Structure-forming systems are ubiquitous in nature, ranging from atoms building molecules to self-assembly of colloidal amphibolic particles. The understanding of the underlying thermodynamics of such systems remains an important problem. Here, we derive the entropy for structure-forming systems that differs from Boltzmann-Gibbs entropy by a term that explicitly captures clustered states. For large systems and low concentrations the approach is equivalent to the grand-canonical ensemble; for small systems we find significant deviations. We derive the detailed fluctuation theorem and Crooks’ work fluctuation theorem for structure-forming systems. The connection to the theory of particle self-assembly is discussed. We apply the results to several physical systems. We present the phase diagram for patchy particles described by the Kern-Frenkel potential. We show that the Curie-Weiss model with molecule structures exhibits a first-order phase transition.

Structure-forming systems, such as chemical reaction networks, are usually described with the grand-canonical ensemble, but this may be inaccurate for small-sized systems. Here, the authors propose a canonical ensemble approach for closed structure-forming systems, showing its application to physical problems including the self-assembly of soft matter.

Ludwig Boltzmann defined entropy as the logarithm of state multiplicity. The multiplicity of independent (but possibly interacting) systems is typically given by multinomial factors that lead to the Boltzmann–Gibbs entropy and the exponential growth of phase space volume as a function of the degrees of freedom. In recent decades, much attention was given to systems with long-range and coevolving interactions that are sometimes referred to as complex systems1. Many complex systems do not exhibit an exponential growth of phase space2–5. For correlated systems, it typically grows subexponentially6–14, systems with superexponential phase space growth were recently identified as those capable of forming structures from its components5,15. A typical example of this kind are complex networks16, where complex behavior may lead to ensemble inequivalence17. The most prominent example of structure-forming systems are chemical reaction networks18–20. The usual approach to chemical reactions—where free particles may compose molecules—is via the grand-canonical ensemble, where particle reservoirs make sure that the number of particles is conserved on average. Much attention has been given to finite-size corrections of the chemical potential21,22 and nonequilibrium thermodynamics of small chemical networks23–26. However, for small closed systems, fluctuations in particle reservoirs might become nonnegligible and predictions from the grand-canonical ensemble become inaccurate. In the context of nanotechnology and colloidal physics, the theory of self-assembly27 gained recent interest. Examples of self-assembly include lipid bilayers and vesicles28, microtubules, molecular motors29, amphibolic particles30, or RNA31. The thermodynamics of self-assembly systems has been studied, both experimentally and theoretically, often dealing with particular systems, such as Janus particles32. Theoretical and computational work have explored self-assembly under nonequilibrium conditions33,34. A review can be found in Arango-Restrepo et al.35.

Here, we present a canonical approach for closed systems where particles interact and form structures. The main idea is to start not with a grand-canonical approach to structure-forming systems but to see within a canonical description which terms in the entropy emerge that play the role of the chemical potential in large systems. A simple example for a structure-forming system, the magnetic coin model, was recently introduced in Jensen et al.15. There n coins are in two possible states (head and tail), and in addition, since coins are magnetic, they can form a third state, i.e., any two coins might create a bond state. The phase space of this model, W(n), grows superexponentially, . We first generalize this model to arbitrary cluster sizes and to an arbitrary number of states. We then derive the entropy of the system from the corresponding log multiplicity and use it to compute thermodynamic quantities, such as the Helmholtz free energy. With respect to Boltzmann–Gibbs entropy, there appears an additional term that captures the molecule states. By using stochastic thermodynamics, we obtain the appropriate second law for structure-forming systems and derive the detailed fluctuation theorem. Under the assumption that external driving preserves microreversibility, i.e., detailed balance of transition rates in quasi-stationary states, we derive the nonequilibrium Crooks’ fluctuation theorem for structure-forming systems. It relates the probability distribution of the stochastic work done on a nonequilibrium system to thermodynamic variables, such as the partial Helmholtz free energy, temperature, and size of the initial and final cluster states. Finally, we apply our results to several physical systems: we first calculate the phase diagram for the case of patchy particles described by the Kern–Frenkel potential. Second, we discuss the fully connected Ising model where molecule formation is allowed. We show that the usual second-order transition in the fully connected Ising model changes to first-order.

To calculate the entropy of structure-forming systems, we first define a set of possible microstates and mesostates. Let us consider a system of n particles. Each single particle can attain states from the set

Now assume that particles can also form larger clusters up to a maximal size, m. Consider m as a fixed number, m ≤ n. Generally, clusters of size j have states

Now consider a mesoscopic scale, where the mesostate of the system is given only by the number of clusters in each state

The Boltzmann entropy36 of this mesostate is given by

The number of microstates giving the same mesostate can be expressed as the product of configurations with the same state for each

As an example, consider the case of four particles. First, we look at free particles that attain states

For example, a microstate (x(2)(2, 1), x(2)(2, 1), x(2)(4, 3), x(2)(4,3)) is the same as the first microstate because we just relabel 1↔2 and 3↔4. In summary, the multiplicity corresponding to

In the remainder, we denote thermodynamic quantities per particle by calligraphic script and total quantities by normal script. We express the entropy per particle as

Up to now, we assumed an infinite range of interaction between particles, which is unrealistic for chemical reactions, where only atoms within a short range form clusters. A simple correction is obtained by dividing the system into a fixed number of boxes: particles within the same box can form clusters, particles in different boxes cannot. We begin by calculating the multiplicity for two boxes. For simplicity, assume that they both contain n/2 particles. The multiplicity of a system with two boxes,

Note that the entropy of structure-forming systems is both additive and extensive in the sense of Lieb and Yngvason37. It is also concave, ensuring the uniqueness of the maximum entropy principle. For more details and connections to axiomatic frameworks, see Supplementary Discussion.

We now focus on the equilibrium thermodynamics obtained, for example, by considering the maximum entropy principle. Consider the internal energy

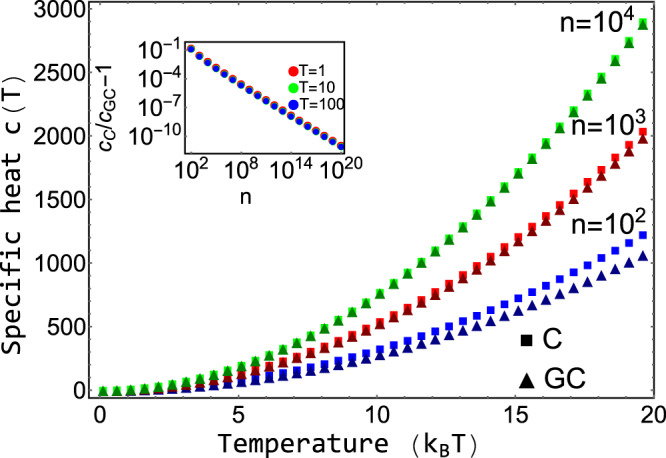

To compare the presented exact approach with the grand-canonical ensemble, consider the simple chemical reaction, 2X⇌X2. Without loss of generality, assume that free particles carry some energy, ϵ. We calculate the Helmholtz free energy for both approaches in Supplementary Information. In Fig. 1, we show the corresponding specific heat,

Specific heat, c(T), for the reaction 2X⇌X2 for the presented canonical approach with an exact number of particles in comparison to the grand-canonical ensemble.

The specific heat for the canonical ensemble (C) is drawn by squares, and the specific heat for the grand-canonical ensemble (GC) is drawn by triangles. n denotes the number of particles. For small systems the difference of the approaches becomes apparent. The inset shows the ratio of the specific heat calculated from the exact approach to the one obtained from the grand-canonical ensemble, cC/cGC − 1. For large n the quantity decays to zero for any temperature.

In many applications, the number of energetic configurations for each cluster size is so large that one is only interested in the distribution of cluster sizes. For this case, it is possible to formulate an effective theory considering contributions from all configurations that is known as the theory of self-assembly. For an overview, see Likos et al.27.

To compute the free energy in terms of the cluster-size distribution, we define the latter as

We now apply the results obtained in the previous section to several examples of structure-forming systems. We particularly focus on how the presence of mescoscopic structures of clustered states leads to the macroscopic physical properties. In the presence of structure formation, there exists a phase transition between a free particle fluid phase and a condensed phase, containing clusters of particles. This phase transition is demonstrated in two examples.

The first example on soft-matter self-assembly describes the process of condensation of one-patch colloidal amphibolic particles. This condensation is relevant in applications in nanomaterials and biophysics. The second example covers the phase transition of the Curie–Weiss spin model for the situation where particles form molecules. In Supplementary Information, we discuss the additional examples of a magnetic gas and a size-dependent chemical potential.

Recently, the theory of soft-matter self-assembly has successfully predicted the creation of various structures of colloidal particles, including clusters of Janus particles32, polymerization of colloids38, and the crystallization of multipatch colloidal particles39. Kern and Frenkel40 introduced a simple model to describe the self-assembly of amphibolic particles with two-particle interactions. rij denotes a unit vector connecting the centers of particles i and j, rij is the corresponding distance, and ni and nj are unit vectors encoding the directions of patchy spheres. The Kern–Frenkel potential was defined as

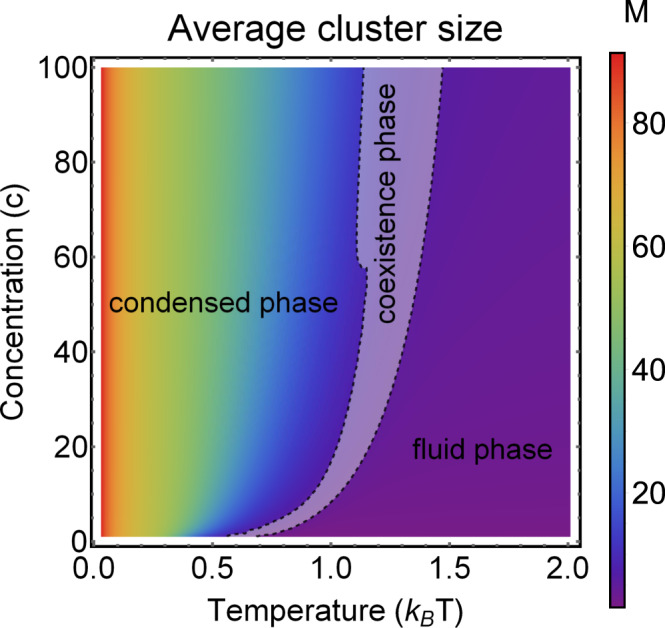

Phase diagram for the self-assembly of patchy particles for n = 100 particles.

The average cluster size (M) as a function of temperature (T) and concentration (c) is seen. The cluster size is given by the color and ranges from M = 0 (purple) to M = 100 (red). We observe three phases: the liquid and condensed phase are divided by a coexistence phase (gray area). Coexistence is characterized by a bimodal distribution that can be detected with a shift in the bimodality coefficient.

To discuss an example of a spin system with molecule states, consider the fully connected Ising model43–46 with a Hamiltonian that allows for possible molecule states

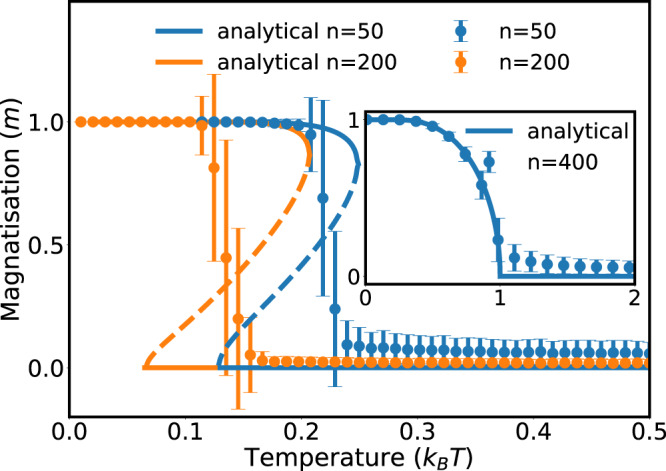

Magnetization of the fully connected Ising model with molecule states for n = 50 and n = 200 particles, for a spin–spin coupling constant, J = 1.

Results of the mean-field approximation (solid lines) are in good agreement with Monte Carlo simulations (symbols). Errorbars show the standard deviation of the average value obtained from 1000 independent runs of the simulations (see Supplementary Information for more details). The inset shows the well-known result for the fully connected Ising model without molecule states. Without molecule formation, we observe the usual second-order transition. With molecules, the critical temperature decreases with the number of particles and the phase transition becomes first-order.

Consider an arbitrary nonequilibrium state given by

Let us now consider a stochastic trajectory, x(τ) = (i(τ),j(τ)), denoting that at time τ, the particle is in state

The time-reversed trajectory is

If we start in an equilibrium distribution with j(τ = 0) = j0 and the reverse experiment also starts in an equilibrium distribution with

We presented a straightforward way to establish the thermodynamics of structure-forming systems (e.g., molecules made from atoms or clusters of colloidal particles) based on the canonical ensemble with a modified entropy that is obtained by the proper counting of the system’s configurations. The approach is an alternative to the grand-canonical ensemble that yields identical results for large systems. However, there are significant deviations that might have important consequences for small systems, where the interaction range becomes comparable with system size. Note that our results are valid for large systems (in the thermodynamic limit) as well as small systems at nanoscales. We showed that fundamental relations such as the second law of thermodynamics and fluctuation theorems remain valid for structure-forming systems. In addition, we demonstrated that the choice of a proper entropic functional has profound physical consequences. It determines, for example, the order of phase transitions in spin models.

We mention that we follow a similar reasoning as has been used in the case of Shannon’s entropy: originally, Shannon’s entropy was derived by Gibbs in the thermodynamic limit using a frequentist approach to statistics (probability is given by a large number of repetitions). However, once the formula for entropy had been derived, its validity was extended beyond the thermodynamic limit, which corresponds to the Bayesian approach. It has been shown, e.g., by methods of stochastic thermodynamics, that the formula for the Shannon’s entropy and the laws of thermodynamics remain valid for systems of arbitrary size (with the exception of systems with quantum corrections) and arbitrarily far from equilibrium47. In this paper, we follow the same type of reasoning for the case of structure-forming systems.

Typical examples where our results apply are chemical reactions at small scales, the self-assembly of colloidal particles, active matter, and nanoparticles. The presented results might also be of direct use for chemical nanomotors51 and nonequilibrium self-assembly35. A natural question is how the framework can be extended to the well-known statistical physics of chemical reactions23–26 where systems are composed of more than one type of atom.

Unsupported media format: /dataresources/secured/content-1765946610551-00b124d0-db6d-4af9-bdbb-47e11d5c781f/assets/41467_2021_21272_MOESM3_ESM.zip

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41467-021-21272-7.

The authors acknowledge support from the Austrian Science fund Projects I 3073 and P 29252 and the Austrian Research Promotion agency FFG under Project 857136. The authors would like to thank Tuan Pham for helpful discussions.

J.K., R.H., and S.T. conceptualized the work, S.D.L. performed the computational work, and all authors contributed to analytic calculations and wrote the paper.

Source Data are provided with this paper. All relevant data are available at: https://github.com/complexity-science-hub/Thermodynamics-of-structure-forming-systems.

The authors declare no competing interests.

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

6.

7.

8.

9.

10.

11.

12.

13.

14.

15.

16.

17.

18.

19.

20.

21.

22.

23.

24.

25.

26.

27.

28.

29.

30.

31.

32.

33.

34.

35.

36.

37.

38.

39.

40.

41.

42.

43.

44.

45.

46.

47.

48.

49.

50.

51.