- Altmetric

The transfer of information between quantum systems is essential for quantum communication and computation. In quantum computers, high connectivity between qubits can improve the efficiency of algorithms, assist in error correction, and enable high-fidelity readout. However, as with all quantum gates, operations to transfer information between qubits can suffer from errors associated with spurious interactions and disorder between qubits, among other things. Here, we harness interactions and disorder between qubits to improve a swap operation for spin eigenstates in semiconductor gate-defined quantum-dot spins. We use a system of four electron spins, which we configure as two exchange-coupled singlet–triplet qubits. Our approach, which relies on the physics underlying discrete time crystals, enhances the quality factor of spin-eigenstate swaps by up to an order of magnitude. Our results show how interactions and disorder in multi-qubit systems can stabilize non-trivial quantum operations and suggest potential uses for non-equilibrium quantum phenomena, like time crystals, in quantum information processing applications. Our results also confirm the long-predicted emergence of effective Ising interactions between exchange-coupled singlet–triplet qubits.

Information transfer between distant qubits suffers from spurious interactions and disorder. Here, the authors report up to an order of magnitude enhancement in the quality factor of a swap operation of eigenstates in a quantum dot chain, by using a periodic driving protocol inspired by discrete time crystals.

Introduction

Over the past decades, quantum information processors have undergone remarkable progress, culminating in recent demonstrations of their astonishing power1. As quantum information processors continue to scale-up in size and complexity, new challenges come to light. In particular, maintaining the performance of individual qubits and high connectivity are both essential for continued improvement in large systems2.

At the same time, developments in nonequilibrium many-body physics have yielded insights into many-qubit phenomena, which feature, in some sense, improved performance of many-body quantum systems when disorder and interactions are included. Chief among these phenomena are many-body localization3 and time crystals4–8. Although these phenomena are interesting in their own right, applications of these concepts are only beginning to emerge.

In this work, we exploit discrete-time-crystal (DTC) physics to demonstrate Floquet-enhanced spin-eigenstate swaps in a system of four quantum dot electron spins. When we harness interactions and disorder in our system, the quality factor of spin-eigenstate swaps improves by nearly an order of magnitude. As we discuss in detail further below, this system of four exchange-coupled single spins undergoing repeated SWAP pulses maps onto a system of two Ising-coupled singlet–triplet (ST) qubits undergoing repeated π pulses. Periodically driven Ising-coupled spin chains are the prototypical example of a system predicted to exhibit DTC behavior4. Experimental signatures of DTC behavior have been observed in many systems9–12, but nearest-neighbor Ising-coupled spin chains have yet to be experimentally investigated in this regard.

Our system of two ST qubits is clearly not a DTC in the strict sense, because it is not a many-body system13. However, this system does exhibit some of the key characteristics of DTC behavior, including robustness against interactions, noise, and pulse imperfections13,14. We also find that the required experimental conditions for observing the quality-factor enhancement are identical to some of the theoretical conditions for the DTC phase in infinite spin chains. In total, these observations suggest the Floquet-enhanced spin-eigenstate swaps in our device are closely related to discrete time-translation symmetry breaking.

Our results also illustrate how nonequilibrium many-body phenomena could potentially be used for quantum information processing. On the one hand, we observe Floquet-enhanced π rotations in two ST qubits. But on the other hand, these ST π rotations correspond to spin-eigenstate swaps, when we view the system as four single spins. The enhanced spin-eigenstate swaps are not coherent SWAP gates, but instead are “projection-SWAP” gates15. Because of the critical importance of such operations for reading out linear qubit arrays, these results may point the way toward the use of nonequilibrium quantum phenomena in quantum information processing applications, especially for initialization, readout, and information transfer. Moreover, recent theoretical work shows how entangled states can be preserved, and robust single-, and two-qubit gates can be implemented, within this framework16. Our results are also significant because they provide experimental evidence of the predicted Ising coupling that emerges between exchange-coupled ST qubits17.

Results

Device and Hamiltonian

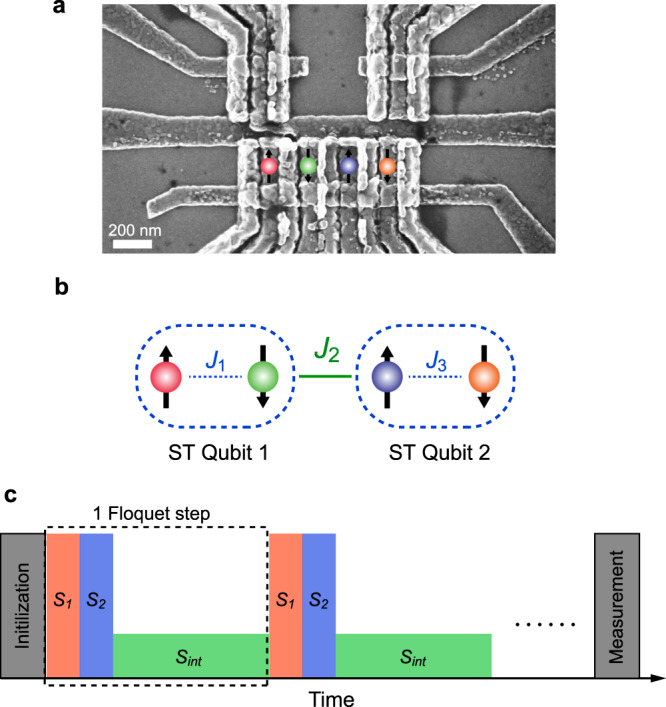

We fabricate a quadruple quantum dot array in a GaAs/AlGaAs heterostructure with overlapping gates (Fig. 1a)18–20. The confinement potentials of the dots are controlled through “virtual gates”21–24. Two extra quantum dots are placed nearby and serve as fast charge sensors25,26. We configure the four-spin array into two pairs (“left” and “right”) for initialization and readout. Each pair of spins can be prepared in a product state ( or

Experimental setup.

a Scanning electron micrograph of the quadruple quantum dot device. The locations of the electron spins are overlaid. b Schematic showing the two-qubit Ising system in a four-spin Heisenberg chain. c The pulse sequence used in the experiments.

The four-spin array is governed by the following Hamiltonian:

Heisenberg exchange coupling does not naturally enable the creation of a DTC phase8. Additional control pulses can convert the Heisenberg interaction into an Ising interaction8, which permits the emergence of a DTC phase. A DTC can also be created using a sufficiently strong magnetic field gradient instead of applying extra pulses34. Here, we introduce a new method for generating DTC behavior that does not require complicated pulse sequences or large field gradients, but instead relies only on periodic exchange pulses.

To see how we can still obtain an effective Ising interaction in this case, it helps to view each pair of spins as an individual ST qubit (Fig. 1b)27. Specifically, consider the scenario where the joint spin state of each pair is confined to the subspace spanned by

In the case when J2 = 0, but when J1, J3 > 0, the overall Hamiltonian describes two uncoupled ST qubits. Thus, let us define

In the

Floquet-enhanced spin swaps

We define a Floquet operator U = Sint ⋅ S2 ⋅ S1 (Fig. 1c), and we repeatedly apply this operator to our system of four spins. As discussed above, U implements spin SWAP gates between spins 1–2 and 3–4 followed by a period of exchange interaction between spins 2 and 3. Equivalently, U implements π pulses on both ST qubits and then a period of Ising coupling between them. One might naively imagine that the highest fidelity SWAP operations between spins should occur when J2 = 0 and τ = 0, given the presence of intraqubit hyperfine gradients. In this case, as we have discussed in ref. 29, repeated SWAP operations are especially susceptible to errors from the hyperfine gradients Δij.

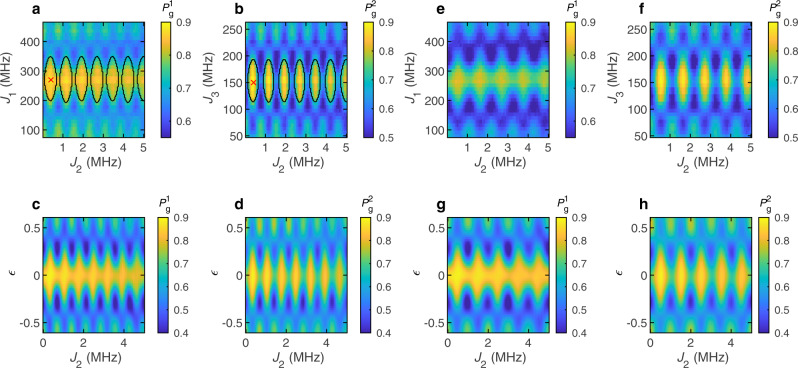

However, by allowing J2 > 0 and τ > 0, we find specific conditions in which we observe a significant enhancement of the spin-eigenstate-swap quality factor (Fig. 2). To explore this phenomenon, we prepare each ST qubit in

Floquet-enhanced π rotations.

a, b Measured ground-state return probabilities of (a) ST qubit 1 and (b) ST qubit 2, after four Floquet steps, with interaction time τ = 1.4 μs. The ranges of J1 and J3 center around

First, we set the interaction time τ = 1.4 μs and SWAP pulse times t1 = t2 = 5 ns, and apply four Floquet steps. We sweep J2 linearly from 0.05 to 5 MHz (Fig. 2a, b). (Setting J2 < 0.05 MHz would require large negative voltage pulses applied to the barrier gate due to the residual exchange, which could disrupt the tuning of the device.) We also sweep J1 from 80 to 460 MHz, and J3 from 50 to 260 MHz. The ranges of J1 and J3 roughly center around

Clear, bright diamond patterns are visible in the data (Fig. 2a, b). These bright regions correspond to improved spin-eigenstate-swap quality factors. Note that the brightest regions correspond to configurations when J2 > 0. Note also that the diamonds are approximately periodic in J2τ, as expected for a Floquet operator. We repeat the same experiments with τ = 1μs, and we observe similar diamond patterns, although they have an increased period in J2 (Fig. 2e, f). The diamond patterns of ST qubit 2 appear narrower due to the large hyperfine gradient Δ34, which causes larger pulse errors and reduces the size of the quality-factor-enhancement region. These data from an effective two-qubit system resemble predicted DTC phase diagrams of a true nearest-neighbor many-body system (see “Methods” and Supplementary Figs. 2 and 3)7,8.

Our simulations agree well with the data (Fig. 2c, d, g, h; see “Methods”). In the simulations, the diamond pattern is periodic in J2τ with the periodicity of exactly 1, and the strongest quality-factor enhancement occurs at J2τ = 0.5. In the experimental data, however, the periodicity is slightly larger than 1, and the strongest quality-factor enhancement occurs at J2τ > 0.5. This is due to the imperfect calibration of the exchange coupling J2 (ref. 32). In particular, the presence of the hyperfine field gradient makes it difficult to measure and control the exchange couplings with sub-MHz resolution. If our modeling of the exchange coupling were more precise, then we would expect the periodicity of the diamond patterns to be closer to 1 and the quality-factor enhancement to occur closer to J2τ = 0.5 in the experimental data.

We can interpret our data using a semiclassical model inspired by Choi et al. in ref. 10 to explain DTC behavior (see “Methods”). In brief, an initial state of ST qubit 1,

Next, we also sweep J3 from 220 to 430 MHz. In this case, the range of J3 roughly centers around

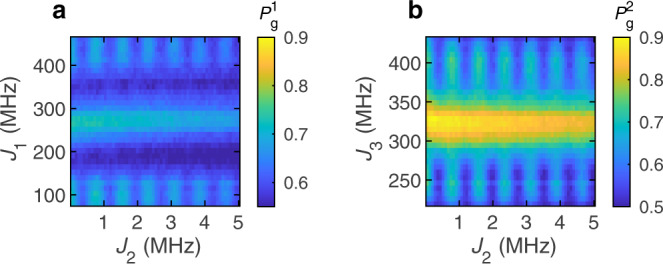

Absence of Floquet enhancement due to the omission of a π pulse.

a, b Measured ground-state return probabilities of (a) ST qubit 1 and (b) ST qubit 2, after four Floquet steps, with interaction time τ = 1.4 μs. The ranges of J1 and J3 center around

On the one hand, this effect is striking, when one considers the individual spins themselves. Recall that the ST-qubit splittings Δ12 and Δ34 are generated by the hyperfine interaction between the Ga and As nuclei in the semiconductor heterostructure and the electron spins in the quantum dots. Although Δ12 and Δ34 are quasistatic on millisecond timescales, they each independently fluctuate randomly, and can change sign, over the duration of a typical data-taking run, which is ~1 h. Each of the 8192 different realizations for each pixel in the data of Fig. 2 likely contain instances, where both ST qubits have the same or different ground-state spin orientations. (The ground state of each ST qubit is either

Thus, the data of Fig. 2 likely include realizations with all possible combinations of the orientations of spins 2 and 3 before the interaction period. Despite the random orientations of spins 2 and 3, the Floquet enhancement still appears. It might therefore seem that whether or not spins 1–2 or 3–4 undergo a SWAP before the interaction period should not affect the behavior of the system. However, as shown in Fig. 3, implementing a 2π rotation, as opposed to a π rotation, on one of the ST qubits eliminates the Floquet enhancement.

On the other hand, when one considers the semiclassical picture described above, the absence of a π pulse on one of the ST qubits spoils the semiclassical decoupling evolution discussed above and in ref. 10. In this case, ST-qubit eigenstates are no longer eigenstates of two instances of the Floquet operator, and the enhancement no longer occurs.

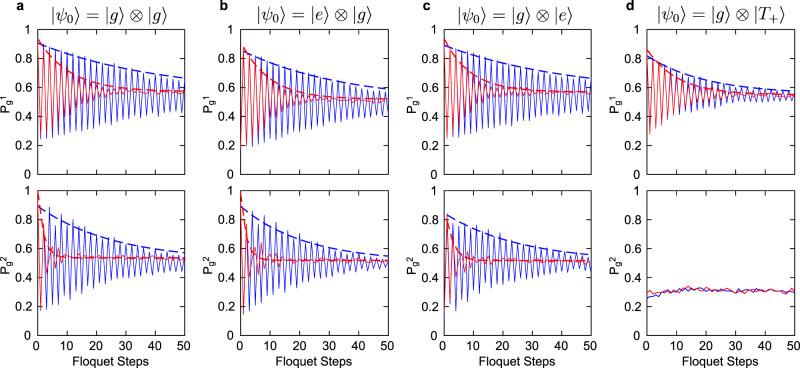

We have now determined the optimal conditions for the Floquet enhancement. For the remainder of the paper, we set J1 = 270 MHz and J3 = 150 MHz with t1 = t2 = 5 ns for the SWAP operators S1 and S2, respectively, and we set τ = 1.4 μs and J2 = 0.41 MHz for the Ising interaction. To quantify the Floquet enhancement, we evolve the system for 50 Floquet steps and measure the ground-state return probabilities for both qubits after each step. The results are shown in Fig. 4a. Note that the system exhibits a clear subharmonic response to the Floquet operator. We extract a swap quality Q by fitting the data with a decaying sinusoidal function

Floquet-enhanced spin swaps.

a–d Quality-factor enhancement of spin-eigenstate swaps for different initial states. In each figure, the top panel shows the measurements of ST qubit 1, and the bottom panel shows the measurements of ST qubit 2. The initial states are shown on the top, where

We find a ~3-fold quality-factor improvement on qubit 1, and ~9-fold improvement on qubit 2. The significant discrepancy between the quality-factor improvements of the two qubits is likely due to the large hyperfine gradient Δ34 in qubit 2, which causes an exceptionally low quality factor for non-enhanced π rotations. The quality-factor enhancement is striking in this case. To extract an estimated uncertainty, we repeat the same experiment 30 times, and calculate the mean and the standard deviation of the quality-factor ratio, as shown in the first row of Table 1.

| Initialization | Quality-factor enhancement | |

|---|---|---|

| Qubit 1 | Qubit 2 | |

| 3.60 ± 0.89 | 8.47 ± 3.29 | |

| 3.24 ± 0.94 | 9.33 ± 2.96 | |

| 3.15 ± 0.79 | 9.10 ± 2.87 | |

| 1.92 ± 0.27 | N/A | |

So far, we have initialized both ST qubits in their ground states. We can also initialize either ST qubit in its excited state by applying an extra π pulse to the qubit immediately before the first Floquet step. We run the same experiment with different initial states and extract the quality factors by fitting the data (Fig. 4b, c). Again, for each initial state, we repeat the experiment 30 times and calculate the mean and the variance of the quality-factor ratio, which are listed in Table 1. The quality-factor improvements of both qubits are consistent across different initial states.

We also initialize the right pair as

Finally, we emphasize that a Floquet drive, i.e., repeated SWAP gates, is required to realize the enhancement shown in Fig. 4. Based on the data of Fig. 4, the first SWAP gate is not substantially enhanced by the protocol. It is only subsequent SWAP gates that are enhanced. This is consistent with the requirement for a periodic drive in a DTC. As we discuss below, this periodic drive is also useful for constructing quantum gates.

Discussion

Strictly speaking, a DTC only occurs in the thermodynamic limit13. Nonetheless, we argue the quality-factor enhancement we observe relies on the essential elements of DTC physics. The disordered Ising-coupled system in our device demonstrates a clear subharmonic response, as well as a robustness against pulse errors, both expected as defining signatures of the DTC. Our experiments also indicate the necessity of two essential ingredients for realizing the Floquet-enhanced π pulses: (1) an effective Ising interaction, and (2) global π pulses. If either of the components is missing, we no longer observe the significant quality-factor enhancement (Figs. 3 and 4d). These two components both ensure that the semiclassical dynamical decoupling can occur. In the thermodynamic limit, these components would ensure that eigenstates of the Floquet operator are long-range correlated, which is required for discrete time-translation symmetry breaking5. We have also shown that the quality-factor enhancement does not depend on the eigenstate into which either ST qubit is initialized (provided that the effective Ising coupling is maintained), which is another key feature of the DTC13. In the future, implementing these experiments in larger spin chains could lead to a verification that these effects in fact originate from the DTC phase.

We emphasize that we have observed Floquet enhancement associated with ST-qubit eigenstates undergoing π pulses. In the language of single spins, we observed Floquet enhancement associated with swaps between spin eigenstates, when the total z component of angular momentum for both spins vanishes. This observation is qualitatively consistent with expectations for qubits in a true many-body DTC, where the components of the qubits oriented along the direction defined by the Ising coupling are preserved8. While not a coherent SWAP gate, a spin-eigenstate swap (projection-SWAP), has significant potential to aid in readout for large qubit arrays41.

The Floquet enhancement we observe can immediately be leveraged to perform additional quantum information processing tasks of significant importance. For example, recent theoretical work shows that entangled states of single spins (or superposition states of ST qubits) can be preserved, using Floquet operators identical to what we have demonstrated16. The same work also shows that single-qubit gates can be incorporated into this framework, and even two-qubit CZ gates can be implemented16. A significant potential advantage of these operations, compared with conventional single- and two-qubit gates, is that dynamical decoupling is an essential component of these operations, as discussed above.

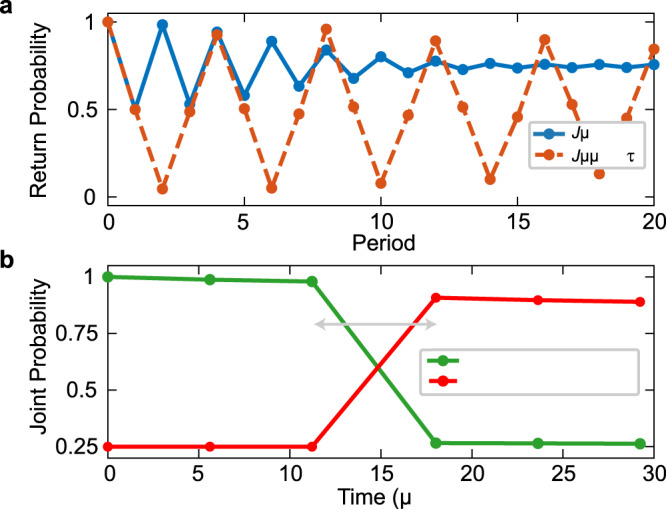

As an illustration of the above capabilities, we perform simulations that show the preservation of the singlet state of an ST qubit by periodic driving under the evolution U = Sint ⋅ S12, where S12 represents the execution of S1 and S2 in parallel. Figure 5a shows the return probability for the singlet state of an ST qubit defined on sites 3 and 4 of an L = 6 site spin chain. The ST qubits defined on the pairs of sites (1,2) and (5,6) are initialized to the product state

Preserving and generating entangled states.

a Return probability for the singlet state of an ST qubit defined on sites 3 and 4 of an L = 6 spin chain. The two remaining ST qubits are initialized in the state

The condition τJ = 0.25 also serves to implement a two-qubit CZ gate, for which simulations are shown in Fig. 5b for the L = 4 chain. Here, the ordinary DTC protocol with τJ = 0.5 is applied for eight periods, followed by two periods with the reduced value τJ = 0.25. Since the effective interaction between ST qubits is of Ising form, this yields a CZ gate up to single-qubit z rotations:

The experimental investigation of all of these ideas remains an important subject of future work. We expect that these phenomena can readily be explored in Si spin qubits. Barrier-controlled exchange coupling between Si spin qubits is now routine43. The operation of Si ST qubits in the regime where magnetic gradients exceed exchange couplings has also been demonstrated15,44.

Note that to observe the Floquet enhancement, or to perform any of the protocols described in ref. 16, multiple Sz = 0 electron pairs undergoing the same Floquet operators are typically required. As we have shown above, one ST qubit alone cannot experience the Floquet enhancement without the other. This notion is consistent with expectations for many-body DTCs, which are true many-body phenomena. One can view the “extra” qubits undergoing repeated instances of the Floquet operator as the resource required to implement an improved operation on a specific qubit. It is also interesting to note that DTC-like behavior can emerge in systems with as few as two qubits in this nearest-neighbor-coupled system, as we have shown. Thus, only a relatively small number of qubits is required in order to realize the benefits of Floquet enhancement, highlighting its potential for further use in quantum information processing applications.

In summary, we have demonstrated Floquet-enhanced spin-eigenstate swaps in a four-spin two-qubit Ising chain in a quadruple quantum dot array. The system shows a subharmonic response to the driving frequency, and it also shows an improvement in swap quality factor even in the presence of pulse imperfections. We have also shown that the necessary conditions for this quality-factor enhancement are identical to some key components for realizing discrete time crystals. Our results also confirm the prediction of an effective Ising coupling that emerges between two exchange-coupled singlet–triplet qubits. This work indicates the possibility of realizing discrete time crystals using extended Heisenberg spin chains in semiconductor quantum dots, and suggests potential uses for discrete time crystals in quantum information processing applications.

Methods

Device

The quadruple quantum dot device is fabricated on a GaAs/AlGaAs heterostructure substrate with three layers of overlapping Al confinement gates and a final Al top gate. The Al gates are patterned and deposited using E-beam lithography and thermal evaporation, and each layer is isolated from the other layers by a few nanometers of native oxide. The top gate covers the main device area and is grounded during the experiments. It likely smooths anomalies in the quantum dot potentials. The two-dimensional electron gas resides at the GaAs and AlGaAs interface, 91 nm below the semiconductor surface. The device is cooled in a dilution refrigerator with base temperature of ~10 mK. A 0.5-T external magnetic field is applied parallel to the device surface and perpendicular to the axis connecting the quantum dots.

Pulse rise times

The experimental values of

Simulation

We simulate the Floquet-enhanced phenomena by evolving a four-spin array according to the Floquet operator U = Sint ⋅ S2 ⋅ S1, as defined in the main text. We set t1 = t2 = 2 ns, and

For better comparison with the experimental data, the simulations take into account all known error sources, including state preparation, readout, charge noise, and hyperfine field noise. The initial state of each ST qubit is prepared as

We use a Monte-Carlo method to incorporate charge noise and hyperfine field fluctuations. The values of the exchange couplings Ji and the local hyperfine fields

The simulations of Fig. 5 do not include exchange coupling noise or state preparation and measurement errors. We neglected these errors to clearly illustrate the mechanisms underlying the singlet-state preservation and CZ gate. Hyperfine fluctuations with

To confirm that the behavior we report in the two ST qubits corresponds to that of an effective Ising spin chain, we also simulate an Ising spin chain. Define

Supplementary Fig. 3a shows the results of an N = 8 Ising spin chain after four Floquet steps, with

Semiclassical phase diagram calculation

In ref. 10, Choi et al., explain the DTC-like behavior of their system with a semiclassical model. Inspired by their work, we present a related semiclassical model for our system. Let us consider an initial state of ST qubit 1:

In order to see a period doubling in the system, even in the presence of errors, we require that

To write down the actual evolution operator for our system, set

In these definitions, we have suppressed the tildes, although the Pauli operators refer to the ST qubits. As before, S1 describes a nominal π pulse about the x-axis, and

We numerically calculate the eigenvectors of U for the different interaction strengths and pulse errors ϵ we discuss in the manuscript. We will say that when the Floquet eigenstate

This construction clearly illustrates that without interactions or global π-pulses, the robust period doubling will not be observed, as discussed in ref. 10. In this case, the eigenstates of U are the same as the eigenstates of a single Floquet step, and there is no symmetry breaking. Without a global π-pulse, initial states with θ0 ≈ 0 can only be approximately preserved after two Floquet steps (they are not exactly preserved), unlike the case with interactions, where these states are exactly preserved.

This semiclassical calculation is also valid for an end-spin of a longer spin chain, because we are considering a nearest-neighbor Ising chain. The argument we have provided applies to the first spin in the chain, and the interaction part depends on the state of the second spin. In our model, spin 2 is assumed to undergo perfect π pulses. In a long spin chain, this assumption becomes more accurate, because one can view the effect of the third and first spins in the chain as stabilizing the π-rotations on spin 2, and so on.

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41467-021-22415-6.

Acknowledgements

This research was sponsored by the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency under Grant No. D18AC00025, the Army Research Office under Grant Nos. W911NF16-1-0260 and W911NF-19-1-0167, and the National Science Foundation under Grant Nos. DMR-1941673 and DMR-2003287. The views and conclusions contained in this document are those of the authors and should not be interpreted as representing the official policies, either expressed or implied, of the Army Research Office or the U.S. Government. The U.S. Government is authorized to reproduce and distribute reprints for Government purposes notwithstanding any copyright notation herein.

Author contributions

J.VD., E.B., and J.M.N conceptualized the experiment. H.Q., Y.P.K., and J.VD. conducted the investigation. H.Q., Y.P.K., J.VD., E.B., and J.M.N. analyzed the data. S.F., G.C.G., and M.J.M. provided resources. All authors participated in writing. J.M.N. supervised the effort.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

References

1.

2.

3.

4.

6.

7.

8.

10.

11.

12.

13.

14.

15.

16.

17.

18.

19.

20.

22.

23.

24.

25.

26.

27.

28.

30.

31.

32.

33.

34.

35.

36.

37.

38.

39.

40.

41.

42.

43.

Floquet-enhanced spin swaps

Floquet-enhanced spin swaps