- Altmetric

In 1976, Meyer predicted that bend distortions of the nematic director field are complemented by deformations of either twist or splay, yielding twist-bend and splay-bend nematic phases, respectively. Four decades later, the existence of the splay-bend nematic phase remains dubious, and the origin of these spontaneous distortions uncertain. Here, we conjecture that bend deformations of the nematic director can be complemented by simultaneous distortions of both twist and splay, yielding a twist-splay-bend nematic phase. Using theory and simulations, we show that the coupling between polar order and bend deformations drives the formation of modulated phases in systems of curved rods. We find that twist-bend phases transition to splay-bend phases via intermediate twist-splay-bend phases, and that splay distortions are always accompanied by periodic density modulations due to the coupling of the particle curvature with the non-uniform curvature of the splayed director field, implying that the twist-splay-bend and splay-bend phases of banana-shaped particles are actually smectic phases.

The so-called twist-bend and splay-bend nematic liquid crystal phases are important concepts for studying bent-core mesogens. Chiappini et al. use a theory/simulation approach to suggest that the transition proceed via a twist-splay-bend phase which may be obscured by density modulations.

Introduction

The simplest and most common liquid crystal phase is the nematic phase, which is also the most relevant one for optoelectronic applications. The uniaxial nematic (N) phase consists of anisotropic particles that lack positional order but display orientational order as the particles are preferentially aligned along a so-called nematic director . More exotic states of matter can be conjectured if the nematic director is allowed to vary in space, i.e. the average orientation of a particle at position r is defined by a nematic director field

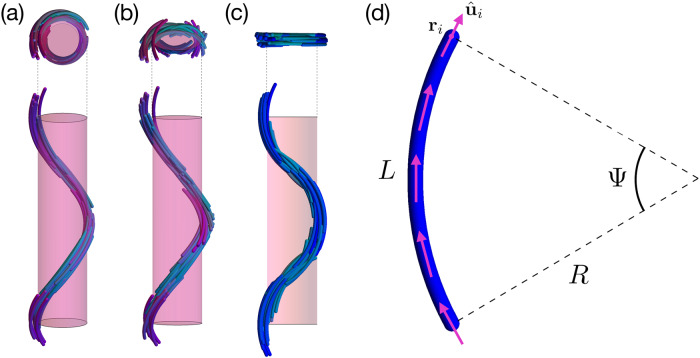

An even more fascinating example is the twist-bend nematic (NTB) phase, recently discovered in experiments on bent-core mesogens1–12. The NTB phase was already predicted by Meyer in 197613 and by Dozov in 200114 for banana-shaped particles that favor spontaneous bend deformations in the nematic director field. As a pure bend deformation cannot uniformly fill the three-dimensional space, local bend deformations have to be accompanied by either a spontaneous twist, yielding an NTB phase, or by splay distortions, resulting into an oscillating splay-bend nematic (NSB) phase, see Fig. 1a, c. The NTB phase is characterised by a nematic director field that precesses around a right circular cone with a pitch p and a conical angle 0 < θ0 < π/2. Hence, the NTB phase is a chiral phase with local polar order and a uniform bend deformation. Because of the achirality of bent-core mesogens, the precession of the nematic director of the NTB phase can be left- or right-handed. On the other hand, the nematic director field of the NSB phase precesses over a flat isosceles triangle with maximum angle θ0, thereby preserving the achiral symmetry and oscillating between non-uniform bend and splay domains, see Supplementary Note 2.

Schematics of a twist-bend, twist-splay-bend, and splay-bend nematic phase of curved rods.

a–c Side and top views of the spatial modulations of the particle orientations in (a) a chiral twist-bend nematic (NTB) phase, b a chiral twist-splay-bend nematic (NTSB) phase and (c) an achiral splay-bend nematic (NSB) phase. d A hard curved spherocylinder consisting of a cylinder of length L and diameter D capped at both ends with a hemisphere of diameter D and bent with a radius of curvature R corresponding to an opening angle Ψ = L/R. In our generalized Maier–Saupe theory, this particle is modelled as a rigid chain of M segments with center-of-mass positions ri and orientations

Many fundamental questions regarding the NTB phase are still open despite numerous theoretical and experimental investigations. Even the most basic question regarding the origin of bend deformations and the appearance of chiral symmetry in systems of achiral bent-shaped particles is still unresolved. While Meyer invoked that bend deformations originate from the spontaneous polar ordering of the particles due to either the molecular shape or the electrostatic polarization13,15, Dozov ignored the possibility of spontaneous polar order and explained the bend distortions by a negative bend elastic constant14. In addition, the relationship between the structure of the NTB phase and the details of the constituent molecules is still not well understood. It is found experimentally that the observation of the NTB phase depends sensitively on the molecular details.

Flexible bent-core molecules linked with an odd number of hydrocarbon atoms display NTB phases but not the ones with an even-numbered linkage16. On the other hand, computer simulations demonstrate the existence of NTB phases for both rigid and flexible banana-shaped molecules17–20. Flexibility also plays an important role in the stabilisation of NTB phases as most rigid bent-core molecules form smectic (Sm) phases instead of nematic phases. Finally, the prediction of the surprisingly short pitch length and of the non-trivial tilt angle of the helicoidal nematic director field on the basis of the microscopic details of the particles is also of urgent interest for the design of optoelectronic materials.

On the other hand, even though the Oseen–Frank theory predicts the NSB to be more stable than the NTB phase when the splay elastic constant is smaller than twice the twist elastic constant, experimental evidence of a NSB phase is still lacking. Recent simulations suggest that an NSB phase could be stabilised in lyotropic systems of banana-shaped particles20 but the presence of long-ranged density modulations questions the nematic nature of this NSB phase. We also note that a transition from an NTB phase to an unidentified density-modulated (SmX) phase was recently observed in experiments21. Yet it is unclear what the physical mechanism is behind the NSB phase and how the system transforms into an NSB phase. Does the transformation from the N or NTB phase proceed via a first-order or second-order phase transition? Here we conjecture that the transition from the NTB to the NSB phase may proceed via an intermediate phase that displays spatial modulations of both twist, splay, and bend, thereby extending Meyer’s speculations of 1976 by conjecturing that spontaneous bend deformations of the nematic director field can be accompanied by simultaneous deformations of both twist and splay. In this picture, twist deformations in the NTB phase are gradually replaced by splay deformations, eventually resulting into an NSB phase with pure splay and bend deformations. A similar scenario was recently discovered by studying the response of an NTB phase to an external field22,23, which undergoes a structural change via an elliptical analogue of the NTB phase to an NSB phase upon increasing the field strength. This intermediate phase that we term the twist-splay-bend nematic (NTSB) phase is characterized by a nematic director that precesses around an elliptical cone with conical angles θa and θb, see Fig. 2.

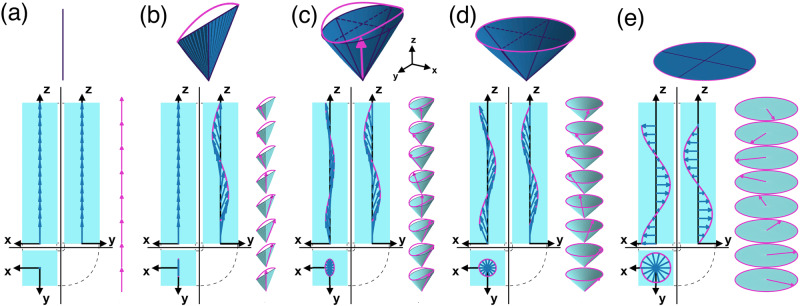

Nematic director field of a twist-splay-bend nematic phase.

Precession cone (top panel) and orthogonal projection of the nematic director field

To shed light on the microscopic origin of the spatially modulated nematic phases and to better understand the transformation from the NTB to an NSB phase via a possible NTSB phase, we develop a Maier–Saupe-like mean-field theory that takes into account not only the particle shape and interactions, but also the spatial modulations of the nematic director and density field in a variational fashion. We map out a theoretical phase diagram of curved spherocylinders that displays stable NTB, twist-splay-bend, and splay-bend phases, and test the predictions against simulations. We show that the twist-splay-bend and splay-bend (smectic) phases present periodic density modulations due to non-uniform deformations in the director field. Finally, we derive a relation between the particle curvature and the structure of the NTB phase.

Results

A variational mean-field theory for spatially modulated liquid crystal phases

We generalize a recent Maier–Saupe theory for thermotropic bent-core mesogens24 to determine the phase behavior of curved spherocylinders with diameter D, length L, and radius of curvature R corresponding to a central angle Ψ = L/R (Fig. 1d). We describe a curved spherocylinder with centre-of-mass position R = (X, Y, Z) and orientation Ω = (α, β, γ) as a rigid chain of M segments of length L/M. We find that M = 10 segments is sufficient to account for the particle shape for the range of Ψ that we considered. Each segment i, with centre-of-mass position ri and orientation

As a variational ansatz for

We note that the NTSB phase reduces to an NTB phase with a circular precession cone when θa = θb = θ0, whereas for θa = θb = π/2 the circular cone reduces to a flat circle resulting into an N* phase as the precession of the nematic director reduces to a simple twist around the phase director. If either θa or θb vanishes, the elliptical cone collapses onto a flat isosceles triangle and an NSB phase is obtained with nematic director field

As βU(R, Ω) only depends on the Z-component of R with period p, we restrict all integrations over R to integrations over Z ∈ [0, p]. The onset of orientational and/or positional order corresponds to a change of entropy per particle

Minimizing ΔF with respect to S, τ, λ, and the variational parameters θa, θb, and q of the nematic director field

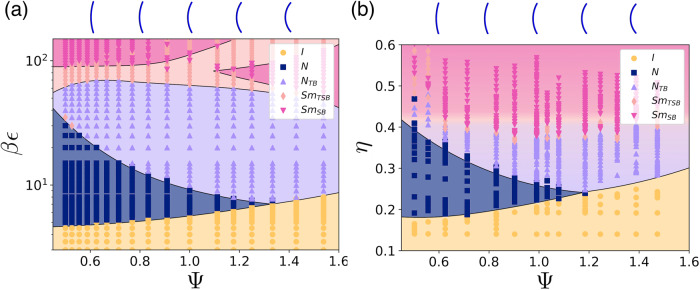

In Fig. 3a we show the resulting phase diagram from Maier–Saupe theory for a system of curved spherocylinders as a function of Ψ and inverse temperature βϵ, where we set α = 0.05. At low curvature, i.e. small Ψ, the I phase transforms into a uniaxial N phase and subsequently into an NTB phase upon increasing βϵ. However, the stability range of the N phase shrinks with increasing particle curvature, eventually disappearing at Ψ ≳ 1.2. Our results show that deformations of the nematic director field become more pronounced with increasing particle curvature Ψ until the I-N phase transition is replaced by a direct I-NTB transition20,24,26.

Phase diagram of curved spherocylinders.

Phase behaviour of hard curved spherocylinders as (a) predicted by theory, as a function of inverse temperature βϵ and particle curvature Ψ, and (b) obtained from simulations, as a function of packing fraction η and Ψ. Both phase diagrams exhibit an isotropic (I) phase at low βϵ and η, respectively. For small particle curvatures Ψ the I phase transitions into an uniaxial nematic (N) phase upon increasing βϵ or η. The stability range of the N phase decreases with Ψ and disappears at Ψ ≳ 1.2. Upon increasing βϵ or η further, the twist-bend nematic (NTB) phase transforms into a twist-splay-bend smectic (SmTSB) phase, and eventually into a splay-bend smectic (SmSB) phase. The splay deformations in the nematic director field are accompanied by density modulations. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Moreover, our generalized Maier–Saupe theory predicts that upon increasing βϵ further, the nematic director field exhibits not only twist and bend modulations but also splay deformations, resulting in a twist-splay-bend phase. Upon lowering the temperature further, the twist deformations are gradually replaced by splay deformations, eventually yielding a splay-bend phase at sufficiently high βϵ. In particular, we find two distinct regions of splay-bend phases, one at low particle curvature and one at high curvature, the latter transforming into a re-entrant twist-splay-bend phase with increasing βϵ. Intriguingly, our theory predicts that the onset of splay deformations is accompanied by density modulations. We therefore refer to these phases as twist-splay-bend smectic (SmTSB) and splay-bend smectic (SmSB) phases rather than NTSB and NSB phases. This finding is also supported by the observation that in the case of α = 0, i.e. without McMillan’s extension to describe density modulations, the phase diagram displays only stable I, N, and NTB phases. The NSB phase is thus unstable in the case of a homogeneous density field. Furthermore, we find that varying the value of α > 0 results only in a temperature shift of the transition from NTB to the SmTSB and SmSB phase, whereas the amplitude of the density modulations remains unaffected. This confirms that splay deformations of the nematic director field are inherently associated with the appearance of density modulations, as already speculated by De Gennes and Meyer, four decades ago27,28.

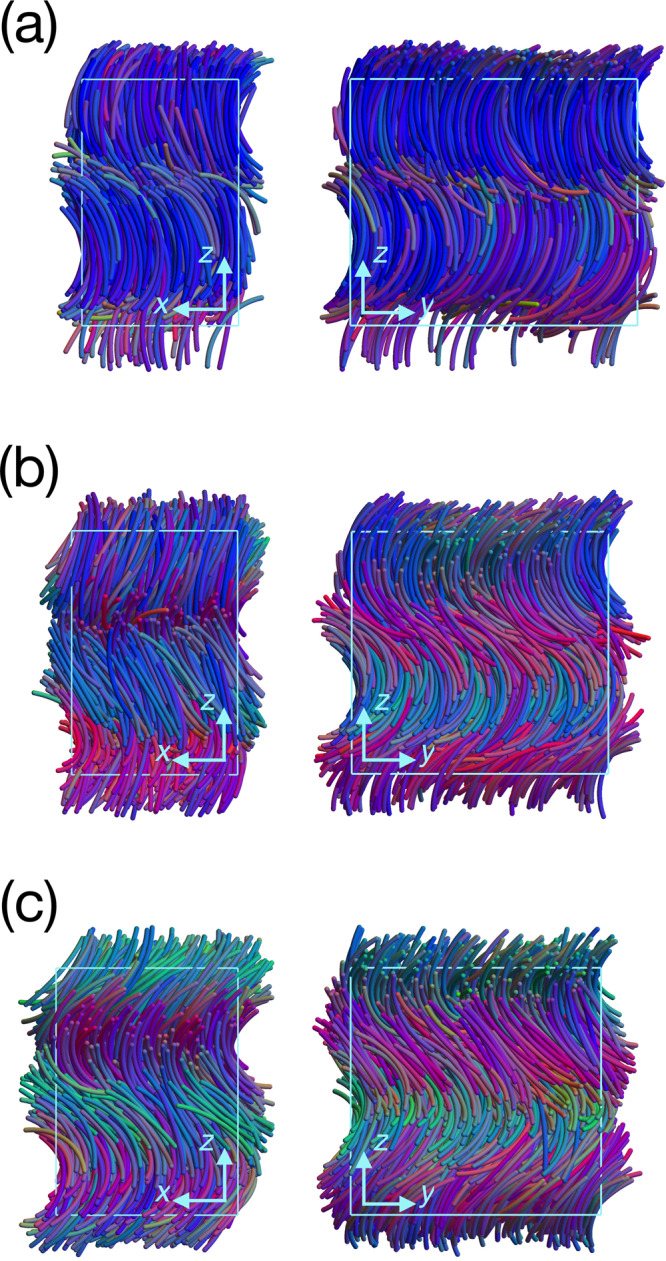

Monte Carlo simulations of hard curved spherocylinders in bulk and sedimentation

To test the predictions of our Maier–Saupe theory, we study the bulk phase behavior of hard curved spherocylinders with L/D = 19 and varying particle curvature Ψ using NPT-MC simulations, i.e. the number of particles N, pressure P and temperature T are fixed. The resulting phase diagram is shown in Fig. 3b as a function of Ψ and packing fraction η. The phase behavior of this athermal lyotropic system is driven by η that plays a similar role as the inverse temperature βϵ in our Maier–Saupe theory for thermotropic systems. Using this analogy, the comparison of the topology of the theoretical with the computational phase diagram is remarkable. Our simulations confirm the I-N-NTB phase sequence at low particle curvature that transforms into SmTSB and SmSB phases upon increasing η, as well as a direct I-NTB transition at high particle curvature transforming into SmTSB and SmSB phases with increasing density. Our simulations reveal that the splay modulations are accompanied by density modulations in agreement with our predictions from Maier–Saupe theory. In the Supplementary Note 4, we present a mapping of the theoretical and computational phase diagrams using the dependence of the global nematic order parameter Sg on temperature and packing fraction, and we provide a comparison of the orientational order parameters, pitch and conical angles as a function of thermodynamic state, showing quantitative agreement between the predictions of the Maier–Saupe theory and simulations. We note that the main qualitative difference is the absence of the re-entrant SmTSB phase in the simulated phase diagram. It is important to mention here that due to hysteresis effects and slow equilibration it is impossible to accurately determine the regions of stability and the first- or second-order nature of the phase transitions of the NTB, SmTSB, and SmSB phases in simulations of hard curved spherocylinders. However, the simulations consistently show that the phase transformation from an NTB to an SmSB phase proceeds via an intermediate SmTSB phase as twist deformations are gradually replaced by splay deformations of the nematic director field. For example, in Fig. 4 we show typical configurations of an SmSB phase, an SmTSB phase, and an NTB phase along an expansion of a system of hard curved spherocylinders of length L/D = 19 and opening angle Ψ = 1.31 from packing fraction η = 0.406 to packing fraction η = 0.367. To fully characterise the phases in Fig. 4, we plot the scalar order parameter S(z), the nematic director field

Splay-bend smectic SmSB, twist-splay-bend smectic SmTSB, and twist-bend nematic NTB phases.

Typical configurations of (a) an SmSB phase with conical angles θa ~ 0.76 and θb ~ 0 at packing fraction η = 0.394 (box size 55.5D × 30.3D × 47.7D), b an SmTSB phase with conical angles θa ~ 0.87 and θb ~ 0.51 at packing fraction η = 0.371 (box size 52.0D × 33.4D × 49.1D), and (c) an NTB phase with conical angles θa ~ θb ~ 0.83 at packing fraction η = 0.354 (box size 49.9D. 3D × 49.3D) along an expansion of a system of hard curved spherocylinders of length L/D = 19 and opening angle Ψ = 1.31.

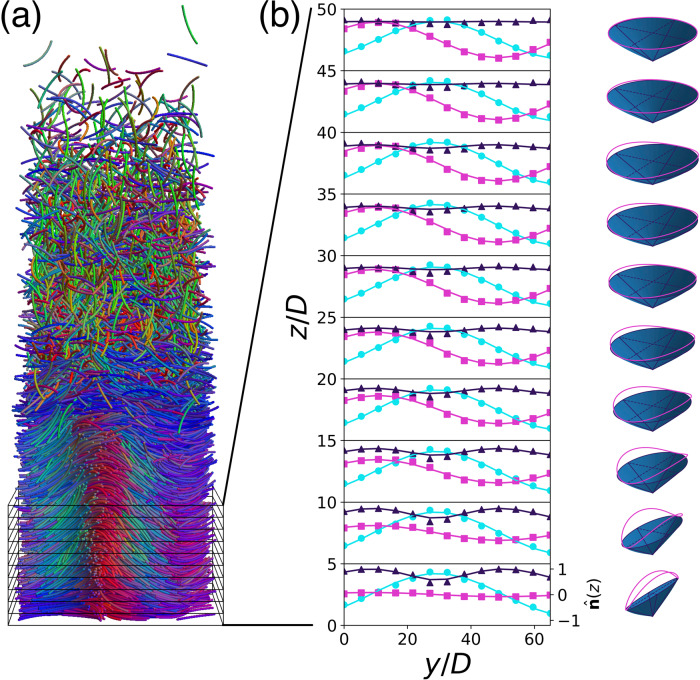

Finally, we perform simulations on a system of hard curved spherocylinders with L/D = 19 and Ψ = 0.99 under gravity with a gravitational length lg = kBT/mg = 7.5D parallel to

A system of curved rods in gravity.

a Typical configuration from a simulation on a system of hard curved spherocylinders with an aspect ratio L/D = 19 and central angle Ψ = 0.99 in a gravitational field along

Rationalising the topology of modulated liquid crystal phases

Our extensive simulations show that our generalized Maier–Saupe theory effectively predicts, despite its simplicity, the stability of twist-bend, twist-splay-bend, and splay-bend phases of curved spherocylinders. Our microscopic theory is solely based on the tendency of particles to align their particle shape to the local nematic director field

For a generic twist-splay-bend (TSB) phase the integral in Eq. (5) cannot be evaluated analytically. However, the tendency of particles to align their profiles to the nematic director field at low temperatures or high densities, corresponds to a tendency to match their particle curvature with the curvature of its integral curves. Given a curve r(z) with tangent

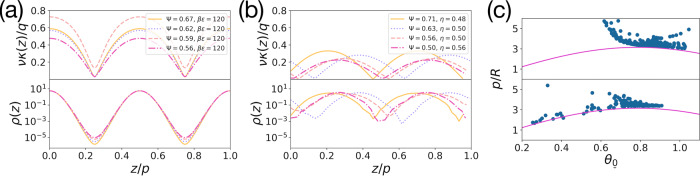

In the presence of splay deformations, i.e. θa ≠ θb, κTSB(z) is a non-trivial periodic function of z. In Fig. 6a–b, we show the curvature κSB(z) of the integral curves of the nematic director field of various splay-bend (SB) phases with θa = θ0 and θb = 0 from theory and simulations, along with their density profiles ρ(z), measuring the probability of finding a particle at z. The periodicity of κSB(z) agrees well with that of

Rationalization of the spatial modulations of the density and the nematic director fields.

a–b Modulations of the curvature κ(z) of the integral curves of the nematic director field (top), and of the logarithm of the density profile ρ(z) (bottom) corresponding to minus the effective potential acting on the particles, in splay-bend smectic states (SmSB) predicted by our theory (a) and found in Monte Carlo simulations (b) for a system of hard curved spherocylinders of various curvatures Ψ and inverse temperatures βϵ or packing fractions η as labelled. c Pitch length p versus the conical angle θ0 of various twist-bend nematic (NTB) phases of hard curved spherocylinders of various curvatures Ψ ∈ [0.5, 2] from theory (top) and simulations (bottom), along with the relationship of Eq. (7) (pink line). Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

On the other hand, in the case of an NTB phase the translational symmetry of the elastic deformations is preserved, see Supplementary Note 2, and we expect the curvature of the integral curves of the nematic director field to be uniform. Intriguingly, for NTB phases with θa = θb = θ0 the integration of Eq. (5) can be carried out explicitly, yielding the following expression

Discussion

We introduce a generic nematic NTSB phase with twist, splay, and bend modulations in the director field which reduces to N, N*, NTB, and NSB phases in limiting cases. We use the nematic director field of this NTSB phase as a variational ansatz to develop a simple but comprehensive variational Maier–Saupe theory of periodically deformed nematic and smectic phases. We exploit this mean-field theory to predict the phase behavior of curved rods as a function of thermodynamic state and microscopic details, and find excellent agreement with simulations on hard curved spherocylinders. To characterise the symmetry and local structure of these modulated phases, we measure the scalar order parameter S(z), nematic director field

Moreover, the agreement between the phase diagram determined by our simple mean-field theory for a thermotropic system and the one obtained from simulations for a lyotropic system, not only demonstrates the predictive power of our simple variational Maier–Saupe theory, but also provides strong evidence that the particle curvature is the driving force behind the topology of the spatial director-field modulations in the NTB, SmTSB, and SmSB phases. To rationalize this finding, we calculate the integral curves of the nematic director field. We show that the curvature of these integral curves is periodic in the case of SmTSB and SmSB phases, and that the coupling of particle curvature to the non-uniform curvature of the director field leads to periodic density modulations. In the case of NTB phases, we derive an explicit expression for the uniform curvature of the nematic director field integral curves. By matching this curvature with that of the particles, we derive a simple relationship between the pitch and conical angle of the NTB phase and the microscopic particle curvature. We verify this simple relationship using theory and simulations.

In conclusion, our variational ansatz for a twist-splay-bend phase is a powerful tool for predicting, understanding and rationalising spatially modulated liquid crystal phases. Exploiting the generality of this variational ansatz in a generalized Maier–Saupe theory enabled us to predict not only the stability of twist-bend and splay-bend phases, but also the orientational order parameters, pitch and conical angle as a function of the thermodynamic state and microscopic details of the particles, see Supplementary Note 5. This variational ansatz can also be exploited in Landau–de Gennes and Oseen–Frank theories of spatially modulated phases. Further improvements of the Maier–Saupe theory such as introducing biaxiality31, extending the description from prolate to oblate liquid crystals, or generalizing the variational ansatz for spatial modulations from 1D to 2D and 3D to describe polar blue phases32, may lead to a generic theoretical framework of modulated liquid crystal phases.

Methods

Variational Maier–Saupe theory

To solve our generalized Maier–Saupe theory, we minimize the free energy in Eq. (4) with respect to the variational parameters of the director- and density-field. Calculating the free-energy difference per particle βΔF/N is trivial except for the partition function Q, i.e. an integral of the form

Using the approximation of Eq. (10) and

Once Q is calculated, we minimize βΔF/N at given βϵ in the 6-dimensional space of parameters S, τ, n, θa, θb and q = 2π/p by means of a Covariance Matrix Adaptation Evolution Strategy (CMA-ES) using the Python library in https://pypi.org/project/cma/.

Monte Carlo simulations

We study the phase behavior of a system consisting of hard curved spherocylinders using Monte Carlo simulations in the NPT ensemble, i.e. at fixed number of particles N, pressure P and temperature T. We employ an orthorhombic simulation box of sides Lx, Ly, and Lz and apply periodic boundary conditions. We perform a sequence of MC cycles consisting of N + 1 MC moves. Each MC move consists of a particle move with probability ~N/(N + 1), and a volume move with probability ~1/(N + 1). In a particle move, a random roto-translation of a randomly picked particle is proposed and accepted if it does not generate overlaps with other particles. In a volume move, a random variation of a random side of the simulation box is proposed, and the system is compressed or expanded accordingly. If the compression/expansion does not generate overlaps between the particles, the move is accepted with a probability

To study a system of hard curved spherocylinders in a gravitational field, we perform Monte Carlo simulations in an NVT ensemble, i.e. we fix the number of particles N = 8192, volume V, and temperature T. We implement a hard wall at the bottom at z = 0 and apply periodic boundary conditions in the x − and y − direction. Each MC cycle consists of N attempts to randomly rotate and translate a randomly selected particle. If a particle roto-translation leads to an overlap with one of the particles or with the hard wall, the move is rejected, otherwise it is accepted with a probability

Source data

Unsupported media format: /dataresources/secured/content-1766050081059-e6850f23-aa55-4fc1-ae41-ec990195375b/assets/41467_2021_22413_MOESM3_ESM.zip

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41467-021-22413-8.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge financial support from the EU H2020-MSCA-ITN- 2015 project ‘MULTIMAT’ (Marie Sklodowska-Curie Innovative Training Networks) [project number: 676045].

Author contributions

M.D. initiated this work on the phase behavior of curved rods and supervised M.C. M.C. generalized the Maier–Saupe theory to curved rods and performed the theoretical calculations and the computer simulations on hard curved spherocylinders. M.C. and M.D. analysed and discussed the results, and co-wrote the paper.

Data availability

The source data from Figs. 3, 5b, 6, Supplementary Figs. 1, 2, 3, 7, 8, 9, 11, 12, 13, 14, and 15 are provided in the source data file. All the other relevant data associated with this research is available upon request. Source data are provided with this paper.

Code availability

The simulation and analysis codes associated with this research are available upon request.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

References

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

6.

7.

8.

9.

10.

11.

12.

13.

14.

15.

16.

17.

18.

19.

20.

21.

22.

23.

24.

25.

26.

27.

28.

29.

30.

31.

32.

A generalized density-modulated twist-splay-bend phase of banana-shaped particles

A generalized density-modulated twist-splay-bend phase of banana-shaped particles