- Altmetric

Semiconductor quantum-dot spin qubits are a promising platform for quantum computation, because they are scalable and possess long coherence times. In order to realize this full potential, however, high-fidelity information transfer mechanisms are required for quantum error correction and efficient algorithms. Here, we present evidence of adiabatic quantum-state transfer in a chain of semiconductor quantum-dot electron spins. By adiabatically modifying exchange couplings, we transfer single- and two-spin states between distant electrons in less than 127 ns. We also show that this method can be cascaded for spin-state transfer in long spin chains. Based on simulations, we estimate that the probability to correctly transfer single-spin eigenstates and two-spin singlet states can exceed 0.95 for the experimental parameters studied here. In the future, state and process tomography will be required to verify the transfer of arbitrary single qubit states with a fidelity exceeding the classical bound. Adiabatic quantum-state transfer is robust to noise and pulse-timing errors. This method will be useful for initialization, state distribution, and readout in large spin-qubit arrays for gate-based quantum computing. It also opens up the possibility of universal adiabatic quantum computing in semiconductor quantum-dot spin qubits.

Previous demonstrations of spin state transfer in quantum dot chains relied on physical motion of electrons or sequences of SWAP operations. Here, the authors implement an alternative method based on adiabatic evolution, offering advantages in terms of implementation and robustness to noise and errors.

Introduction

Progress toward fabrication of large spin-qubit arrays1,2, together with methods for orthogonal control of quantum-dot chemical potentials2–4, inter-dot tunnel couplings5–9, and nearest-neighbor exchange couplings10, have opened up the possibilities of implementing complex multi-qubit quantum operations11,12 in semiconductor quantum-dot spin qubits. To tap the full potential of these developments, and to realize a large-scale fault-tolerant quantum computer, high-fidelity information transfer mechanisms between qubits are required. Since quantum-dot spin qubits naturally interact through the nearest-neighbor Heisenberg exchange-coupling, long-distance inter-qubit coupling is challenging. Quantum information transfer has been achieved in spin qubits by electron shuttling using electrical pulses3,13–15, mechanical waves16, spin SWAP operations11,17, and quantum mediators18,19. These methods, elegant as they are, have their limitations, often including stringent pulse-timing requirements. In this work, we report evidence for the successful experimental implementation of adiabatic evolution methods to achieve quantum information transfer in a chain of four quantum-dots. Compared to conventional pulsed information transfer methods, adiabatic techniques are more robust to pulse errors and system noise.

Adiabatic quantum information processing in arrays of spin qubits has been the focus of intense theoretical research20–29, due to the possibility of high-fidelity operations in the presence of noise or pulse errors. Adiabatic shuttling of spin states has been already demonstrated via electron shuttling3,13–15. Here, we present evidence for adiabatic quantum-state transfer (AQT) of both single-spin eigenstates and two-spin singlet states in a GaAs quadruple quantum-dot device. Unlike previous works, this approach does not involve the physical motion of electrons. Specifically, we design a time-dependent Hamiltonian for a linear chain of three electron spins. As the spins evolve under the action of the Hamiltonian, an initial state of the first spin is transferred to the third spin. This process is closely related to stimulated adiabatic Raman passage, a time-honored technique from the optical physics community30, which has been implemented in other qubit platforms30–33. Also, the process we use is identical to adiabatic quantum teleportation21,24. We show that the AQT process can be cascaded to transfer spin states across a longer spin chain.

We simulate our experiments, taking into account known sources of errors and noise (see “Methods”), and we find that the results of our simulations closely match the experimental data. Based on those simulations, we estimate that the probability to correctly transfer a single-spin eigenstate or a two-spin singlet state can exceed 0.95, in operation times of <127 ns. In lieu of full quantum-state tomography, which would require a micromagnet34 or an antenna35 for magnetic resonance, we implement different quantum gates to assess the spin states after AQT. In the future, state and process tomography will be required to verify the AQT performance. The main limiting factor of the AQT fidelity in our experiment is the nuclear hyperfine noise in the GaAs/AlGaAs heterostructure, which gives rise to a fluctuating magnetic-field gradient between dots. In Si devices, we expect that high-fidelity transfer of arbitrary single-qubit states could easily be achieved (see “Methods” and Supplementary Information)24,36.

Results

Device

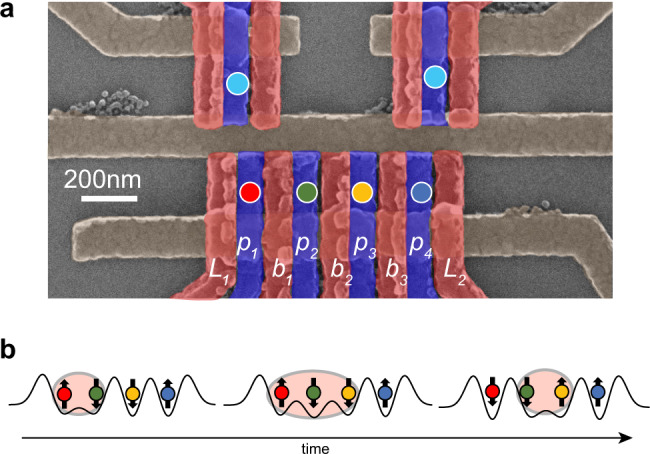

Our quadruple quantum-dot device with overlapping gates is fabricated in a GaAs/AlGaAs heterostructure [Fig. 1a]1,37. Two additional dots above the main array are configured for readout via rf-reflectometry38. We divide the quadruple quantum dot array into two pairs for initialization and measurement. Dots 1 and 2 form the “left” side and dots 3 and 4 form the “right” side. We measure the left and right pairs in the two-electron singlet/triplet basis using Pauli spin blockade together with a shelving mechanism39. The singlet is , and the triplets are

Experimental setup.

a False-color scanning electron micrograph of a quadruple quantum-dot device similar to the one used in the experiment. The quantum dots are located in 2DEG below the positions marked by circles. Voltages applied to three layers of metal gates (brown, red, and blue) create the quantum-dot confinement potentials. A top gate, which is not present in this figure, covers the active area of the device. b Schematic showing the changes in the quantum-dot barrier heights for an AQT process that transfers the state of spin 3 to spin 1. This process also transfers the state of spins 1–2, which are in an eigenstate of exchange, to 2–3.

The linear chain of spins with time-dependent nearest-neighbor exchange couplings in our device can be modeled using the Heisenberg model, and the Hamiltonian is

Adiabatic quantum-state transfer

To implement adiabatic spin-state transfer, we initialize the spin chain in the state

Once the spin chain is initialized, we set [J1(t), J2(t), J3(t)] = Jmax[1 − t/T, t/T, 0] for 0 < t < T, with Jmax = 120 MHz. Note that the initial state discussed above is an eigenstate of H(0) when

![Eigenstates of the time-dependent three-spin Heisenberg Hamiltonian with [J1(t), J2(t)] = Jmax [1 − t/T, t/T] for 0 < t < T.](/dataresources/secured/content-1766052662213-85721333-68de-4037-b410-64ac5bd7d89b/assets/41467_2021_22416_Fig2_HTML.jpg)

Eigenstates of the time-dependent three-spin Heisenberg Hamiltonian with [J1(t), J2(t)] = Jmax [1 − t/T, t/T] for 0 < t < T.

Bz is the uniform magnetic field. The eigenstates at the initial and final times are labeled. Adiabatic state transfer can occur by initializing the system in either the

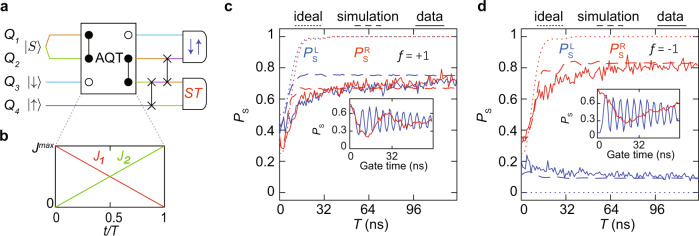

To measure the spin states after the AQT process, we apply SWAP operations11 between spins 3–4 and 2–3, in this order, to bring the singlet state to the right pair and the product state to the left pair of spins before measurement [Fig. 3a]. We measure the left pair by adiabatic projection and the right pair by diabatic projection onto the singlet/triplet basis42,43. Diabatic projection preserves the singlet state, and adiabatic projection maps either

Three-spin AQT.

a Quantum circuit diagram for the experiment. The spin chain is initialized as

Effects of the nuclear hyperfine gradient

Since the initial product state of the left pair is eventually measured in the right pair, knowledge of the magnetic-field gradients in both pairs is required for proper interpretation of the experimental data. We define

Figure 3c, d shows the results of the experiment described by the circuit of Fig. 3a for the f = +1 and f = −1 cases, respectively. Calculated outcomes for the ideal cases, and simulation results taking into account all known sources of noise and errors, are overlaid on top of the data. The simulation results match the measurements in both cases (see “Methods”). In Fig. 3c, d, the gradual rise in the return probability with T occurs because for small values of T, the process is not sufficiently adiabatic. At large values of T, the return probabilities saturate, suggesting successful adiabatic transfer. The predicted oscillations in the return probability at small values of T are related to resonant adiabatic transfer24, which we discuss further below.

Each data point in Fig. 3 is averaged over 512 single-shot measurements for each value of T. We repeat this sequence of 512 single-shot measurements 256 different times. Each repetition takes no more than one second to acquire, and the hyperfine gradients and the value of f are empirically quasi-static during each repetition. Different repetitions were thus used for the f = +1 and f = −1 cases shown in Fig. 3. The full dataset, which includes all repetitions, is shown in Supplementary Fig. 3. We display single repetitions here, because the approximately constant value of the hyperfine field during a single repetition enables accurate simulation.

As discussed further in “Methods”, the sign of f changes on a timescale ranging from seconds to tens of seconds, and typical gradient strengths are on the order tens of MHz. These values are consistent with previous estimates of nuclear spin diffusion times and rates in GaAs double quantum dots44,45.

Coherent evolution after AQT

To further assess the AQT, we use additional quantum gates to test the spin states. First, we transfer the spin states as described above with Jmax = 120 MHz and T = 127 ns. Then, we perform the SWAP gates discussed previously. In the case of successful state transfer, the initial product state of spins 3–4 occupies spins 1–2, and the initial singlet state of spins 1–2 occupies spins 3–4. Then, we induce exchange coupling J between spins 1 and 2 for a variable amount of time. The measured singlet-return probability of spins 1 and 2 will contain an oscillatory component of the form

We also allow spins 3 and 4 to evolve for a variable length of time in the presence of a hyperfine gradient while separated. In this case, the measured singlet-return probability of spins 3 and 4 will contain an oscillatory component of the form

The results of these experiments are shown in the insets of Fig. 3c, d. The presence of large-amplitude oscillations on both sides with the expected phases provides further evidence of successful transfer of both spin-up and spin-down eigenstates from spin 3 to 1 and a singlet state from spins 1–2 to 2–3 during the AQT process. Note that the exchange oscillations of spins 1–2 have different phases for f = ±1, as expected.

Our data provide strong evidence that both single-spin eigenstates and two-spin singlet states, which are also eigenstates of the exchange operator, are correctly transferred by the AQT process. Figure 3c, d provide evidence that spin eigenstates can be transferred from dot 3 to dot 1. The transfer of the singlet state can be viewed as the corresponding process that transfers the state of dots 1–2 to 2–3. The coherent evolution of the singlet state after the AQT process provides evidence of its successful transfer. In the future, as discussed further below, complete state and process tomography will be required to assess the performance of AQT for arbitrary quantum states.

Relationship to counterintuitive adiabatic transfer

The AQT sequence described above, which transfers the state of dot 3 to dot 1, partially resembles the “counterintuitive” adiabatic transfer sequence used in optical systems24,30. The sequence of Fig. 3a transfers a spin state from dot 3 to dot 1, yet the sequence begins with a strong exchange coupling between dots 1 and 2, neither of which contains the state to be transferred.

However, a true counterintuitive adiabatic process relies on the existence of a “dark state,” which contains no excitation of the intermediate state. In the present case, the desired dark state would feature no evolution of the second spin in a three-spin chain. Although it is possible to create a dark state in a spin chain with an XX (Ising) coupling24, the dark state does not occur for the general case of an exchange-coupled (Heisenberg) spin chain24. However, specific combinations of the exchange couplings and magnetic-field differences between dots can yield a true counterintuitive adiabatic sequence24,36.

In general, it is possible to implement the AQT process described above with spins 1 and 2 configured as any eigenstate of the exchange operator, including either of the polarized triplet states, which do not evolve under exchange coupling. However, as Fig. 2 shows, many of the configurations involving other eigenstates of exchange pass through degeneracies at the beginning and the end of the time evolution, complicating the transfer process. We return to this point below when we estimate the fidelity of the AQT process.

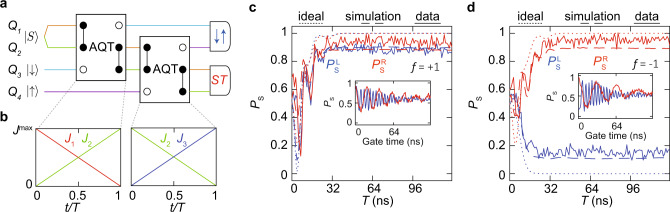

AQT cascade

The AQT process described above transfers spin states among three electrons. We now show that AQT processes can be cascaded to enable long-distance state transfer. We use two AQT steps in a chain of four spins [Fig. 4a]. We initialize the spin chain in the state

AQT Cascade.

a Quantum circuit diagram for the experiment. We initialize the spins as

Figure 4c, d show the cases for f = +1 and −1, respectively. Even though the data of Fig. 4c, d involve two AQT steps, the maximum transfer probability appears higher than the data of Fig. 3c, d, which involve one AQT step and two SWAP gates. We attribute this difference to the relative insensitivity of the AQT process to noise and pulse errors, as compared to the SWAP gates. This difference highlights the robustness and potential usefulness of AQT in quantum-dot spin chains. Our simulations agree with our measurements.

As before, we induce exchange between spins 1–2 and singlet-triplet evolution between spins 3–4 following the state transfer. The data from these measurements are shown in the insets of Fig. 4c, d. The presence of prominent oscillations with the expected phases in both cases provides further evidence of successful transfer of single-spin eigenstates and two-spin singlet states.

As in Fig. 3c, d, the data of Fig. 4c, d show oscillatory features at small values of T, which are related to resonant adiabatic quantum-state transfer24. These resonances in the non-adiabatic limit provide a shortcut to adiabatic quantum-state transfer. In the present experiment, effects associated with the hyperfine gradient broaden and reduce the overall height of the resonant peaks. We expect that resonant adiabatic transfer should work better in Si spin qubits, where nuclear spin effects are suppressed.

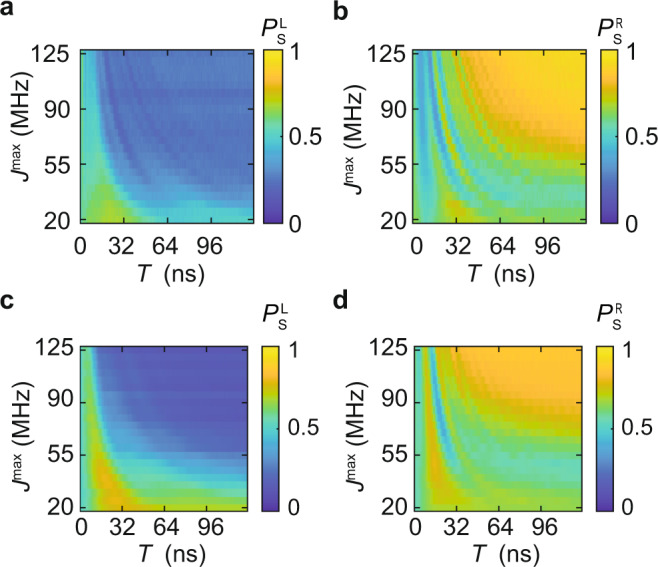

To further explore effects associated with the speed of the state transfer, we plot measurements of the cascaded AQT probability as we vary T and Jmax (Fig. 5). We find that increasing Jmax or T both correlate with higher transfer probability. This is expected, because the condition for adiabatic transfer is JmaxT/ℏ ≫ 124. We also observe prominent features associated with resonant adiabatic transfer, especially at low values of T. Although harnessing resonant adiabatic transfer requires more precise control pulses than adiabatic transfer, it provides a route to distant state transfer in shorter times than adiabatic transfer.

Effects of maximum coupling strength Jmax and interpolation time T.

a Singlet-return probability of the left pair, and b the right pair as a function of Jmax and T. c, d Simulations corresponding to (a) and (b), respectively. During this experiment, we observed that in most cases f = −1. Data presented in the first row are post-selected for f = −1 (see “Methods” and Supplementary Information).

Fidelity estimate

Although we have not performed state tomography to definitively assess the AQT performance, we may estimate its fidelity as follows. The simulations presented in Figs. 3, 4, and 5 take into account state preparation and measurement (SPAM) errors, as well as hyperfine noise, low-frequency charge noise, high-frequency charge noise, and pulse imperfections. The levels of average hyperfine fields and their fluctuations are chosen to replicate the observed coherence of singlet-triplet oscillations in our device. The magnitude of the low-frequency exchange-coupling noise is chosen to replicate the observed exchange-oscillation quality factors in our device. We have also included white high-frequency charge noise (see “Methods”). The simulations show good quantitative agreement with our data.

To estimate the probability of correctly transferring a single-spin eigenstate via a single AQT process, we simulate a three-spin system in the initial state

Table 1 lists some of the results of these calculations. We find that both simulated probabilities exceed 0.95 for the experimental parameters studied here (single-spin

| 1 − f1 | 1 − f23 | 1 − f1 | 1 − f23 | 1 − f1 | 1 − f23 | |

| AQT | 1 × 10−2 | 3 × 10−2 | 1 × 10−3 | 2 × 10−3 | 6 × 10−5 | 1 × 10−4 |

| S12S23 | 3 × 10−2 | 1 × 10−1 | 7 × 10−3 | 1 × 10−2 | 5 × 10−3 | 7 × 10−3 |

We may extend this calculation to compute the expected transfer probability for single-qubit superposition states. We compute the transfer probability for

| 1 − f1 | 1 − f23 | 1 − f1 | 1 − f23 | 1 − f1 | 1 − f23 | |

| AQT | 2 × 10−1 | 3 × 10−2 | 2 × 10−3 | 2 × 10−3 | 8 × 10−4 | 1 × 10−4 |

| S12S23 | 5 × 10−2 | 1 × 10−1 | 7 × 10−3 | 1 × 10−2 | 5 × 10−3 | 7 × 10−3 |

We can also assess the expected transfer probability for the different states of spins 1 and 2, including the eigenstates of the exchange operator. In this case, we define an initial state of the three-electron system as

Finally, we may also simulate the process fidelity for transferring single-spin states via AQT. For electron spins in GaAs, the maximum simulated process fidelity to correctly transfer a single-spin state from dot 3 to dot 1 is about 0.7 at a total time of about 15 ns. This simulation agrees with the transfer probabilities listed above. It is not meaningful to ascribe a process fidelity for the transfer of the two-spin state, because AQT requires that the remaining two spins are in an eigenstate of exchange coupling at the beginning and end of the AQT. Spins 1 and 2 in the experiment of Fig. 3a cannot, for example, have an arbitrary two-qubit state, similar to the requirement for an entangled state in conventional teleportation.

The primary limiting factor in these probabilities for GaAs quantum dots is the nuclear hyperfine gradient. First, the magnetic gradient limits the fidelity of the singlet state preparation. Second, a static magnetic gradient will tend to decrease the energy gaps in the system, requiring a slower pulse, or lowering the overall transfer fidelity for a pulse of the same speed (see Supplementary Information). Third, hyperfine fluctuations that quasistatically increase the magnetic gradients will also tend to decrease the adiabaticity during the pulse and lower the fidelity.

In Si spin qubits, where nuclear hyperfine fields are suppressed, we expect that AQT can enable high-fidelity transfer of arbitrary states (see Supplemental Material for further information on experimental procedures, calculations, and simulations)24,36. For example, when

The AQT fidelity in our experiment is also affected by exchange-coupling calibration errors and charge noise, and this limitation will become more important in Si quantum dots. Our current method of exchange-coupling control lets us set the couplings with an accuracy of about 10 MHz10. Although we intend to ramp the exchange couplings linearly, errors in our exchange-coupling calibration can cause slight deviations from a linear ramp. In the future, more accurate modeling and control of exchange couplings should enable higher-fidelity state transfer. High-frequency charge noise can also have a similar effect. These deviations can reduce the overall fidelity, especially if the couplings are ramped more quickly than intended. We predict that high-frequency charge noise will be the limiting factor for AQT fidelities in Si quantum dots. The levels of quasi-static low-frequency charge noise in quantum dots have minimal effect on AQT, which is robust against small changes to the beginning and ending exchange-coupling values.

Discussion

Our experiments show that AQT is a promising tool for quantum-state transfer in semiconductor quantum-dot spin chains. Unlike methods for state transfer based on shuttling, AQT involves transferring quantum states without moving the qubits themselves, simplifying the process.

Exchange-based SWAP gates can also transfer spin states without moving electrons11,17. The simulation results shown in Table 1 indicate that AQT is more effective than a sequence of SWAP gates at transferring both eigenstates and spin singlets for the range of experimental parameters studied here. In particular, the SWAP sequence is vulnerable to errors associated with evolution of the singlet state in a magnetic gradient, although this evolution can in principle be corrected for via additional gates11. Table 1 also suggests that the fluctuating hyperfine field is the dominant source of error, for both AQT and SWAP sequences, compared with exchange-coupling noise resulting from charge noise.

In the case of superposition states, both AQT and the SWAP sequence are not very effective when

In the future, state and process tomography, both requiring single-spin control and readout, will be required to definitively assess the performance of AQT for arbitrary qubit states. In particular, demonstrating an average single-qubit state transfer probability above the classical bound of 2/349, or a process fidelity above 1/250, would verify the quantum-mechanical nature of this process. Measurements in addition to those presented here, which involve single-spin eigenstates, are needed to verify the quantum nature of the AQT process.

The AQT method implemented here is a highly robust method for the transfer of spin eigenstates and singlets in GaAs semiconductor quantum-dot arrays. The transfer of spin eigenstates is essential for readout in spin chains, and given the critical importance of spin singlets for various quantum information processing tasks, such as teleportation12 and superexchange51,52, it is likely that state transfer via both AQT and SWAP gates will find use in spin-based quantum computing algorithms. We also expect that AQT will enable the high-fidelity transfer of arbitrary single-qubit states in Si spin qubits. However, the AQT process takes about ten times longer than a sequence of SWAP gates. Furthermore, while AQT transfers single-spin states between next-nearest-neighbor dots, SWAP gates transfer spin states between nearest-neighbor dots. From this point of view, the strengths of AQT complement the strengths of state transfer via SWAP gates.

To conclude, our measurements provide evidence for adiabatic quantum-state transfer of both single-spin eigenstates and two-spin singlet states. We have also shown that the AQT protocol can be cascaded for efficient and robust quantum information transfer in a chain of semiconductor quantum-dot spin qubits. We believe that AQT will enable quantum-state transfer in long chains of spin qubits for initialization, operation, and measurement in gate-based quantum computing architectures. An exciting prospect for future work is to harness many-body quantum states for direct, long-distance AQT28,29. This work also opens up the possibility of adiabatic single-qubit state- and gate-teleportation, as well as universal adiabatic quantum computing, in semiconductor quantum-dot spin qubits.

Methods

Device

Our quadruple quantum-dot device is fabricated on a GaAs/AlGaAs semiconductor heterostructure. The two-dimensional electron gas (2DEG) resides at the interface between the GaAs and AlGaAs layers, 91 nm below the surface of the wafer. The density and mobility of carriers in the 2DEG at a temperature of 4 K are 1.5 × 1011 cm−2 and 2.5 × 106 cm2/Vs, respectively. Aluminum gates are arranged in a three-layer overlapping gate architecture and are fabricated using electron-beam lithography. An additional top gate, not shown in Fig. 1a in the main text, covers all of the gates and the space around the center of device. Each of these metal gates is separated by a thin layer of native oxide formed on the gate surface. Voltages applied to the gates confine the electrons in the 2DEG. Each dot contains only one electron, and their chemical potentials are roughly the same, which we refer to as the symmetric configuration. The plunger and barrier gates are connected to arbitrary waveform generator channels via homemade bias-tees. This configuration enables fast initialization, manipulation, and readout of the spins. Further details about the device are given in ref. 11.

Orthogonal control of the chemical potentials and exchange couplings

Our device has four plunger gates [p1, p2, p3, p4] for chemical potential control, three barrier gates [b1, b2, b3] for controlling the tunnel coupling between adjacent dots, and leads [L1, L2] for controlling the system-environment interaction. In order to achieve individual control over the chemical potentials and exchange couplings, we define a set of virtual gates

State preparation and readout

For initialization and readout, we configure the quadruple quantum-dot chain into two pairs. Dots 1 and 2 form the “left” pair and dots 3 and 4 form the “right” pair. We initialize the system in the (2, 0, 0, 2) charge state by lowering the chemical potentials of dots 1 and 4 below the Fermi level of the corresponding reservoir, while holding the chemical potentials of dots 2 and 3 above the Fermi level of that reservoir. The ground state of a pair of electrons in a single dot is the singlet state. We transfer one electron each from dots 1 and 4 into dots 2 and 3, respectively. Diabatic charge transfer maintains the joint spin states of the electrons, while adiabatic charge transfer prepares the electrons in spin eigenstates. We can also initialize either pair in the

The state preparation estimates in the main text were obtained by initializing the dots in a particular state and measuring it. To estimate the singlet-state preparation fidelity on the left side, we load two electrons in dot 1 in the singlet state, transfer one of the electrons diabatically to dot 2, and project the spin-state of the electrons in dots 1 and 2 by diabatic transfer of the electron from dot 2 back to dot 1. Similarly, to estimate the fidelity of initializing the right pair in the ground state of the hyperfine field gradient, we load two electrons into dot 4 in the singlet state, transfer one of them adiabatically to dot 3, and then project the spin state of the electrons by adiabatic charge transfer of electron from dot 3 back to dot 4.

The experimental data of Figs. 3 and 4 in the main text involve measuring a singlet in the right pair. Generally, diabatic charge transfer together with a Pauli spin-blockade measurement suffices to measure a pair of electrons in the singlet-triplet basis42,43. However, the small inter-dot tunnel coupling limits the fidelity of diabatic projection in our device. To measure a pair of electrons in the singlet-triplet basis in our device, we implemented a modified pulse sequence in which the electron pair is first evolved under the two-electron Hamiltonian

Ground state of the magnetic-field gradient

To prepare the spin chain in a product state with Sz = 0, we load two electrons in dots 1 and 4 each and transfer one electron from each of them to dots 2 and 3 adiabatically. The particular orientation of the spins in the chain after this step depends on the ground state of the hyperfine field gradient on both sides42,43. Since the hyperfine field fluctuates in time, the gradient also changes, and so does the ground-state spin configuration. Because our experiments involve preparing spin states on one side of the array and transferring them to the other side before the measurement, knowledge of the hyperfine configuration is critical. As we now discuss, we can monitor not only the sign of the gradients but also the ground-state spin configurations of the left and right sides in real time by measuring the evolution of the spin states in dots 2–3 under exchange coupling.

We define

To determine the ground-state spin orientation, we load the left side in the

Post-selection of data

The ground-state spin orientation of the spin chain was monitored during experiments by interleaving the pulses discussed above. Specifically, we interleaved measurements of exchange between spins 2 and 3 with the GG and T+G configurations (Supplementary Fig. 2). Here, G denotes the two-spin ground state of the hyperfine field gradient in the Sz = 0 subspace, and T+ denotes spin pairs in the

The data associated with Figs. 3 and 4 in the main text consist of many repetitions. Each repetition, which consists of 512 or 256 single-shot measurements for Figs. 3 and 4, respectively, corresponding to each value of T, was assigned a value of f based on the interleaved measurement discussed above. Individual repetitions with different values of f are displayed in the main text. The data from all repetitions of the AQT experiments, as well as the average of the f = ±1 cases corresponding to Figs. 3, 4, and 5 of the main text are shown in Supplementary Figs. 3, 4, and 5, respectively. The averages across all f = ±1 cases do not differ substantially from the individual repetitions displayed in the main text.

Indirect AQT transfer probability assessment

As an indirect qualitative indicator of the AQT transfer probability, we transferred states of the spin chain initialized in the state

Simulation

We accounted for known sources of errors and noise to reproduce experimental observations in the simulations. Load errors associated with the singlet, and the hyperfine ground state with Sz = 0 were approximated by

We define time-dependent Hamiltonians acting on the spin chain

To simulate the AQT and SWAP experiment described in Fig. 3 in the main text, the spin chain was initialized in the state

The final state of the spin chain after the AQT and SWAP operations U34 and U23 is

Similarly, for the simulation of the cascaded AQT experiment described in Fig. 4 of the main text, the initial state was set as

Finally, the singlet-return probabilities were calculated as

The magnetic field in all simulations incorporates both the externally applied magnetic field of 0.5 Tesla and the local hyperfine field. The values of the hyperfine field and its fluctuations were adjusted for better agreement between the simulation and the experimental data, and the specific values are presented in Supplementary Table 1.

Charge noise directly affects the strength of exchange couplings. Low-frequency noise in the exchange couplings for each realization of the simulation was incorporated by sampling the exchange couplings from a Gaussian distribution with a target mean value (J0) and standard deviation equal to

To include errors due to relaxation during the measurement, we define

Specific values of tm, T1, and fr used in the simulations are 4 μs, 60 μs, and 0.99 for the left side, and 6 μs, 50 μs, and 0.95 for the right side, respectively. These values were obtained from the experiment.

State-transfer fidelity estimation

To estimate the probability of correctly transferring single-spin and two-spin states via a single AQT process, we simulate a three-spin system in the initial state

Supplementary Figs. 7, 8, and 9 show the simulated transfer probability for different initial states of spins 1–2 and spin 3 vs. single-spin

Process fidelity simulation

To estimate the process fidelity associated with transferring single-spin states via a single AQT process, we simulate a three-spin system in the initial state

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41467-021-22416-5.

Acknowledgements

This work was sponsored by the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency under Grant No. D18AC00025, the Army Research Office under Grant Nos. W911NF-16-1-0260 and W911NF-19-1-0167, and the National Science Foundation under Grant Nos. DMR-1941673 and DMR-2003287. The views and conclusions contained in this document are those of the authors and should not be interpreted as representing the official policies, either expressed or implied, of the Army Research Office or the U.S. Government. The U.S. Government is authorized to reproduce and distribute reprints for Government purposes notwithstanding any copyright notation herein.

Author contributions

Y.P.K., H.Q., and J.M.N. conceptualized the experiment and analyzed the data. Y.P.K. and H.Q. conducted the investigation. S.F., G.C.G., and M.J.M. provided resources. All authors participated in writing. J.M.N. supervised the effort.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

References

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

6.

7.

8.

9.

10.

11.

13.

14.

15.

16.

17.

18.

19.

20.

21.

22.

23.

24.

25.

26.

27.

28.

29.

30.

31.

32.

33.

34.

35.

36.

37.

38.

39.

40.

41.

42.

43.

44.

45.

46.

47.

48.

49.

50.

51.

52.

53.

54.

55.

56.

57.

Adiabatic quantum state transfer in a semiconductor quantum-dot spin chain

Adiabatic quantum state transfer in a semiconductor quantum-dot spin chain