- Altmetric

Controlling the reactivity of reactive intermediates is essential to achieve selective transformations. Due to the facile 1,5-hydrogen atom transfer (HAT), alkoxyl radicals have been proven to be important synthetic intermediates for the δ-functionalization of alcohols. Herein, we disclose a strategy to inhibit 1,5-HAT by introducing a silyl group into the α-position of alkoxyl radicals. The efficient radical 1,2-silyl transfer (SiT) allows us to make various α-functionalized products from alcohol substrates. Compared with the direct generation of α-carbon radicals from oxidation of α-C-H bond of alcohols, the 1,2-SiT strategy distinguishes itself by the generation of alkoxyl radicals, the tolerance of many functional groups, such as intramolecular hydroxyl groups and C-H bonds next to oxygen atoms, and the use of silyl alcohols as limiting reagents.

The generation of α-carbon radicals from alkoxyl radicals is challenging because 1,2-hydrogen atom transfer (HAT) is usually less favoured than 1,5-HAT. Here, the authors report a strategy to inhibit 1,5-HAT by introducing a silyl group into the α-position of alkoxyl radicals, enabling preparation of α-alkoxylimino alcohols and α-heteroaryl alcohols.

Introduction

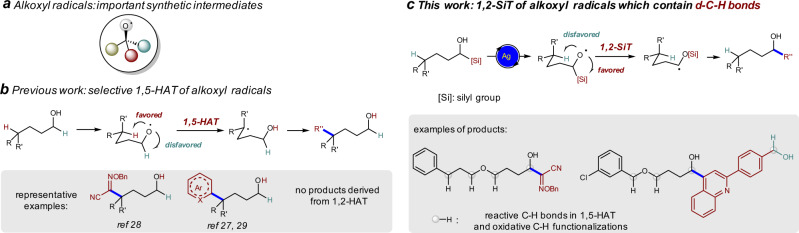

Radicals, anions, cations, carbenes, and others are key reactive intermediates in synthesis1. These intermediates usually show different reactivity, facilitating the development of complementary methodologies for the synthesis of molecules that are important in material and/or life-related field2–4. Among various radicals, alkoxyl radicals have gained increasing attention (Fig. 1a)5–9. Although the previous studies to generate alkoxyl radicals usually need pre-activated alcohols or corresponding precursors10–21, recent work on the direct activation of alcohols with photocatalysis and/or transition-metal catalysis largely broaden their synthetic utility22–29. When δ-C–H bonds are present, the intramolecular 1,5-hydrogen atom transfer (HAT) from the δ-position via a low-energy six-membered ring transition state is usually favored over the transfer of hydrogen atoms at other positions, thus alkoxyl radical-mediated δ-C–H functionalization is widely studied (Fig. 1b)6. For example, the synthesis of δ-alkoxylimino alcohols and intermolecular δ-heteroarylation of alcohols through 1,5-HAT of alkoxyl radicals have been achieved (Fig. 1b)27–29. However, alkoxyl radical-mediated α-functionalization of alcohols have not been reported30,31. It is also known that excess amount of alcohols are usually required in oxidative C–H functionalization reactions, and it is challenging to control the selectivity when multiple oxidizable C–H bonds are present in the substrate30,31. Silicon possesses empty d orbitals and C–Si bond is longer than C–H bond. We envisioned that 1,2-silyl transfer (SiT) of alkoxyl radical via three-membered ring transition state (also known as radical Brook rearrangement, RBR) might be easier than the corresponding 1,2-HAT and might be favored over 1,5-HAT process (Fig. 1c).

Tuning the reactivity of alkoxyl radicals from 1,5-HAT to 1,2-SiT by the incorporation of a silyl group.

a Alkoxyl radicals are important synthetic intermediates. b Intramolecular 1,5-hydrogen atom transfer (HAT) via a six-membered ring transition state is usually favored over the transfer of hydrogen atoms at other positions, thus alkoxyl radicals mediated δ-C–H functionalization is widely studied. c We disclose here that 1,2-silyl transfer (SiT) is favored over 1,5-HAT under Ag-catalyzed conditions, allowing the efficient synthesis of α-hydroxyl oxime ethers and α-heteroaryl alcohols (this work). The alkoxyl radical-mediated reactions can tolerate many reactive C–H bonds, which are reactive in 1,5-HAT and oxidative C–H functionalizations. Another OH group in the substrates can also be tolerated.

RBR was initially proposed to explain the cyclopropanation product of the photoreaction between acylsilanes and electron-poor olefins in 198132–35. However, the synthetic application of RBR was nearly ignored in the following decades35–38. Until 2017, Smith and group found that benzylic radicals can be generated from the oxidation of hypervalent silicate intermediate by a photo-excited Ir complex37. In 2020, our group revealed that the Mn-catalyzed RBR is superior to anion Brook rearrangement in the direct trifluoroethanol transfer reactions38. Herein, we show that radical 1,2-SiT is favored over 1,5-HAT under Ag-catalysis conditions, and selective α-C–C bond formation reactions are achieved without any δ-functionalization product, in which the use of alcohols as limiting reagents in the reaction of oxime ethers and the tolerance of various C–H bonds and benzyl alcohols demonstrate the synthetic potential of our methodology (Fig. 1c)30,31.

Results

Radical 1,2-SiT in the synthesis of α-hydroxyl oxime ethers

Oximes and oxime ethers are important synthetic building blocks, and they have also been found to be core structural motifs of multiple bioactive molecules28,39–41. In 2018, Jiao and co-workers reported the synthesis of δ-alkoxylimino alcohols through 1,5-HAT of alkoxyl radicals, but no α-alkoxylimino alcohols were isolated28. Previous methods to prepare α-hydroxyl oxime ethers mainly rely on the reduction of alkoxyliminyl substituted ketones, which themselves need multistep synthesis41. To the best of our knowledge, there is no report on radical-mediated synthesis of α-alkoxylimino alcohols. Therefore, we choose to investigate the reaction between α-silyl alcohol 1a and sulfonyl oxime ether 2 to check whether α-functionalization product or δ-functionalization product can be obtained.

Optimization of the reaction conditions for the synthesis of α-hydroxyl oxime ethers

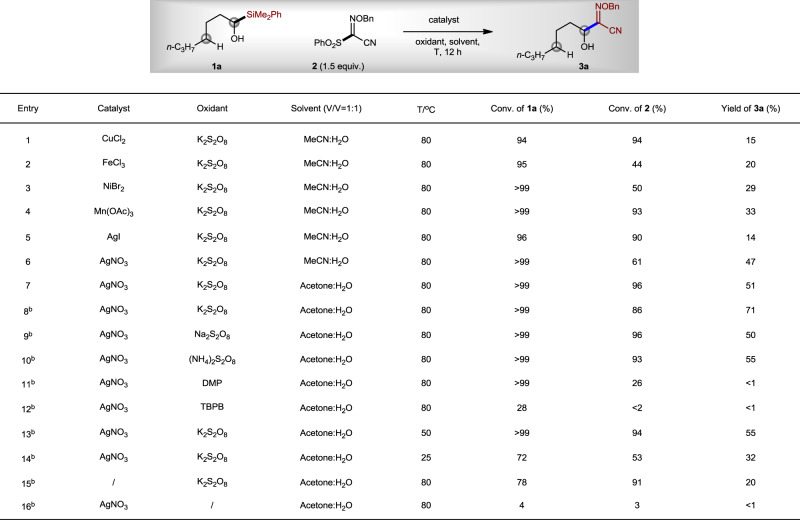

Previously, we found the Mn(II)/Mn(III)-catalyzed metal alkoxide (M-OR) homo-cleavage strategy was an efficient way to generate alkoxyl radicals for the direct transfer of trifluoroethanol and difluoroethanol units38. Therefore, we focused on the investigation of various transition-metal salts for M-OR homo-cleavage. After extensive investigations, we found that AgNO3 was a better pre-catalyst than CuCl2, FeCl3, NiBr2, Mn(OAc)3, and AgI (Fig. 2, entries 1–6). When the reaction was carried out in MeCN/H2O (v/v = 1:1) at 80 °C for 12 h with K2S2O8 as an oxidant, a yield of 47% was afforded for compound 3a, without any detection of δ-functionalization product (entry 6). When the solvent was changed to acetone/H2O (v/v = 1:1), the yield of α-functionalization product 3a increased to 51% (entry 7). Increasing the concentration of the reaction resulted in an improved yield of compound 3a (71%, entry 8). Other oxidants such as Na2S2O8, (NH4)2S2O8, Dess–Martin periodinane, and tert-butyl peroxybenzoate afforded lower efficiency of the reaction (entries 9–12). Lowering the reaction temperature also resulted in a decreased yield of compound 3a (entries 13 and 14). The control experiment showed that, without AgNO3, only 20% yield of compound 3a was observed by proton nuclear magnetic resonance, although a large amount of decomposition of compounds 1a and 2 (entry 15) were found. However, no 3a was generated without K2S2O8, and the conversions of compounds 1a and 2 were also low, indicating that AgNO3 alone cannot catalyze the reaction (entry 16).

Reaction optimization.

aThe mixture of 1a (0.2 mmol), catalyst (0.04 mmol), oxidant (0.4 mmol), and 2 (0.3 mmol) in the solvent (2 mL) was stirred at T under N2 for 12 h. Conversions of 1a and 2 and yield of 3a were determined by 1H NMR using BrCH2CH2Br as an internal standard. bSolvent (1.5 mL). DMP Dess–Martin periodinane, TBPB tert-butyl peroxybenzoate.

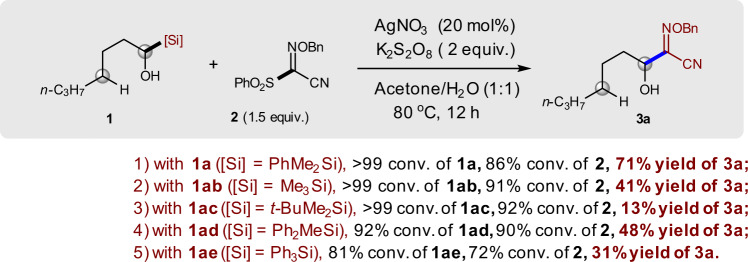

Influence of silyl groups on the efficiency of the reaction

Encouraged by the favored α-functionalization over δ-functionalization in the reaction between compounds 1a and 2, we then investigated the influence of the silyl substituent on the efficiency of the desired α-functionalization reaction. It was found that both electronic property and steric hindrance of the silyl group showed a significant effect on our reaction. The electron-withdrawing effect of the phenyl group on the silicon atom appears to play a positive role in this reaction (Fig. 3). However, the steric hindrance on the silicon atom shows a negative effect in this reaction (1a vs 1ad and 1ae; 1ab vs 1ac). In all cases, aldehyde derived from compound 1 was formed as by-product. The substituents might not only affect the transfer ability of the silyl group but also affect the stability and reactivity of the radical intermediate III (see below). Moreover, the different substituents of the silyl groups also affect the C–Si bond length and bond dissociation energy, which might also be important factors in 1,2-SiT. Again, none of the reactions afforded δ-functionalization product.

Influence of silyl groups on the efficiency of the reaction.

Reaction conditions: the mixture of 1 (0.2 mmol), AgNO3 (0.04 mmol), K2S2O8 (0.4 mmol), 2 (0.3 mmol), and acetone/H2O (0.75 mL/0.75 mL) was stirred at 80 °C under N2 for 12 h. Conversion of 1 and 2 and yield of 3a were determined by 1H NMR using BrCH2CH2Br as an internal standard.

Mechanism study

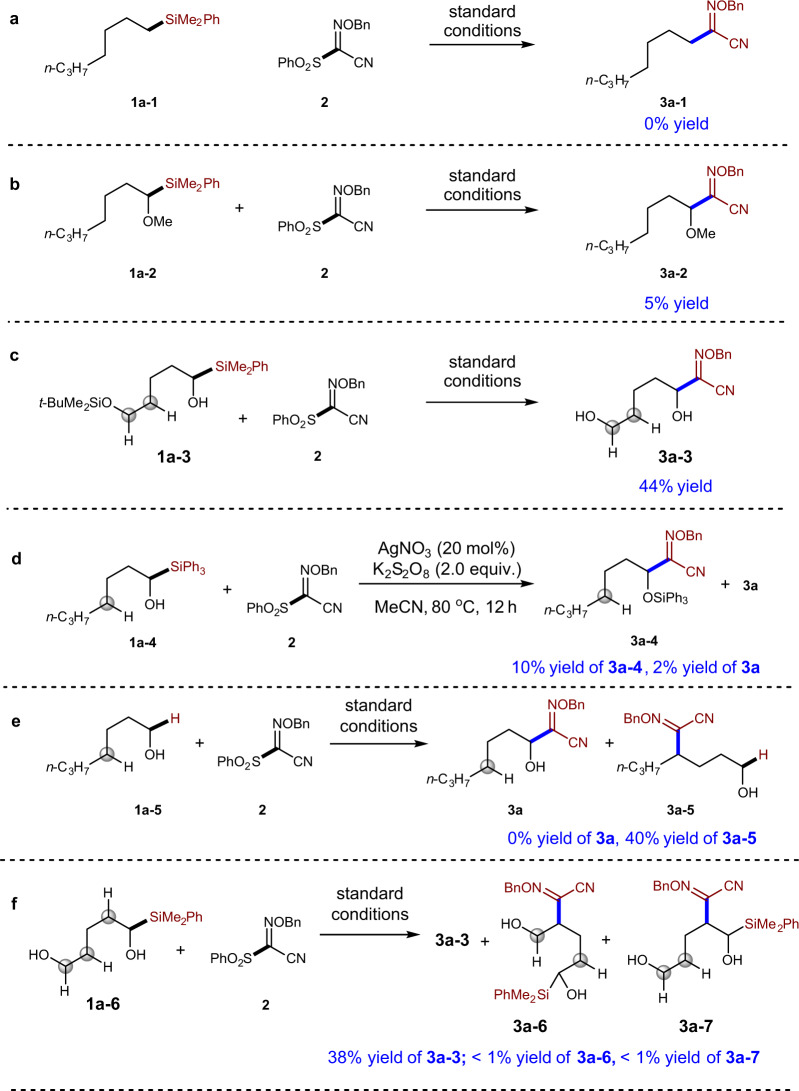

After identification of a suitable silyl group to promote the efficient synthesis of α-alkoxylimino alcohol 3a, we set to investigate whether the reaction proceeded through radical 1,2-SiT or not. Firstly, our study reveals that the OH group is important for the success of the reaction. The use of compound 1a-1 as starting material resulted in no anticipated product 3a-1 (Fig. 4a). Protected α-silyl alcohol 1a-2 only gave 5% yield of compound 3a-2 (Fig. 4b), indicating that the generation of carbon radical via direct oxidative cleavage of C–Si bond is less likely to be the major pathway in the reaction with 1a42–45. This result was consistent to the similar oxidation potential of α-silyl alcohol and the methyl-protected counterpart46. When silyl ether compound 1a-3 was applied in the reaction with compound 2, free diol 3a-3 was obtained in 44% yield (Fig. 4c), suggesting that silyl ether can be hydrolyzed under aqueous reaction condition. Further study of the reaction of triphenylsilyl-substituted alcohol 1a-4 with compound 2 under no H2O condition showed that compound 3a-4 could be synthesized in 10% yield with 2% yield of desilylated compound 3a (Fig. 4d). The lower yield of 3a-4 and 3a might be explained by the low solubility under the non-aqueous conditions (Fig. 4d). Jiao and co-workers have shown that alcohols can participate in δ-functionalization via radical 1,5-HAT under Ag catalysis28. The reaction of non-silylated alcohol 1a-5 indeed afforded 1,5-HAT product 3a-5 in 40% yield without the formation of ɑ-functionalization product 3a (Fig. 4e). Interestingly, when a silyl alcohol 1a-6, which contains another C–OH bond, was tested in the reaction with compound 2, the major product is C–Si bond functionalization product 3a-3 (38% yield; Fig. 4f), further indicating radical 1,2-SiT is favored over 1,5-HAT. The tolerance of free alcohol is an advantage of our method, since diols are challenging substrates for the oxidative C–H bond functionalization chemistry30,31.

Mechanistic studies.

a Failure of the reaction with heptyldimethyl(phenyl)silane 1a-1 indictates the importance of OH group in the success of the reactions. b Failure of the reaction of protected α-silyl alcohol 1a-2 indicates that direct oxidative cleavage of C–Si bond is less likely. c Reaction 1a-3 shows that silyl ether group could be hydrolyzed under the reaction conditions. d Reaction of α-triphenylsilyl alcohol 1a-4 under conditions without H2O could afford non-desilylated product 3a-4. e The reaction of non-silylated alcohol 1a-5 indeed afforded 1,5-HAT product 3a-5 without the formation of ɑ-functionalization product 3a. f Remote OH group in 1a-6 can be tolerated.

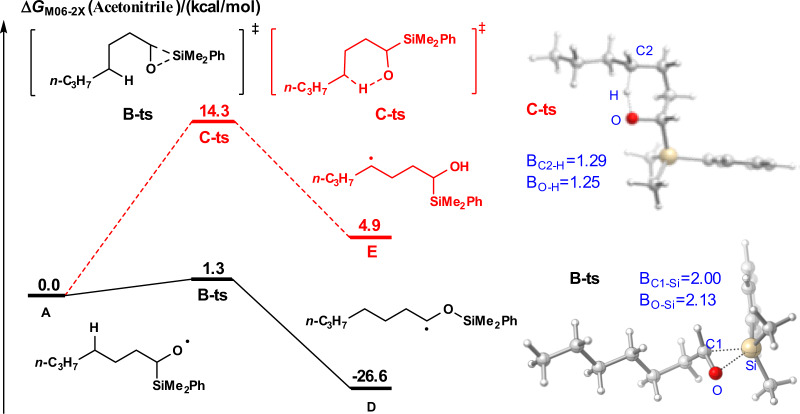

Subsequently, we investigated the energy barrier of 1,2-SiT and 1,5-HAT of alkoxyl radical intermediate A using density functional theory (DFT) calculation employing the method M06-2X (for details, see the Supplementary information 3i–n)47–49. As shown in Fig. 5, alkoxyl radical A was set as the starting point for the free-energy profiles. 1,2-SiT via transition state B-ts to generate radical intermediate D is quite easy with an energy barrier of only 1.3 kcal/mol, and this process is exothermic (26.6 kcal/mol). However, 1,5-HAT via transition state C-ts to generate radical intermediate E is an endothermic reaction (4.9 kcal/mol) with an energy barrier of 14.3 kcal/mol. The calculation results show that 1,2-SiT process of radical A is both dynamically and thermodynamically favored over the corresponding 1,5-HAT.

Free-energy profile of the pathways for 1,2-SiT vs 1,5-HAT.

The energies are in kcal/mol and represent the relative free energies calculated with the DFT/M06-2X method in MeCN. The bond distances are in angstroms.

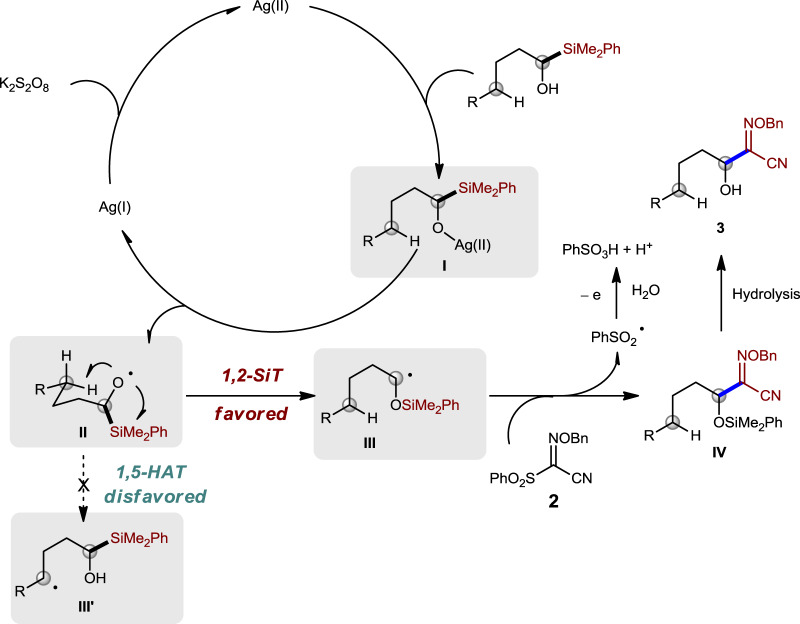

Based on our experimental DFT calculation results and previous reports28, a plausible mechanism involving 1,2-SiT was proposed in Fig. 6. Oxidation of Ag(I) by K2S2O8 might afford Ag(II)50, which would undergo ligand exchange with alcohol 1a and results in the generation of intermediate I. Homolysis of intermediate I could produce alkoxyl radical II and Ag(I). Carbon radical III would be generated through 1,2-SiT, which is favored over 1,5-HAT. Intermediate IV might be generated from the addition–elimination process between carbon radical III and compound 2, but we cannot rule out the possibility of its formation through trapping III with iminyl radical generated from homolysis of compound 2 (for details, see Supplementary information). PhSO2 radical might be converted to PhSO3H under the oxidation condition in the aqueous solution15. PhSO3− was detected by high-resolution mass spectrometry analysis of the reaction mixture, which supports this proposal (for details, see Supplementary information). The alcohol product 3 would be produced after desilylation under aqueous condition.

Proposed mechanism.

The proposed mechanism involves an Ag(I)/Ag(II) catalytic cycle and 1,2-SiT.

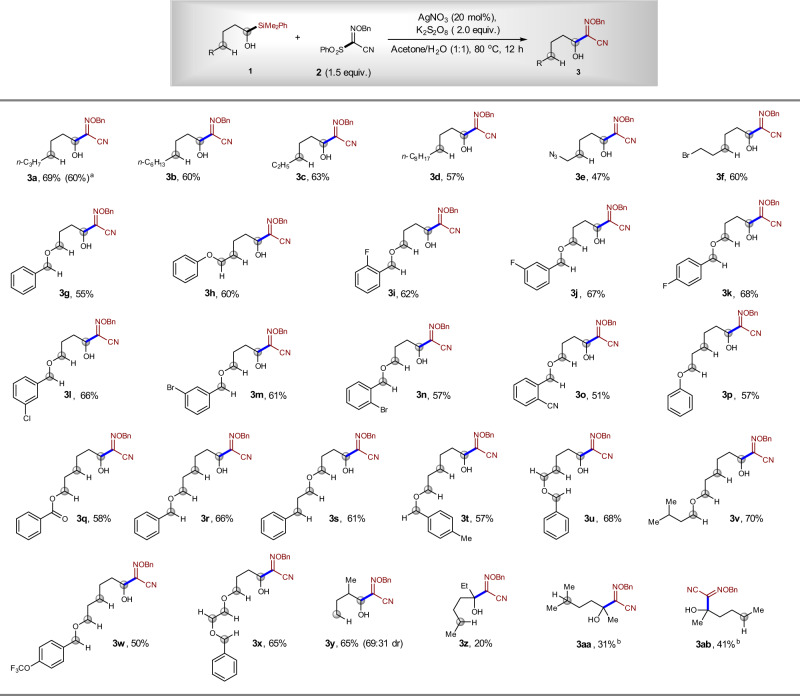

Scope of the reaction between α-silyl alcohol 1a and sulfonyl oxime ether 2

Subsequently, we investigated the scope of the radical substitution reaction between α-silyl alcohol 1 and sulfonyl oxime ether 2. The reaction showed broad substrate scope, and various α-silyl alcohols could participate in the reaction, affording corresponding α-alkoxylimino alcohols in 48–70% yields. When 1 g of 1a was employed, product 3a could be isolated in 60% yield. The reaction can tolerate many functional groups, such as C(sp3)-Br, C(sp3)-N3, C(sp2)-F, C(sp2)-Cl, C(sp2)-Br, C(sp2)-CN, C(sp2)-OCF3, and an ester group. These functional groups can be used for further transformations. When the δ-C–H bond is next to an oxygen atom, the 1,5-HAT of the alkoxyl radicals could be more favored, because the new radical can be stabilized by the oxygen through hyper-conjugation interaction30,31. However, under our reaction conditions, not only the normal δ-C–H bond can be tolerated, but the δ-C–H bond next to an oxygen atom can also be tolerated (Fig. 7, 3g, 3i–3o, 3s). Moreover, benzylic, α-oxy, and α-benzoyloxy C–H groups, which are usually reactive in oxidative C–H bond cleavage reactions, are maintained under our reaction conditions (Fig. 7, 3g–3x)30,31. In addition, our reaction can be applied in the synthesis of alcohols, which contain a β-substituent. Compound 3y was synthesized in 65% yield, which is in sharp contrast to the failure to synthesize alcohols in previous Ag-catalyzed reaction28. The relative lower yield was found for the assembly of tertiary alcohol 3z (20% yield), 3aa (31% yield), and 3ab (41% yield). In all cases, the alcohols 3 were obtained directly after the reaction, without the extra deprotection step of anticipated silyl ether intermediate IV. In all cases, the alcohol substrates were used as limiting reagents, which further highlight the synthetic potential of the current method since the oxidative α-C–H functionalization of alcohols usually need excess amount of alcohols, and in many cases, alcohols must be used as a solvent to achieve synthetic useful yield30,31.

Scope for the synthesis of α-alkoxylimino alcohols.

aThe yield in the parentheses refers to the isolated yield of the gram-scale reaction. bAcetone/H2O (v/v = 2:1) was used as the solvent.

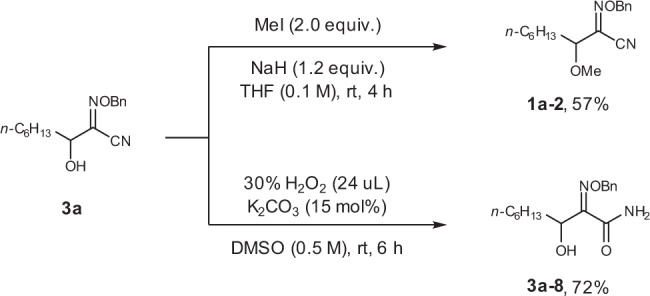

Synthetic transformations of compound 3a

Compound 3a was easily transformed to methylated product 1a-2 in 57% yield, while the imine group was untouched (Fig. 8). The CN group could be hydrolyzed in the presence of H2O2 and K2CO3, affording amide 3a-8 in 72% yield (Fig. 8).

The chemo-selective transformation of 3a.

The oxime ether product 3a could be easily converted to methylated product 1a-2 and amide 3a-8.

Radical 1,2-SiT in the catalytic Minisci reaction for the synthesis of α-heteroaryl alcohols

Heteroaryl groups are important structural motifs and Minisci reaction is one of the most atom-economic ways to introduce heteroaryl groups into organic molecules, by cleaving the C(sp2)–H bond51,52. The 1,5-HAT process of alkoxyl radicals was used by Zhu’s group and Chen’s group in the hypervalent iodine-mediated radical Minisci reaction and various δ-heteroaryl-substituted alcohols have been made27,29. To the best of our knowledge, there has been no report on Minisci type α-heteroarylation through 1,2-HAT of alkoxyl radicals. Although direct radical α-heteroarylation of alcohols was achieved by the intermolecular H abstraction, they usually need excess amount of alcohols as reagents31,51,52. In most cases, alcohols are used as the solvent, which limits the application of those methods, especially when complex alcohols are needed and/or the alcohols are solids. Encouraged by the success of the application of radical 1,2-SiT in the direct synthesis of alkoxylimino alcohols, we probed the applicability of this strategy in the catalytic Minisci reaction for the synthesis of secondary alkyl heteroaryl alcohols.

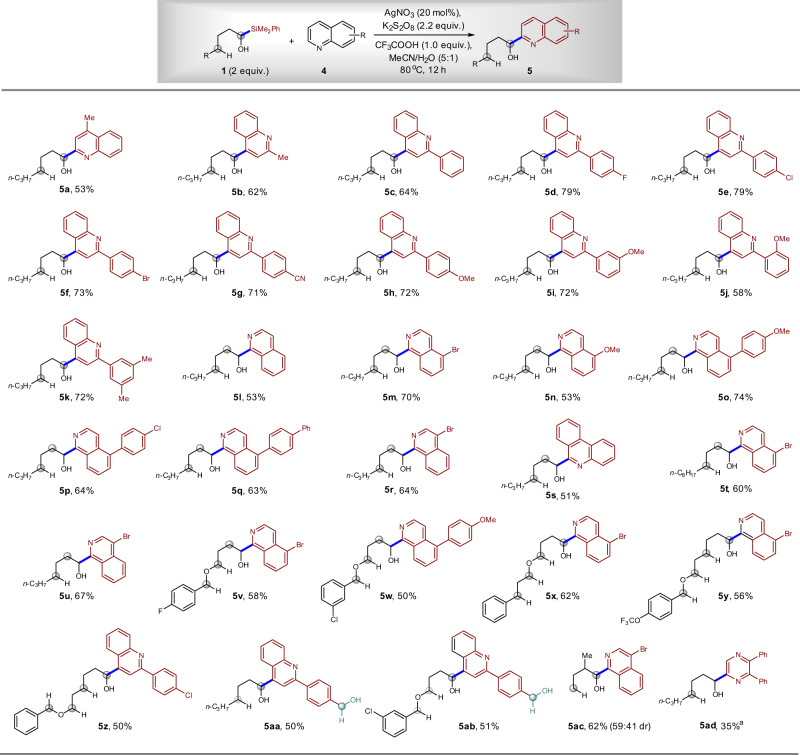

After a quick optimization of reaction conditions (for details, see Supplementary information), we found that similar Ag-catalysis conditions could be applied in the reactions between α-silyl alcohol 1 and heteroarenes 4 (Fig. 9). Quinolines with methyl and aryl substituents are competent reaction partners, delivering the desired α-heteroarylation products 5a–k in 53–79% yields. The F, Cl, Br, CN, OMe, and Me groups on the aryl substituents are tolerated. Isoquinoline derivatives such as Cl-, Br-, MeO-, and BnO-substituted isoquinolines performed well, affording products 5m–r in 53–74% yields. An α-silyl alcohol containing a long alkyl chain also works, affording compound 5r in 64% yield and 5t in 60% yield. Moreover, phenanthridine can participate in the reaction, giving corresponding alkyl heteroaryl alcohol 5s in 51% yield. One of the disadvantages of the previous direct α-heteroarylation of alcohol is the need to use excess amount of alcohol, which is formidable when the complex is applied. We found that only two equivalent of α-silyl alcohol was required in the current radical Minisci reaction, and the relatively complex alcohols 5v–z were prepared in 50–62% yields. It is worth noting that even benzyl alcohol can be tolerated (5aa, 50%; 5ab, 51%). These two compounds would be challenging to synthesize via the oxidative C–H bond functionalization methodology because the benzyl alcohol would result in trouble30,31. Moreover, the synthesis of alcohols, which contain a β-substituent, was successful and compound 5ac was synthesized in 62% yield, which is in sharp contrast to the failure to synthesize alcohols in previous Ag-catalyzed reaction28. Again, no δ-heteroarylation products were isolated in all cases shown in Fig. 9.

Scope of Minisci reaction for the synthesis of α-heteroaryl alcohols.

The reaction could tolerate various C–H bonds and benzyl alcohols that are reactive in oxidative C–H functionalization reactions. aDMSO/H2O (v/v = 5:3) was used as the solvent.

Discussion

In this work, we found that the introduction of a silyl group to the α-position of alcohols can effectively inhibit 1,5-HAT of the corresponding alkoxyl radicals. The substituents on the silicon are found to be important to achieve efficient 1,2-SiT. The carbon radicals derived from 1,2-SiT are applied in the radical substitution reactions of sulfonyl oxime ether and heteroarenes to prepare α-alkoxylimino alcohols and alkyl heteroaryl alcohols. Compared with the direct generation of α-carbon radicals from the oxidation of α-C–H bond of alcohols, the 1,2-SiT strategy distinguished itself by the generation of alkoxyl radicals, the tolerance of many functional groups such as intramolecular hydroxyl groups and C–H bonds next to oxygen atoms, and the use of silyl alcohols as limiting reagents. Our experimental finding broadens the synthetic application of alkoxyl radicals. Further application of the 1,2-SiT of alkoxyl radicals is underway in our laboratory.

Methods

Typical procedure 1 (3a)

In an Ar-protected glove box, AgNO3 (6.8 mg, 0.04 mmol, 20 mol%), 2 (90.0 mg, 0.30 mmol, 1.5 equiv.), and 1a (50.0 mg, 0.20 mmol) were added into a reaction tube. After that, the tube was taken out of the box, acetone/H2O (0.75 mL/0.75 mL) and K2S2O8 (108.0 mg, 0.40 mmol, 2.0 equiv.) were added under N2. The tube was then sealed, and the resulting mixture was kept stirring at 80 °C in a heating block for 12 h. The reaction mixture was quenched with water (5 mL), extracted with ethyl acetate (3 × 10 mL), and the organic phase was combined and washed with brine, dried over anhydrous Na2SO4, and concentrated under reduced pressure. The crude product was purified with column chromatography on silica gel (200–300 mesh) with petroleum ether/ethyl acetate (PE/EA) (8/1, v/v) as eluent to afford 38.0 mg of the title compound as a faint yellow oil (69% yield).

Typical procedure 2 (5a)

Under N2 atmosphere, AgNO3 (6.8 mg, 0.04 mmol, 20 mol%), CH3CN/H2O (1.67 mL/0.33 mL), 4a (28.6 mg, 0.20 mmol), CF3COOH (22.8 mg, 0.2 mmol, 1.0 equiv.), 1a (100 mg, 0.40 mmol, 2.0 equiv.), and K2S2O8 (118.8 mg, 0.44 mmol, 2.2 equiv.) were added into a reaction tube. The tube was then sealed, and the resulting mixture was kept stirring at 80 °C in a heating block for 12 h. The reaction mixture was quenched with saturated NaHCO3 aqueous solution (10 mL), extracted with ethyl acetate (3 × 10 mL), and the organic phase was combined and washed with brine, dried over anhydrous Na2SO4, and concentrated under reduced pressure. The crude product was purified with column chromatography on silica gel (200–300 mesh) with PE/EA (10/1, v/v) as eluent to afford 27.0 mg of the title compound as a faint yellow oil (53% yield).

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41467-021-22382-y.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to NSFC (21901191, 21822303), Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (2042018kf0023, 2042019kf0006), State Key Laboratory of Bioorganic & Natural Products Chemistry (BNPC18237), and Wuhan University for financial support. We are thankful to Prof. Aiwen Lei and Prof. Xumu Zhang at Wuhan University for the generous provision of the basic instruments.

Author contributions

X.S. designed and directed the investigations and composed the manuscript with revisions provided by the other authors. Z.Y. and Y.N. developed the catalytic method. Z.Y., Y.N., and S.C. studied the substrate scope. X.H. and Y.L. conducted the calculations. Z.Y., Y.N., X.H., S.C., S.L., Z.L., X.C., Y.Z., Y.L., and X.S. were involved in the analysis of results and discussions of the project.

Data availability

The authors declare that all other data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article and Supplementary information files, and also are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

References

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

6.

7.

8.

9.

10.

11.

12.

13.

14.

15.

16.

17.

18.

19.

20.

21.

22.

23.

24.

25.

26.

27.

28.

29.

30.

31.

32.

33.

34.

35.

36.

37.

38.

39.

40.

41.

42.

43.

44.

45.

46.

47.

48.

49.

50.

51.

52.

Tuning the reactivity of alkoxyl radicals from 1,5-hydrogen atom transfer to 1,2-silyl transfer

Tuning the reactivity of alkoxyl radicals from 1,5-hydrogen atom transfer to 1,2-silyl transfer