- Altmetric

Discrete time crystals are periodically driven systems characterized by a response with periodicity nT, with T the period of the drive and n > 1. Typically, n is an integer and bounded from above by the dimension of the local (or single particle) Hilbert space, the most prominent example being spin-1/2 systems with n restricted to 2. Here, we show that a clean spin-1/2 system in the presence of long-range interactions and transverse field can sustain a huge variety of different ‘higher-order’ discrete time crystals with integer and, surprisingly, even fractional n > 2. We characterize these (arguably prethermal) non-equilibrium phases of matter thoroughly using a combination of exact diagonalization, semiclassical methods, and spin-wave approximations, which enable us to establish their stability in the presence of competing long- and short-range interactions. Remarkably, these phases emerge in a model with continous driving and time-independent interactions, convenient for experimental implementations with ultracold atoms or trapped ions.

Discrete time crystals are typically characterized by a period doubled response with respect to an external drive. Here, the authors predict the emergence of rich dynamical phases with higher-order and fractional periods in clean spin-1/2 chains with long-range interactions.

Introduction

Due to its foundational and technological relevance, the study of condensed matter systems out of equilibrium has attracted growing interest in recent years, accounting among others for the discovery of dynamical phase transitions1,2, quantum scars3, and, particularly, discrete time crystals (DTCs)4–12. A DTC is a nonequilibrium phase of matter breaking the discrete time translational symmetry of a periodic (i.e., Floquet) drive. In the thermodynamic limit, the defining feature of an n-DTC is a subharmonic response at 1/nth of the drive frequency (n > 1), which is robust to perturbations and which persists up to infinite time12. Following the first seminal proposals4–8, DTCs have been widely investigated both theoretically and experimentally12–23.

In this context, most work has focused on spin-1/2 systems, which have largely been shown to exhibit a 2-DTC where at every Floquet period each spin (approximately) oscillates between the states and

In these systems, heating to a featureless “infinite temperature” state is typically avoided by introducing disorder, which leads to a (Floquet) many-body-localized (MBL) phase5,8. Alternatively, in clean (i.e., non-disordered) systems, heating can be escaped with all-to-all interactions12,25,28, or significantly slowed down with long-range interactions29–32. Very recently, ref. 32 has provided the theoretical framework to study Floquet, clean, long-range interacting systems, in which novel prethermal phases of matter are expected. While their framework allows for the possibility of n-DTCs with n larger than the size of the local (or single-particle) Hilbert space, their concrete examples are limited to n = 2. From our analysis below, we see that part of the difficulty in numerically observing what we call “higher-order” DTCs may lie in their emergence at system sizes that are typically beyond the reach of exact diagonalization.

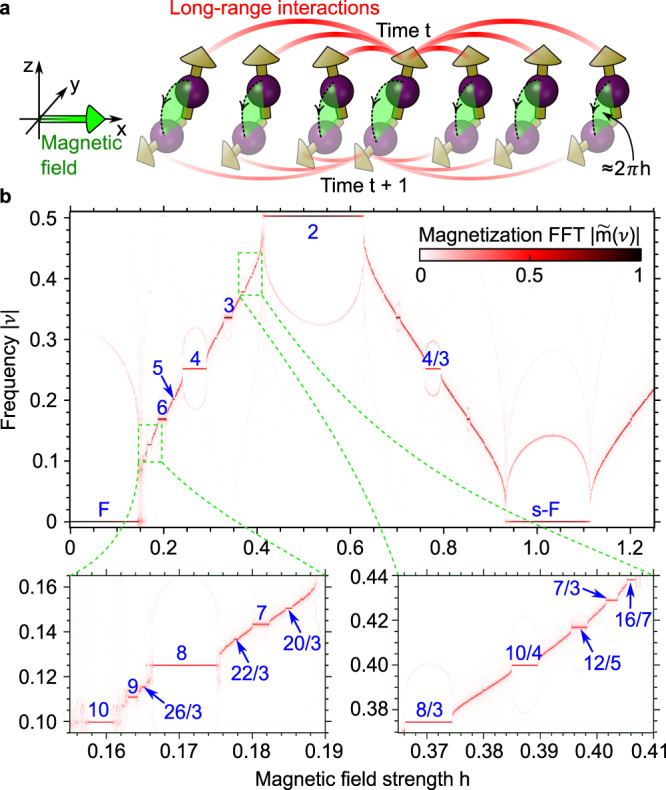

Here, we overcome this limitation by considering a system amenable to a set of complimentary methods, which enable us to discover an unusually rich dynamical phase diagram hosting a zoo of novel, exotic (and arguably prethermal) nonequilibrium phases of matter. More specifically, we show that a clean spin-1/2 chain in the presence of long-range interactions (Fig. 1a) can sustain robust higher-order n-DTCs with integer and, remarkably, even fractional n > 2 (e.g., n = 3, 4, 8/3, and beyond). These novel dynamical phases give rise to a peculiar fragmentation of the magnetization spectrum, which is intriguingly reminiscent of the plateau structure of the fractional quantum Hall effect.

Higher-order and fractional discrete time crystals.

a A spin-1/2 chain with long-range interactions and initial z-polarization is driven with a monochromatic transverse magnetic field of strength h, inducing a spin precession around x. b The time crystallinity is probed by the Fourier transform

In the following, we present a rather general model of long-range interacting spins, thoroughly study its semiclassical (i.e., mean-field) limit, and finally show that the physics observed extends far beyond the fine-tuned limit. We note that our work is distinct from traditional MBL DTCs, which do not have such a semiclassical limit. On a conceptual level, our analysis is closer to that of equilibrium statistical physics, where, for example, the ferromagnetic phase in the Ising model is best understood in a mean-field description, which is exact in the limit of all-to-all interactions. In our out-of-equilibrium and clean setting, the existence of a conceptually simple mean-field limit is particularly valuable, and highlights profound differences between the clean DTCs considered here and the pioneering works on MBL DTCs.

Results

We consider a one-dimensional chain of N spins in the thermodynamic limit (N → ∞), driven according to the following time-periodic Hamiltonian

The dynamics from an initially z-polarized state

For the sake of clarity, we first focus on the LMG limit of all-to-all interactions (α = λ = 0), which allows for a conceptually simple semiclassical interpretation of the various dynamical phases. The dynamics of the system is in this case described by a semiclassical Gross–Pitaevskii equation (GPE) for the complex fields ψ↑ and ψ↓ (details in Supplementary Note 1)

The dynamics of the magnetization m is obtained integrating the GPE (2) from an initially z-polarized state (ψ↑(0) = 1, ψ↓(0) = 0), and the corresponding Fourier transform

The plateau at ν = 0 for h ≈ 0 signals the tendency of the spins to remain aligned along z in a dynamical ferromagnetic phase (F). This corresponds to macroscopic quantum self-trapping of weakly driven bosons in a double well34, which can in fact be exactly mapped to the LMG limit (details in Supplementary Note 1). For h ≈ 1, 2, 3, …, the spins complete approximately 1, 2, 3, … revolutions around the Bloch sphere at each drive period, respectively, and yet maintain a preferential alignment along z at stroboscopic times, in what may be called a stroboscopic-ferromagnetic phase (sF).

Our results are confirmed by exact diagonalization studies. Owing to the all-to-all coupling of the LMG limit, the dynamics is in fact confined to the symmetric sector, whose size grows only linearly with the number of spins N. This allows a scaling analysis extended up to large system sizes, showing a progressive emergence of the spectral line plateaus for an increasing number of spins N. For the standard 2-DTC, the plateau is clearly visible already for N ⪆ 10, whereas, crucially, for the 4-DTC it appears only for N ⪆ 100 (see details in Supplementary Note 2). This observation strongly suggests that signatures of the higher-order n-DTCs arise for larger system sizes as compared to the standard 2-DTC, making them generally elusive to exact diagonalization techniques. This fact might explain the difficulties in observing higher-order DTCs in the past and motivates the choice of model (1) in the first place.

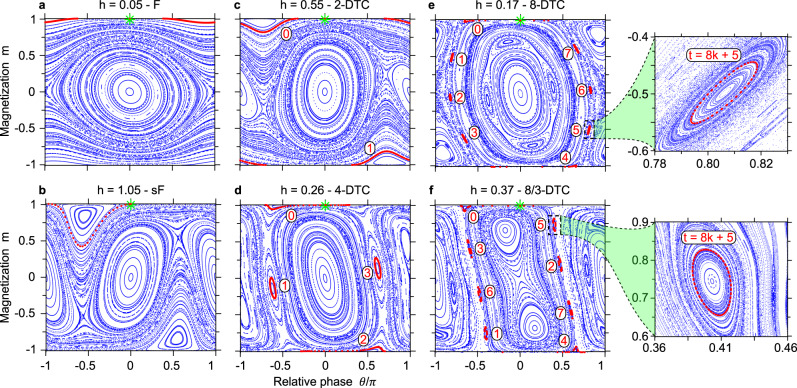

The stroboscopic dynamics generated by the GPE (2) can be conveniently described with Poincaré maps, popular tools in dynamical systems theory that here provide an immediate interpretation of much of the underlying physics, which to some extent characterizes the dynamical phases also when deviating from the LMG limit. In Fig. 2, the trajectory starting in the z-polarized state (green asterisk) is highlighted with red markers. For a weak drive h ≈ 0, the spins tend to remain aligned along z in a dynamical ferromagnetic phase (a), giving rise to a Poincaré map which closely resembles the phase portrait of undriven bosons in a double well34. For h ≈ 1, the micromotion consists of approximately an entire revolution of the spins around the Bloch sphere per period, with a preferential z alignment restored at stroboscopic times despite the detuning in the magnetic field strength (b). For h ≈ 1/n and n = 2, 4, 8 in (c), (d), and (e), respectively, the n-DTC results in the presence of n “islands” in the phase space, which the system visits sequentially jumping from one to the next at each drive period. In n drive periods, the system visits all the n islands once, and the magnetization m completes one oscillation.

Phase space structure of the dynamical phases.

Poincare maps of the semiclassical dynamics (2) for various magnetic field strengths h and a fixed interaction J = 0.5. Red markers highlight the trajectory starting in the z-polarized state (m = 1, θ = 0, green asterisk). a Dynamical ferromagnet (F): the magnetization m remains ≈1 at all times; b stroboscopic ferromagnet (sF): the magnetization m changes sign during the micromotion and yet it remains positive at stroboscopic times; c 2-DTC: the system alternatively visits two islands of the phase space—one with m ≈ 1 (numbered as 0) at even times, and the other with m ≈ − 1 (numbered as 1) at odd times; d, e higher-order n-DTCs with integer n = 4, 8, respectively: the system visits cyclically n islands of the phase space (accordingly numbered in red), with one tour of the islands corresponding to one complete revolution of the spins around the Bloch sphere. f Higher-order n-DTC with fractional n = q/p = 8/3: it takes p revolutions of the spins for the system to tour q islands of the phase space, resulting in a sharp magnetization oscillation frequency ν = p/q. The insets on the right zoom on the island visited at times t = 8k + 5, k = 0, 1, 2, … for the 8-DTC (top) and the 8/3-DTC (bottom).

Furthermore, for h ≈ 3/8 the system behaves as a n-DTC with fractional n = q/p = 8/3 (f). In this case, the system cyclically visits q islands of the phase space in q drive periods. Differently from a q-DTC, however, during this time the magnetization m completes p oscillations, resulting in a characteristic frequency p/q. Finally, for larger interactions J the Poincaré maps become chaotic (as in ref. 12), signaling thermalization35.

Since the island-to-island hopping that underpins the subharmonic response holds for any point of any island, the islands themselves can be interpreted as stability regions of the DTCs with respect to perturbations of the initial state. The Poincaré maps also provide an interpretation of the subdominant frequencies visible as halos around the plateaus in Fig. 1, which are in fact associated with the revolution period of the intra-island orbits (e.g., those shown in the insets of Fig. 2). This also explains why these frequencies are sensitive to perturbations of the drive, which deform the shape of the islands and thus the orbits’ revolution periods, but are only weakly sensitive to perturbations of the initial state.

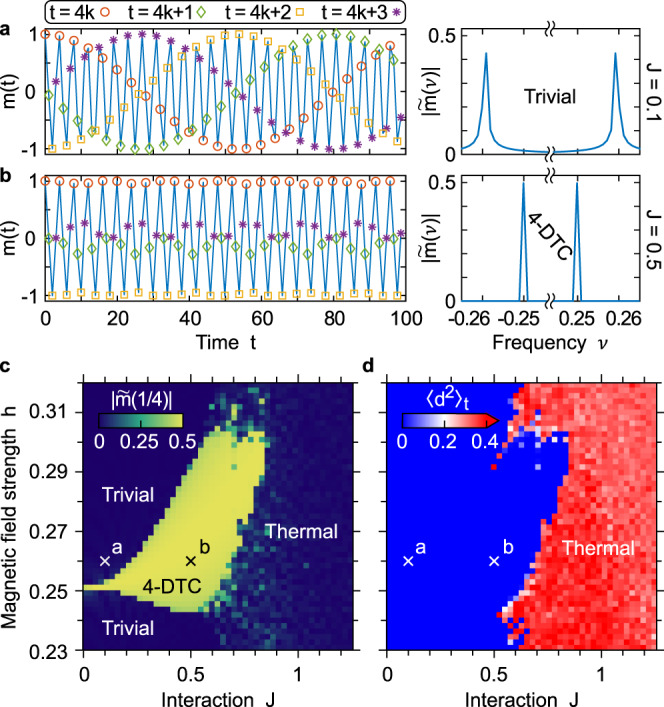

It is well established for the standard 2-DTC that the robust subharmonic response hinges on the interaction being sufficiently strong. The fact that interactions are necessary for the robustness of DTCs is critical, as it underpins the many-body nature of the DTCs and it justifies their classification as nonequilibrium phases of matter10. It becomes thus of primary importance to assess the role of the interactions also for the higher-order DTCs. To this end, as a concrete example, in Fig. 3 we investigate the effects of the interaction strength J on the 4-DTC. If the interaction is weak, a slightly mistaken magnetic field strength h = 1/4 + ϵ, with ϵ ≪ 1, originates in envelopes (i.e., beatings) with period ~1/ϵ, resulting in the Fourier transform

Many-body nature of the higher-order discrete time crystals.

The robustness of the higher-order time crystals is induced by the interactions, justifying their classification as nonequilibrium phases of matter. For concreteness, we show this for the 4-DTC in the LMG limit. a, b Magnetization m(t) at stroboscopic times (left) and respective Fourier transform

The subharmonic peak magnitude

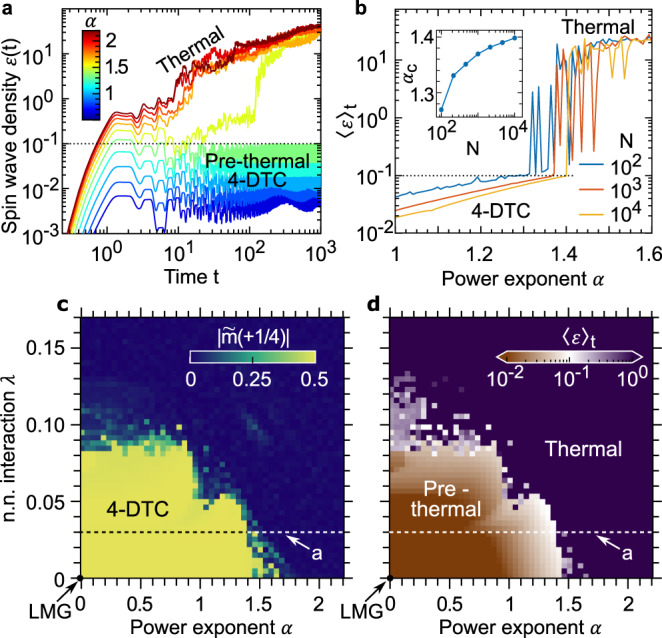

As shown, the DTCs rely on the interactions being sufficiently (but not too) strong. Crucially, in contrast to the standard 2-DTC, higher-order DTCs also necessitate the interactions to be sufficiently long range. We now probe the robustness of the higher-order DTCs along yet a different direction in the drive space, exploring the effects of non-all-to-all interaction on higher-order DTCs, particularly assessing their stability upon breaking the mean-field solvability of the dynamics with power-law (α > 0) and nearest-neighbor (λ > 0) interactions. In this case, the system is no longer described as a collective spin, and spin-wave excitations are rather generated. To account for them, we adopt a spin-wave approximation (see “Methods”), in which the central dynamical variable is the density of spin-wave excitations ϵ(t)

In the LMG limit (λ = α = 0), no spin-wave excitation is generated and ϵ = 0 at all times. When departing from such a limit, two scenarios are possible (Fig. 4a): (i) ϵ rapidly reaches a plateau ⪅ 0.1 (up to some small fluctuations), for which we consider the spin-wave approximation consistent, or (ii) ϵ rapidly grows to values ⪆ 1, for which the spin-wave approximation breaks down. Although the method is not exact and may fail to capture the very long-time physics, it suggests that (i) and (ii) correspond to prethermalization and thermalization, respectively15,36,37.

Stability and prethermalization with power-law and nearest-neighbor interactions.

The higher-order and fractional DTCs survive, most likely in a prethermal fashion, when deviating from the LMG limit. For concreteness, we focus on the 4-DTC at h = 0.27 and J = 0.5, and consider the effects of power-law (α > 0) and nearest-neighbor (λ > 0) interactions. a If the interactions are sufficiently long-range (that is α is small enough, here for a fixed λ = 0.03), the density of spin-wave excitations ϵ remains small throughout several time decades. Conversely, shorter-range interactions lead to the proliferation of spin-wave excitations that makes the system quickly thermalize destroying any time crystalline order15. b A sharp transition between these two regimes is highlighted by the time average 〈ϵ〉t over 103 periods versus α (at a fixed λ = 0.03). The critical αc at which 〈ϵ〉t crosses the threshold 0.1 (inset), grows and possibly saturates with the system size N, suggesting the stability of the 4-DTC in the thermodynamic limit N → ∞. c, d The stability of the 4-DTC for a whole region of the parameter space surrounding the LMG point α = λ = 0 is highlighted plotting the magnitude of the subharmonic peak

We observe that the higher-order DTCs are stable (at least in a prethermal fashion) for sufficiently long-range interactions (i.e., sufficiently small λ and α), whereas thermalization quickly sets in for shorter-range interactions (Fig. 4a). The transition between these two dynamical phases is sharp and can be located comparing the spin-wave density time average 〈ϵ〉t with a threshold 0.1 (Fig. 4b). The stability of the n-DTC in the presence of competing power-law and nearest-neighbor interactions can be investigated in the (α, λ) plane plotting the amplitude of the subharmonic peak

Discussion

Higher-order DTCs in clean long-range interacting systems are qualitatively distinct from DTCs of MBL Floquet systems32. Indeed, the higher-order DTCs require the establishment of order along directions different from ±z. For instance, in the 4-DTC the spins are approximately aligned along −y and +y at times t = 1, 5, … and t = 3, 7, …, respectively. In an MBL system, a disordered magnetic field or short-range interaction along z would immediately scramble the system when the spins are far from the z-axis, precluding the possibility of higher-order DTCs. Thus, our work establishes that translationally invariant systems with long-range interactions can circumvent these limitations14,32.

In the LMG limit of all-to-all interactions, the model (1) has a low-dimensional semiclassical limit, which links the n-DTCs to the multifrequency mode locking of some nonlinear discrete maps, which is ubiquitous in the natural sciences38–41. On the one hand, our work establishes a connection between this class of DCTs and dynamical system theory. On the other hand, it provides evidence for the stability of the higher-order DTCs in a whole region of the parameter space surrounding the LMG limit, in the presence of competing, mean-field breaking, long- and short-range interactions, which is in a genuinely quantum setting with no semiclassical counterpart.

The choice of a continuous Floquet drive with constant-in-time interactions and monochromatic transverse magnetic field, together with the translational invariance, makes model (1) a prime candidate for experimental implementation. For instance, bosons in a double well34 could be used to realize a truly all-to-all interaction, which is the LMG, model. In this case, the field pulses would be simply implemented lowering the barrier between the two wells to allow particle tunneling, and the fact that no time modulation for the particle–particle interaction is necessary should provide a major simplification. Power-law interactions with tunable alpha 0 ≤ α ≤ 3 can instead be realized in trapped-ion experiments17,42,43. For completeness, we note, anyway, that a phenomenology similar to that presented here also emerges in the case of a binary drive (see Supplementary Note 4 for details).

In conclusion, we have discovered higher-order DTCs with a period that is not limited from above by the size of the local (or single-particle) Hilbert space. The dynamical phase space fragments to host many higher-order n-DTCs with integer and even fractional n, at least in a prethermal fashion. Future work should attempt to gain further analytical understanding regarding the role of long-range interactions in stabilizing the different higher-order DTCs. Most importantly, it should be assessed what are the allowed fractions q/p that result in a q/p-DTC? Further study should assess in more detail the role of the Kac normalization and of the dimensionality on the fate of the dynamical phases of matter presented here.

Methods

Decorrelator

We quantify the sensitivity to the initial conditions of Eq. (2) with a decorrelator d2(t)28,44

Spin-wave approximation

Here, we briefly summarize the idea behind the spin-wave approximation, which is thoroughly explained in refs. 36,37 and the Supplementary Material therein, to which we redirect the reader for further details. In a DTC evolving from an initially z-polarized state

Finally, we remark the main differences between the implementation of the spin-wave approximation in our work and in ref. 36. First, ref. 36 considers a constant-in-time Hamiltonian, whereas the parameters of the Hamiltonian in the present work are time-dependent. As a consequence, the parameters in the system of ordinary differential equations become time-dependent. Second, ref. 36 considers a nearest-neighbor interaction on top of an all-to-all one, whereas we consider the more general case of nearest-neighbor interaction on top of a power-law one. The

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41467-021-22583-5.

Acknowledgements

It is a pleasure to thank F. Carollo, E.I.R. Chiacchio, F.M. Gambetta, J.P. Garrahan, and A. Lazarides for useful discussions. A.P. acknowledges support from the Royal Society. A.N. holds a University Research Fellowship from the Royal Society and acknowledges additional support from the Winton Program for the Physics of Sustainability.

Author contributions

A.P. carried out the research, and J.K. and A.N. supervised it. All authors gave critical contributions to the manuscript preparation.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

Code availability

The codes that support the findings of this study are available from the authors on reasonable request.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

References

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

6.

7.

8.

9.

10.

11.

12.

13.

14.

15.

16.

17.

18.

19.

20.

21.

22.

23.

24.

25.

26.

27.

28.

29.

30.

31.

32.

33.

34.

35.

36.

37.

38.

39.

40.

41.

42.

43.

44.

Higher-order and fractional discrete time crystals in clean long-range interacting systems

Higher-order and fractional discrete time crystals in clean long-range interacting systems