- Altmetric

Magnetic atoms coupled to the Cooper pairs of a superconductor induce Yu-Shiba-Rusinov states (in short Shiba states). In the presence of sufficiently strong spin-orbit coupling, the bands formed by hybridization of the Shiba states in ensembles of such atoms can support low-dimensional topological superconductivity with Majorana bound states localized on the ensembles’ edges. Yet, the role of spin-orbit coupling for the hybridization of Shiba states in dimers of magnetic atoms, the building blocks for such systems, is largely unexplored. Here, we reveal the evolution of hybridized multi-orbital Shiba states from a single Mn adatom to artificially constructed ferromagnetically and antiferromagnetically coupled Mn dimers placed on a Nb(110) surface. Upon dimer formation, the atomic Shiba orbitals split for both types of magnetic alignment. Our theoretical calculations attribute the unexpected splitting in antiferromagnetic dimers to spin-orbit coupling and broken inversion symmetry at the surface. Our observations point out the relevance of previously unconsidered factors on the formation of Shiba bands and their topological classification.

The influence of spin-orbit coupling on the hybridization of Shiba states in dimers of magnetic atoms on superconducting surfaces remains unexplored. Here, the authors reveal a splitting of atomic Shiba orbitals due to spin-orbit coupling and broken inversion symmetry in antiferromagnetically coupled Mn dimers placed on a Nb(110) surface.

Introduction

The interplay between spin–orbit coupling (SOC), magnetism, and superconductivity has been extensively studied in recent years due to their applications in quantum computation, particularly concerning the realization of topological qubits based on Majorana bound states (MBS). Evidence of MBS that can exist on the edges of topological superconductors have been reported in various systems involving strong SOC, ranging from semiconductor nanowires proximity coupled to s-wave superconductors1–4, over magnetic vortex cores in topological superconductors5,6, to one-7–11 and two-dimensional12–14 magnetic nanostructures on s-wave superconductors. Promising building blocks for the latter systems are states formed by the hybridization of Yu–Shiba–Rusinov excitations (referred to as Shiba states)15–17 which lead to the emergence of so-called Shiba bands in nanostructures. Shiba states are induced in the vicinity of magnetic impurities embedded in or adsorbed on the surface of a superconductor via a potential that locally breaks Cooper pairs. Aiming at tailoring the Shiba bands for topological superconductivity, experimental work has focused on investigations of the Shiba states of single magnetic impurities on superconducting substrates18–26 and of coupled dimers of such impurities27–30.

In dimers with spacings less than the lateral extent of the Shiba states, the bound states are expected to hybridize. As calculated in ref. 17, there is a fundamental difference between ferromagnetically (FM) and antiferromagnetically (AFM) aligned dimers. In FM dimers, the states strongly hybridize and split into a symmetric and an antisymmetric linear combination of the single-impurity Shiba states. In contrast, for AFM alignment, the hybridization is expected to be weaker since quasiparticles of opposite spin are scattered preferentially by the two impurities, which leads to a smaller shift in the Shiba state energies. Importantly, the two Shiba states remain degenerate in a perfectly AFM-aligned dimer, since exchanging the positions of the two impurities while simultaneously switching the spin directions is a symmetry of the system31–33. Experimental results have partially confirmed this picture by observing the presence and the absence of the splitting in dimers which have been identified as FM-aligned and AFM-aligned in density-functional theory calculations, respectively28. Accordingly, in the absence of information about the exchange interaction between the localized spins27,30, it was argued that the observation of the splitting of Shiba states is sufficient to exclude an AFM coupling. All of these experimental observations have been explained based on the theoretical framework formulated by Yu, Shiba, and Rusinov15–17. This theory does not take into account SOC, and its influence on the Shiba states has been considered in surprisingly few works so far34,35. Over the recent decades, a plethora of novel phenomena in solid-state physics has been demonstrated to arise due to the combination of SOC with inversion-symmetry breaking. These include the emergence of Rashba-split surface states in the electronic structure36; the mechanism of the Dzyaloshinsky–Moriya interaction37,38, which gives rise to chiral non-collinear magnetic configurations39–41; the formation of MBS in magnetic chains proximity coupled to a superconductor42; and the presence of the crystal anomalous Hall effect in collinear antiferromagnets43.

Here, we reveal a so far unconsidered mechanism of Shiba state hybridization caused by SOC in noncentrosymmetric systems. We present a scanning tunneling spectroscopy (STS) study of the multi-orbital Shiba states of single Mn adatoms and Mn dimers on Nb(110). Using the tip of a scanning tunneling microscope (STM) to artificially construct dimers, we vary interatomic orientations and spacings. We identify dimers both with FM and AFM alignments based on spin-polarized measurements. Regardless of the relative orientation of the spins, we observe shifted and split Shiba states in the Mn dimers. However, for the AFM case, the spatial distributions of their wavefunctions no longer clearly resemble the usual symmetric and antisymmetric combinations of the single-impurity Shiba states that are found for the FM case. Our theoretical calculations demonstrate that taking into account SOC and inversion-symmetry breaking is necessary for lifting the twofold degeneracy of Shiba states in AFM-oriented dimers. We argue that considering this phenomenon is essential for understanding the subgap excitations in artificially designed magnetic nanostructures at the surfaces of superconductors.

Results

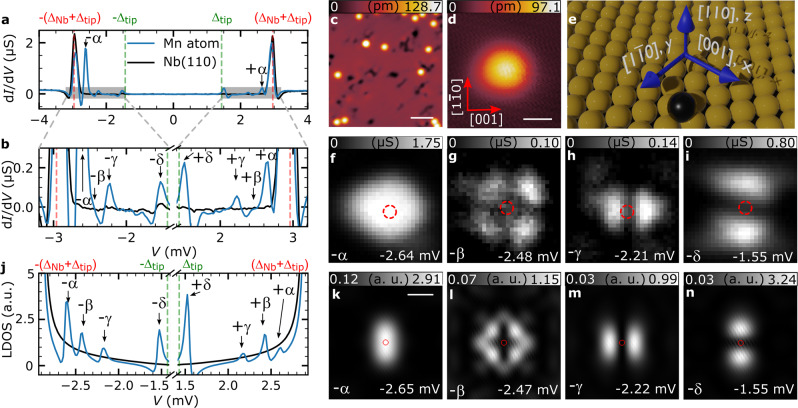

Multi-orbital Shiba states of single Mn adatoms

Mn atoms were deposited on a clean Nb(110) surface (Fig. 1c, see the “Methods” section) and are adsorbed on the hollow site in the center of four Nb atoms (Fig. 1e). First, we revisit the dI/dV spectra of the single adatoms with a considerably better energy resolution than reported previously18 (Fig. 1a, b) which is achieved using superconducting tips and lower temperatures (see the “Methods” section). Compared to the spectra taken on bare Nb(110), they reveal four pairs of additional resonances inside the superconductor’s energy gap, one at positive and one at negative bias symmetrically with respect to the Fermi energy EF (V = 0 V), which we label ±α, ±β, ±γ, and ±δ. The resonance labeled ±β is only visible as a shoulder of the ±α peak. Using dI/dV maps, we determine the spatial distribution19,20,30 of these four resonances, revealing an astonishing resemblance to the shape of the well-known atomic d-orbitals (Fig. 1f–i, see the corresponding maps of the positive bias partner in Supplementary Fig. 5). The energetically highest and most intense state ±α has a circular shape and faint lobes along the [001] (x) and (y) direction (Fig. 1f and Supplementary Fig. 5a), which hints towards an origin in the

Shiba states of single Mn adatoms on Nb(110).

a dI/dV spectra obtained on bare Nb(110) (black) and over a Mn adatom (blue). Red and green vertical lines mark the positions of the coherence peaks ±(ΔNb + Δtip) and the tip gap Δtip, respectively. b Magnification of the spectra shown in panel a. The coherence peaks and the two peaks with the largest intensity are left out for the sake of visibility. Shiba states are labeled and marked by arrows. c Overview STM image of the Mn/Nb(110) sample, where bright protrusions are single Mn adatoms and black depressions correspond to residual oxygen. The white scale bar has a length of 3 nm. (Vbias = 100 mV and I = 200 pA). d STM image of a single Mn adatom, which was used for recording the spectra in a and b, as well as for the dI/dV maps in f–i. The white scale bar has a length of 500 pm and the red arrows point along two high symmetry directions

Hybridization of Shiba states in ferromagnetic dimers

We now turn to the investigation of the Shiba states in Mn dimers. We can tune the magnetic exchange interaction between FM and AFM by laterally manipulating one of the adatoms with the STM tip (see the “Methods” section), thereby varying the crystallographic direction and interatomic spacing. The positions of the two atoms in all manipulated dimers have been determined as described in the “Methods” section, Supplementary Note 2 and Supplementary Fig. 2. We first consider the close-packed dimer along the

![Hybridized Shiba states in a FM-coupled 2a−[11¯0] Mn dimer.](/dataresources/secured/content-1766029688767-99a5b9d9-44cf-4739-9ce9-28289a7cc2f1/assets/41467_2021_22261_Fig2_HTML.jpg)

Hybridized Shiba states in a FM-coupled

a dI/dV spectrum taken between the two atoms of a

Model calculations (see the “Methods” section) using the scattering channel parameters determined for the adatom support these conclusions (Fig. 2k–s and Supplementary Fig. 17). There are eight pairs of Shiba states of the dimer visible as peaks in the calculated LDOS (Fig. 2k), which may be separated into symmetric and antisymmetric combinations with respect to the xz mirror plane, as it was performed for the experimental images. Based on the spatial profiles of the states (Fig. 2l–s) we denote them as ±αs and ±αa (Fig. 2n, o), ±γs and ±γa (Fig. 2p, q), as well as ±δs and ±δa (Fig. 2r, s), respectively. The two additional states (Fig. 2l, m) which are not observed in the experiment are assigned to the ±βs and ±βa states, although their spatial profile also shows similarities with the α states being close by in energy. The latter states were separated from each other by performing calculations with a higher energy resolution than shown in Fig. 2k. Comparing experimental and theoretical results of the energetic shifts of the hybridized Shiba states relative to the single-adatom states and the splitting of symmetric and antisymmetric states (Table 1), we can conclude that the model reproduces the experimental results reasonably well.

| Shiba state | Experiment | Theory | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Shift (μV) | Splitting (μV) | Shift (μV) | Splitting (μV) | |

| α | +120 | +140 | +60 | +180 |

| β | − | − | +195 | −30 |

| γ | +260 | −130 | +30 | +120 |

| δ | +330 | +240 | +200 | +400 |

Hybridization of Shiba states in antiferromagnetic dimers

To investigate the effect of the spin configuration on Shiba states of a dimer and to check for the reported absence of split Shiba states in AFM-coupled dimers31,32, we study the nearest-neighbor dimer constructed along the diagonal of the centered rectangular unit cell (denoted as

![STS of hybridized Shiba states in an AFM-coupled 3a/2−[11¯1] Mn dimer.](/dataresources/secured/content-1766029688767-99a5b9d9-44cf-4739-9ce9-28289a7cc2f1/assets/41467_2021_22261_Fig3_HTML.jpg)

STS of hybridized Shiba states in an AFM-coupled

a dI/dV spectrum taken between the two atoms of a

Role of SOC for the hybridization of Shiba states

In order to find a theoretical explanation for this experimental observation, we first discuss the origin of the degeneracy of the Shiba states in AFM-coupled dimers based on symmetry arguments. In the absence of magnetic impurities, the system may be characterized by a Hamiltonian which is invariant under time reversal, represented for spin-1/2 systems by the antiunitary operator

![Calculation of hybridized Shiba states in an AFM-coupled 3a/2−[11¯1] Mn dimer.](/dataresources/secured/content-1766029688767-99a5b9d9-44cf-4739-9ce9-28289a7cc2f1/assets/41467_2021_22261_Fig4_HTML.jpg)

Calculation of hybridized Shiba states in an AFM-coupled

LDOS inside the superconducting gap calculated between the two atoms of the out-of-plane AFM-aligned dimer (blue), for a single adatom (black) and on the bare superconductor (gray), a without and f with taking SOC into account. The spectrum is convoluted with the superconducting DOS of the tip. Shiba states are labeled and marked by arrows. Two-dimensional maps of the LDOS at the indicated bias voltages show the spatial profiles of the states without (b–e) and with (g–n) SOC. Red circles denote the positions of the adatoms in the dimer. The white scale bar has a length of 500 pm. The crystallographic axes are the same as in Fig. 3b. Magnetic and non-magnetic scattering parameters with and without SOC are given in Supplementary Tables 1 and 2, respectively.

| Shiba state | Experiment | Theory | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Shift (μV) | Splitting (μV) | Shift (μV) | Splitting (μV) | |

| α | +15 | −130 | −195 | +150 |

| β | − | − | +135 | +30 |

| γ | +120 | −400 | −165 | −150 |

| δ | +25 | −110 | +170 | −100 |

Discussion

In conclusion, we demonstrated that the Shiba states of a Mn adatom on the Nb(110) substrate hybridize and split in dimers with considerable overlap between the states. This can be observed not only in FM-coupled but also in AFM-coupled dimers, with a similar magnitude of the energy splitting for both cases. Our theoretical analysis attributes this phenomenon to the breaking of an effective time-reversal symmetry of the AFM dimer, which would otherwise protect the degeneracy of the Shiba states, by SOC in the non-centrosymmetric system. Note that this splitting is not expected to occur for impurities in centrosymmetric bulk systems. There, the atoms in the dimer may be exchanged by spatial inversion P, rather than only by the C2 rotation discussed above. Since the spins remain invariant under spatial inversion, the TP symmetry would then be sufficient to enforce the degeneracy of the Shiba states. An effective time-reversal symmetry Tr is commonly found not only in antiferromagnetic dimers, but in antiferromagnetic chains and two-dimensional structures as well. The breaking of this symmetry by the SOC in non-centrosymmetric systems should clearly distinguish the emergent MBS in Shiba bands from their counterparts in time-reversal invariant systems42,47. Most importantly, our findings indicate that observing the presence or the absence of the splitting of Shiba states in dimers on surfaces cannot be used as a fingerprint for the type of exchange interaction between two magnetic impurities28,31. These results should motivate to revisit previous experimental observations of Shiba states and theoretical predictions on the formation of MBS at the ends of Shiba atom chains by taking into account the SOC in systems with broken inversion symmetry48, shedding new light on these potential building blocks of topological superconductors.

Methods

STM and STS measurements

All experiments were performed in a home-built ultra-high vacuum STM setup, operated at a temperature of 320 mK49. STM images were obtained by stabilizing the STM tip at a given bias voltage Vbias applied to the sample and tunneling current I. dI/dV spectra were obtained using a standard lock-in technique with a modulation frequency of fmod = 4142 Hz, a modulation voltage of Vmod = 20 µV added to Vbias, and stabilization of the tip at Vstab = 6 mV and Istab =1 nA before opening the feedback and sweeping the bias. To visualize spatial distributions of the Shiba states, we defined spatial grids on the structure of interest with a certain pixel resolution, typically with a spacing of about 50–100 pm between grid points. dI/dV spectra were then measured on every point of the grid, with the parameters listed above except for a different modulation voltage of Vmod = 40 µV. dI/dV maps are slices of this dI/dV grid evaluated at a given bias voltage.

We used an electrochemically etched and in-situ flashed tungsten tip, which was indented a few nanometers into the niobium surface, covering it with niobium and producing a superconducting apex of the tip.

We achieved a considerably better energy resolution as compared to previous results obtained on this sample system18 by performing experiments at a lower temperature (320 mK) and making use of superconducting probe tips. Based on a dI/dV spectrum taken on a patch of clean Nb(110) we find the two substrate coherence peaks at ±2.93 mV as indicated by the red vertical lines in Fig. 1a. From measurements with a normal metal tip, we deduce a superconducting gap of ΔNb = 1.50 mV (see Supplementary Note 3). Thereby, the shift in the position of the coherence peaks in the measurement with the superconducting STM probe tip can be used to determine its superconducting gap of Δtip = 1.43 mV 30. All Shiba states in the dI/dV spectra and maps shown here are correspondingly shifted in energy by Δtip.

Sample preparation

The Nb(110) single crystal with a purity of 99.999% was introduced into the ultra-high vacuum chamber and subsequently cleaned by Ar ion sputtering and flashing to about 2400 °C to remove surface-near oxygen50. Mn atoms were evaporated to the sample while keeping the substrate temperature below 10 K, to achieve a statistical distribution of single adatoms (see Fig. 1c, Supplementary Note 1 and Supplementary Fig. 1a). Combining the knowledge of the position of single Mn adatoms with respect to the Nb(110) surface unit cell visible in atomically resolved STM images (Supplementary Fig. 1b) with atom-manipulation images (Supplementary Fig. 1c), with the fact that we find identical features in dI/dV spectra for all single Mn adatoms, as well as with the results of first-principles calculations (Supplementary Note 6), we conclude that the only energetically stable adsorption site for Mn adatoms on Nb(110) is the hollow site in the center of four Nb atoms (Fig. 1e). Artificial dimers were constructed using STM tip-induced atom manipulation from two single adatoms with a typical tunneling resistance of about 60 kΩ. As shown in atom-manipulation images (Supplementary Fig. 1c), the height of the STM tip reveals a characteristic signal while manipulating an atom from one adsorption site to a neighboring one. This signal is used to predetermine the adsorption sites of the two atoms in the dimer during its manipulation process. In combination with the size and orientation of the elliptical shape revealed in an STM image of the resulting dimer, and the possible adsorption sites given by atom-manipulation images overlaid onto the STM image (Supplementary Note 2 and Supplementary Fig. 2), the positions of the two atoms in each dimer indicated in Figs. 2d and 3c are determined unambiguously.

Model calculations

The system was described by the Hamiltonian

In Eqs. (1)–(5),

The LDOS was calculated using a Green’s function-based method28,52,56. The Green’s function at complex energy z is expressed as

The LDOS was calculated as

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41467-021-22261-6.

Acknowledgements

P.B., R.W. and J.W. gratefully acknowledge funding by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG, German Research Foundation)—SFB-925—project 170620586. L.S., R.W. and J.W. gratefully acknowledge funding by the Cluster of Excellence ‘Advanced Imaging of Matter’ (EXC 2056—project ID 390715994) of the DFG. R.W. gratefully acknowledges funding of the European Union via the ERC Advanced Grant ADMIRE (grant No. 786020). L.R. gratefully acknowledges funding from the Alexander von Humboldt Foundation. Financial supports of the National Research, Development, and Innovation (NRDI) Office of Hungary under Project Nos. FK124100 and K131938, and of the NRDI Fund (TKP2020 IES, Grant No. BME-IE-NAT) are gratefully acknowledged by A.L., K.P., L.R. and L.Sz. We acknowledge fruitful discussions with Thore Posske, Stephan Rachel and Dirk Morr.

Author contributions

P.B., L.S. and J.W. conceived the experiments. P.B. and L.S. performed the measurements and analyzed the experimental data together with J.W. P.B. and L.R. prepared the figures. K.P. performed the VASP calculations. A.L. performed the SKKR calculations and discussed the data with K.P., L.R. and L.Sz. L.R. performed the model calculations. P.B., L.R. and J.W. wrote the manuscript. P.B., L.S., L.R., K.P., A.L., L.Sz., J.W. and R.W. contributed to the discussions and the corrections of the manuscript.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Data availability

The authors declare that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the paper and its supplementary information files.

Code availability

The analysis codes that support the findings of the study are available from the corresponding authors on reasonable request.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

References

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

6.

7.

8.

9.

10.

11.

12.

13.

14.

15.

16.

17.

18.

19.

20.

21.

22.

23.

24.

25.

26.

27.

28.

29.

30.

31.

32.

33.

34.

35.

36.

37.

38.

39.

40.

41.

42.

43.

44.

45.

46.

47.

48.

49.

50.

51.

52.

53.

54.

55.

56.

Spin-orbit coupling induced splitting of Yu-Shiba-Rusinov states in antiferromagnetic dimers

Spin-orbit coupling induced splitting of Yu-Shiba-Rusinov states in antiferromagnetic dimers