Understanding how natural selection has shaped genetic architecture of complex traits is of importance in medical and evolutionary genetics. Bayesian methods have been developed using individual-level GWAS data to estimate multiple genetic architecture parameters including selection signature. Here, we present a method (SBayesS) that only requires GWAS summary statistics. We analyse data for 155 complex traits (n = 27k–547k) and project the estimates onto those obtained from evolutionary simulations. We estimate that, on average across traits, about 1% of human genome sequence are mutational targets with a mean selection coefficient of ~0.001. Common diseases, on average, show a smaller number of mutational targets and have been under stronger selection, compared to other traits. SBayesS analyses incorporating functional annotations reveal that selection signatures vary across genomic regions, among which coding regions have the strongest selection signature and are enriched for both the number of associated variants and the magnitude of effect sizes.

Methods to study how natural selection shapes genetic architecture of complex traits rely on individual level genome-wide association study (GWAS) data. Here, the authors present a Bayesian method using GWAS summary statistics to study genetic architecture and apply this to 155 complex traits.

The joint distribution of SNP effect size and minor allele frequency (MAF) is an essential component of the genetic architecture of human complex traits and is influenced by natural selection1. A negative relationship between effect size and MAF is a signature of negative (or purifying) selection2,3, which prevents mutations with large deleterious effects becoming frequent in the population. Understanding how natural selection has shaped genetic variation helps researchers to improve experimental designs of genetic association studies4 and the estimation of SNP-based heritability (the proportion of phenotypic variance explained by the SNPs)5–9. Inference on natural selection is also a critical step towards the understanding of the genetic architecture of complex traits. For instance, the theory of negative selection10 explains why the effects of common variants identified by genome-wide association studies (GWAS) are unlikely to be large11,12.

We have recently developed a Bayesian method (BayesS) to estimate the effect size–MAF relationship, which was considered as a free parameter (S) in the model13. We detected negative for a number of complex traits in humans, highlighting an important role of negative selection in shaping the genetic architecture, consistent with the findings from other studies based on genome-wide variance estimation approaches7,11,14,15. The BayesS model also allows us to estimate the SNP-based heritability and polygenicity (the proportion of SNPs with nonzero effects) to better describe the genetic architecture for a trait. The application of BayesS has been restricted to GWAS samples with individual-level genotypes but for most common complex diseases, only summary-level data are publicly available. Moreover, despite the implementation of a parallel computing strategy13, it remains computationally challenging to run BayesS for biobank-scale data, as the computing resource required increases linearly with the number of individuals or SNPs.

In this study, we enhance the BayesS model such that the analysis only requires GWAS summary statistics and a sparse linkage disequilibrium (LD) correlation matrix from a reference sample. This method (referred to as Summary-data-based BayesS or SBayesS) opens an opportunity to disentangle the genetic architecture of complex traits (including diseases) using publicly available data sets of the largest sample sizes to date, with merely a small fraction of the computational resource required for BayesS. We perform extensive analyses to benchmark between SBayesS and BayesS, and apply the SBayesS methods to GWAS summary statistics from the full release of the UK Biobank16 (UKB) data and other published studies17–25, followed by time-forward simulations26 for evolutionary inference and SBayesS analyses that incorporated functional genomic annotation data. We detect widespread signatures of negative selection in the genetic architecture across 155 complex traits with a predicted mean selection coefficient of ~0.001 and a predicted mean proportion of human genome sequence being mutational targets of ~1%, among which common diseases show a relatively higher mean selection coefficient and a relatively smaller number of mutational targets. Meta-analysis across traits reveals differential signatures of negative selection across functional genomic regions, among which coding regions have the strongest selection signature and are enriched for both trait-associated variants and those with large effect sizes.

BayesS is a method that can estimate three key parameters to describe the genetic architecture of complex traits by a Bayesian mixed linear model13, namely SNP-based heritability (

In light of recent studies11,28, which point out a possible lack of fit of a point–normal mixture model to some traits, we further extended SBayesS to a multi-component mixture model (referred to as SBayesRS), following the framework of SBayesR29. In SBayesRS, each SNP effect is assumed to have a mixture of a point mass at zero and three normal distributions with mean zero and variances that differ by a factor of 10 (see the “Methods” section). This flexible prior accounts for a more complex genetic architecture with a spectrum of very small to very large effect sizes. The S parameter and overall polygenicity are estimated based on the SNPs across all nonnull mixture components.

To better understand the variability of regional genetic architecture in different parts of the genome, we incorporate functional genomic annotations into SBayesS to allow the three key parameters to vary in different annotation categories, e.g., coding, regulatory and repressed regions. We performed the functional partitioning SBayesS analysis (denoted SBayesS-strat) based on a two-component model that fitted SNPs in one annotation as the first component and the rest of the SNPs as the second component (see the “Methods” section). During MCMC sampling, the enrichment of a parameter in an annotation category is computed as the ratio of the sampled value of the parameter in the category to that for the whole genome (see the “Methods” section).

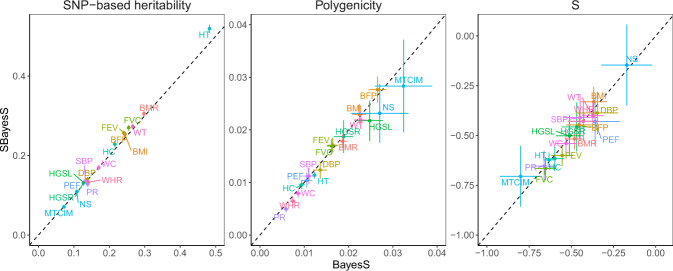

We ran both SBayesS and BayesS with ~1.1 million HapMap3 SNPs with MAF ≥ 0.01 for 18 quantitative traits (n > 100k) as analysed in Zeng et al. 13. We used the HapMap3 SNPs as they were optimised to tag common genetic variants30 and are widely used in the literature which improves the comparability of our results with those generated using published GWAS summary statistics. Hence, the reported parameters are specific to this SNP set. For ease of computation, we used unrelated individuals of European ancestry from the interim release of the UKB data for the BayesS analysis (maximum n = 120k across traits) and the same data to generate GWAS summary statistics for the SBayesS analysis. We show in Fig. 1 that the correlation between the SBayesS and BayesS estimates for all of the three genetic architecture parameters was close to one across traits (Pearson correlation r = 0.998 for

Benchmarking SBayesS with BayesS using the same data for 18 UKB traits.

Three genetic architecture parameters were compared, i.e., SNP-based heritability, polygenicity (defined as proportion of SNPs with nonzero effects) and S (defined as relationship between MAF and effect size), based on the unrelated individuals of European ancestry in the interim release of the UKB data (max n = 120k) and ~1.1 million HapMap3 common SNPs (MAF > 0.01). The sparse LD matrix used in SBayesS was computed from a random sample of 50k unrelated individuals from the full UKB cohort at a chi-squared threshold of 10 (corresponding to a LD r2 threshold of 2 × 10−4). Data are presented as posterior means ± posterior standard errors. The traits are indicated by different colours labelled with their acronyms. BMR basal metabolic rate, BMI body mass index, BFP body fat percentage, DBP diastolic blood pressure, FEV forced expiratory volume, FVC forced vital capacity, HGSL hand grip strength (left), HGSR hand grip strength (right), HCadjBMI hip circumference adjusted for BMI, HT height, MTCIM mean time to correctly identify matches, NS neuroticism score, PEF peak expiratory flow, PR pulse rate, SBP systolic blood pressure, WCadjBMI waist circumference adjusted for BMI, WHRadjBMI waist–hip ratio adjusted for BMI, WT weight.

We performed additional sensitivity analyses to investigate the impact of the sparsity of LD matrix, the SNP panel, the choice of reference sample and the reference sample size on the performance of SBayesS. We found that SBayesS was robust to different chi-squared thresholds used for LD filtering (Supplementary Fig. 2) and gave consistent results with BayesS regardless of whether using HapMap3 (Fig. 1) or UKB Axiom array panel (Supplementary Fig. 3a). The analysis using HapMap3 SNPs tended to give slightly lower

The parameter estimates were largely consistent between SBayesS and SBayesRS except for polygenicity, of which the estimate from SBayesRS was higher than that from SBayesS (Supplementary Fig. 9a). This is because, on one hand, SBayesS has a relatively low power to detect SNPs with very small effect sizes due to its assumption of a single normal distribution; on the other hand, SBayesRS tends to overestimate the number of SNPs with very small effect sizes due to the insufficient power to distinguish very small effect sizes from zero, as suggested by simulation (Supplementary Fig. 9c). Nevertheless, the number of SNPs with relatively large effects estimated from SBayesS was mostly consistent with that from SBayesRS (Supplementary Fig. 9b).

Finally, we tested the method in application to ascertained case-control data by simulation. The parameter estimates were nearly unbiased regardless of whether cases were oversampled, although the sampling variances of the estimates of polygenicity and S were relatively large in some simulation scenarios where the number of cases was relatively small (Supplementary Fig. 10).

We applied SBayesS to analyse the full release of the UKB data, including 26 complex traits and 9 common diseases (Supplementary Table 1). Although individual-level data are available in the UKB, application of the standard BayesS to ~350k unrelated individuals with ~1.1 million HapMap3 SNPs is computationally prohibitive. Prior to running SBayesS, we carried out standard quality control (QC) of the data (see the “Methods” section) and used linear regression to perform a GWAS analysis in unrelated individuals to generate summary statistics for each trait. We also applied SBayesS to data for 9 other complex common diseases from published GWAS of very large sample size where only summary statistics are available (Supplementary Table 2). In the analysis of the UKB data, we used the sparse LD matrix computed from a random sample of 50k unrelated individuals. For the analysis of data from published GWAS of which nearly all the samples are of European ancestry, the GERA32 sample was used as the LD reference. To mitigate the problem due to inconsistent LD between the GWAS and reference samples, we excluded SNPs in the major histocompatibility complex (MHC) region although the SBayesS results with and without the MHC region were very similar (Supplementary Fig. 11). The SNP-based heritability estimates for the diseases were converted to those on the liability scale33.

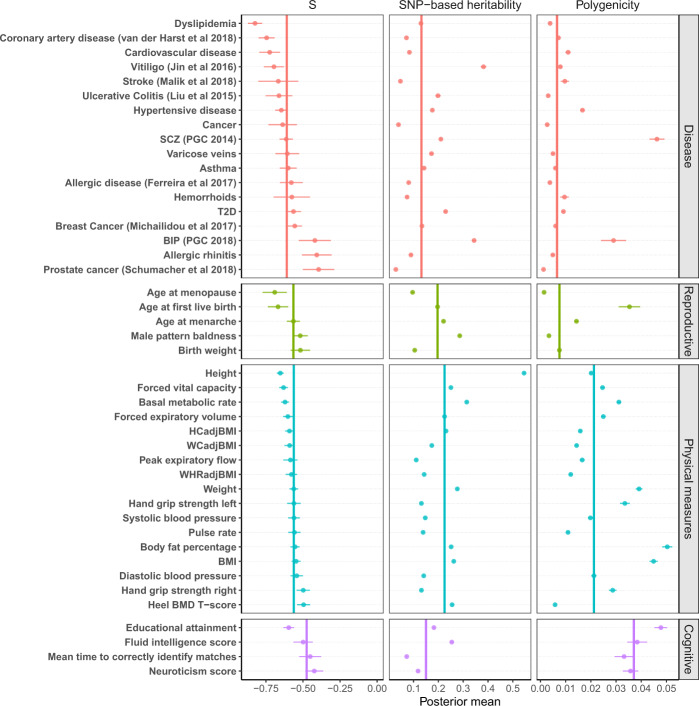

On average across the 44 complex traits (including diseases), 1.8% of the 1.1 million common HapMap3 SNPs explained 18% of the phenotypic variance (Fig. 2 and Supplementary Tables 1, 2). The estimate of

Estimation of the three genetic architecture parameters for 35 traits from the UKB and 9 common diseases from published GWAS.

Shown are the posterior means (dots) and standard errors (horizontal bars) of the parameters for each trait. The colour indicates the UKB trait category that the trait belongs to. The vertical bar shows the median of the estimates across traits in each category.

We used the UKB classification code to classify the 44 traits into four categories related to disease, reproduction, physical measures, and cognition (Supplementary Table 3). The estimates of the genetic architecture parameters varied across traits and appeared to have distinct patterns in different categories (Fig. 2). Physical measures had the highest median SNP-based heritability (0.225), followed by reproductive traits (0.197). The median polygenicity estimate was the lowest for diseases (0.007) and reproductive traits (0.008) and the highest for cognitive traits (0.037). The estimates of polygenicity for psychiatric disorders such as schizophrenia (

To investigate the diversity of genetic architecture in more traits, we applied SBayesS to GWAS summary data from the Neale Lab (http://www.nealelab.is/uk-biobank) for 274 UKB traits, among which 130 passed the convergence test and 110 of these were not included in the analyses above (Supplementary Table 4). The traits that failed to converge tended to have much smaller sample size or

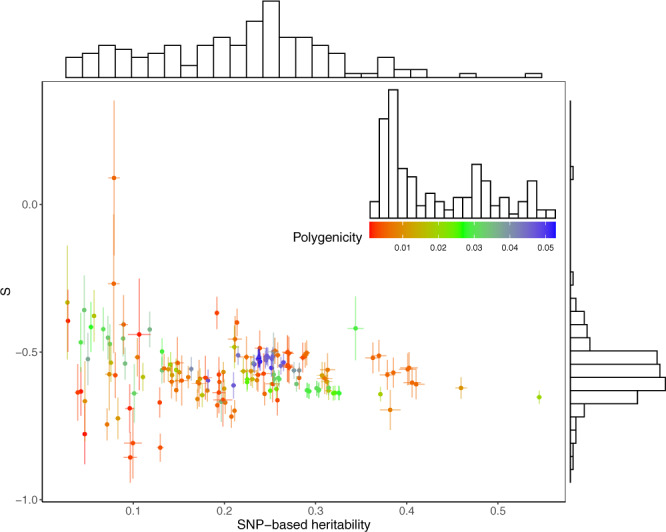

Estimation of the genetic architecture parameters for 155 complex traits.

Shown are the results from the SBayesS analyses using summary data for 130 traits from the Neale Lab and 25 traits from our GWAS analyses and other published studies. The estimated S is plotted against the estimated SNP-based heritability with the histograms showing the marginal distributions of the estimates. Data are presented as posterior means ± posterior standard errors. Colour indicates the estimate of polygenicity for each trait where the scale and distribution are shown in the inset graph.

Although a negative estimate of S is a signature of negative selection, the numeric interpretation of

Repeating the simulation with different values of

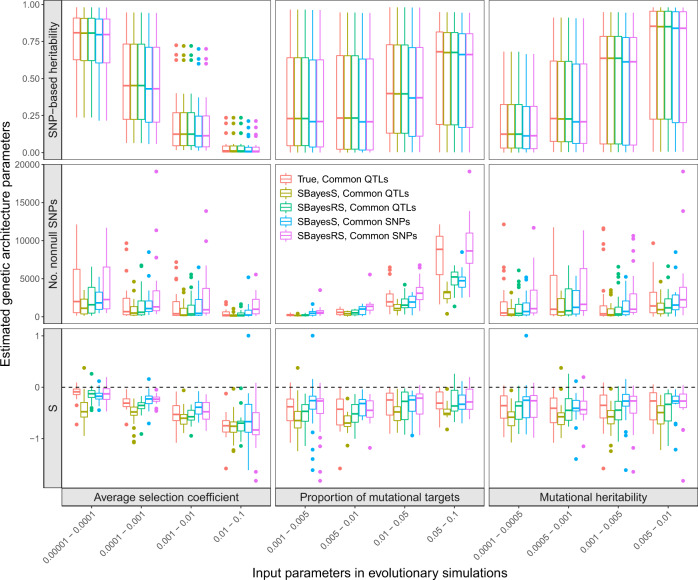

Variational patterns of the estimated genetic architecture parameters under different scenarios of evolutionary simulations.

The selection coefficients followed a mixture distribution, and the Simons et al. pleiotropic model with nt = 1 was used to generate genetic effects (see the “Methods” section). The x-axis shows the values of three input parameters in the evolutionary simulations. The y-axis shows the distribution of the genetic architecture parameter estimates, where the polygenicity parameter is represented by the number of nonnull SNPs for better benchmarking. Colours indicate the following methods: “True, Common QTLs”—parameters computed directly from the simulated genetic effects of all common causal variants; “SBayesS, Common QTLs” (or “SBayesRS, Common QTLs”)—SBayesS (or SBayesRS) estimates using the genotype data of the common causal variants, “SBayesS, Common SNPs” (or “SBayesRS, Common SNPs”)—SBayesS (or SBayesRS) estimates using the genotype data of 36k common SNPs. Each box plot shows the results of 25 independent simulation replicates. The band inside the box is the median, the bottom and top of the box are the first and third quartiles, respectively (Q1 and Q3), and the lower and upper whiskers are Q1–1.5 × IQR and Q3 + 1.5 × IQR, respectively, where IQR = Q3–Q1.

Next, we used a polynomial regression model to associate the evolutionary parameters (

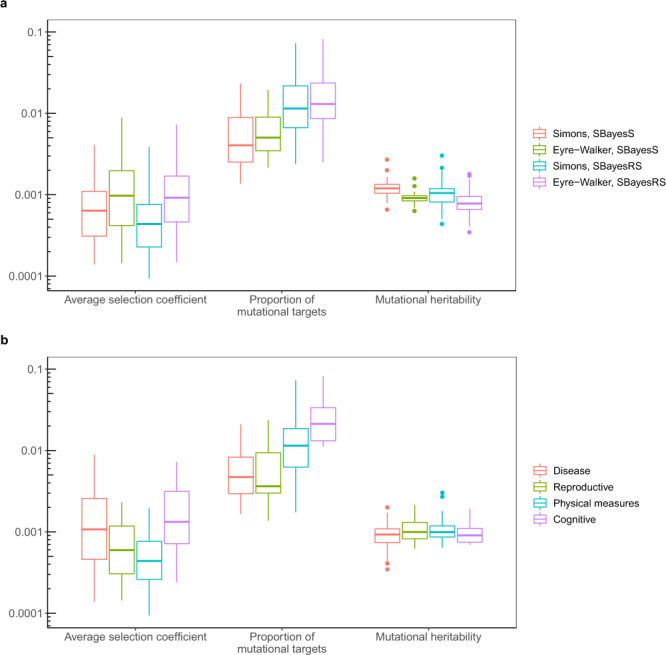

Prediction of the evolutionary parameters for 44 complex traits and diseases based on a negative selection model where selection coefficients followed a mixture distribution.

a Distribution of the predicted evolutionary parameters under different scenarios: methods used for estimating the genetic architecture parameters (SBayesS and SBayesRS) and pleiotropic effect models used for simulations (the Simons et al. and Eyre-Walker model), shown by colours. Each box plot shows the results for 44 complex traits. b Distribution of predicted evolutionary parameters for four trait categories, shown by colours. Each box plot shows the results for a number of traits in a category, with each trait having four results from analyses using different estimation methods and simulation models.

While the predicted

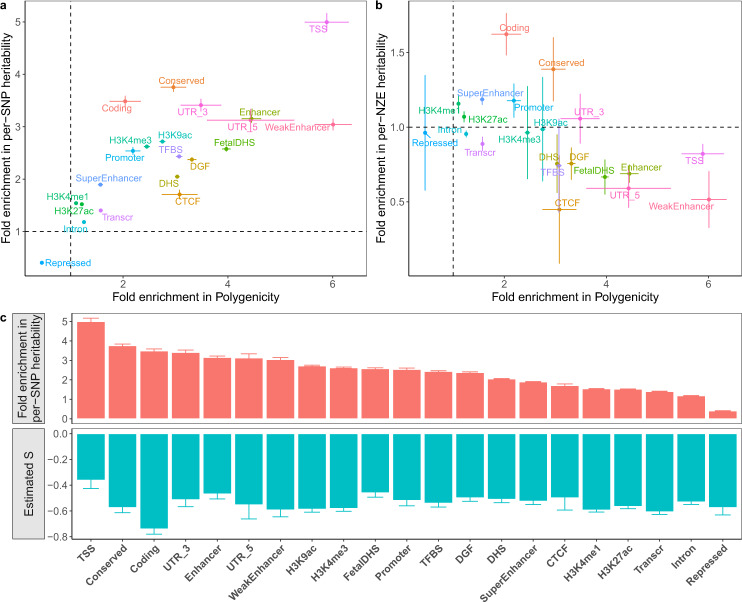

The functional annotation categories used in our analysis were from the LDSC baseline model15. We excluded continuous annotations and annotations with flanking windows, resulting in 21 annotation categories such as the coding, regulatory, repressed and conserved regions (Supplementary Table 5). We applied SBayesS-strat to the 35 UKB traits (including 9 diseases), and combined the parameter estimates across traits for each functional category (see the “Methods” section). Considering the extensive overlaps between annotation categories (Supplementary Fig. 23), we ran SbayesS-strat analysis with a two-component model (SNPs in an annotation category versus the other SNPs) and computed the enrichment of each of the genetic architecture parameters using the SNPs in the focal annotation category in comparison to the genome-wide estimate using all SNPs. The fold enrichment of per-SNP heritability was correlated with that of polygenicity across annotation categories (r = 0.762; Fig. 6a). The per-SNP heritability and polygenicity were enriched in functionally important categories, such as transcription start sites (TSS), 3′- and 5′-UTRs, and conserved, enhancer and coding regions, but depleted in repressed regions. This result suggests that a functional category that explains a greater fraction of heritability tends to have a larger number of nonnull variants, consistent with the findings from a recent study11. However, for some categories, such as coding and conserved regions, the fold enrichment of per-SNP heritability was greater than that of polygenicity, suggesting an enrichment of larger effect sizes in these regions. To distinguish between the contributions of the number and the magnitude of the nonzero effects to

Characterisation of the genetic architecture in 21 functional genomic annotation categories using the two-component SBayesS-strat model.

a Fold enrichment of per-SNP heritability against that of polygenicity. b Fold enrichment of per-NZE (per-nonzero effect) heritability against that of polygenicity. Colours indicate different annotation categories. c Estimated S (green) across annotation categories ranked by per-SNP heritability enrichment (red). Each dot or histogram is the median across 35 UKB traits (including diseases). Each bar indicates the standard error of the mean.

Our estimates of per-SNP heritability enrichment were consistent with those from S-LDSC15,40,41 for most annotation categories (Supplementary Fig. 25). However, S-LDSC reported a much larger enrichment for the conserved region category, followed by the coding region category. This may be due to the different assumptions made in the two methods, i.e., SBayesS-strat assumes a sparse genetic architecture whereas S-LDSC does not explicitly assume a mixture model, as both the coding and conserved regions categories were enriched for the number of nonzero effects and the magnitude of effect sizes (Fig. 6b). Another explanation could be that the SBayesS-strat estimate is from a separate analysis of a focal category at a time conditioning on all the other SNPs with no overlap among categories whereas the S-LDSC estimates are from a joint analysis of all the categories with overlaps.

We have developed an efficient summary-data-based method to estimate the joint distribution of effect sizes and MAF as well as SNP-based heritability, polygenicity and joint SNP effects. By analysing GWAS summary statistics from the public domain, we detected pervasive signatures of negative selection in the genetic architecture for a wide range of complex traits including common diseases (Figs. 2 and 3). Our results support a model of negative selection, that is, most new nonneural mutations are deleterious to fitness such that mutations with larger effects on fitness are more likely to be eliminated or kept at lower frequencies in the population by selection.

Most traits had

Our polygenicity parameter π represents the proportion of SNPs with nonzero effects; this definition has also been used previously13,28,35,44–47. Our forward simulations showed that π is driven by both the mutational target size and selection strength, with increased average selection coefficient resulting in decreased

Since we only detected signatures of negative selection in real traits, our evolutionary simulations focused on the models of negative selection. To investigate the impact of both negative and positive selections, we extended our simulation scenarios by considering two additional positive selection-related parameters: average positive selection coefficient and proportion of beneficial mutational targets (see the “Methods” section). When considering both negative and positive selections in the simulations, we observed more complicated relationships between the genetic architecture and evolutionary parameters (Supplementary Fig. 27), which, however, could still be used for prediction. Our results showed that the predicted

The biologically important categories, such as the TSS, conserved, UTR and coding regions, had the highest enrichment in per-SNP heritability, most of which also had the highest enrichment in polygenicity, whereas the repressed regions were depleted in both parameters (Fig. 6). The concordance in functional enrichment between the two parameters reflects an uneven distribution of the number of causal variants across functional categories, consistent with the finding from prior work11. We further observed enrichment of per-NZE heritability in conserved and coding regions, suggesting larger effect sizes of nonnull SNPs in these regions compared to genome average. It is of note that coding regions showed the largest

There are several limitations in this study. First, our inference on negative selection is based on HapMap3 common SNPs and therefore may not hold for the unobserved rare variants. In fact, we found by forward simulations a weaker magnitude of S in rare variants because the very rare variants were mostly new mutations whose relationship between effect size and MAF had not yet been shaped by selection, which diluted the selection signals from the variants under selection (Supplementary Fig. 29). This suggests that the true S parameter is allelic age dependent and subject to the combined effect of mutation, selection and genetic drift. An apparent change in the effect size–MAF relationship when moving toward low MAF was also reported by Schoech et al.7. Second, independence of chromosomes is assumed in our model. This may not hold if there was non-random mating in the ancestral population. For example, assortative mating would introduce positive correlations between trait-increasing alleles located on different chromosomes, and therefore increase heritability in the equilibrium population, e.g., for height48. Third, our definition of polygenicity is based on the number of SNPs with nonzero effects (mNZ), which may not be an unbiased estimator of the number of causal variants (mC) especially when the causal variants are not observed. For example, mNZ will tend to be smaller than mC if some causal variants are not well tagged by any SNP markers but tend to be larger than mC if they are in high multi-locus LD with a number of SNPs. Thus, our polygenicity estimate should be best used to compare traits using the same set of SNPs, rather than an unbiased estimate of the number of causal variants. Fourth, we did not attempt to predict the evolutionary parameters for functional genomic categories because it would require simulating a genome with functional partitioning. Despite these limitations, our study highlights the impact of negative selection on the genetic architecture across complex traits and in different functional genomic regions. In addition to a better understanding of the genetic architecture, our methods can also be applied to genetic mapping and polygenic risk prediction through the use of the joint SNP effect estimates or the characterised underlying distributions of effect sizes as prior knowledge for other methods49.

Let us consider an individual-level data-based multiple regression model for a GWAS cohort:

When the LD correlations are computed using all SNPs in the GWAS sample, models (1) and (2) are equivalent in terms of posterior inference because the GWAS estimates of SNP effects (b) and LD correlation matrix (B) are sufficient statistics for the joint posterior distribution of β (Supplementary Note). Compared to model (1), model (2) allows us to incorporate LD information from a different reference sample from the GWAS sample for which the individual-level data are often not accessible. Further, it is often not practical to compute and store the entire LD matrix in the memory. Therefore, we used a sparse LD matrix that ignores the small LD correlation estimates due to sampling variation, but still accounted for the sampling variance of LD correlation in the model (Supplementary Note). In our GCTB software13 where SBayesS is implemented, we have developed a parallel computing strategy to facilitate the computation of the LD matrix. Once the LD matrix is computed, it can be used repeatedly in the GWAS summary-data analysis for different traits.

We used MCMC algorithm to generate 50,000 posterior samples (the first 20,000 discarded as burn-in) from the joint posterior distribution of model parameters, based on which statistical inference was made. Details of the MCMC sampling scheme are shown in the Supplementary Note. The posterior mean was used as the point estimator, with the statistical uncertainty quantified by the posterior variance or its square root (posterior standard error), as shown below. We ran four parallel chains with different starting values of the parameters randomly sampled from their prior distributions. Following the method proposed by Gelman and Rubin27, we estimated the posterior variance by

To assess convergence in MCMC, we computed the potential scale reduction statistic

For computational efficiency, we used a sparse LD matrix in the analysis where LD due to sampling variation were set to be zero. To this end, we tested whether LD between each pair of SNPs on the same chromosome is zero in the population when computing the LD correlation matrix using a reference sample. Under the null hypothesis that the true LD in the population is zero, we assume51

In BayesS13, we computed the genetic variance

Following the recently published SBayesR29 model which assumes a mixture of a point mass at zero and multiple normal distributions with different variances, we extended SBayesS to this flexible multi-component mixture model to account for a more complex genetic architecture with a spectrum of very small to very large effect sizes. For each SNP effect, we assume

SBayesS-strat is a two-component SBayesS model that allows the distributions of SNP effects in the focal annotation category, e.g., coding, regulatory and conserved regions, to be different from that in the rest of the genome. Compared to other methods utilising functional annotations, such as S-LDSC52, BayesRC53 and RSS-E54, a unique feature of the annotation-stratified SBayesS (referred to as SBayesS-strat) is that it allows the estimation of S in a specific functional annotation category. Compared to a recently published method, BLD-LDAK-Alpha9, that estimates the S parameter (denoted by α in their model) based on an infinitesimal model, our method accounts for a sparse genetic architecture. In addition to the estimation of per-SNP heritability, polygenicity and S for each category, we also defined per-nonzero-effect (per-NZE) heritability (

We combined the SBayesS-strat estimates across traits by calculating the median fold enrichment for each functional category. We reported the median instead of the mean in order to minimise the impact of outliers, especially for the per-NZE heritability estimate for which the denominator (i.e., the number of nonzero effects in an annotation category) is often estimated with large sampling variance. To account for the phenotypic correlation among the traits, we estimated the effective number of traits (ne) by performing an eigen decomposition on the phenotypic correlation matrix55:

We performed GWAS analyses for 26 quantitative traits and 9 common diseases in the full release of the UKB data using PLINK 1.90 beta56. We used 348,501 unrelated individuals of European ancestry (estimated genetic relatedness from GCTA < 0.05)57 and the imputed data provided by the UKB team16. We filtered HapMap3 SNPs30 with MAF < 0.01, HWE test P value < 1 × 10−6, missing genotype rate > 0.05, or imputation info score < 0.3. We further excluded SNPs in the Human Major Histocompatibility Complex (MHC) region, resulting in a total of 1,124,198 common SNPs for the analysis. The LD correlations in the reference samples were computed based on the effect alleles in the GWAS summary data. For quantitative traits, we standardised phenotypes to mean zero and variance one after removing the outliers (phenotype > 7 SD) and performed rank-based inverse normal transformation (RINT) within each sex group. Prior to GWAS, we pre-adjusted phenotypes by age, sex and first 10 principal components (PCs) provided by the UKB team after RINT if applied. For the publicly available summary statistics, we downloaded the data and matched the SNPs with those in the UKB data after excluding the strand ambiguous SNPs (i.e., A/T or C/G SNPs) in addition to the QC procedures above. For the GWAS summary data from the Neale Lab, we extracted 274 quantitative traits for which the GWAS was performed based on RINT phenotypes in their analysis pipeline.

We used SLiM326 to run evolutionary forward simulations. A large sequence of 100 Mb was simulated, where a proportion of new mutations (πm) that had pleiotropic effects on fitness and trait emerged at random with an average selection coefficient of

A demographic model inferred by Gravel et al.37 with population bottleneck and expansion was used to simulate a population that had undergone selection for 58,000 generations. The simulation started with an ancestral base population of Ne = 7310, which was expanded to 14,474 after 52,080 generations, a long period of neutral burn-in to allow the population reach mutation-drift equilibrium (~1.3 million years assuming 25 years per generation). In generation 55,960, 1861 individuals were split from the base population into a descendant population to mimic the out-of-African dispersal. In generation 57,080, the population size was further reduced to 1032 and then increased with an exponential rate of 0.0038 until generation 58,000, reaching to a final population size of 34,039. In the last generation of selection, we obtained the genotypes of ~2000 unrelated individuals (genomic relationship < 0.05) and computed the LD correlation matrix for all common causal variants and a random sample of 36k common SNPs, a comparable density as the SNPs used in the real trait analysis (1.1 × 106 × 1 × 108/3 × 109 = 36,000). Given the LD matrix and causal effects, we directly simulated the GWAS summary statistics for all variants11,38:

To incorporate positive selection, we specified two more input parameters, i.e., proportion of trait mutations being beneficial (πm,b) and average selection coefficient for the beneficial alleles (

We used a polynomial regression model to predict an evolutionary parameter from the estimates of the genetic architecture parameters for complex traits. The forward simulation data under either the Simons et al.12 or Eyre-Walker3 model with various settings were used as a reference to estimate the associations between an evolutionary parameter (

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Research Reporting Summary linked to this article.

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41467-021-21446-3.

We thank V. Hivert for helpful discussions. This research was supported by the Australian Research Council (DP160101343, DP160101056, and FT180100186), the Australian National Health and Medical Research Council (1107258, 1078901, 1078037, 1113400, and 1177268) and the Westlake Education Foundation. This study makes use of data from dbGaP (accession: phs000788) and UK Biobank Resource (application number: 12505). A full list of acknowledgements for these datasets can be found in the Supplementary Information.

J.Y. and J.Z. conceived the study and designed the experiment. J.Z. derived the analytical methods, conducted all analyses, and developed the software with assistance and guidance from A.X., L.J., L.R.L.-J., Y.W., H.W., Z.Z., L.Y., K.E.K., M.E.G., N.R.W., P.M.V. and J.Y. J.Z. and J.Y. wrote the manuscript with the participation of all authors. All authors reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

This study makes use of individual-level genotype and phenotype data from UK Biobank Resource (application number: 12505) as well as GWAS summary data and functional genomic annotation data from the public domain. UK Biobank: https://www.ukbiobank.ac.ukhttps://www.ukbiobank.ac.uk; GERA: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/projects/gap/cgi-bin/study.cgi?study_id=phs000674.v2.p2; UKB GWAS summary data from the Neale Lab: http://www.nealelab.is/uk-biobank; baseline-LD annotations: https://data.broadinstitute.org/alkesgroup/LDSCORE; HapMap3: https://www.sanger.ac.uk/resources/downloads/human/hapmap3.html. Sparse LD matrix of ~1.1 million HapMap3 SNPs computed from 50,000 unrelated UKB individuals of European ancestry: https://cnsgenomics.com/software/gctb/#Download.

SBayesS, SBayesRS and SBayesS-strat have been implemented in the GCTB (genome-wide complex trait Bayesian analyses) software tool, freely available at http://cnsgenomics.com/software/gctb. Other software used in this study include PLINK 1.90 (https://www.cog-genomics.org/plink2), SLiM3 (https://messerlab.org/slim), S-LDSC (https://github.com/bulik/ldsc), and GCTA (https://cnsgenomics.com/software/gcta).

The authors declare no competing interests.

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

6.

7.

8.

9.

10.

11.

12.

13.

14.

15.

16.

17.

18.

19.

20.

21.

22.

23.

24.

25.

26.

27.

28.

29.

30.

31.

32.

33.

34.

35.

36.

37.

38.

39.

40.

41.

42.

43.

44.

45.

46.

47.

48.

49.

50.

51.

52.

53.

54.

55.

56.

57.

58.