The discovery of topological quantum states marks a new chapter in both condensed matter physics and materials sciences. By analogy to spin electronic system, topological concepts have been extended into phonons, boosting the birth of topological phononics (TPs). Here, we present a high-throughput screening and data-driven approach to compute and evaluate TPs among over 10,000 real materials. We have discovered 5014 TP materials and grouped them into two main classes of Weyl and nodal-line (ring) TPs. We have clarified the physical mechanism for the occurrence of single Weyl, high degenerate Weyl, individual nodal-line (ring), nodal-link, nodal-chain, and nodal-net TPs in various materials and their mutual correlations. Among the phononic systems, we have predicted the hourglass nodal net TPs in TeO3, as well as the clean and single type-I Weyl TPs between the acoustic and optical branches in half-Heusler LiCaAs. In addition, we found that different types of TPs can coexist in many materials (such as ScZn). Their potential applications and experimental detections have been discussed. This work substantially increases the amount of TP materials, which enables an in-depth investigation of their structure-property relations and opens new avenues for future device design related to TPs.

Topological phononic (TP) materials are attracting wide attentions and it is more difficult to seek TP materials compared to electronic materials. Here, the authors present a high-throughput screening and data-driven approach to discover 5014 TP materials and further clarify the mechanism for the occurrence of various TPs.

Over the past decade, topological concepts have made far-reaching impacts on the theory of electronic band structures in condensed matter physics and materials sciences1–3. Thousands of topological electronic materials4–8 were theoretically proposed9–11 and some of them were experimentally verified, such as, topological insulators4–8, Dirac/Weyl semimetals12–16, and nodal-line semimetals17–21. As the counterpart of electrons, phonons22 are energy quanta of lattice vibrations. They make crucial contributions to many physical properties, such as, thermal conductivity, superconductivity, and thermoelectricity, as well as specific heat. Similar to topological electronic nature, the crucial theorems and concepts of topology can be introduced to the field of phonons, called topological phononics (TPs)23–43. In particular, TPs in solid materials are also correlated to some specified atomic lattice vibrations generally within a scale of THz frequency, thereby providing a rich platform for the investigation of various quasiparticles related with Bosons.

TPs have been theoretically or experimentally investigated in solid-state materials. Several theoretical models, including monolayer hexagonal lattices35,36, Kekulé lattice37,38, and one-dimensional (1D) chains39, were discussed. More recently, a number of real materials were predicted to host the Weyl TPs23–29,33, nodal-line TPs 30–34, and nodal-ring phonons32. Single Weyl TPs were predicted in noncentrosymmetric WC-type materials23,25, exhibiting twofold degenerate Weyl points with the ±1 topological charges. In FeSi-type materials, double Weyl TPs were predicted and then experimentally confirmed24,40. In SiO2, the coexisted single and double Weyl TPs were suggested29. In addition to occupying the discrete sites in the reciprocal space as Weyl points, these band crossing points can also continuously form nodal-lines (e.g., in MgB2 (ref. 31) and Rb2Sn2O3 (ref. 33)) or nodal-rings TPs (e.g., in graphene32, bcc C8 (ref. 30), and MoB234). TPs exhibit the typical features of bulk-surface (edge) correspondence, which are rooted in different geometry phases of Hamiltonian. The existence of multiple critical physical phenomena, such as phononic valley Hall effect36, phononic quantum anomalous Hall-like effect, and phononic quantum spin Hall-like effect controlled by multiple-valued degrees of freedom37, are beneficial to TPs’ applications. Because the topologically protected states are immune to backscattering1–3, TPs would be very promising for applications in the abnormal heat transport44,45, and phonon waveguides38, and so on. In addition to the atomic crystals, topological phonons have also been extensively studied in mechanical metamaterials46–50, acoustic systems51–53, and Maxwell frames54–57.

Unlike the topological electronic materials in which one only needs to focus on energy states near the Fermi level, phonons exhibit several distinct properties. First, there are no limits of Pauli exclusion principle. Second, each phonon mode, following Bose–Einstein statistics, can become practically active, due to thermal excitation. Third, phonons are charge neutral and spinless Bosons, which can not be directly influenced by the electric and magnetic fields. Hence, a full frequency analysis for all phononic branches is needed for the study of TPs. To date, a large-scale identification of TP materials remains challenging, because it is far more expensive to compute the phonon band dispersions than to calculate the electronic band structures. Hence, it is certainly more difficult to seek feasible TP materials in a high-throughput (HT) computational manner, as compared with the recent works in topological electronic materials9–11.

Herein, we present an efficient and fully automated workflow that can screen the TP crossings in a large number of solid materials. Our results reveal that TPs extensively exist in phonon spectra of many known materials, which can be classified into two main types of Weyl and nodal-line (ring) TPs. We have elucidated the physical mechanism for the occurrence of Weyl and nodal-line (ring) TPs. Weyl TPs can be found as (1) single TPs in the crystals without the inversion symmetry, and (2) high degenerate TPs in the noncentrosymmetric crystals with the presence of screw rotations. Nodal-line (ring) TPs can be found as individual nodal-line (ring), nodal-link, nodal-chain, and nodal-net TPs in the crystals with PT symmetry, upon the manipulation of the nonsymmorphic symmetry elements (e.g., screw rotation and glide reflection). Among the phononic systems, we have predicted the hourglass nodal-net (HNN) TPs in TeO3, as well as the clean and single type-I Weyl TPs between the acoustic and optical branches in half-Hesuler LiCaAs. We also found that the extensive coexistence of different types of TPs in materials, such as, the coexisted threefold and fourfold degenerate Weyl TPs in BeAu and the coexisted nodal-line and nodal-ring TPs in ScZn.

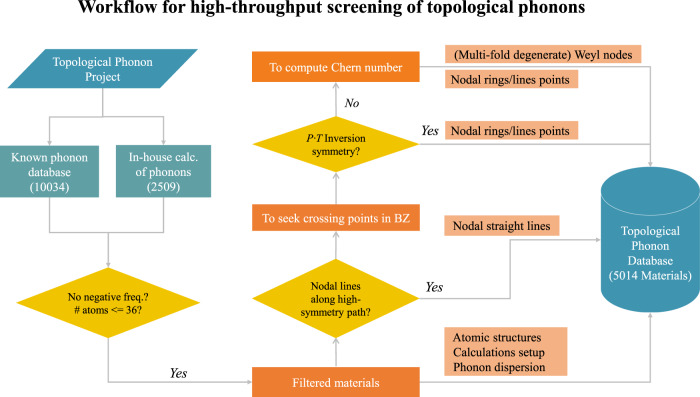

As shown in several prototypical materials23–42, identifying TPs requires several stages of manual selections and subjective human decisions. To enable the TPs discovery in an automatic manner, we present a HT screening and data-driven approach to discover and categorize TPs, as described in Fig. 1, including the following four steps.

The schematic flowchart of high-throughput computational screening on topological phonons.

This workflow is capable of identifying the features of TPs, elucidating details of topology and constructing TPs database by computing and collecting phonons of a variety of solid materials in an automatic manner.

Phonon data collection. To obtain phonon spectra for a large volume of known materials, we first collected 10,000 materials’ force constant data from public phonon database58,59. The data set was further augmented by our in-house computations for over 2000 materials belonging to 58 common structural prototypes. It is well known that the calculated force constants are numerically sensitive to the choices of several parameters, e.g., the supercell size, K-point mesh, and energy cutoff. To guarantee that the predictions are reliable, we filtered out the materials with notable imaginary frequencies (<−0.5 THz) in the whole phononic momentum space.

Nodal straight lines identification. We computed their band dispersions on the automatically generated high-symmetry band paths60. If there exist degenerate phononic bands along high-symmetry paths,we would compute the Berry phase , by an integral of Berry connection (

Crossing points screening. For the rest band paths in the phonon spectra, we systematically scanned 50 points on each band path. In the entire frequency range, we considered the points possessing two adjacent eigenfrequencies < 0.5 THz. For each point, we performed a minimization based on the conjugate gradient algorithm to obtain the local minimum of the frequency difference (Δfreq). The points with Δfreq < 0.2 THz were checked if they possess with Berry phase values of ±π. After optimization, the identified crossing points may go anywhere in the entire reciprocal space. Therefore, we also checked if the points are at or off the high-symmetry paths.

Crossing points assignment. The identified phononic crossing points were then divided into two groups based on the presence of both inversion symmetry (P) and TRS (T) for each material. In a three-dimensional (3D) system with PT symmetries, the Berry curvatures of nondegenerate phononic bands are forced to be zero and the Weyl TPs would not occur in such system. Once the phononic bands at a degenerate point have opposite nonzero Berry phases, such topological nontrivial degenerate points have to occur continuously by forming nodal-line (ring) TPs, due to the continuity of phonon wave function in the 3D momentum space. As a result, when the PT symmetry is present, we just need to seek nodal-lines (rings) off high-symmetry line. In noncentrosymmetic materials, the phonon dispersions possibly form single Weyl or high degenerate Weyl TPs, in addition to nodal-lines (rings) TPs. In order to clarify these three types of TPs, we introduced another formula of Chern number, which can be derived by integrating Berry curvatures of a closed surface61 according to

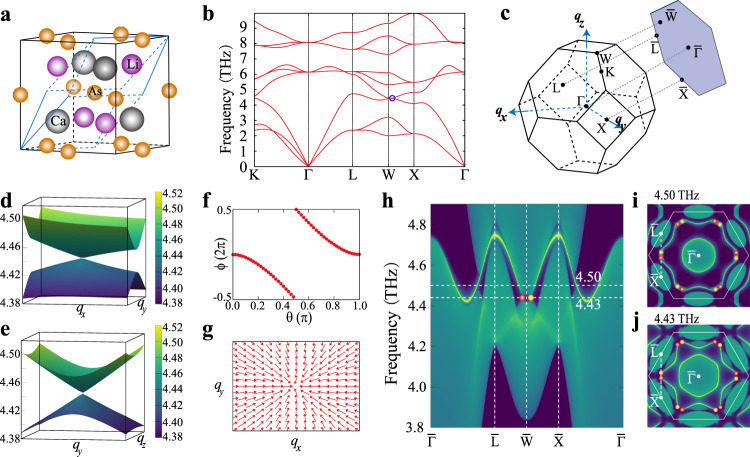

In order to experimentally observe phononic surface states, a TP material is expected to possess distinct Weyl or nodal-line (ring) TPs and possible clean nontrivial surface TPs. For this purpose, we mathematically define the clean TPs for the nontrivial crossing points satisfying two conditions in bulk phonon spectra, (i) the crossing points have to be located at local minima with negligible or zero phononic density of states (DOS; <0.01 states/atom/THz) and (ii) the dispersion at the local minima is sufficiently large (∂E/∂q > 3.0 THz ⋅ Å). On basis of these two criteria, we have filtered 322 clean TP materials (Supplementary Table 5). For instance, single type-I Weyl TPs in LiCaAs are clean, because it does not overlap with the other bulk phonon branches and has a zero phonon density at the frequency of 4.590 THz (Fig. 2i, j).

Phonon dispersion and single Weyl TPs of LiCaAs.

a The unit cell and primitive cell of LiCaAs (space group

In total, our approach revealed that 5014 materials exhibit TPs states (Supplementary Table 1). Among them, we have identified two main categories of nodal-line (ring) and Weyl TP materials. Among nodal-line (ring) TPs (Supplementary Table 2), there are several possible subclasses, including nodal-link, nodal-chain, and nodal-net TPs according to different symmetries. Among Weyl TPs, there are two main subclasses of single Weyl TPs (Supplementary Table 3) and high degenerate Weyl TPs (Supplementary Table 4) according to the degree of phononic band degeneracy. In particular, we note that, different from electronic system, it is impossible to have the intrinsic TP insulators without any tunable external field. This is mainly because the phonon spectrum always preserves the time-reversal symmetry (TRS). The TRS for phonon spectrum was suggested to be broken only in artificial lattices, such as in ionic lattices using Lorentz force35 and magnetic lattices using spin–lattice interactions62. Therefore, we did not attempt to identify the intrinsic topological phonon insulators in our current work.

To understand the occurrence of TPs in various materials and their correlations, we chose to investigate four representative cases, including (1) half-Heusler LiCaAs alloy for single Weyl TPs, (2) superconducting BeAu for high degenerate Weyl TPs, (3) ScZn with the PT symmetries for nodal-line (ring) TPs, and (4) TeO3 with both PT and nonsymmorphic symmetries for HNN TPs. To conveniently analyze their TP states, we use a general k ⋅ p Hamiltonian as follows,

Applying different constraints of crystal and PT symmetries to this Hamiltonian, we can describe various geometries of the phonon crossings.

Half-Heusler compounds AIBIIXV (where A ∈ {Li, Na, K, Rb, Cs}; B ∈ {Mg, Ca, Zn}, and X ∈ {P, As}) with noncentrosymmetric space group F43m (no. 216) have been widely studied 63,64. Since they share similar phonon dispersions, here we focus on the case of LiCaAs. As shown in Fig. 2a, the As atoms are in the 4a

Wyckoff sites, while both Li and Ca are in the 8c sites. At 4.590 THz, the highest longitudinal acoustic (LA) and the lowest transverse optical (TO) branches have a band cross at the

To elucidate the underlaying physics for the type-I Weyl TPs in LiCaAs, we constructed the Hamiltonian from Eq. (1) according to the fact that LiCaAs possesses both the TRS T and the twofold rotational symmetry C2. As shown in Fig. 2d, e, the type-I WPs do not have the tilt term (expressed as d0σ0 in Eq. (1)). Combining T and

This condition implies that the crossing points on the square plane (

High degenerate Weyl points refer to the nontrivial crossings, which have a degeneracy higher than two. Our screening has found the existence of threefold and fourfold nontrivial high degenerate Weyl points in 447 TP materials (see Supplementary Table 4). For threefold degenerate Weyl TPs, the Hamiltonian can be written as H3(k)

∝

q ⋅ S, where q is a wavevector and Si are the rotation generators for spin-1 bosons. Those three bands at the crossing point will have the Chern numbers of +2, 0, and −2 and they are also called “spin-1 Weyl point”24. For fourfold degenerate Weyl TPs, their Hamiltonian can be written as H4(k)~I2⨂(q ⋅ σ), where I2 is the second-order identity matrix and σi(i = x, y, z) are the three Pauli matrices. Those high degenerate Weyl TPs can be regarded as the sum of identical spin-

Among 447 TP materials with high degenerate Weyl TPs, BeAu is a typical noncentrosymmetric superconductor with a critical temperature of 3.2 K (ref. 65). BeAu crystallizes in a cubic B20 structure with the space group of P213 (no. 198). Both Be and Au atoms are located at 4a

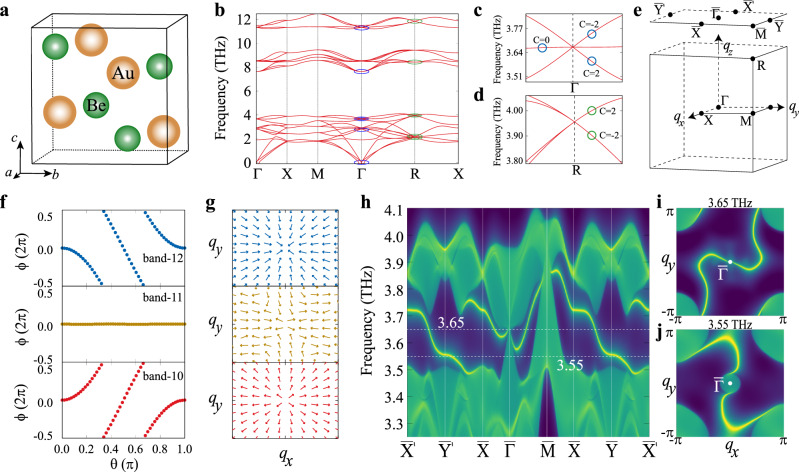

Wyckoff sites (Fig. 3a). The phonon spectrum along the high-symmetry lines in Fig. 3b shows six threefold degenerate Weyl TPs (blue circles at Γ) and six fourfold degenerate Weyl TPs (green circels at R). These high degenerate Weyl TPs are protected by both the lattice symmetries (twofold screw rotations and threefold rotations) and TRS. To determine their topological natures, we calculate the Chern numbers for high degenerate Weyl TPs at both Γ and R in the BZ (Fig. 3c, d). The Chern numbers for threefold degenerate Weyl TPs are −2, 0, and 2, while those are ±2 for fourfold degenerate Weyl TPs. For the Weyl TPs at Γ, we can derive its Wannier center evolutions because of the well-separated bands. The threefold degenerate Weyl TPs in Fig. 3c are contributed from three phonon branche nos. 10, 11, and 12. As shown in Fig. 3f, the Wannier center evolutions for those three branches indicate that both nos. 10 and 12 bands are topologically nontrivial, whereas no. 11 band is trivial. This fact reveals that the threefold degenerate point is similar to a single Weyl point. However, it has a high topological charge of +2 and the corresponding Berry curvatures at qxy plane give the source behaviors at Γ (ω = 3.669 THz), which is protected by the twofold screw rotation axis at Γ in the BZ. The fourfold degenerate Weyl TPs in Fig. 3d are contributed from two doubly degenerate bands, with the Chern numbers, c = ±2. These fourfold degenerate Weyl TPs at R have the topological charge −2, which is also protected by the twofold screw rotation axis at R. Both the threefold and fourfold degenerate Weyl TPs have the opposite topological charges, indicating the conservation of the topological charges for Weyl TPs in the first BZ. Meanwhile, as shown in Fig. 3h, we have derived the topological nontrivial surface TPs along the high-symmetry lines on the (001) surface. Clearly, the topological nontrivial surface states connect both threefold and fourfold degenerate Weyl TPs at

Phonon band structures and surface states for topological high degenerate Weyl TPs in BeAu.

a The crystal structure of BeAu (space group P213 198). b The phonon dispersion along the high-symmetry lines. The blue circles are the threefold degenerate Weyl TPs at Γ and the green circles are the fourfold degenerate Weyl TPs at R. c Threefold degenerate Weyl point of 3.669 THz at Γ. d Fourfold degenerate Weyl TPs of 3.956 THz at R. e Bulk and surface BZ of BeAu. f The Wannier center evolution for three branches 10, 11, and 12 centered at the Γ. g The Berry curvature distributions of three branches 10, 11, and 12 at the centered Γ. h The surface local density of states for (001) surface along the high-symmetry directions. i, j The corresponding surface arcs at 3.65 and 3.55 THz, respectively. Even though BeAu exists in reality, we still found that around Γ point one acoustic branch of BeAu shows the extremely small imaginary frequency, which cannot be removed in our current calculations, possibly due to misconsideration of long range interatomic interaction in the force constant construction or anharmonic effects.

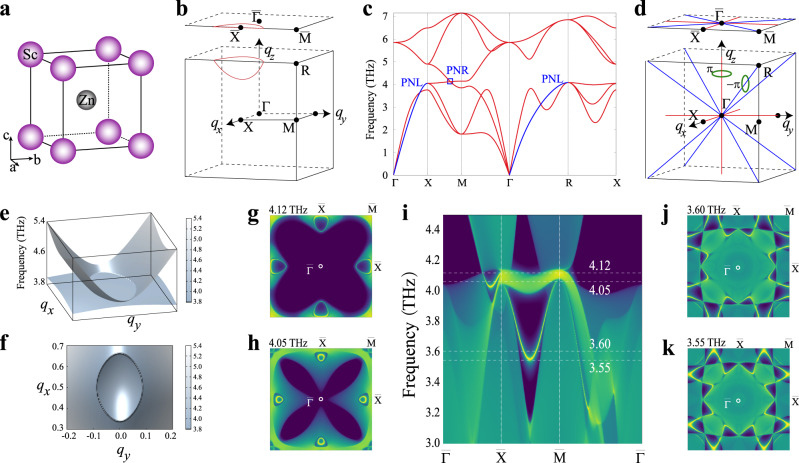

Nodal-line (ring) TPs, formed by continuous phononic band crossings, have also been predicted in phonon spectra of materials30–34. Our results suggest that many materials exhibit such nodal-line (ring) TPs. Here, we introduce ScZn, with a B2 lattice structure (see Fig. 4a), that hosts both nodal-ring and straight line TPs as shown in Fig. 4c.

Phonon band structures and topological properties of phonon of ScZn.

a The crystal structure of ScZn (space group

Firstly, we have noted that the phononic band crossing point between LA and TO on the X–M line of the BZ (Fig. 4c). Unlike the single Weyl TP in LiCaAs, this crossing is not an isolated point, but belongs to a closed ring formed by the continuous linear band crossings, as shown in Fig. 4e, f. The occurrence of the nodal-ring TPs in ScZn can be attributed to the presence of the PT symmetry. Considering the mirror symmetry, ScZn totally hosts six nodal-ring TPs, which are located at the boundary planes of the BZ surrounding the M point in Fig. 4b. Secondly, the nodal-line TPs have been observed along the Γ–X and the Γ–R directions, as shown in Fig. 4c. They can be viewed as countless linear band crossings along the high-symmetry lines and extend through the whole BZ, as illustrated in Fig. 4d, similar to MgB2 (ref. 31). In particular, our further studies reveal that the nodal-ring TPs centered at the M point and the nodal-line TPs along the high-symmetry directions in ScZn are both protected by the PT and mirror symmetries. For inversion symmetry P, we can introduce the inversion operator as

We can simplify this equation into the following relations

At this stage, the eigenvalues of Eq. (2) can be simplified to

Using σz to replace

Therefore, the M-centered nodal-ring TPs can be confined to the plane of qz = π. For nodal-line TPs, the mirrors can also constrain them along one high-symmetry line. Since the nodal-line TPs possess nonzero Berry phases, there exist phononic nontrivial drumhead-like surface states. To elucidate this feature, we have calculated the phonon spectrum on the (001) surface with Green’s function method in Fig. 4i. It shows the nontrivial surface states along the

Our HT calculations further reveal that 114 CsCl-type materials isostructural to ScZn exhibit very similar phonon dispersions (see Supplementary Table 1). All of them host the nodal-line TPs within their acoustic branches along the Γ–X and Γ–M lines, but only some of them host nodal-ring TPs between the LA and TO branches. The existence of the nodal-ring TPs depends on the relative atomic masses of the constituents in compounds. If the atomic masses differ greatly, the nodal-ring TPs at zero acoustic-optical gap will disappear.

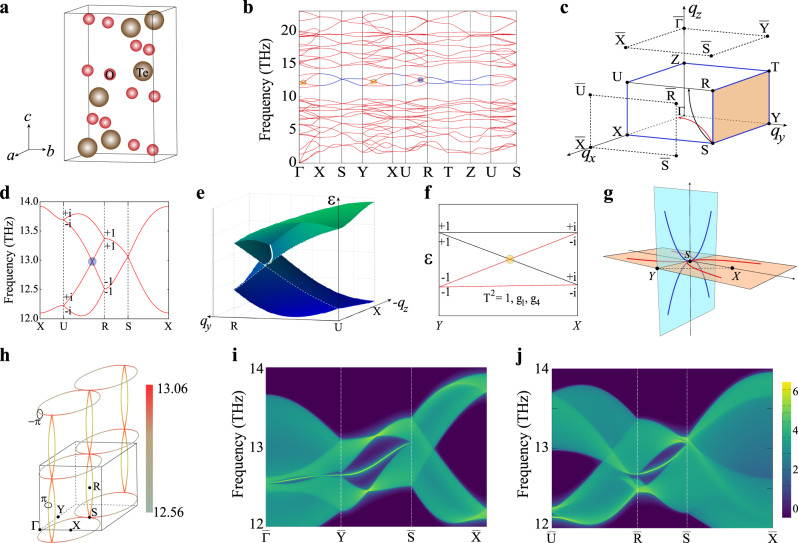

Besides the above nodal-line (ring) TPs associated with the symmorphic symmetries, the nonsymmorphic space groups can produce the symmetry-enforced nodal-line (ring) TPs. Nonsymmorphic symmetries are formed by combining the operations of the point group g and translations t by fraction. TeO3 is such a case, which crystallizes in the Pnna space group (no. 52)67. In its unit cell, there are four Te atoms and each of them forms the TeO6 octahedra (Fig. 5a). In this space group, six nonsymmorphic symmetries are present as follows: g1 = {Mz∣a/2}, g2 = {My∣a/2 + b/2 + c/2}, g3 = {Mx∣b/2 + c/2}, g4 = {C2y∣a/2 + b/2 + c/2}, g5 = {C2z∣a/2}, and g6 = {C2x∣b/2 + c/2}. Our results reveal that TeO3 possesses the HNN TPs in its phonon dispersion in Fig. 5b. To show the key feature of the HNN TPs, here we focus on the four phonon branches (bands 25, 26, 27, and 28) with a frequency range from 12 to 14 THz. These four bands form two nodal-line TPs (marked in blue in Fig. 5b) along the boundaries of the BZ (Fig. 5c). The occurrence of those nodal-line TPs are protected by the crystal symmetries. By combining the TRS T and g1 = {Mz∣a/2}, the lattice momentum can be transformed to

Hourglass nodal-net TPs of TeO3.

a The unit cell of TeO3 (space group Pnna 52). b The phonon dispersion of TeO3. c The bulk BZ and the (001) and (100) surface BZs. Both the red and black arrows denote the hourglass nodal-line TPs, whereas the blue lines along the BZ boundary represent the twofold degenerate nodal-line TPs. All points on the qy = π plane are twofold degenerate nodal points (called twofold degenerate nodal surface), as shown in the yellow plane. d The phonon spectrum along X–U–R–S–X at the qyz plane. The eigenvalues of {Mx∣b/2 + c/2} are given at both U and R points. e The 3D phonon dispersions at the qyz plane. The solid white line represents the hourglass nodal line on which any point represents a hourglass nodal point. f The phononic hourglass nodal dispersions protected by g1 and g4. The eigenvalues of {Mz∣a/2} are given at both Y and X points in the BZ. g Hourglass nodal chains (HNCs) at the qxy plane (red solid lines) and at the qyz plane (blue solid lines). Both these HNCs connect to each other only at the S point to form an hourglass nodal net (HNN) in the extended BZ. h The shape of the HNN in the three-dimensional view. Two black circles are used to calculate the Berry phase of the HNCs and the color represents the energy dispersion of the HNN in THz. i, j The phononic surface states along the high-symmetry lines for the (001) and (100) surfaces, respectively.

It needs to be emphasized that the hourglass nodal points (Fig. 5b) are protected by crystal symmetries. Here, we focus on the hourglass nodal point along the U–R line in qx = π plane (XURS) to elucidate the role of nonsymmorphic symmetries. For the operation g3 = {Mx∣b/2 + c/2}, the eigenvalues are g±(qy, qz) =

Furthermore, the topological nontrivial surface states have been calculated on the (001) and (100) surfaces. Due to the co-dimension rule71, the surface states of the HNC on qz = 0 plane can be obtained on the (001) surface, whereas the surface states of the HNC on the qx = π plane emerge on the (100) surface. As the feature of nodal rings, the drumhead-like surface states can be observed inside or outside the projected region of HNCs, which are determined by the region with nonzero Berry phase32. As shown in Fig. 5i, j, the nontrivial surface states occurs outside the projected HNC on the (001) surface (Fig. 5i), while the drumhead-like surface states appear inside the HNC on the (100) surface (Fig. 5j). HNNs are protected by the nonsymmorphic symmetry and can be extremely stable. Due to the diversity of crystal symmetries, more interesting topological phonon nodal lines or rings can be expected.

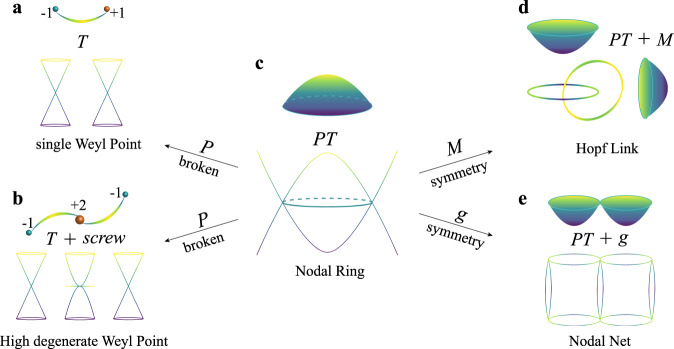

From our HT analysis, we have systematically classified those TP materials into two main categories of Weyl TPs and nodal-line (ring) TPs. Nodal-line (ring) TPs accounted for the largest number of TPs. Among 5014 TP materials, 4978 materials exhibit nodal-line (ring) TPs (in Supplementary Tables 3–5). Figure 6 shows the schematic relations between different types of TPs. As shown in Fig. 6c, nodal-ring TPs can be visualized as continuous crossings of two phononic bands forming a closed loop. Nontrivial drumhead-like surface states, the key feature of topological nature, can be observed when the bulk nodal-ring TPs are projected onto a given surface. These nodal-line (ring) TPs can further evolve into various nodal-link, nodal-chain, or nodal-net TPs, if some crystal symmetries (e.g., mirror or screw symmetries) are combined with the PT symmetry. Here, we elucidate the evolution of cases of the nodal-link and nodal-net TPs. Once the mirror symmetry (M) is added into the PT symmetry, it is possible to obtain various nodal-link TPs. When the crystal hosts two noncoplanar nodal rings protected by two mirrors, two perpendicular nodal rings can pass through the inside of each other and form the Hopf-link TPs by hooking each other, as shown in Fig. 6d. The Hopf-link semimetal states of Fermions have been predicted in Co2MnGa (ref. 72) and the phononic counterpart can also be realized. Once the nonsymmorphic symmetry (g) is combined with the PT symmetry, it is possible to obtain various nodal-net TPs, comprised by continuous nodal-line (ring) TPs. As discussed in TeO3, the nonsymmorphic symmetry (g) can induce the hourglass nodal points, which can form the nodal chain in the extended BZ. Those HNCs share the same vertex with the one in the vertical plane and the HNN can be obtained as shown in Fig. 6e. Currently, we have identified 15 HNN TP materials (Supplementary Table 6). HNN and Hopf-link TPs still exhibit the drumhead-like surface states that are similar to nodal-ring TPs (Fig. 6d, e). Moreover, due to the diversity of both g and M symmetries, more interesting and nontrivial TPs forming by nodal-line (ring) TPs can be discovered.

The schematic relations between different types of TPs.

a Single Weyl TPs in the open arc states. b High degenerate Weyl TPs in the arc surface states. c Nodal-ring (line) TPs in drumhead-like surface states. d Hopf-link TPs in nontrivial surface states. e Nodal-net TPs (e.g., HNN) and their corresponding drumhead-like surface states.

Furthermore, these nodal-line (ring) TPs can be split into Weyl TPs once its P symmetry is broken. Considering the degenerate degree of the nontrivial crossings, Weyl TPs can be categorized into single Weyl TPs (see Fig. 6a) and high degenerate Weyl TPs (see Fig. 6b). The single Weyl TPs can appear at arbitrary momentum positions, while the high degenerate Weyl TPs must stay at the high-symmetry points protected by the screw symmetry. When the single Weyl TPs are projected onto the surface, one open arc will connect those TPs with opposite charge, as shown in Fig. 6a. Due to the high topological charge feature of high degenerate Weyl TPs, multiple open arcs can be observed, which originate from the projected Weyl nodes, as shown in Fig. 6b. For instance, in BeAu, the projected Weyl node of the threefold degenerate Weyl TPs is connected by two open arc states. Interestingly, our calculations predicted 36 materials only for single Weyl TPs (Supplementary Table 2), 463 materials for mixed single Weyl TPs and nodal-line (ring) TPs, and 266 materials for mixed single Weyl, high degenerate Weyl and nodal-line (ring) TPs (Supplementary Table 4), and 181 materials for mixed high degenerate Weyl and nodal-ling (ring) TPs.

When a large set of TP materials data is available, one can expect a variety of new phenomena by manipulating chemistry and structure. Therefore, the researches on TPs certainly deserve to be exploited further.

First, those TP materials can be modulated by the pseudospins36,73 and pseudo-SOC74,75 from the crystalline symmetry and pseudoangular momenta. Phonon Hall effect62,76,77 has been experimentally observed in a paramagnetic insulator, which can be applied to ballistic thermal transport35 and Berry-phase-induced heat pumping78. When the P symmetry is broken, a pair of valley polarized boundary states with a locked valley-momentum can lead to the phonon quantum valley Hall effect36, with potential applications as the phonon valley filter79, phononic antennas80, and negative refractive index materials66. When the TRS is broken, the phonon quantum anomaly Hall effect (QAHE) can be realized by introduction of ionic lattices by the Lorentz force on charge ions35,81, magnetic lattices by the Raman-type spin–lattice interaction35,62, or a Coriolis/magnetic field46,82. The phonon QAHE hosts the one-way edge states which are immune to scattering from defects, and this unique state can be used for novel phonon devices, such as phonon diodes and waveguides38,46,83,84, acoustic delay lines85, thermal rectification44,86–88, and dissipationless phononic circuits38,89,90.

Second, TPs can also enhance the thermoelectric properties of materials. The thermoelectric performance is determined by the thermal power of merit,

Third, TPs can be physically detected at the whole phonon spectrum by using the techniques, such as infrared spectroscopy95, x-ray scattering96, Raman techniques97, and inelastic neutron scattering98,99. Recently, two inelastic x-ray scattering studies have been applied to detect the topological phonons in FeSi and MoB2 (refs.34,40). However, it is far more challenging to characterize the surface phonons because X rays have only a penetration depth of the micron scale. For the surface phonons, several techniques, such as helium scattering100, terahertz polarimetry101,102, and high-resolution electron energy loss spectroscopy (EELS)103,104, can be applied. In particular, the lattice vibrations of

In summary, we have developed a HT and data-driven approach to evaluate the TPs in over 10,000 materials, using the existing phononic database and our in-house calculations. Our screening suggests that TP states are universally present, highlighting extensive possibilities for realizing TPs in a variety of materials toward different potential applications. We expect more topological bulk phonons and nontrivial edge states to be detected by experiments in near future. As such, many exciting phenomena, such as topological superconductivity and high thermoelectricity, may be realized by utilizing the topological phonons in those identified TP materials.

All DFT calculations have been performed by Vienna ab initio simulation package, based on the projector augmented wave potentials and the generalized gradient approximation within the Perdew-Burke-Ernzerhof for the exchange correlation treatment. The force constants downloaded from the PHONONPY database were calculated by the finite displacement method. For the in-house phonon calculations, we used the density function perturbation theory. We performed the geometry optimization of the lattice constants by minimizing the forces within 0.001 eV/Å. The cutoff energy for the expansion of the wave function into the plane waves was set to 1.5 times of the ENMAX in the POTCAR. For the topological analysis, we used the conjugate gradient method in SciPy107 to get the crossings, and calculated the Berry phase and Chern number to identify the nontrivial topological natures. To determine the topological charge, the Wilson-loop method108,109 was chosen. A sphere centered at a WP was sliced into independent orbitals by a constant polar angle θ and the evolution of Wannier centers (phase factor ϕ) on orbitals can give topological charges of WPs. For the surface DOS, we used force constants as tight-binding parameters to construct surface and bulk Green’s functions, and the imaginary part of the Green’s function produces the DOS110,111.

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41467-021-21293-2.

Work at IMR was supported by the National Science Fund for Distinguished Young Scholars (grant number 51725103), by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant number 51671193), by the Science Challenging Project (grant number TZ2016004), and by major research project 2018ZX06002004. Work at UNLV is supported by Q.Z.’s startup grant. All calculations have been performed on the high-performance computational cluster in Shenyang National Park and XSEDE (TG-DMR180040).

X.-Q.C. proposed this idea, and both X.-Q.C. and Q.Z. designed the research. J.X. Li, J.X. Liu, M.F.L., L.W., R.H.L., Y.C., D.Z.L., Q.Z., and X.-Q.C. performed and analyzed the calculations and contributed to interpretation and discussion of the data. S.A.B., Q.Z., J.X. Li and X.-Q.C. coded the online topological phonon database. X.-Q.C., J.X. Li, and Q.Z. wrote the manuscript. All authors discussed this manuscripts.

We have provided a Supplementary Material including 14,248 pages and 5014 figures to classify all 5014 TP materials according to the geometrical character and the Berry phases of topological nodal points (Weyl node, Dirac node, and high degenerate nodal points) and nodal-line (ring) TPs. Each material entry includes the spatial information of the points (e.g., x, y, z coordinates, frequencies, modes, and band paths), and multiplicity, degeneracy, and topological charges to each phononic band crossing points. These data, together with the interactive visualization of atomic structures and phonon band dispersion, are also available, if requested. In addition, we have constucted the corresponding online database, available at www.phonon.synl.ac.cn or https://tpdb.physics.unlv.edu/.

In order to effectively and conveniently analyze topology of phonons, we developed an HT-TPHONON code to automate all processes (as shown in Fig. 1) and connect them with the DFT calculations based on Python scripting. All codes used in this work are either publicly available or available from the authors upon reasonable request.

The authors declare no competing interests.

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

6.

7.

8.

9.

10.

11.

12.

13.

14.

15.

16.

17.

18.

19.

20.

21.

22.

23.

24.

25.

26.

27.

28.

29.

30.

31.

32.

33.

34.

35.

36.

37.

38.

39.

40.

41.

42.

43.

44.

45.

46.

47.

48.

49.

50.

51.

52.

53.

54.

55.

56.

57.

58.

59.

60.

61.

62.

63.

64.

65.

66.

67.

68.

69.

70.

71.

72.

73.

74.

75.

76.

77.

78.

79.

80.

81.

82.

83.

84.

85.

86.

87.

88.

89.

90.

91.

92.

93.

94.

95.

96.

97.

98.

99.

100.

101.

102.

103.

104.

105.

106.

107.

108.

109.

110.

111.