular ingress and principle determinants of integration targeting. Infection is initiated by receptor binding and membrane fusion, which releases the viral core into the cell cytoplasm where reverse transcription begins. During reverse transcription the core is trafficked to the nuclear pore where it is transported into the nucleus via interactions between HIV-1 CA and several nucleoporins, including Nup358 and Nup153. Following translocation, CPSF6 frees the core from the nuclear pore complex and facilitates progression of the PIC beyond the nuclear periphery and into the nuclear interior. Integration is highly biased away from lamina-associated domains and towards speckle-associated domains, which are characterized by active transcription and high gene density. The interaction of PIC-borne IN with LEDGF/p75 directs integration into the interior of gene bodies. HIV-1 proviruses are typically well expressed by cellular RNA polymerase following integration. However, a small population of proviruses (marked by lollipops) are not expressed and become latent. These latent proviruses can be activated upon stimulation years after the initial infection.

A multimer of IN binds and bridges both ends of vDNA together to form the intasome nucleoprotein complex [reviewed recently in (8)]. Two IN activities, 3′ processing and strand transfer, are required for integration. IN hydrolyzes vDNA ends during 3′ processing to yield recessed CAOH-3′ termini, converting the RTC to the preintegration complex (PIC) (9) (Figure 1). After engaging a suitable target DNA (tDNA) acceptor site, IN uses the vDNA 3′-OHs to cut the major groove in staggered fashion, joining the vDNA ends to the resulting 5′-phosphate groups. The gaps between vDNA 5′ ends and tDNA 3′ ends in the hemi-integrant are repaired by cellular machinery to yield stably integrated provirus flanked by a short duplication (4–6 bp across retroviruses; 5 bp for HIV) of chromosomal sequence that was cut during strand transfer. A detailed overview of retroviral integration can be found in reference (10).

HIV-1 efficiently infects non-dividing cells (11,12) due to the active nuclear import of its PIC (13). Once inside the nucleus, integration preferentially occurs in regions of the genome characterized by high gene density and transcriptional activity (14). In particular, HIV-1 integration has been mapped to genomic regions in close proximity to speckle-associated domains (SPADs) and far from heterochromatin markers such as lamina-associated domains (LADs) (Figure 1) (15–18). These integration site selection biases are influenced by a number of factors, including interactions between the PIC and host proteins, the route of nuclear entry, chromatin accessibility, and local nuclear environment (16–25). In this review, we provide an overview of the factors known to influence HIV-1 integration targeting in the human genome. In addition, we discuss how integration site selection relates to the establishment of active versus latent HIV infection.

Access of cell nuclei by HIV-1 PICs

Nucleocytoplasmic transport

Because some of the host factors that help to determine chromosomal sites of HIV-1 integration also play roles in viral nuclear import, a review of integration site targeting necessitates a parallel discussion of PIC nuclear translocation. In this section we briefly review the process of cellular nucleocytoplasmic transport, paying particular attention to aspects that pertain to HIV-1. Readers interested in comprehensive reviews of cellular nuclear import are directed elsewhere (26,27).

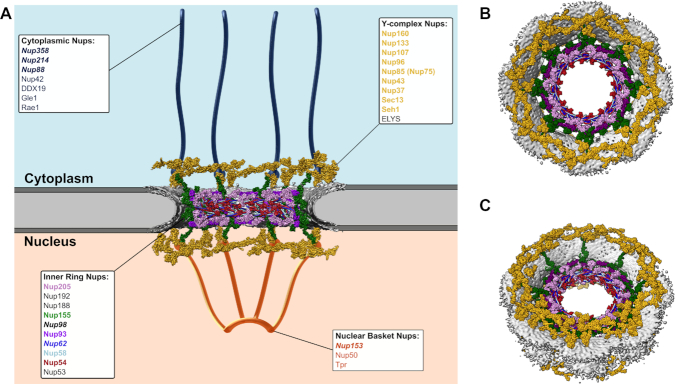

Nucleocytoplasmic transport of large macromolecules and macromolecular complexes is regulated by the nuclear pore complex (NPC), a huge ∼110 MDa assembly of ∼1000 proteins composed of 33 nucleoporins (Nups) arranged in 8-fold rotational symmetry [reviewed in (27)] (Figure 2A–C). The NPC is constructed from Nup subcomplexes referred to as the coat Nup complex or the Y-complex, inner ring Nups, pore membrane proteins (POMs), cytoplasmic filament Nups, and nuclear basket Nups (Figure 2A). About one-fourth of Nup proteins possess FG dipeptide repeats within intrinsically disordered domains that are enriched for polar amino acid residues and depleted of charged residues (28). The central channel of the NPC, ∼42 nm in diameter in human cells, is lined with FG repeat Nups that restrict the passive diffusion of proteins greater than ∼40 kDa (29).

Nuclear pore complex organization and CA-interacting components. (A) Cartoon depiction of the nuclear pore complex. Structural elements were derived from entry 3103 in the Electron Microscopy Data Bank (EMDB) and PDB entries 5a9q and 5ijn in the Protein Data Bank (PDB). The diagram depicts the nuclear pore complex as a vertical cross-section through the 8-fold symmetric architecture, revealing Y-complex Nups and several inner ring Nups. The locations of cytoplasmic filament Nups and nuclear basket Nups were approximated manually. POMs are not depicted. The identities of individual nucleoporins that are depicted in the cartoon are labeled in matching colors and bold-face font. Nups previously shown to facilitate PIC nuclear import and/or interact with HIV-1 CA are labeled in italicized bold-face font. (B, C) Different perspectives of the intact 8-fold symmetrical nuclear pore. (B) Top-view and (C) view tilted 40° from the top clearly highlight the overall toroidal architecture of the complex.

A variety of mechanisms have been characterized to facilitate the nuclear import of large cytoplasmic cargos. Classically, soluble β- or α-karyopherin nuclear transport factors engage cargo proteins through modular nuclear localization signals (NLSs). In some cases, the NLS-containing cargo first binds an α-karyopherin adapter protein before complexing with a β-karyopherin partner, whereas in other cases the β-karyopherin engages the NLS-cargo protein directly [reviewed in (26)]. The β-karyopherin component of the complex then docks to the NPC to effect nuclear translocation [see (30) for review]. Some proteins, such as transcription factor SPL1, by contrast can gain access to the NPC through direct binding to Nup proteins, in this case via Nup62 and Nup153 (31).

HIV-1 PIC nuclear import

Initial HIV-1 nuclear import studies took reductionist approaches guided by the classical view of nucleocytoplasmic transport to analyze karyophilic properties of individual PIC components. The reasoning was that if proteins in isolation were karyophilic and possessed bona fide NLSs, these would function in the PIC to affect HIV-1 nuclear import. Although such approaches revealed that matrix (32), IN (33,34), and viral protein R (35) were indeed karyophilic, the relevance of these findings to PIC nuclear import proved difficult to reproduce in independent studies (36–40). A 99 nt overlap in the mid-region of the vDNA plus-strand, termed the central DNA flap, was also proposed to mediate PIC nuclear import (41). Although follow-up work discounted a major role for the flap (39,42,43), it can modestly influence the kinetics of nuclear vDNA accumulation (40,44,45). The defining experiment in the field of HIV-1 nuclear import came from studying chimeric viruses between HIV-1 and Moloney murine leukemia virus (MLV), a gammaretrovirus that unlike HIV-1 is unable to infect growth-arrested cells. These data clarified that CA is the determinant required for HIV-1 to productively infect non-dividing cells (46). Because HIV-1 gains nuclear access similarly in cycling and growth-arrested cells (47), results derived from growth-arrested cells pertain to interphase cells as well.

CA is composed of two alpha-helical domains, the N-terminal domain (NTD) and C-terminal domain (CTD), which are separated by a flexible linker (5). Intermolecular NTD-NTD and CTD-NTD interactions juxtapose CA molecules into ringlike hexameric and pentameric capsomers (Figure 3A) (48,49). Higher-order CTD-CTD interactions among adjoining capsomeres template the canonical honeycomb pattern formation within the assembled conical capsid shell (Figure 3B) (1,2,50,51).

HIV-1 capsomeres and the capsid lattice. (A) The capsid lattice is comprised of exactly 12 CA pentamers and ∼200 hexamers, which are shown in top and side views. In both capsomeres the CA CTD is shown in dark blue. While the CA NTD within the hexamer is light blue, it is shown in orange within the pentamer. In each capsomere, a single CA subunit is depicted as a ribbon diagram with matched coloring scheme. (B) An all-atom model of the assembled capsid shell derived from PDB entry 3j3y using the color scheme defined in panel A.

CA was shown recently to bind the β-karyopherin transportin 1 (TRN-1) (52) and can also interact with NPC proteins Nup62, Nup88, Nup98, Nup153, Nup214, and Nup358 (Figure 2) (20,53–56). Other CA-binding proteins that can affect HIV-1 PIC nuclear import include cyclophilin A (CypA) (57,58) and cleavage and polyadenylation specificity factor 6 (CPSF6) (Figure 4A) (59–62).

![Capsid interactions in HIV-1 integration targeting. (A) Organization of principle CA-binding proteins including CypA, Nup358, Nup153 and CPSF6. Locations of CA-binding portions of Nup358, Nup153 and CPSF6 are colored as in subsequent panels. Domain labels are as follows: LRR – leucine-rich region; roman numerals I-IV – Ran binding domains I–IV; ZF – zinc finger; E3 – E3 ligase domain; CHD – cyclophilin homology domain; NTD – N-terminal domain; FG – phenylalanine/glycine repeat domain; RRM – RNA recognition motif; PRD – proline-rich domain; RSLD – arginine/serine-like domain. (B) Interactions of Cyp-like protein domains with the CA NTD. CypA and the C-terminus CHD of Nup358 both interact with the conserved CypA-binding loop, one of two principle binding sites within HIV-1 capsomeres. The CypA and Nup358 structures were derived from PDB entries 1ak4 and 4lqw, respectively. Secondary structural elements of CA are noted on the leftward image. (C) Structures of hexameric capsomeres with peptides derived from Nup153 (top) and CPSF6 (bottom) from PDB entries 4u0c and 4wym, respectively. These peptides lie in a pocket formed between two individual CA subunits. The binding orientations of the respective peptides are non-identical, highlighting the promiscuity of this binding pocket for mediating CA-host factor interactions. (D) Detailed superposition of Nup153 and CPSF6 peptides in complex with CA. Nup153-bound CA molecules are shown in blue while the CPSF6 CA pair is shown in red. For both pairs of CA molecules, individual monomers are differentiated by light and dark coloring. The interaction of each host factor with respective background CAs (light coloring) is anchored by a phenylalanine residue [F284 in CPSF6 (isoform 1 numbering scheme) and F1417 in Nup153]. Docking of this phenylalanine facilitates main chain hydrogen bonding of each host factor with CA residue N57. N74 in CA by contrast preferentially interacts with CPSF6 (green sticks) and not Nup153 (orange sticks). The most pronounced differences in binding modes are derived from interactions with the foreground (darker) CA monomer. CPSF6 adopts a nearly cyclic conformation and interacts primarily with the CTD of the second monomer. In contrast, Nup153 is more linear and interacts with the NTD of the foreground CA subunit.](/dataresources/secured/content-1765824654370-384f382c-a329-4c3c-be55-1a6e1c26ea50/assets/gkaa1207fig4.jpg)

Capsid interactions in HIV-1 integration targeting. (A) Organization of principle CA-binding proteins including CypA, Nup358, Nup153 and CPSF6. Locations of CA-binding portions of Nup358, Nup153 and CPSF6 are colored as in subsequent panels. Domain labels are as follows: LRR – leucine-rich region; roman numerals I-IV – Ran binding domains I–IV; ZF – zinc finger; E3 – E3 ligase domain; CHD – cyclophilin homology domain; NTD – N-terminal domain; FG – phenylalanine/glycine repeat domain; RRM – RNA recognition motif; PRD – proline-rich domain; RSLD – arginine/serine-like domain. (B) Interactions of Cyp-like protein domains with the CA NTD. CypA and the C-terminus CHD of Nup358 both interact with the conserved CypA-binding loop, one of two principle binding sites within HIV-1 capsomeres. The CypA and Nup358 structures were derived from PDB entries 1ak4 and 4lqw, respectively. Secondary structural elements of CA are noted on the leftward image. (C) Structures of hexameric capsomeres with peptides derived from Nup153 (top) and CPSF6 (bottom) from PDB entries 4u0c and 4wym, respectively. These peptides lie in a pocket formed between two individual CA subunits. The binding orientations of the respective peptides are non-identical, highlighting the promiscuity of this binding pocket for mediating CA-host factor interactions. (D) Detailed superposition of Nup153 and CPSF6 peptides in complex with CA. Nup153-bound CA molecules are shown in blue while the CPSF6 CA pair is shown in red. For both pairs of CA molecules, individual monomers are differentiated by light and dark coloring. The interaction of each host factor with respective background CAs (light coloring) is anchored by a phenylalanine residue [F284 in CPSF6 (isoform 1 numbering scheme) and F1417 in Nup153]. Docking of this phenylalanine facilitates main chain hydrogen bonding of each host factor with CA residue N57. N74 in CA by contrast preferentially interacts with CPSF6 (green sticks) and not Nup153 (orange sticks). The most pronounced differences in binding modes are derived from interactions with the foreground (darker) CA monomer. CPSF6 adopts a nearly cyclic conformation and interacts primarily with the CTD of the second monomer. In contrast, Nup153 is more linear and interacts with the NTD of the foreground CA subunit.

Host factors engage CA via two common binding regions. One is the CypA-binding loop, which links alpha helices 4 and 5 within the NTD (Figure 4B) (63). Nup358, which is a cytoplasmic filament Nup, contains a C-terminal cyclophilin-homology domain (CHD) that likewise engages the CypA binding loop (Figure 4B) (19,20,64). Biochemical, genetic and molecular modeling experiments suggest that TRN-1 also engages CA via the CypA binding loop (52) though, unlike CypA and the Nup358 CHD, a CA-TRN-1 complex structure has not been solved using wet-bench approaches such as X-ray crystallography. The second region within CA, a pocket that is primarily formed by NTD alpha helices 3–5 with contributions from a neighboring CA within the hexamer, is where Nup153 and CPSF6 bind (Figure 4C) (54,55,65–67). The FG repeat and central proline-rich domains of Nup153 and CPSF6, respectively, confer binding to CA (54,65). Due to the intrinsically disordered nature of these protein domains, host-CA structures to date have been restricted to Nup153- and CPSF6-derived peptides (55,65–67). For both proteins, a phenylalanine residue of an FG dipeptide occupies the binding pocket, with additional interactions made with the adjoining CA (Figure 4D). Both peptides accordingly bound hexameric capsomeres ∼10-fold more efficiently than the isolated NTD (66). Although Nup62, Nup88, Nup98 and Nup214 in cell extracts co-pelleted with nanotubes assembled from recombinant CA or CA-NC proteins in vitro (53,55,56), direct interactions with CA, as demonstrated through the use of purified Nup proteins or peptides, have not in these cases been confirmed.

The shedding of CA from the core/RTC defines the process of uncoating. Though initially thought to occur soon after virus entry [see (68) for a review], recent evidence suggests that the PIC structurally resembles the intact or nearly intact core during nuclear import (62,69,70). Uncoating (62,69) and the termination of reverse transcription (18,62,69,71,72) are accordingly now thought to occur after nuclear entry. The following scenario can be envisaged for HIV-1 nuclear import. The CA-Nup358 interaction initially docks the PIC to the NPC (20,73,74). One potential role for CypA in nuclear import could be regulation of the CA-Nup358 interaction. Because the CHD has been shown to be dispensable for HIV-1 infection, it seems possible the PIC could also engage one or several of the FG repeats present throughout Nup358 (75). Although cytoplasmic filament Nup214 can co-sediment with CA-NC in vitro (55), its role in HIV-1 infection has been mapped to the post-integration step of mRNA nuclear export (73). After docking, the PIC is shuttled through the NPC in a process possibly involving TRN-1 and/or additional FG repeat Nups such as Nup62 and Nup153. Because the diameter of the wide end of the conical core is ∼60 nm (51,76), it is unclear how an intact or nearly intact core could pass through. We envision that structural flexibility, possibly imparted from both within the viral complex [e.g. vDNA plus-strand discontinuities (77) that enable remodeling (78)] and external to the core [e.g. dynamic nature of the NPC (79,80)], work together to directionally ‘massage’ the oversized cargo. Eventually, the core docks on the nuclear side of the NPC at the nuclear basket via the CA-Nup153 interaction (54,55,67). Recent evidence has suggested that CPSF6 displaces Nup153 from the capsid lattice by competing for the same binding pocket and frees the HIV-1 PIC from the NPC to further its journey into the nucleus (Figure 1) (61).

Because changes in CA residues can dramatically alter HIV-1’s dependency on specific nuclear import factors, it seems that alternative nuclear import pathways must exist for the PIC (59,72). Although the dominant viral determinant for HIV-1 nuclear import is CA (39,46), IN has continued to garner significant focus (81–86) and IN-host interactions could in theory predominate if alternative import pathways are less reliant on CA interactors. IN can interact with numerous soluble transport receptors including α-karyopherin KPNA2/β-karyopherin KPNB1, α-karyopherin KPNA4, TRN-1 and β-karyopherin transportin 3 (TRN-SR2/TNPO3) [reviewed in (87)], as well as NPC components Nup62 (88) and Nup153 (89). However, the relevance of several of these interactions, including those with KPNA4 (86), TNPO3 (90–92), and Nup153 (53,54), have been brought into question. Although HIV-1 infection is significantly reduced via TNPO3 depletion (19,83,90,93,94), this appears to be an indirect consequence of restriction of virus infection due to enhanced cytoplasmic CPSF6 accumulation (59,92,95–97). Comparatively weak, ∼0.1 mM, small molecule inhibitors of IN-TNPO3 (98) and IN-KPNA2/KPNB1 (99) interactions have been reported. Inhibitors with minimally 10-fold increases in potency together with the selection of drug resistance that maps to IN should be accomplished to convincingly demonstrate a pharmacological role for IN in HIV-1 PIC nuclear import. For comparison, low μM to sub-nM HIV-1 inhibitors that bind the CA Nup153/CPSF6 binding pocket displace these proteins and, as part of their multimodal mechanisms of action, inhibit PIC nuclear import (54,55,65,100–102).

HIV-1 integration site targeting

Integration site preferences

Several processes impact the selection of retroviral integration sites in animal cell genomes, with viruses that make up the different genera of Retroviridae displaying largely similar preferences for functional elements such as genes and promoter regions [reviewed in (103)]. High-resolution mapping studies demanded genome-wide capabilities, which were enabled in 2001 via the release of the draft human genome (104). The first genome-wide study, conducted by the Bushman laboratory, revealed that HIV-1 integration is highly biased towards gene-dense regions and highly expressed genes (14). HIV-1 integration was subsequently shown to track with histone modifications associated with active chromatin such as H4K16ac, H3K36me3 and H3K4me1, and disfavor repressive heterochromatin markers such as H3K9me3, H3K27me3 and LADs (15,16). Recent results have clarified that HIV-1 integration highly favors SPADs (18), which are genomic DNA regions that physically associate with nuclear speckles (105,106).

Comparisons of genic HIV-1 integration frequencies across studies revealed the presence of recurrent integration genes or RIGs, which by definition were genes targeted for integration in two or more studies (16,25). RIGs can also be tabulated as genes that are experimentally targeted more frequently than expected based on random chance (17). Imaging HIV-1 proviruses and RIGs in activated CD4+ T cells revealed association of both with the nuclear periphery, defining a specific nuclear architecture for HIV-1 integration site targeting (16). These results were consistent with an independent study that highlighted HIV-1 targeting of chromatin in the peripheral region of the nucleus in a manner dependent on the nuclear basket Nup protein Tpr (23). While some prior studies supported the notion of preferential localization of PICs and proviruses at the nuclear periphery (107,108), subsequent work has highlighted a more pan-nuclear distribution of HIV-1 PICs and integrated proviruses (17,60,62,109,110). In our hands, the vast majority of RIGs harbored pan-nuclear distributions in both transformed HEK293T and activated primary CD4+ T cells (17,18).

Activation of CD4+ T cells yields gross rearrangements in nuclear architecture including actin network formation (111,112). While pan-nuclear RIG distribution was corroborated in resting CD4+ T cells, activation resulted in RIG relocation closer to the nuclear periphery (25). The implications of this reorganization on integration site targeting are not entirely clear. While comparatively slow reverse transcription kinetics limits the efficiency of resting T cell infection in vitro (113), these cells nevertheless support HIV-1 integration (114,115). Although genic integration targeting frequencies were similar in resting and activated CD4+ T cells infected with HIV-1 in vitro, integration in resting cells occurred in modestly less gene-dense regions of chromosomal DNA (116). The limited number of integration sites recovered from such analyses has precluded detailed RIG analyses (25,116). Scaled-up studies should be performed to ascertain whether RIG usage differs in resting versus activated CD4+ T cells. Because SPADs track with gene-rich chromosomal regions (18), such studies would also critically address SPAD integration targeting as a function of T cell activation.

Super-enhancers (SEs) are genomic regions enriched in enhancers, activating epigenetic marks such as H3K4me1 and H3K27ac, as well as binding regions for certain transcription factors [reviewed in (117)]. Recently, SEs were shown to correlate with RIGs, though not with bulk HIV-1 integration sites (18,25). Because SEs are enriched in SPADs (105), the observed correlations between integration sites and SPADs/SEs are likely convoluted. Additional work is required to clarify the contributions of these overlapping genomic markers as predictors of bulk versus RIG-specific HIV-1 integration targeting frequencies.

IN-binding host factors and HIV-1 integration site targeting

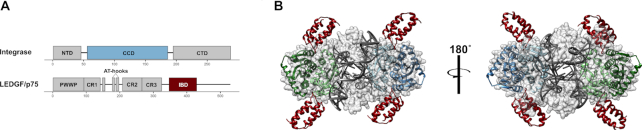

Initial observations that viruses from different retroviral genera displayed dramatically different preferences for promoters versus gene bodies (118,119) indicated that genera-specific host factors could play a role in integration site targeting (120). Indeed, the first cell protein shown to play a significant role in retroviral integration site targeting (121), lens epithelium-derived growth factor (LEDGF)/p75, specifically binds the IN proteins of lentiviruses (Figure 5) (122–124). LEDGF/p75 is a transcriptional co-activator that harbors two conserved domains, an N-terminal Pro-Trp-Trp-Pro (PWWP) domain important for chromatin binding (125–127) and a downstream IN-binding domain (IBD) that is necessary and sufficient to bind HIV-1 IN (128) (Figure 5A and B). LEDGF/p75 significantly stimulated lentiviral IN catalytic activities in vitro (124,126,128–131) and tethered ectopically-expressed HIV-1 IN to cellular chromatin (132). The LEDGF/p75 PWWP domain can engage the trimethylated H3K36me3 modification on nucleosomes assembled in vitro (133–135) and LEDGF/p75 binding sites in cells correlate with H3K36me2 and H3K36me3 marks (136,137). Through its IBD, LEDGF/p75 tethers several different cellular proteins to chromatin to effect transcriptional programming and leukemogenic transformation (138–140).

The integrase-LEDGF/p75 interaction. (A) Domain organization of HIV-1 IN and LEDGF/p75. Domain annotations are as follows: NTD – N-terminal domain; CCD – catalytic core domain; CTD – C-terminal domain; PWWP – Pro-Trp-Trp-Pro domain; CR – charged region; AT-hooks – adenosine/thymine DNA binding motif; IBD – integrase binding domain. The key interacting domains, the IN CCD and LEDGF/p75 IBD, are colored blue and dark red, respectively. (B) Depiction of the core tetramer of the HIV-1 strand transfer complex intasome (PDB 5u1c) bound by the LEDGF/p75 IBD, which was created by superimposing the CCDs of the IBD–HIV-1 IN CCD structure (PDB 2b4j) with the CCDs of the strand transfer complex. Because LEDGF/p75 interacts with integrase at the interface between two CCD dimers, a single intasome contains multiple potential LEDGF/p75 binding sites. Whether all or just a fraction of bound LEDGF/p75 molecules participates in HIV-1/lentiviral integration targeting is not presently known. The IBD color in panel B matches panel A; one of the two CCD dimers in B also matches the panel A coloring.

Efficient knockdown of LEDGF/p75 by RNA interference yielded at best marginal changes in HIV-1 integration site targeting (24,121). By contrast, genic HIV-1 integration targeting was reduced significantly by knocking out PSIP1, the gene that encodes for LEDGF/p75 (141–143). Thus, the normal cellular complement of LEDGF/p75 apparently exceeds by several fold that required by HIV-1 for efficient integration site targeting. LEDGF/p75 is a member of the hepatoma-derived growth factor (HDGF) family, of which one other member, HDGF like protein 2 (HDGFL2), contains an IBD that is homologous to the LEDGF/p75 IBD (128,144). Unlike LEDGF/p75, HDGFL2 at steady-state is found in the nucleoplasm as compared to chromatin-associated (144), which may account for why HDGFL2 appeared to play little if any role in HIV-1 integration site targeting in cells that express LEDGF/p75. A subsidiary role for HDGFL2 in integration site targeting was observed in cells that lacked LEDGF/p75 (145,146).

LEDGF/p75’s tell-tale signature in HIV-1 integration targeting came from analyzing genic integration site distributions across all targeted genes. This analysis first revealed that while MLV integration preferred promoter regions, HIV-1 favored the interior regions of gene bodies (118). HIV-1’s genic integration targeting preference shifted toward gene 5′ end regions in the absence of LEDGF/p75 (24,147). LEDGF/p75 can interact with numerous mRNA splicing factors (136,147) and overcome the transcriptional block imposed by nucleosomes in vitro (137). Thus, current models predict that LEDGF/p75’s function in HIV-1 integration site targeting is determined through interactions with cellular mRNA splicing and/or transcriptional elongation machineries.

Although >200 cellular proteins have been reported to interact with HIV-1 IN [reviewed in (103)], we are unaware of studies that directly implicate any of these beyond LEDGF/p75 and HDGFL2 in HIV-1 integration site targeting. IN-binding factors that seemingly could play such a role include IN interactor 1 (INI1)/SMARCB1 (148), which is a component of BAF and PBAF chromatin remodeling complexes [reviewed in (149)], as well as the histone acetyltransferase enzyme EP300 (150). Additional work is required to ascertain whether these or other IN-binding factors beyond LEDGF/p75 and HDGFL2 play a role in HIV-1 integration site targeting.

CA interactors and HIV-1 integration site targeting

Initial glimpses of CA-binding partner functionalities in HIV-1 integration site targeting indicated these may fundamentally differ from LEDGF/p75. Cellular depletion of TNPO3 or Nup358, but not LEDGF/p75, yielded significant reductions in the number of genes per Mb (gene density) that surrounded HIV-1 integration sites (19). Because an HIV/MLV chimeric virus carrying the MLV gag gene, which among other things encodes for CA, yielded the same result, Ocweija et al. concluded that HIV-1 Gag proteins interact with TNPO3 and Nup358 to target integration to gene-rich chromosomal regions (19). Although as discussed above we now believe that the result with TNPO3 was indirect due to dysregulated CPSF6 localization, preferential disruption of integration into gene enriched regions was observed subsequently in cells depleted for Nup153 (151) or CPSF6 (24). CA mutant viruses with single amino acid changes that disrupt binding to CPSF6, including N74D (20,24,55,59,151) and A77V (152), phenocopied CPSF6 depletion and shifted integration from gene-rich chromosomal regions to gene-sparse regions. Contrastingly, CA changes G89V or P90A, which disrupt the CA-CypA interaction (153,154), retargeted HIV-1 integration to regions marginally more enriched in genes than those targeted by the wild type virus (20).

Results obtained via imaging virus-infected cells have greatly informed the role of CPSF6 in HIV-1 integration site targeting. Depletion of CPSF6 or infection with binding-defective viruses such as N74D and A77V CA mutants resulted in PIC and proviral accumulation in the peripheral region of the nucleus (17,60–62,110,155,156). Concurrent genomic DNA analyses revealed significant upticks in LAD-proximal integration site targeting with parallel reductions in integrations into SPADs (17,18,157). HIV-1 PICs and CPSF6 were accordingly seen to colocalize with nuclear speckles in a variety of acutely-infected cell types including primary CD4+ T cells and macrophages (18).

CPSF6 functions as part of the cleavage factor I mammalian (CFIm) complex, which is one of many complexes that compose the cleavage and polyadenylation complex that processes mRNA 3′ ends for polyadenylation [reviewed in (158)]. CFIm is composed of a heterotetramer of CPSF5 and one of two homologues, CPSF6 or CPSF7 (159). CPSF6 harbors three domains, an N-terminal RNA recognition motif (RRM) that mediates the interaction with CPSF5 (160), a central proline-rich domain that mediates binding to HIV-1 CA (65,161), and a C-terminal arginine/serine-like domain (RSLD) that is enriched in R(D/E) dipeptides and mediates TNPO3 binding (92,97) (Figure 4A). It is somewhat unclear whether CPSF6 function in PIC nuclear import and integration site targeting occurs in the context of CFIm. The vast majority of cellular CPSF6 is sequestered in CFIm (162) and CPSF6- but not CPSF7-containing CFIm colocalized with nuclear PICs (61). However, expression of a CPSF6 RRM deletion mutant defective for CPSF5 binding (163) efficiently restored integration site targeting to CPSF6 knockout cells (162). These data suggest that CPSF6 need not be complexed with CPSF5 to effect PIC nuclear trafficking to speckles for integration into SPADs. As the CPSF6 RSLD was recently shown to play a role in nuclear speckle condensation (164), we suspect that it largely underlies CPSF6-dependent directional PIC trafficking to nuclear speckles (18).

Analyses of cells knocked out for LEDGF/p75 and/or CPSF6 expression have helped clarify the role of each of these factors in HIV-1 integration site targeting. Because the shift in genic integration site distribution to gene 5′ end regions observed in PSIP1 knockout cells was retained in cells knocked out for both factors but absent from CPSF6 knockout cells, we concluded that LEDGF/p75’s primary function is positional integration targeting into gene mid-regions (24). Conversely, peripheral nuclear accumulation of PICs and proviruses with integrations mapping nearby LADs was observed in double knockout as well as CPSF6 knockout cells, indicating that the main CPSF6 role is enabling PIC passage from the periphery into the nuclear lumen to engage nuclear speckles for SPAD-proximal integration (Figure 1) (17,18). This model contrasts prior ones that invoked NPC-proximal integration targeting as a function of Nup153, Tpr and LEDGF/p75 (16,23). Zones of transcriptional activity map to the nuclear periphery in association with NPCs as well as the nuclear interior in close association with nuclear speckles (105). Additional work conducted in primary cells of HIV-1 infection including CD4+ T cells and macrophages should help to clarify the roles of different host factors in integration targeting under physiologically relevant conditions.

Given the role of CPSF6 in PIC nuclear import together with peripheral PIC and proviral accumulation in the absence of CA-CPSF6 binding, our model certainly invokes that CPSF6 acts prior to LEDGF/p75 (Figure 1). While chromatin-binding is essential for LEDGF/p75’s role in HIV-1 integration (127,165), it is less clear if CPSF6 directly tethers PICs to chromatin for integration. Recent research that indicates the PIC retains its CA complement post-nuclear import (62,69,70) is consistent with a model whereby CPSF6 remains PIC-associated post nuclear entry to deliver it to nuclear speckles for integration into SPADs (18) (Figure 1).

The roles of other CA-binding proteins such as Nup358, Nup153 and CypA in HIV-1 integration targeting are less clear. The fact that the Nup358 CHD and CypA share the same binding region on CA (Figure 4B) yet invoke opposite effects on integration into gene-dense regions upon disruption of these virus-host interactions sheds little insight. Possibly, loss of CypA enhances integration into gene-dense chromosomal regions via enhancing the CPSF6-CA interaction and/or slowing the rate of nuclear PIC uncoating. Indeed, CypA was recently shown to block HIV restriction by the antiviral factor TRIM5α by impeding its interaction with capsid (166). It is possible that this same effect is at-play for other host factors involved in HIV-1 biology. CypA was also recently shown to make novel contacts with two additional hexamers in the assembled capsid honeycomb, though the physiological relevance of these findings is not clear (167). Given the breadth of full-length Nup358 with associated FG repeats, it would not be surprising if novel Nup358-CA interactions await discovery.

Many Nups play important cell biology functions outside of their roles as structural components of the NPC [reviewed in (168)]. For example, Y-complex Nup components ELYS and Sec13 (Figure 2) can alter chromatin functionality via interacting with chromatin remodeling complexes (169). Nup153 was recently shown to effect chromatin organization via interacting with architectural proteins CTCF (CCCTC-binding factor) and cohesion (170). Given that Nup153 and CPSF6 share the same binding pocket on CA (Figure 4C and D), additional work is required to discern whether regulating the CA-CPSF6 interaction or perhaps a novel pathway involving CTCF/cohesion underlies Nup153’s role in HIV-1 integration site targeting.

Nucleosomes and tDNA flexibility in integration targeting

Early biochemical studies demonstrated that HIV-1 integration in vitro preferentially occurred in the exposed major groove of nucleosomal DNA (171,172). Subsequent work revealed that a direct interaction between HIV-1 IN and the tail region of histone H4 stimulated integration into nucleosomal DNA in vitro (173,174). Interestingly, DNA minicircles in large part recapitulated the stimulatory effect of tDNA distortion on HIV-1 integration in vitro in the absence of bound protein factors (175).

Studies of prototype foamy virus (PFV) intasomes greatly informed the structural basis of tDNA distortion in retroviral integration. To accommodate scissile phosphodiester bonds that are separated by 4 bp into two IN active sites within the intasome, the tDNA major groove had to distort significantly, to 26.3 Å, with concomitant minor groove compression to 9.6 Å (176). Pyrimidine-purine (YR) dinucleotides, which are inherently flexible, are accordingly naturally selected at the center of the tDNA cut made by PFV IN in cells and in vitro (176). Site-directed mutagenesis revealed roles for PFV IN residues Ala188 and Arg329 in dictating nucleobase selection at integration sites (176). Intasome models based on the PFV structures implicated similar roles for HIV-1 IN residues Ser119 and Arg231 (21,22). Statistical analysis of tDNA sequence preferences of HIV-1 integration revealed weak but significant bias towards the consensus sequence RYXRY, which, akin to PFV, enforces YR at the two dinucleotides that span the center of the 5 bp sequence (22). Interestingly, in addition to altering tDNA bases at integration sites, certain Ser119 and Arg231 substitutions marginally shifted sites of HIV-1 integration to gene-sparse genomic regions (21). Because not all Ser119 and Arg231 substituents conveyed this phenotype, the mechanistic basis for global integration retargeting in these cases is unclear.

Genomic features of active versus latent infection

The vast majority of cells that become infected with HIV-1 support active transcription and the production of new viral progeny (177,178). The advent of combinatorial antiretroviral therapy (ART) enabled acute measures of viral and infected cell dynamics, which revealed that infected cells persist with a half-life of ∼1–2 days due to either virus-induced cell death or immune system eradication (177–181). ART treatment also helped to unveil a latent population of HIV-1 proviruses in patient-derived samples (182–185) that is established early during the course of infection (186,187). Today, it is widely recognized that this population of reactivatable proviruses is the principle barrier to curative HIV-1 strategies (177,178,188,189).

The precise mechanism responsible for the establishment of latent infection is not clear. HIV-1 primarily infects activated CD4+ T cells, but, as previously mentioned, can infect resting CD4+ T cells in vitro. The latent reservoir is most probably established by infection of activated CD4+ T cells that then transition to a resting (memory) state (187,190,191). Interestingly, the vast majority (estimated to be ≥98% in some studies) of integrated proviruses in patient cells are defective due to deletions or hypermutation and thus are incapable of supporting virus replication (189,192–194). These defective proviruses accumulate rapidly during the acute phase of infection (194). A significant fraction of persistently infected cells in patients have moreover been shown to clonally expand (192,195,196). Clonal expansion of infected cells closely parallels seeding of the latent reservoir and tends to increase with time (192,197). Because the majority of the proviruses in these cells are defective, it was initially thought that viral recrudescence upon ART cessation was due to non-clonally expanded but quiescent CD4+ T cells that harbor intact provirus (192). However, subsequent studies have shown that sufficient intact proviruses exist in the clonally expanded population to support the resurgence of viral replication (193,198–200).

Like integration site preferences in vitro, the majority of integrations in chronically infected patients are observed in genes (192,195,196). Repressive chromatin marks such as H3K9me3, H3K27me3 and CpG methylation have been linked to the establishment of latency (201–206). Interference of HIV-1 transcription caused by active host gene expression and provirus orientation have been proposed to modulate latency (207–209). Components of the mTOR complex and related downstream factors have also been shown to influence latency, possibly through modulating TCR/CD28 signaling and/or NF-κB activation (210). These observations are consistent with the notion that suppression of viral transcription is a key component of HIV-1 latency. The use of barcoded viruses to track individual integration sites has accordingly indicated that latent proviruses are more distal from activating epigenetic marks than are expressed viruses (206,211). Recently, proviruses from elite controllers, which represent a minority of patients that control their infection in the absence of ART, were shown to adopt a state of ‘deep latency’ due to integration into heterochromatic regions such as centromeric satellite DNA and Krüppel-associated box domain-containing zinc finger genes (212).

Subsets of genic HIV-1 proviruses have been linked to persistence and clonal expansion of infected cells in patients on long-term ART (195,196,213,214). Integration into specific regions of MKL2, BACH2 and STAT5B, for instance, are highly enriched in patient samples (192,195,196). Interestingly, these genes are linked to tumorigenesis, T cell homeostasis, B cell development, and/or immune signaling (215–220). It has been hypothesized that these innate biological functions underlie their overrepresentation in persistent/clonally expanded infected T cell populations (195). Consistent with this hypothesis, it has been shown that many (but not all) integrations into BACH2 and STAT5B result in splicing-induced fusion of viral sequences to the first protein coding exon of these genes (221) – a mechanism conceptually similar to the fusion proteins found in many cancers (222). These fusions can increase the proliferation and survival of T regulatory cells without imparting deleterious effects on their function (221).

CONCLUSIONS

We have witnessed significant progress in understanding the intricacies of HIV-1 integration site targeting over the past two decades. Animal cell genomic sequences have enabled the mapping of individual retroviral integration sites on massive scales. Intasome studies have informed the structural bases of nucleobase selection at sites of vDNA joining. Advances in cell biology have enabled rapid, targeted ablation of specific cell factors by RNA interference and knockout strategies such as CRISPR-Cas9, greatly accelerating the pace of research. Such approaches are crucial to inform the roles of virus-host interactions in HIV-1 integration targeting. Disruption of HIV-host interactions important for integration site targeting has importantly informed novel antiviral inhibitor development. Small molecule inhibitors of CA-Nup153/CPSF6 (102) and IN-LEDGF/p75 [reviewed in reference (87)] interactions engage multiple copies of their respective viral targets, eliciting multipronged allosteric antiviral responses.

Roles for integration sites in establishing and regulating latency are beginning to emerge. Fundamental questions remain, however. From the perspective of a cure, one of the most pressing questions is the relationship between integration site and proviral transcription. Although chromatin landscape around HIV-1 integration sites can influence viral gene expression (206,211), how this relates to latency and cellular persistence/clonal expansion in patients is not explicitly known. Additional research on understanding the reasons why particular integration sites are enriched in clonally expanded and persistent cells in vivo is surely warranted. Plausibly, this could inform the development of novel therapeutics to eradicate viral recrudescence that otherwise widely pervades ART cessation. The observation that a small fraction of patients seemingly self-cure via the elimination of cells that otherwise could reseed virus replication indicates that an immunological approach to HIV cure may be plausible (212).

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Authors contributions: G.J.B. and A.N.E. wrote the paper.

FUNDING

US National Institutes of Health [R37AI039394, R01AI052014 to A.N.E., T32AI007386 to G.J.B.]. The open access publication charge for this paper has been waived by Oxford University Press – NAR Editorial Board members are entitled to one free paper per year in recognition of their work on behalf of the journal

Conflict of interest statement. A.N.E. has received fees from ViiV Healthcare Co. over the past 12 months for work unrelated to this study.

REFERENCES

1.

2.

4.

5.

6.

7.

8.

9.

10.

11.

12.

13.

14.

15.

16.

17.

18.

19.

20.

21.

22.

23.

24.

25.

26.

27.

28.

29.

30.

31.

32.

33.

34.

35.

36.

37.

38.

39.

40.

41.

42.

43.

44.

45.

46.

47.

48.

49.

50.

51.

52.

53.

54.

55.

56.

57.

58.

59.

60.

61.

62.

63.

64.

65.

66.

67.

68.

69.

70.

71.

72.

73.

74.

75.

76.

77.

78.

79.

80.

81.

82.

83.

84.

85.

86.

87.

88.

89.

90.

91.

92.

93.

94.

95.

96.

97.

98.

99.

100.

101.

102.

103.

104.

105.

106.

107.

108.

109.

110.

111.

112.

113.

114.

115.

116.

117.

118.

119.

120.

121.

122.

123.

124.

125.

126.

127.

128.

129.

130.

131.

132.

133.

134.

135.

136.

137.

138.

139.

140.

141.

142.

143.

144.

145.

146.

147.

148.

149.

150.

151.

152.

153.

154.

155.

156.

157.

158.

159.

160.

161.

162.

163.

164.

165.

166.

167.

168.

169.

170.

171.

172.

173.

174.

175.

176.

177.

178.

179.

180.

181.

182.

183.

184.

185.

186.

187.

188.

189.

190.

191.

192.

193.

194.

195.

196.

197.

198.

199.

200.

201.

202.

203.

204.

205.

206.

207.

208.

209.

210.

211.

212.

213.

214.

215.

216.

217.

218.

219.

220.

221.

Factors that mold the nuclear landscape of HIV-1 integration

Factors that mold the nuclear landscape of HIV-1 integration