- Altmetric

Biological activity is often highly concentrated on surfaces, across the scales from molecular motors and ciliary arrays to sessile and motile organisms. These ‘active carpets’ locally inject energy into their surrounding fluid. Whereas Fick’s laws of diffusion are established near equilibrium, it is unclear how to solve non-equilibrium transport driven by such boundary-actuated fluctuations. Here, we derive the enhanced diffusivity of molecules or passive particles as a function of distance from an active carpet. Following Schnitzer’s telegraph model, we then cast these results into generalised Fick’s laws. Two archetypal problems are solved using these laws: First, considering sedimentation towards an active carpet, we find a self-cleaning effect where surface-driven fluctuations can repel particles. Second, considering diffusion from a source to an active sink, say nutrient capture by suspension feeders, we find a large molecular flux compared to thermal diffusion. Hence, our results could elucidate certain non-equilibrium properties of active coating materials and life at interfaces.

Fick’s laws describe the essential physics of diffusion, but it is challenging to extend them to systems out of equilibrium. The authors derive the diffusivity of particles near active carpets - a surface covered with hydrodynamic actuators, which provides a framework for transport in living matter.

Introduction

Imagine a particle floating in outer space, surrounded by uniformly distributed stars that all exert a gravitational force on it. On average, the total force is zero, by symmetry, but its variance is infinite, as described by the Holtsmark distribution1. Microscopically, a similar situation occurs when molecular motors or swimming cells generate long-ranged flows and fluctuations in ‘living fluids’2–12. These active suspensions operate far from thermal equilibrium where surprising effects emerge that fundamentally impact biological processes, including enhanced diffusion of enzymes13–15, viscous and chaotic mixing by motility16–23, viral infections24, bioconvection25–27, oxygen redistribution28, nutrient uptake29–32 and communication via hydrodynamic trigger waves33.

Besides active suspensions, biological activity is commonly concentrated on surfaces. Hence, ‘active carpets’ can form that drive systems out of equilibrium by injecting energy from boundaries. These carpets exist across the length scales: Inside cells, cytoskeletal motors generate cytoplasmic streaming while membranes host catalysing enzymes and transport proteins, all producing non-equilibrium fluctuations and active stresses34–40. Outside cells, ciliary arrays create globally directed flows across entire organs but locally also facilitate mixing41–47, which together may enhance pathogen clearance48. Cells themselves accumulate on surfaces too, driving flows to replenish nutrients, including biofilms or microbial colonies49–53 and sessile suspension feeders54–58. Multicellular organisms also drive feeding currents from walls, including sponges, reef corals59,60, carpets of upside-down Cassiopea jellyfish61 and other macrobenthos62 at larger Reynolds numbers. Beyond biological hotspots, synthetic active carpets have been developed, including artificial cilia63,64, self-propelled droplets and colloids9,10,65,66, engineered bacterial carpets67,68, molecular motility assays69, light-controlled microfluidic flow networks70, hydrogel actuators, liquid crystal elastomers and other responsive materials71–73.

In this article, the properties of non-equilibrium diffusion of molecules or passive particles are examined near such active carpets that generate long-ranged flows. We distinguish between various types of carpets that inject energy into the surrounding medium in different ways: We consider actuators that exert a net force on the liquid (like pumping cilia or sessile suspension feeders), a net torque (like mixing rotors), or a net stress (like swimming bacteria). First, we show how the resulting active fluctuations decay with distance from the surface. Next, we derive the space-dependent diffusivities for the different carpet types, verified by hydrodynamic simulations, and the corresponding generalised Fick’s laws are written out. These laws are then used to solve the active analogue of two classic problems: We first examine sedimentation of particles towards an active carpet. Instead of following the Boltzmann distribution, the particles can be repelled by the fluctuations close to the surface, so the surface features an active self-cleaning effect. We then consider the diffusion of molecules (or particles) from a source to an active sink, such as a surface covered with sessile suspension feeders. The nutrient flux (or particle capture rate) is found to scale quadratically with the active forcing, so it can be significantly larger than the flux due to thermal diffusion. Overall, these problems can be described by relatively simple equations, even if the resulting dynamics feature unexpected solutions.

Results

Active carpet definition

We consider an active carpet made of actuators that generate flows at low Reynolds numbers near a planar no-slip surface (Fig. 1a–d). The surface is located at z = 0. The actuators have position and orientation unit vector

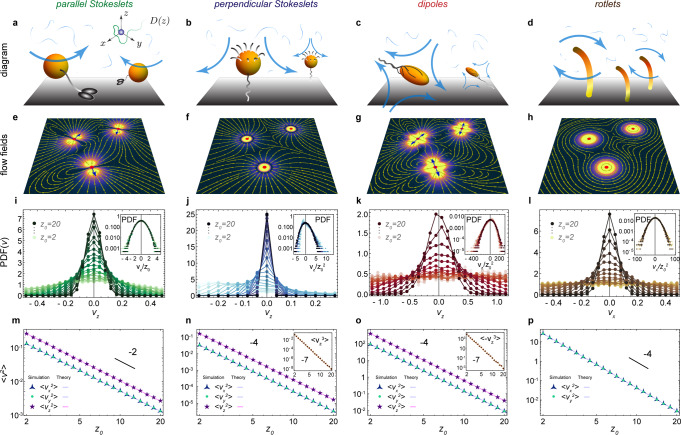

Flows driven by different types of active carpets.

Diagrams of a few examples: a Molecular motors walking along a surface, described by parallel Stokeslets. b Sessile suspension feeders that draw in feeding currents, described by perpendicular Stokeslets. c

E. coli bacteria swimming along a surface, described by Stokes dipoles. d Actuators that rotate about the z-axis, such as nodal cilia, described by Stokes rotlets. e–h Flow fields generated by these different actuator types, shown in the xy plane at z0 = 2h. i–l Probability distribution functions, PDF(vz), of the total flow velocity due to Na = 105 actuators, at different heights z0. Insets show rescaled histograms that highlight skewness and kurtosis, especially for small z0 values. m–p The variance of these distributions,

For example, molecular motors walking or cells crawling along a substrate can entrain the surrounding fluid (Fig. 1a)34–37,39,40. This can be described by a ‘parallel Stokeslet’, a point force f∥ oriented parallel to the surface, giving rise to the flow

To be explicit, we have written out the full expressions of these first multipoles in ‘Methods: Individual flow fields’, and their corresponding flow fields are illustrated in Fig. 1e–h. Also note, throughout this paper we consider non-dimensional quantities in our simulations and figures, but all results can be predicted by analytical expressions, into which dimensional values can be inserted. Hence, we will discuss our results for typical numbers in biology.

Once the individual flows

Active fluctuations

Even if the mean flow generated by the actuators is equal to zero, its variance at any one time is not. Hence, the flows can lead to ‘active fluctuations’ that push and pull on particles near the carpet. We first determine the strength of these fluctuations numerically. A carpet is simulated by placing Na actuators that are randomly distributed with a uniform surface density n within the xy plane. We then evaluate the total flow

We first focus on carpets made of Stokeslets oriented parallel to the surface, with uniformly distributed orientations, so pz = 0 and F = n/2π. Figure 1i shows the resulting histogram of the total vertical flow, vz, for different values of z0. This distribution is an even function, by symmetry of the parallel Stokeslet, so it is immediately clear that the mean flow vanishes. However, the width is finite and decays with distance from the surface, so the active fluctuations are stronger closer to the carpet. This variance can be calculated analytically,

Physically, this expression represents how deeply the active boundary can influence the passive bulk fluid. This theoretical result is listed in Table 1 (row 4, column 3), and it is compared with simulations in Fig. 1m (magenta line). The decay with distance is

| γ | Parallel Stokeslets | Perpendicular Stokeslets | Parallel dipoles | Rotlets | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | 1 | (0, 0, 0) | (0, 0, 0) | (0, 0, 0) | (0, 0, 0) |

| Variance | 2 | ||||

| Skewness | 3 | (0, 0, 0) | (0, 0, 0) | ||

| Kurtosis | 4 |

Moreover, when repeating this algebra for Stokeslets oriented perpendicular to the surface, we find that

The distributions of the active fluctuations,

Space-dependent diffusivity

To understand how these active fluctuations may lead to particle diffusion, it is important to realise how exactly they vary over time. Most systems in nature are dynamic, such as bacteria (or synthetic self-propelled particles) that swim over a surface, with some source of stochasticity. As the bacteria move and reorient, the flows they produce change dynamically. Therefore, a particle advected by these flows will trace out a path that is eventually diffusive. As opposed to Brownian motion, though, this diffusion process is not the sum of random kicks that are instantaneous. Instead, the active fluctuations are correlated in time. They have a memory based on the history of the active carpet configuration.

Therefore, we first focus on a simple case with only one memory time scale, τ. Consider a carpet of sessile suspension feeders like Vorticella convallaria, tethered organisms that produce time-varying nutrient currents (Fig. 2a). These are modelled as Na perpendicular Stokeslets that are again uniformly distributed in space, and fixed because they are non-motile. Each organism generates a flow with its own time-varying strength f⊥ = f(t), which is independent of the other organisms. These Na forces fluctuate according to an Ornstein–Uhlenbeck process,

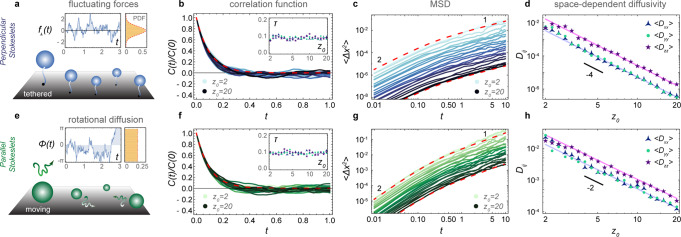

Diffusion driven by an active carpet.

For a–d the surface is covered with sessile perpendicular Stokeslets with independent random forces. Also see Supplementary Movie 1. For e–h the surface is covered by parallel Stokeslets moving along a surface with a constant velocity V and rotational diffusion Dr. For both cases we simulate the motion of tracer particles subject to these active fluctuations, ensemble-averaged over Ne = 100 independent tracer trajectories, as a function of their initial distance from the surface, z0. a Diagram and typical time course of a random force f(t) described by an Ornstein–Uhlenbeck process. b Velocity correlation function (VCF) of the tracer velocity over time. Blue lines show different values of z0, each ensemble-averaged, and the red dashed line is the prediction of Eq. (48). The inset shows that the resulting correlation time τ is independent of z0. c Mean-squared displacement (MSD) for different values of z0, each ensemble-averaged, transitioning from ballistic to diffusive motion. The red dashed lines show the theoretical approximation of Eq. (3) for z0 = 2, 20. d Anisotropic diffusivity in the directions parallel (blue, green) and perpendicular (purple) to the surface. The solid lines show the prediction of Eq. (4). e Diagram and typical time course of the orientation angle ϕa(t) described by rotational diffusion. f–h are equivalent to b–d for moving actuators.

The resulting velocity correlation function (VCF) and mean-squared displacement (MSD) are shown in Fig. 2b and c, respectively. The tracer dynamics are ballistic at short times, t ≪ τ, called the Holtsmark regime. However, at long times they are diffusive with a linear relation 〈Δx2〉 = 2Dxxt, and similarly in the other directions. Hence, we determine the components of the diffusion tensor as a function of z0 (Fig. 2d). Like the flow variances, the vertical component Dzz is five times stronger than the horizontal components, leading to anisotropic diffusion, and they all decay as

This system can be solved analytically when considering the limit of small displacements,

Overall, we find that the diffusion driven by an active carpet can be much stronger than Brownian thermal diffusion. Considering a carpet of Vorticella with cell radius a ~25 μm, h ~150 μm, n ~1/(100 μm)2, τ ~1 s and 8πμf⊥ ~500 pN55, the active diffusion can be dominant up to distances of

Diffusion due to motile actuators

These concepts can be extended to a more complex system with motile actuators (Fig. 2e–h). We consider Stokeslets that move with a constant velocity V along the surface, subject to rotational diffusion Dr, which exert on the liquid a constant force f∥ that is aligned with the direction of motion (see ‘Methods: Simulating the diffusivity of particles near carpets made of moving actuators’). Importantly, this system features multiple time scales: The reorientation time, τr ~ 1/Dr, and the time taken to move underneath a particle, τu ~ z0/V. The corresponding tracer dynamics are therefore more complicated to solve in general, but for slow actuators the decorrelation of the carpet memory is primarily controlled by the rotational diffusion, since τr ≪ τu for small V. Indeed, as shown in Fig. 2f, in that case the VCF simulated for different positions z0 (green lines) closely follows the actuators’ rotational correlation function (red dashed). Then the same theory as before can be applied to predict the MSD (Fig. 2g) and the diffusivity (Fig. 2h). In particular, we can approximate the space-dependent diffusion for parallel Stokeslets as

Again, the active diffusion is significant compared to thermal diffusion. Inserting some typical values into Eq. (5), say h ~ 1 μm, n ~ 1 μm−2, Dr ~ 1 s−1 and 8πμf ~ 1 pN, we have

Generalised Fick’s laws

Once the local diffusivity is determined, we can establish the generalised Fick’s laws (or Fokker-Planck equations) that govern the global stochastic transport. For clarity, we first revise the case of constant diffusion

If the diffusivity is not constant, the spatial dependence may either arise from gradients in the mean speed or an inhomogeneous mean free path78. Indeed, as we saw earlier (Eqs. (4) and (5)), the diffusion tensor

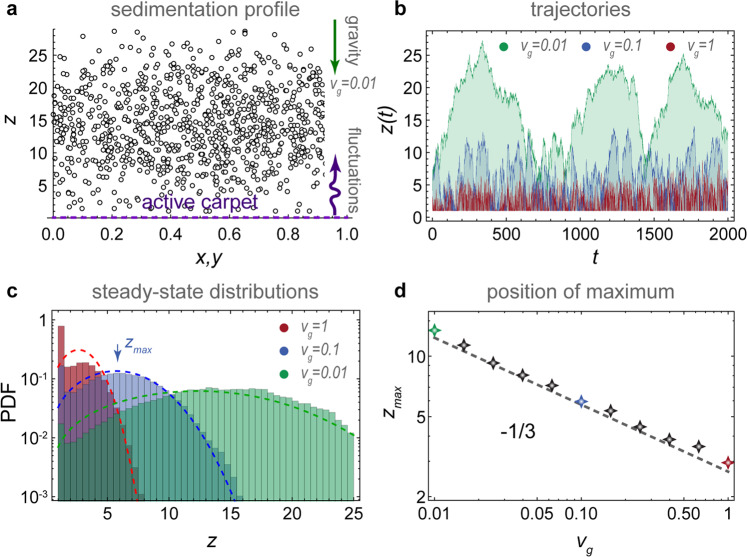

Sedimentation towards an active carpet

As a first application, we consider particles sedimenting towards an active carpet (Fig. 3a, ‘Methods: Sedimentation towards an active carpet: simulation details’). The fluctuations are driven by slowly moving parallel Stokeslets, as before. Typical particle trajectories z(t) are shown for different values of vg, the sedimentation velocity (Fig. 3b). As expected, the particles with the smallest vg reach the highest z positions (green track) but, surprisingly, they hover above the active carpet at some finite height. This phenomenon is somewhat reminiscent of the Leidenfrost effect, where droplets hover above a hot plate. That is, far from the active carpet the particles fall under gravity, but nearby they are repelled by strong active fluctuations (also see Supplementary Movie 2). Because the system is driven out of equilibrium, the sedimentation profile φ(z) does not follow the Boltzmann distribution with an exponential decay. Instead, it features a maximum value (Fig. 3c) with much less particles close to the surface than expected.

Sedimentation towards an active carpet.

Particles sink with velocity vg due to gravity, but are pushed up by the active fluctuations generated by the carpet (dashed purple line), which in this case is composed of moving parallel Stokeslets. a Diagram showing the steady-state sedimentation profile. b Typical trajectories z(t) for a range of sedimentation velocities vg. c Steady-state distributions of particle density for different vg. Histograms show simulations and dashed lines are the prediction of Eq. (8). d Position of the maximum particle density as a function of vg. Markers show simulations and the dashed line is Eq. (9).

To quantify this ‘self-cleaning’ effect, we solve the generalised Fick’s laws for this system analytically. For active fluctuations that scale algebraically with distance from the carpet,

These results agree with our simulations (Fig. 3c, d), for different values of the sedimentation velocity.

The self-cleaning effect can be understood by analysing the generalised flux more carefully (see ‘Methods: Self-cleaning effect’). The first two terms are identical to the case of constant diffusion. However, a third term emerges that represents a flux toward regions where the speed is low. Since the active fluctuations decay with distance, this flux term is always directed away from the active carpet. Importantly, the self-cleaning effect also persists when thermal fluctuations are included in the analysis (see ‘Methods: Sedimentation with active and thermal diffusion’).

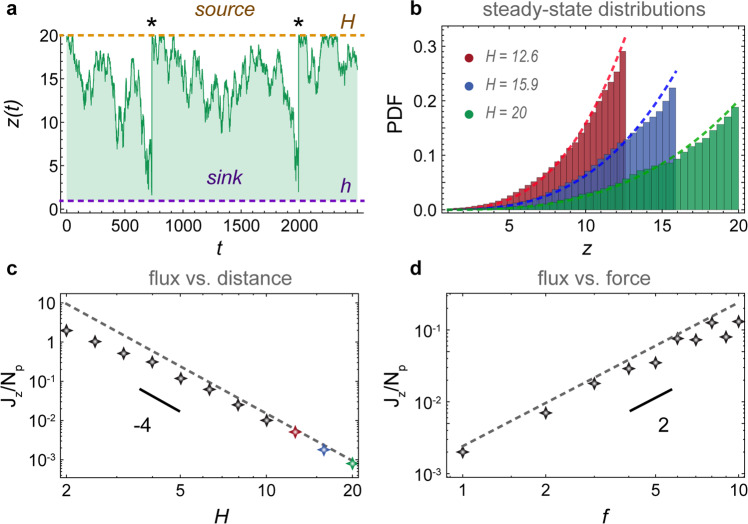

Diffusion from a source to an active carpet sink

Next, we consider particles diffusing from a source to an active carpet sink (Fig. 4a, ‘Methods: Diffusion from a source to an active carpet sink: simulation details’), which could represent particle capture by sessile suspension feeders, or substrate molecules being catalysed by a carpet of enzymes (also see Supplementary Movie 3). Every time a simulated particle diffuses across the absorbing boundary at zsink = h, we place it back at zsource = H. This way, a diffusive flux emerges towards the carpet, which is equivalent to the particle capture rate. Typical trajectories z(t) show that the particles spend the majority of time close to the top surface (Fig. 4a), which is also apparent in the concentration profiles φ(z) that are peaked at the top surface (Fig. 4b). Moreover, the mean first-passage time is much larger for distant sources, so the flux decays rapidly with gap size (Fig. 4c), which may be important for biology or applications in confined spaces.

Diffusion from a source to an active sink.

Particles are spawned at a source (orange line) and subsequently diffuse to a sink (purple line) due to active fluctuations generated by the carpet, which is composed in this case of moving parallel Stokeslets. a Typical trajectory z(t) of a particle. Every time it hits the sink, we place it back at the source (events marked with *). b Steady-state distributions of the particle density for different source positions. Histograms show simulations and dashed lines are Eq. (10). c Diffusive flux as a function of distance. d Diffusive flux as a function of active fluctuation strength. For both c and d the markers show simulations and dashed lines show the prediction of Eq. (82).

This system can again be solved analytically (see ‘Methods: Diffusion from a source to an active carpet sink: theory details’). The flux is given by Eq. (7), with vg = 0 and with fixed particle concentrations at the source and sink. Hence, we must solve the continuity equation ∂zJz = 0 subject to the boundary conditions φ(H) = φ+ and φ(h) = 0. This gives the solution

In the limit of constant diffusion and h ≪ H, we recover the profile φ(z) ≈ φ+z/H, which increases linearly from sink to source, and the flux

Finally, we also examine the effect of different force strengths f∥ on the diffusion to the active sink. Interestingly, we find that the flux scales quadratically with the active fluctuations, so stronger Stokeslets lead to a much larger capture rate (Fig. 4d). Inserting the typical values written below Eq. (5) into Eq. (11), with source concentration φ+ ~ 1 particle/μm and gap size H ~ 10 μm, we find an active flux of ∣Jz∣ ~ 60 s−1. That is more than the thermal flux for micron-sized and molecular particles, ∣Jz∣ ~ 0.05 and 50 s−1, respectively. Interestingly, the thermal and active fluctuations can co-operate to give an even larger flux of ~128 s−1 together (‘Methods: Diffusion from a source to an active carpet sink: comparison with thermal diffusion’). Hence, by enhancing the local diffusivity, the active carpet may increase its nutrient uptake significantly.

Advective and diffusive transport

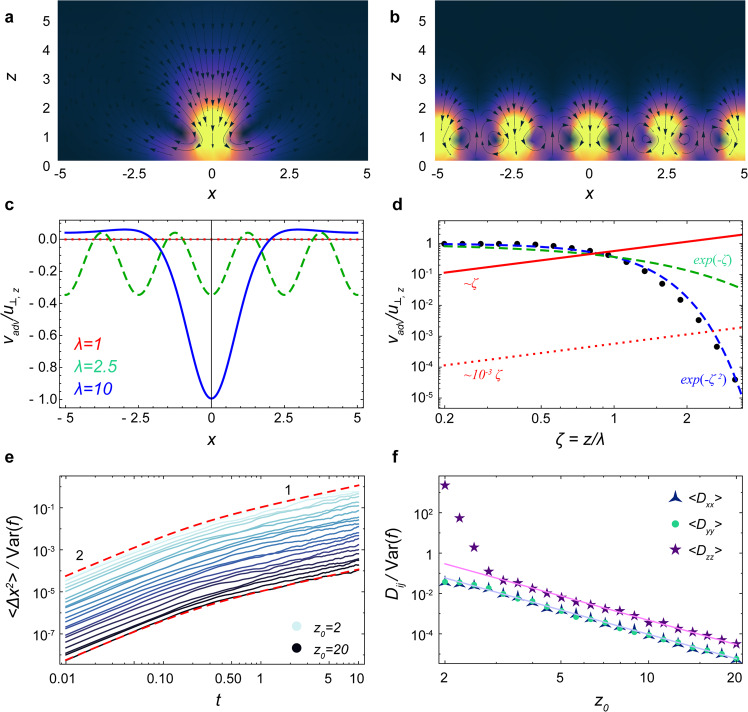

Until now, we have considered active carpets that are spatially uniform, where

To investigate this, we consider a carpet composed of a square lattice of perpendicular Stokeslets that all fluctuate about a non-zero mean force

Comparison of advective and diffusive transport.

Here the active carpet is a square lattice of perpendicular Stokeslets. a, b Flows (Eq. (88)) produced by a carpet of λ = 10 (sparse) and λ = 2.5 (dense), respectively, in the plane y = 0. Colours shows the flow magnitude and black arrows are streamlines. c The total advection flow, vadv,z (x, 0, 2.5), normalised by the flow of a single actuator, u⊥,z (0, 0, 2.5), for different lattice spacings: λ = 10 (blue), λ = 2.5 (green), λ = 1 (red). The flows vanish as λ decreases. d Comparison of advective and active diffusive transport. Black points show the normalised advection flow, Φ(ζ) (see Eq. (89)). The dashed lines are the decaying functions e−ζ (dashed green) and

Discussion

In summary, active carpets are ubiquitous in nature, from molecular and cellular to organismic length scales. In this paper we described how these active carpets can drive non-equilibrium fluctuations by locally injecting energy into their surrounding fluid. These fluctuations were quantified with a general theoretical framework in terms of the fundamental solutions of the Stokes equation. Hence, we derived the diffusivity as a function of distance from an active carpet, and we found the corresponding generalised Fick’s laws. The predictive power of these laws was demonstrated by solving them for two archetypal problems: sedimentation and diffusion towards an active sink. Of course, one could extend this straightforwardly to other problems like diffusion away from an active source, potentially in combination with sedimentation, or systems with multiple active boundary conditions in one or more dimensions.

This framework can be applied to a much more general class of problems. Until now we have considered non-interacting actuators, where the fluctuating forces and associated time scales are determined by their intrinsic properties. It would be interesting to consider actuators featuring different types of collective behaviours2–11, say swarming and clustering, so these forcing properties might emerge collectively. This could lead to interesting types of anomalous diffusion79.

Additionally, one could consider active transport and diffusion in complex geometries (see ‘Methods: Extension to more complex geometries’). Immediate extensions could be carpets on the outside of a sphere, such as cilia covering Volvox carteri30 and microbes covering marine snow80,81, but also carpets on the inside of a spherical cavity, such as motors on the cytoskeleton11. Once these topologies are understood, one could consider more complex curved spaces, like the highly folded active membranes of the endoplasmic reticulum. Furthermore, besides translational diffusion one could derive the rotational diffusion82,83, for spherical but also for ellipsoidal particles and other shapes84. Finally, flows with finite inertia could be modelled to describe carpets with actuators that are large or perform rapid motions33,85.

Besides hydrodynamic actuators, this framework could equally be applied to different kinds of energy injection from surfaces. For example, one could consider active carpets that generate fluctuating electric or magnetic fields, or catalyse chemical reactions. Conversely, there are also surface-driven thermo-osmotic and acoustic fluctuations, or liquid interfaces with a variable surface tension, which can all induce transport and diffusion.

The understanding of active carpets may therefore prove useful in a wide range of applications. Recent advances in nanotechnology enable the design of artificial cilia63,64, origami micromachines86,87, and four-dimensionally printed active materials88. One may therefore think of ‘active coating materials’, for example with self-cleaning properties based on the described effect of boundary-actuated fluctuations repelling particles. One could also consider biomolecular condensates89,90, including phase-separated biopolymers, where chemical reactions are concentrated in one phase but the products are transported to the other phase by mixing actuators at the interface. This idea of interfacial mixing may also be applied to bacteria moving on water–oil interfaces91,92 for bioremediation of oil spills93,94.

Methods

Individual flow fields

The flow generated by an individual actuator is written in terms of the Blake tensor74, given by

The flow due to a point force f∥ oriented parallel to the surface is given by

Note, we have scaled the forces as f = fN/(8πμ), where μ ~ 10−3 Pa s is the viscosity of water, so fN are in Newtons and f have units [m2/s]. The Stokes dipole flow with prefactor κ in [m3/s] is found by taking the derivative along the

Finally, the Stokes rotlet describes an actuator that generates a torque about the z-axis. Its flow with prefactor ϱ in [m3/s] is defined by

These flows fields are quite complex when evaluated algebraically. Therefore, to make progress we approximate the flows as being evaluated far from the surface, such that za = ϵz with ϵ ≪ 1. For each of the individual actuator flows ((14)–(17)) we then perform a Taylor expansion,

To be explicit, for the parallel Stokeslets evaluated at

Similarly, for the perpendicular Stokeslets with the same position and orientation

For Stokes dipoles oriented parallel to the surface, with orientation

Characterising fluctuations: simulation details

To characterise the strength of the active fluctuations, we simulate the distribution

Characterising fluctuations: theory details

We consider active carpets made of uniformly distributed actuators, so the average flow vanishes in the absence of gradients,

The variance tensor of the active fluctuations is calculated in the same way, by evaluating the integral

To give an explicit example, the vertical component of the variance for parallel Stokeslets is given by

This result corresponds to Eq. (2) in the main text, and is compared with simulations in Fig. 1m. We repeat this calculation for the different actuator types, and for the different components, i, j. Note that the off-diagonal components vanish, so the only non-trivial results are i = j. These results are all listed in Table 1.

Besides variance, the distributions of the active fluctuations also feature skewness

For all these quantities, we find that the only non-zero results are diagonal, where i = j = k = l. These results are listed in the bottom rows of Table 1 for all actuator types, and plotted in the insets of Fig. 1i–l.

Simulating the diffusivity of particles near carpets made of fluctuating forces

We first consider the motion of a tracer particle above a carpet of fluctuating forces, composed of Na perpendicular Stokeslets (Eq. (22)) that have a fixed position on the wall. The point forces have vertical position h = 1 and horizontally they are randomly distributed over the surface, with uniform density n = 0.1 per unit area, and within a simulation box of dimensions x, y ∈ [−L, L] with L = 500 so Na = 4nL = 105. We have verified that the simulation box is large enough to avoid edge effects by testing that the results are independent of large L. The tracer is initially located at (0, 0, z0). The forces do not interact with each other. Each perpendicular Stokeslet force f⊥ = fa(t) evolves dynamically in time following its own independent Ornstein–Uhlenbeck process.

This Ornstein–Uhlenbeck process is defined as

This corresponds to an overdamped relaxation process driven by fluctuations, which admits a Gaussian stationary distribution

In our simulations, we use an average force magnitude of 〈f 2〉 = (3/4)2 and τ = 1/10 so that σ2 = 2〈f 2〉/τ, and the initial force f(t = 0) for each actuator is drawn randomly from the stationary distribution (Eq. (41)). Besides these active fluctuations, we do not include additional Brownian thermal fluctuations here.

The tracer’s equation of motion is then given by

By averaging over the ensemble of Ne trajectories we compute the VCFs,

Derivation of the MSD and space-dependent diffusivity

Analytical progress is made by considering small tracer displacements,

Then their equation of motion reduces to

The relationship between this ensemble-averaged flow correlation and the Ornstein–Uhlenbeck force correlations is given by

These expressions are shown in Fig. 2d. The same analysis can also be applied to all other actuator types using the variances listed in Table 1.

Importantly, we should come back to the initial assumption of small displacements (Eq. (44)) and analyse its consequences. Rewriting this condition as z2 ≫ 2Dzzt = 30πnh4〈f 2〉τt/z4 using Eq. (53), we can rearrange this for a temporal condition, t/τ ≪ z6/(30πnh4〈f 2〉τ2). We also require that t ≫ τ for the particle motion to transition from ballistic to diffusive motion (see Eq. (51)). In other words, the theory is only expected to hold when the time scale of diffusive transport is slow compared to the time scale of the active fluctuations themselves. This is true far from the surface, where

Simulating the diffusivity of particles near carpets made of moving actuators

Here, we consider the motion of a tracer particle above a carpet of Na parallel Stokeslets (Eq. (19)) that each move with velocity

These Na + 1 equations of motion, for the tracer and the actuators, are then integrated as before over a time period t ∈ [0, 10] for each tracer trajectory. We repeat this simulation for an ensemble of Ne = 100 independent trajectories, each with an independent carpet realisation with actuators that are initially distributed at different random positions and orientations. Again, we repeat all this for ten different initial positions z0 ∈ [2, 20]. The ensemble-averaged results are shown in Fig. 2e–h.

Generalised Fick’s laws

For clarity, we first revise the case of constant diffusion

Together with the continuity equation, ∂tφ = −∂zJz, this gives Fick’s second law,

Rather than being constant in space, the diffusivity of tracers near an active carpet depends continuously on position. Such stochastic processes can often be described by an effective Smoluchowski equation78, rather than standard Langevin methods which make no reference to individual collisions. Here, we follow this approach as a foundation for the generalised Fick’s laws that describe the diffusion of a tracer particle as a function of distance from an active carpet. Since we only have gradients in the vertical direction, we use the short-hand notations D(z) = Dzz for the vertical diffusivity and

With this spatial dependence, the question arises whether the second term in Eq. (55) should be interpreted as D∂zφ or ∂z(Dφ), or something in between. This question is not well posed, because it depends on the physical processes in question. In other words, generalising this expression for macroscopic quantities requires partial knowledge of the microscopic mechanism for diffusion. In particular, information is needed about the spatial dependence of the memory time τ(z), and of the mean vertical speed, v(z). The diffusivity can then be written as the combination of these ingredients, D(z) = v2(z)τ(z), as shown in Eq. (53). Indeed, either a larger average speed or a longer time between reorientations can give rise to a larger diffusivity. Note that for Ornstein–Uhlenbeck forcing the time scale τ does not depend on position, but this need not be true in general. For example, for rapidly moving actuators the smallest decorrelation time is τ ~ z/V. On the other hand, for slowly moving actuators the rotational diffusion constant Dr sets the smallest memory time.

Using this information about the microscopic interactions, a ‘telegraph model’78 can be constructed that describes the space-dependent diffusion process. Inspired by this model, we consider two particle populations, with population densities φup(z, t) and φdown(z, t), respectively, that either move up or down along z with mean speed v(z) due to the active carpet fluctuations. The mean speed is the same for the two populations at any given z since we consider a uniform carpet without net drift,

In each equation, the first term describes spatial gradients in the moving populations, while the last two terms describe the switching between particles moving up and down, and vice versa. By adding and subtracting, the equations (57) can be rewritten in terms of the total density and diffusive flux, giving

Taking the time derivative of the first expression and combining with the second expression yields

Then, we assume that the high-frequency behaviour of particle movements can be neglected, so the second time derivative on the left-hand side vanishes,

Integrating this expression, we can solve for the diffusive flux Jdiff. The constant of integration is set equal to zero to ensure that Jdiff vanishes when the variance of the active fluctuations v2 are zero. If the particles are sedimenting with a constant drift velocity vd, there is an additional flux Jdrift = vdφ, so the total flux is Jz = Jdiff + Jdrift. Then, combining all this information gives the first generalised Fick’s law in the vertical direction,

We find the other components of the flux by repeating the telegraph model analysis in the x and y directions, which gives

Since the variance tensor only has diagonal components, we can write the generalised flux in three dimensions as

Sedimentation towards an active carpet: simulation details

Here, we consider the motion of a sedimenting tracer particle above a carpet of moving parallel Stokeslets. For spherical particles, the sedimentation is described by a constant drift velocity

Self-cleaning effect

These simulation results can be understood using the generalised Fick’s laws we discussed earlier. The first two terms on the RHS in Eq. (63) are identical to the case of constant diffusion (Eq. (55)), describing a flux of particles towards regions of low concentration. A third emerges, however, which describes diffusion towards regions of low fluid speed. Since the active fluctuations decay with distance (e.g. see Eq. (2)), this term leads to a flux directed away from the carpet.

To understand this better, we must quantify the contributions of the flux. Since the variance of all the active fluctuations in Table 1 feature an algebraic decay, we write

Similarly, for the memory time we write

Then the vertical diffusivity is

The first term is negative for sedimentation, and the second term still describes ordinary diffusion towards regions of low concentration. But the third term is always positive, repelling particles away from the carpet, which explains the self-cleaning effect.

To solve the sedimentation profile, we require that Jz = 0 at steady state, which yields

These results agree with our simulations (Fig. 3c, d), for different values of the sedimentation velocity.

Sedimentation with active and thermal diffusion

Besides the fluctuating flows generated by the active carpet, the particles may also experience Brownian thermal fluctuations. This thermal diffusion Dth can be included explicitly in the generalised Fick’s law:

Then, the expression Jz = 0 can still be solved analytically to determine the steady-state sedimentation profile. For parallel Stokeslets, for example, with α = 2 and β = 0, we find the solution

It is important to note that this function has the same shape as the original solution (Eq. (73)). Indeed, particles are still repelled from the active surface,

Diffusion from a source to an active carpet sink: simulation details

In this section, we consider the dynamics of particles that are spawned at a source and absorbed by an active sink. The particles are subject to active fluctuations due to a carpet of slowly moving parallel Stokeslets. The equations of motion of the Na actuators are as described in ‘Methods: Simulating the diffusivity of particles near carpets made of moving actuators and Sedimentation towards an active carpet: simulation details’. For the tracer equation of motion we remove the sedimentation, we impose an absorbing boundary condition at zsink = h, and a reflecting boundary condition at zsource = H. Whenever a particle is absorbed by the sink, we place it back at the source, at x = y = 0, and we redistribute all the actuators with new random positions and orientations to start a new fully independent trajectory. We run two separate types of simulations: First, the gap size is varied with different values of H ∈ [2, 20] with constant force f∥ = 10. Second, we vary f∥ = ∈ [1, 10] with constant source height H = 5. For each of these forces we measure the flux Jz, defined as the number of particles that diffuse from the source to the sink per unit time, Jz = −Np/〈tmfp〉, where 〈tmfp〉 is the mean first-passage time and Np is the number of particles. By symmetry, we expect the nutrient flux to scale quadratically with the force, because the diffusion equations are invariant under the transformation f → −f. Indeed, this is also observed in the simulations, as shown in Fig. 4.

Diffusion from a source to an active carpet sink: theory details

To solve the system of non-equilibrium diffusion from a source to an active sink, we again consider the vertical flux given by Eq. (7). This time, the sedimentation velocity is equal to zero and we seek the steady-state solution (∂tφ = 0) with fixed particle concentrations at the source and the sink. Hence, we must solve the continuity equation ∂zJz = 0 subject to the boundary conditions φ(H) = φ+ and φ(h) = 0. This gives the solution

When comparing this prediction with the simulated flux, care should be taken to account for the normalisation (Eq. (69)), because the number of particles Np is coupled to concentration φ+ at the top boundary condition φ(H) = φ+. This relationship can also be computed exactly,

Hence, using Eq. (78) for h ≪ H yields

For slowly moving parallel Stokeslets (α = 2 and β = 0), we then have Jz ∝ z−3 for a constant φ+ concentration, or Jz ∝ z−4 for a constant number of particles Np. In Fig. 4c we show the latter.

Diffusion from a source to an active carpet sink: comparison with thermal diffusion

We expect that the thermal diffusion will be more effective at transporting the particles if the distance between the source and the sink is large, because the thermal noise does not decay with z. To quantify this, we equate the active carpet flux (Eq. (81)) with the thermal flux,

The boundary concentration φ+ cancels out, so we find that the value of H for which the two are equal is

Inserting

The diffusive flux can also be computed in the presence of both thermal and active fluctuations. As before, we solve ∂zJz = 0 using the generalised Fick’s law that includes thermal diffusion (Eq. (75)) without gravity, with boundary conditions φ(0) = 0 and φ(H) = φ+. For parallel Stokeslets this yields the concentration profile

As expected, in the limit

Advective and diffusive transport

To investigate the relative importance of local advective and diffusive transport, we consider a carpet composed of perpendicular Stokeslets that fluctuate about a non-zero mean. Then, the Ornstein–Uhlenbeck process (Eq. (39)) becomes

Naturally, the advection is not significant in the limit of a small mean force, when

Hence, the diffusion dominates over advection beyond a distance

Another point to note is that the advective flows can average out in time: Consider a particle located in a down-welling region, slowly moving down towards an actuator. If the particle is also subject to active and/or passive fluctuations, it can diffuse horizontally into an up-welling region, so it can escape. To demonstrate this, we repeat our diffusion simulations (cf. Fig. 2a–d) for a carpet of perpendicular Stokeslets with very weak active fluctuations, Var(f) = 10−6, compared to a strong mean force directed towards the carpet,

The nutrient flux that individual organisms receive therefore depends strongly on the distance of the nutrient source. If the source is located at H < z*, then the flux to individual organisms can be large due to advection. If the source is located at H > z*, then the flux is determined by diffusion. This spreads out the nutrients horizontally before they reach the surface, so on average all organisms receive the same global diffusive flux as discussed in ‘Methods: Diffusion from a source to an active carpet sink: simulation details’.

The theory can also be extended for situations where the relation

Quenched disorder

The connection between advective and diffusive transport is also related to quenched disorder, the notion that spatial heterogeneity can be frozen in place so a spatial average would not be equal to a local temporal average. In other words, a system features quenched disorder if it has random variables that are quenched (frozen) in time, so their dynamics cannot evolve as fast as the other time scales in the system. In general, active carpets can indeed feature quenched disorder. In that case, it would not be appropriate to model the tracer dynamics with the generalised Fick’s laws described here: This modelling approach is based on averaging with respect to a large ensemble of active carpet configurations, so it would not always be informative about the dynamics of a single specific system configuration.

However, the disorder need not necessarily be quenched for active carpets. The relevant random variables are the relative positions and orientations between the actuators and the tracer particles. Therefore, there is no quenched disorder when the actuators meander along the surface, like bacteria, as long as they move or turn rapidly. Similarly, even if the actuators themselves are fixed, the tracers may still diffuse in space under the right conditions, so the relative positions could still vary freely. They key question is what these conditions are.

The first requirement is that the advective transport (due to individual actuators locally) is much weaker than the diffusive transport (due all actuators together, possibly aided by thermal noise). If a tracer is caught in a local actuator current, then its dynamics are effectively quenched; however, if the particle can diffuse away and escape, the ballistic motion disappears and the advection flows tend to average out over time (Fig. 5e, f). Hence, as the particles explore space horizontally, their spreading over time becomes equivalent to spatial averaging, so the dynamics become annealed. As described in previous section, the diffusion dominates advection if the particles are located far away from the active surface (see Eq. (91)).

The second requirement is that the time scale of diffusive transport is slow compared to the time scale of the active fluctuations themselves. This ensures that the tracer motion is diffusive over time and not ballistic according to a specific carpet configuration. As described in ‘Methods: Derivation of the mean-squared displacement and space-dependent diffusivity’, this requirement is satisfied when Eq. (54) holds. Therefore, both requirements are fulfilled beyond a certain distance from the surface.

To verify the generalised Fick’s laws, we compared their predictions with detailed hydrodynamic simulations. These fully resolve all the actuator positions and orientations throughout time, so any quenched disorder is explicitly included. Importantly, all our main findings (enhanced diffusivities, sedimentation profiles, nutrient fluxes) are supported by this data. Indeed, we found that the simulations and the theory agree well with one another beyond a certain distance from the surface, when both requirements described above are fulfilled. Future theories could perhaps relax these conditions by taking the effects of quenched disorder into account. We expect this could be an exciting opportunity of further research in the field of non-equilibrium statistical mechanics and active matter systems.

Extension to more complex geometries

In principle, our theory may be generalised for active carpets of more complex geometries by taking the following steps: First, one should find the hydrodynamic Green’s function (cf. the Blake tensor in Eq. (12)) that satisfies the Stokes equations and the boundary conditions of the geometry in question. Once this flow solution is known, one can start developing simulations to verify the following steps. Second, the mean flow

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41467-021-22029-y.

Acknowledgements

F.G.-L. acknowledges Millennium Nucleus Physics of Active Matter of ANID (Chile). H.L. acknowledges support from the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft, DFG projects SPP 1726 and LO 418/23. A.J.T.M. acknowledges funding from the Human Frontier Science Program (Fellowship LT001670/2017) and the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA-NIFA AFRI grants 2020-67017-30776 and 2020-67015-32330). F.G.-L. and A.M. also acknowledge support from the American Physical Society (APS) for an International Research Travel Award (IRTAP).

Author contributions

F.G.-L. and A.J.T.M. contributed equally to this work and are joint first, last and corresponding authors. F.G.-L., H.L., and A.J.T.M. designed the research and wrote the manuscript. F.G.-L. and A.J.T.M. performed the simulations. A.J.T.M. developed the theory.

Data availability

All simulation data used for this paper are available from the corresponding authors upon request.

Code availability

All simulation codes used for this paper are available from the corresponding authors upon request.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

References

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

6.

7.

8.

9.

10.

11.

12.

13.

14.

15.

16.

17.

18.

19.

20.

21.

22.

23.

24.

25.

26.

27.

28.

29.

30.

31.

32.

33.

34.

35.

36.

37.

38.

39.

40.

41.

42.

43.

44.

45.

46.

47.

48.

49.

50.

51.

52.

53.

54.

55.

56.

57.

58.

59.

60.

61.

62.

63.

64.

65.

66.

67.

68.

69.

70.

71.

72.

73.

74.

75.

76.

77.

78.

79.

80.

81.

82.

83.

84.

85.

86.

87.

88.

89.

90.

91.

92.

93.

94.

Active carpets drive non-equilibrium diffusion and enhanced molecular fluxes

Active carpets drive non-equilibrium diffusion and enhanced molecular fluxes