Exploring material magnetization led to countless fundamental discoveries and applications, culminating in the field of spintronics. Recently, research effort in this field focused on magnetic skyrmions – topologically robust chiral magnetization textures, capable of storing information and routing spin currents via the topological Hall effect. In this article, we propose an optical system emulating any 2D spin transport phenomena with unprecedented controllability, by employing three-wave mixing in 3D nonlinear photonic crystals. Precise photonic crystal engineering, as well as active all-optical control, enable the realization of effective magnetization textures beyond the limits of thermodynamic stability in current materials. As a proof-of-concept, we theoretically design skyrmionic nonlinear photonic crystals with arbitrary topologies and propose an optical system exhibiting the topological Hall effect. Our work paves the way towards quantum spintronics simulations and novel optoelectronic applications inspired by spintronics, for both classical and quantum optical information processing.

Control of effective magnetization textures like skyrmions is limited by the thermodynamic stability in current materials. Here, the authors propose a 3D nonlinear photonic crystal to emulate 2D spin transport phenomena with excellent controllability.

Exploring the physics of material magnetization has long been a focal point of both fundamental science and technological advances. The study of various magnetic phases such as spin ice1 and spin glass2 unveiled novel fundamental phenomena, e.g., magnetic monopoles3, while giant magneto-resistance4 and spin currents5 facilitated applications of magnetic information transfer and storage, giving birth to the field of spintronics6.

A recent focus in this field is on magnetic skyrmions7,8: 3D topological defects in 2D magnetization textures, which are robust to disorder and can be driven in an energy-efficient manner9, making them excellent candidates for memory applications and information processing10. Skyrmions can also be applied to control spin transport through the topological Hall effect11–13: the deflection of a spin-1/2 particle due to its interaction with a topologically nontrivial magnetization.

Although conducting spin transport experiments is readily achievable, performing them under arbitrary magnetization conditions is difficult, since both natural and artificial magnetic materials are restricted to thermodynamically stable phases14,15. Likewise, exact control over spin currents often requires cryogenic temperatures and external control fields, which may influence the system Hamiltonian16,17. As such, utilizing more controllable physical systems to implement the required interaction may be of great importance, both for exploring the system dynamics and for discovering new effects and applications.

For example, the quantum Hall effect18 was successfully simulated using systems the likes of cold neutral atoms19,20 and electromagnetic waves21,22 by virtue of artificial gauge fields23–25. In optics, wherein fabrication capabilities allow a high degree of controllability and straightforward measurement, these experimental analogies ultimately created the field of topological photonics26, enabling many exciting applications, including topologically protected lasing27,28.

Motivated by the recent discovery of skyrmions in optics29–31, and the ability of nonlinear optical processes to effectively define a spin-1/2 system32–34, we propose a method to emulate any 2D spin transport phenomenon with light, using 3D nonlinear photonic crystals (NLPCs)35–38. As a proof-of-concept, we analytically and numerically present an emulation of the topological Hall effect by engineering effective skyrmion textures for light. The effective magnetization in our proposed system is highly tunable, such that high-order skyrmion textures and domain wall fine structures, otherwise unstable in magnetic materials, may be created to probe spin transport dynamics. We also suggest methods for active, all-optical control over the effective magnetization in the NLPC, illustrating the potential of our approach to support the development of new optical and quantum optical devices inspired by spintronics. Our formalism applies to any 2D magnetization landscape and can even be extended to simulate spin transport through time-dependent magnetizations, such as melting domains39 and spin waves40. Employing the high availability of single-photon sources, our formalism may allow the quantum simulation of single-particle phenomena such as Anderson localization41 or quantum random walk42 of spin-carrying particles as well as transport phenomena with entangled spins43, which can be simulated using frequency-entangled multiphoton states.

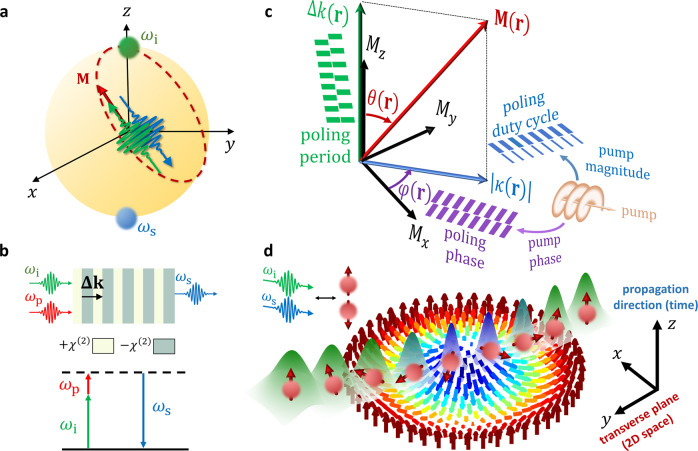

Emulating 2D spin transport necessitates a pseudospin degree of freedom, an effective magnetization field acting on the pseudospin, and a space-time along which the dynamics is probed. We define the pseudospin degree of freedom by considering a nonlinear optical process involving two interacting frequencies, which can be geometrically represented on a Bloch sphere25,32,44 (Fig. 1a–b). This degree of freedom is controlled by the inherent phase matching of the process and its complex coupling coefficient, which together define an effective magnetization field applied on the pseudospin33,45 (Fig. 1c). Considering the propagation direction as a time axis, the transverse profile of a light beam defines the wavefunction of a massive particle in two spatial dimensions (see Figs. 1d and 2a), with its dynamics dictated by the variation of the effective magnetization field in space.

Emulation of spin transport phenomena in nonlinear optics.

a Bloch sphere representation of a two-level system—here comprising the idler () and signal (

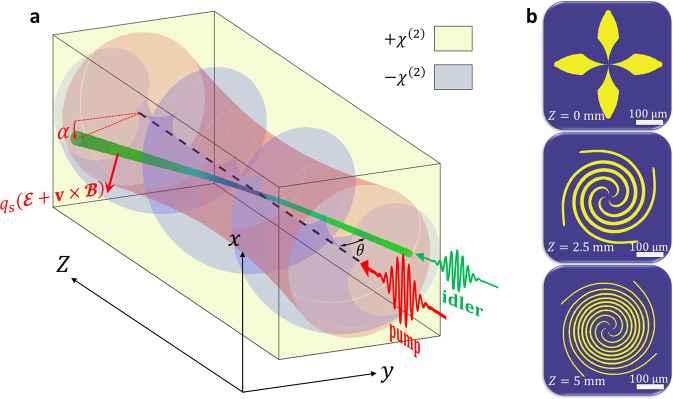

Topological Hall effect for light beams.

a A quadratic

Full control over the dynamics is achieved by engineering the nonlinearity in the material, causing the detuning from phase matching and the complex coupling strength to change in space, for a fixed pump illumination. Alternately, the complex coupling can be tailored by shaping the pump field, together with a correspondingly engineered variation in the detuning. The nonlinear process and its tunable parameters are presented in Fig. 1b-c.

In what follows, we consider the three-wave mixing process of sum-frequency generation in a quadratic nonlinear photonic crystal between an idler (Ei), signal (Es) and pump (Ep) electric fields (Fig. 1b). Assuming the pump field is strong and nondepleted, the interplay is effectively only between the idler and signal fields. In this setting, the transverse propagation of the light beam and its frequency (idler or signal) emulate the motion of a spin-1/2 particle at a certain spin state, traversing a two-dimensional magnetization texture (see Fig. 1d).

Under the long pump wavelength approximation46, the paraxial coupled wave equations for the signal and idler slowly varying envelopes are:

A local gauge transformation to the rotating frame can be applied to Eq. (1) by defining

We demonstrate the capabilities of our approach by emulating the topological Hall effect (THE), in which polarized spin currents are deflected by a topologically nontrivial magnetization texture (such as magnetic skyrmions11–13). In the adiabatic regime of the THE, the orientation of electron spin follows the local normalized magnetation direction

We implement the local gauge transformation

The synthetic magnetic field in Eqs. (4) and (5) is directly related to the geometric phase acquired during propagation of light through the crystal, and it’s magnitude is solely dependent on the real-space Berry curvature of the magnetization47. As such, only topologically nontrivial magnetization textures can induce a deflection of the beam trajectory associated with the THE (see Supplementary Material), with the so-called skyrmion number

Using our formalism, it is possible to explore the topological Hall effect occurring in otherwise thermodynamically unstable magnetization textures, such as single high-order skyrmions14. To this end, let us define a circularly-symmetric magnetization texture with a single topological defect as follows:

For the given magnetization in Eq. (6), the synthetic electric and magnetic fields are:

Though quite a specific solution, Eqs. 6,7 are still general enough such that the simulation of several meaningful magnetization textures may be achieved, through the simple task of guessing the distribution function

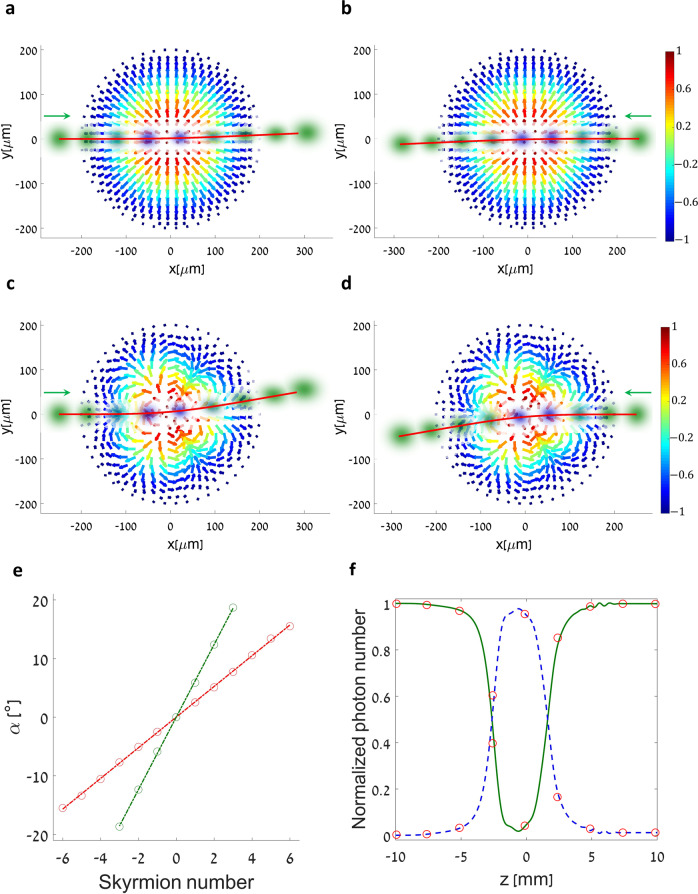

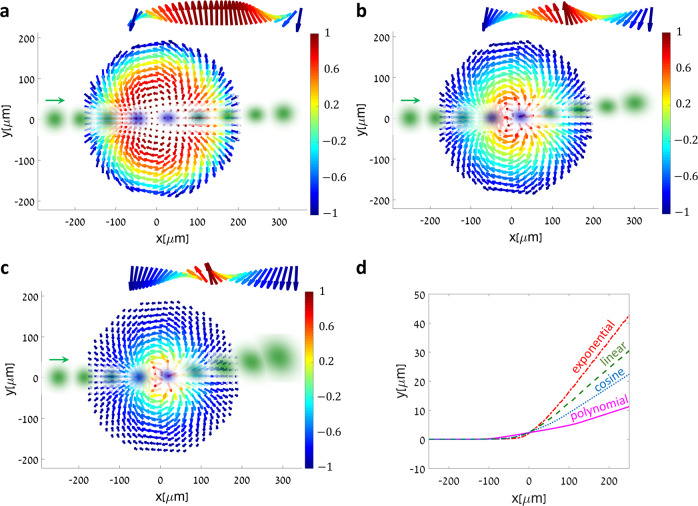

Numerical simulations of nonlinear beam propagation inside a skyrmionic NLPC, based on the split-step Fourier method (see Methods), are presented in Fig. 3. We note that in the numerical calculation we only apply standard assumptions, such as reflection-less, paraxial propagation, rather than the approximations employed for the analytical solution. Figure 3a,b shows the idler beam’s transverse dynamics as it propagates through a crystal with a skyrmion magnetization of

Simulating the topological Hall effect in skyrmionic nonlinear photonic crystals.

a, b Simulated beam shape and position in the transverse plane of the crystal, for selected depths of propagation inside the NLPC (the successive points are for

The effect becomes more pronounced for higher skyrmion numbers or smaller skyrmion radii, as illustrated in Fig. 3c–e, and in Supplementary Movies 1 and 2. Our theoretical model seems to describe the nonlinear optical system well, as evident by the predicted trajectories (red lines in Fig. 3a–d) and by the adiabatic frequency conversion during propagation (Fig. 3f), in complete analogy to the electron spin in the THE. The signal beam behaves similarly, although it is deflected to the opposite direction, as expected (see the Supplementary Material).

Interestingly, the dynamics in the THE regime can be significantly altered by the exact variation of the magnetization from one out-of-plane direction to its opposite—called the domain wall. The ability to accurately engineer 3D features of NLPCs allows us to precisely design domain walls, including the adjustment of the skyrmion winding, size and radial profile

Tailoring domain walls to engineer the topological Hall effect for light.

Simulated beam shape and position in the transverse plane of the crystal, for selected depths of propagation inside the NLPC and different domain wall distributions (

While all three configurations possess the same radius and topological invariant, they exert a different force on the light beams, resulting in different center-of-mass trajectories. The trajectories are compared in Fig. 4d, along with that found in conventional Néel-type skyrmions with cosine domain walls. Evidently, topologically equivalent magnetic textures yield different THE signatures, with the underlying mechanism being the strong singularity emerging in the synthetic magnetic field distribution (Fig. 4b, c). Interestingly, a larger and more localized Berry curvature enhances the Lorentz force, similarly to how a larger local optical angular-momentum density increases the torque applied on particles by optical vortices49, even though both effects initially stem from global topological charges.

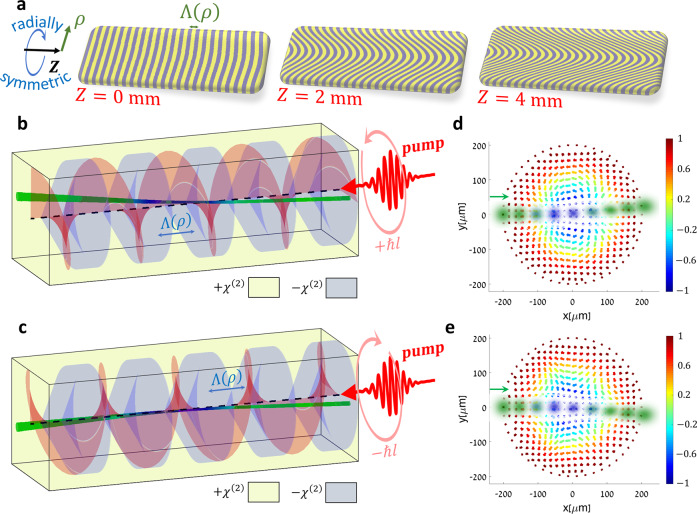

Effective magnetization textures in nonlinear optical media can also be induced directly by light, enabling diverse opportunities for all-optically-controlled devices. In the context of generating effective skyrmion magnetizations, pump fields carrying orbital angular momentum49 (OAM) can provide the required chirality25 and coupling strength variation, through their phase and intensity profiles (Fig. 1c). Thus, the NLPC design is greatly simplified, requiring only a radially varying periodicity (see Fig. 5a).

All-optical angular-momentum control of the topological Hall effect for light.

a Cross section of the three-dimensional nonlinear photonic crystal along the optical axis, showing the radial variation in the modulation period,

In this manner, the pump and crystal together induce an effective skyrmion of order

Aside from spatially modulating the pump, temporal modulation can also bring about new degrees of control. Since optical nonlinear effects relax in ultrafast time scales, modulation frequency should only be limited by the propagation time through the NLPC, allowing working rates on the order of tens of GHz for the crystal lengths considered in this work. The simplest modulation is, of course, mere intensity modulation, which turns the THE on or off. However, it is also possible to modulate the angular momentum of the pump in time, thus changing between the deflection properties of the THE.

In summary, we presented a framework to connect the fields of spintronics and nonlinear optics through the use of 3D nonlinear photonic crystals, showing how any spin transport through any 2D magnetization texture may now be emulated by light. As an example, we realized the topological Hall effect for light via effective skyrmion textures with different topologies and domain wall distribution, while showing the capability for all-optical control. Our framework can readily simulate periodic7,8,50,51 or disordered2 magnetization textures, but more importantly—emulate hard-to-implement quantum spin phenomena via quantum signal/idler light. Such phenomena include Anderson localization41 of spinors or their quantum random walks42, utilizing single-photon sources; or entangled spin transport, as in superconducting spintronics43, using multiphoton frequency-entangled states52.

Further extending our formalism may allow the simulation of scenarios where a direct experiment or numerical calculation are impractical. Such is the case when introducing Kerr nonlinearity, which could promote effective many-body interactions between pseudospins53; or cascaded nonlinear interactions, enabling the simulation of higher spin Hilbert spaces46. Even simple extensions, such as time-variance (

Novel ideas for both classical and quantum optical information processing can now benefit from decades of spintronics research, as methods and devices to control spin current may be used to direct optical flow. For example, a practical application for the all-optical modulation of a skyrmionic NLPC can be a relatively broadband32 optical router, operating in tens of GHz, for either classical optical communications or to control quantum frequency combs52—an emerging candidate for quantum information processing. Skyrmionic NLPCs could also serve as multi-level logic gates (or single-qubit gates for frequency-entangled states), where the pump OAM, or even its polarization, contain the information. Overall, the system is expected to display topological robustness for deviations in pump power, input wavelengths and poling, as was demonstrated in earlier observations of adiabatic processes in nonlinear optics32–34,57.

The experimental realization of our proposed system is fast-approaching, considering the rate of advancement in fabricating 3D NLPCs. Rather than feature resolution, which is quite sufficient35, the main challenge imposed by our system is the long crystal length

Simulations were performed using a split-step Fourier58 method, where the propagation of fields is calculated under the paraxial approximation. Idler and signal fields were initialized as Gaussian beams at

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41467-021-21250-z.

This work was supported by the Israel Science Foundation, grant no. 1415/17. A.K. and S.T. acknowledge support by the Adams Fellowship Program of the Israel Academy of Science and Humanities.

A.K. performed the numerical simulations and theoretical calculations. A.K., S.T., G.B., and A.A. conceived the project. All authors participated in analysing the results and writing the manuscript.

The data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

The code supporting the plots within this paper are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

The authors declare no competing interests.

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

6.

7.

8.

9.

10.

11.

12.

13.

14.

15.

16.

17.

18.

19.

20.

21.

22.

23.

24.

25.

26.

27.

28.

29.

30.

31.

32.

33.

34.

35.

36.

37.

38.

39.

40.

41.

42.

43.

44.

45.

46.

47.

48.

49.

50.

51.

52.

53.

54.

55.

56.

57.

58.