Whole series of nanoparticles have now been reported, but probing the competing or coexisting effects in their synthesis and growth remains challenging. Here, we report a bi-nanocluster system comprising two ultra-small, atomically precise nanoclusters, AuAg24(SR)18− and Au2Ag41(SR)26(Dppm)2+ (SR = cyclohexyl mercaptan, Dppm = bis(diphenylphosphino)-methane). The mechanism by which these two nanoclusters coexist is elucidated, and found to entail formation of the unstable AuAg24(SR)18−, followed by its partial conversion to Au2Ag41(SR)26(Dppm)2+ in the presence of di-phosphorus ligands, and an interdependent bi-nanocluster system is established, wherein the two oppositely charged nanoclusters protect each other from decomposition. AuAg24(SR)18 and Au2Ag41(SR)26(Dppm)2 are fully characterized by single crystal X-ray diffraction (SC-XRD) analysis – it is found that their co-crystallization results in single crystals comprising equimolar amounts of each. The findings highlight the interdependent relationship between two individual nanoclusters, which paves the way for new perspectives on nanocluster formation and stability.

Despite recent progress in individual nanocluster synthesis, understanding the competing or coexisting effects between particles in solution remains challenging. Here, the authors present the synthesis of a bi-nanocluster system comprising two atomically precise nanoclusters, and map out the interdependent relationship between them.

The synthesis and properties of individual nanoparticles are intriguing1–5 and have been widely studied6–15. In particular, the ligands used can profoundly affect the structure and composition of nanoparticles. For example, by using thiol ligands instead of R4N+, ultra-stable gold nanoparticles could be synthesized16–20. In addition, nanoparticle optical21,22, catalytic23–25, and magnetic26,27 properties can be controlled by modification of the structure, composition, and capping ligands of individual nanoparticles. In comparison, little is known about the interactions between nanoparticles, mainly due to their poly-disperse nature and the lack of effective in situ detection technologies. One recent breakthrough was the characterization of metal exchange behavior between two atomically precise nanoparticles28–30. Nonetheless, our understanding of the interactions between metal nanoparticles lags behind that of the individual nanoparticles themselves.

The methodology for exploring intermolecular interactions at the initial stage helps to regulate the synthesis of nanoparticles31–34. For example, the size focusing method for synthesizing atomically precise nanoparticles (nanoclusters), wherein the influence of reaction conditions (reaction temperature, growth kinetics, ligand bulkiness, etching time, ligand/metal ratio) on product nanoparticle size distribution are mapped out and then adjusted such that a specific size of product nanoparticles are obtained, is quite similar to the concept of “survival of the fittest”35,36. High-yield syntheses of molecularly pure Au38(SR)2437, Au144(SR)6038, Au64(SR)3239 have all been accomplished with this size-focusing methodology. However, the size focusing method does not necessarily result in monodisperse nanoclusters, and is more likely to afford a mixture of several different monodisperse nanoclusters. These nanoclusters can be regarded as the “fittest” in the environment in which they were formed, but although they can be separated and fully characterized, such studies generally do not inform our understanding of the relationship between them. Important open questions include: when in solution, how do nanoparticles interact with each other, leading to the coexistence of two or more nanoparticles, which are mutually beneficial? Can nanoparticles exist in the presence of each other, but not separately? The discovery of such phenomena will lead us to a deeper understanding of the formation and growth mechanism of nanoparticles, and will provide effective guideline for the design of new nanoparticles, especially metal nanoparticles with precise structure.

Herein, we report the synthesis and characterization of a bi-nanocluster system, AuAg24 and Au2Ag41, and the interdependent relationship between these two nanoclusters are mapped out. By working with precisely structured nanoclusters, we obviated the problem of poly-dispersion, which plagues the study of nanoparticles. The relatively simple nature of this bi-nanocluster system also ensures that the exterior synthetic environment is the same for each individual nanoparticle, and therefore the interactions between them are more tractable. For example, we were able to determine that the negatively charged nanocluster AuAg24(SR)18− (denoted as AuAg24) is produced first, and then some of it is converted into a positively charged nanocluster Au2Ag41(SR)26(Dppm)2+ (denoted as Au2Ag41). The two types of nanoclusters protect each other from decomposition, revealing the interdependent relationship between them. Moreover, co-crystallization of AuAg24 and Au2Ag41 resulted in crystals consisting of each of them in a molar ratio of 1:1.

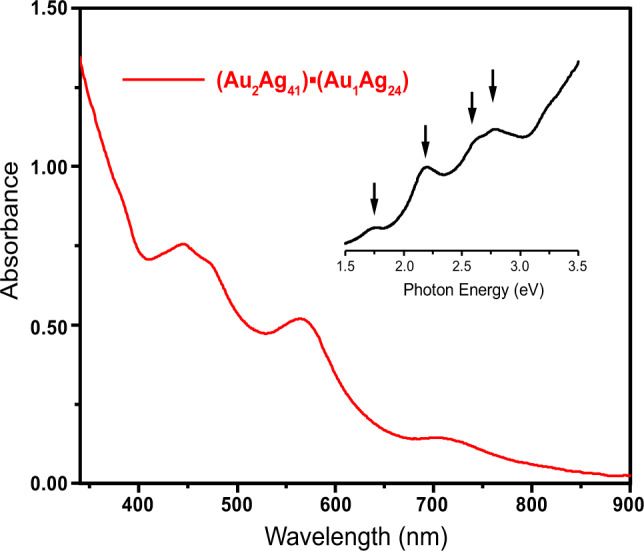

The synthesis of the title nanoclusters was performed in a one-pot method. First, the stable precursor Ag-Au-Dppm complex was synthesized as a solution in toluene. Introduction of the thiol ligand in the presence of NaBH4 resulted in the gradual formation of the nanoclusters. By adding 5 mL of n-hexane to the saturated toluene solution, single crystals could be obtained after 7 days. The resulting black single crystal was subjected to X-ray single crystal structure analysis (Supplementary Fig. 1), which revealed the co-crystallization of both AuAg24 and Au2Ag41 in a 1:1 molar ratio, and their hierarchical assembly in the triclinic space group. UV–Vis absorption spectrum of the (Au2Ag41)■(AuAg24) co-crystal showed intense peaks at ~443, 472, and 570 nm and a weaker peak at ~710 nm (Fig. 1), corresponding to excitation energies of 2.80, 2.63, 2.17, and 1.75 eV, respectively.

UV−vis absorption spectrum of the (Au2Ag41)■(AuAg24) co-crystal dissolved in CH2Cl2.

The insert shows the UV–Vis spectrum plotted on the photon energy scale.

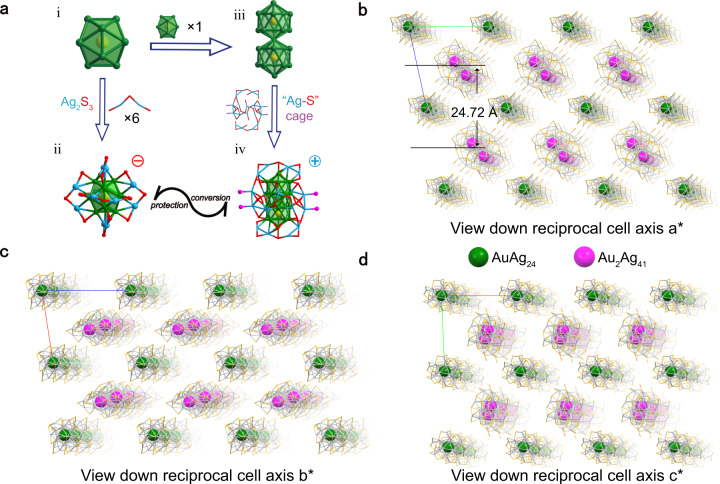

X-ray crystallographic analysis revealed that AuAg24 adopts an icosahedral M13 kernel structure, with six, one-dimensional Ag2S3 motifs surrounding 12 Ag atoms surrounding a central Au atom (Fig. 2ai-ii). The Au2Ag41 structure comprises a rod-shaped M25 kernel composed of two M13 structural units (Fig. 2aiii), wrapped by a “cage” like frame composed of the outer Ag-S-P layer (Fig. 2aiv). Detailed structural analyses of both nanoclusters are shown in Supplementary Fig. 2. The bond lengths of AuAg24 and Au2Ag41 were similar—for example, the average Aukernel-Agkernel and Agkernel-Agkernel bond lengths were 2.91 Å for Au2Ag41, slightly longer than in AuAg24 (2.88 Å). The Au2Ag41 adopted the same M25 kernel as the reported [(p-Tol3P)10Au13Ag12Br8]+40, and the average bond lengths of Au2Ag41 (2.91 Å) were almost identical with that of [(p-Tol3P)10Au13Ag12Br8]+ (2.92 Å) (Supplementary Fig. 3). AuAg24 and Au2Ag41 can be regarded as a structural unit in a stacked three-dimensional structure (Fig. 2b–d). The occupancy of each nanocluster in the unit cell was 50%, and the interlayer distance of lamellar co-crystallization was 24.72 Å (calculated from the gap between each Au plane). The molar ratio of Au2Ag41 and AuAg24 was further confirmed by 1H NMR spectroscopy (Supplementary Fig. 4); the integral area ratio of the benzene ring region (–C6H5) to the partial methylene (–CH2) region was 1:6.7, consistent with the theoretically calculated result of 1:6.6. Additionally, X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) confirmed the elemental composition of the two nanoclusters (Supplementary Figs. 5–8).

X-ray structure and packing model of (Au2Ag41)■(AuAg24) co-crystal.

a Detail analysis of AuAg24 and Au2Ag41 nanocluster. Color labels: yellow, Au; green or sky blue, Ag; red, S; fuchsia, P. All C and H atoms are omitted for clarity; b, c, and d view down reciprocal cell axis a*, b*, and c*, respectively. The interlayer distance is 24.72 Å. The packing mode of (Au2Ag41)■(AuAg24) shows that this is a lamellar co-crystallization system. All H and C atoms are omitted for clarity. To highlight, the gold atoms in AuAg24 and Au2Ag41 are highlighted in green and pink, respectively.

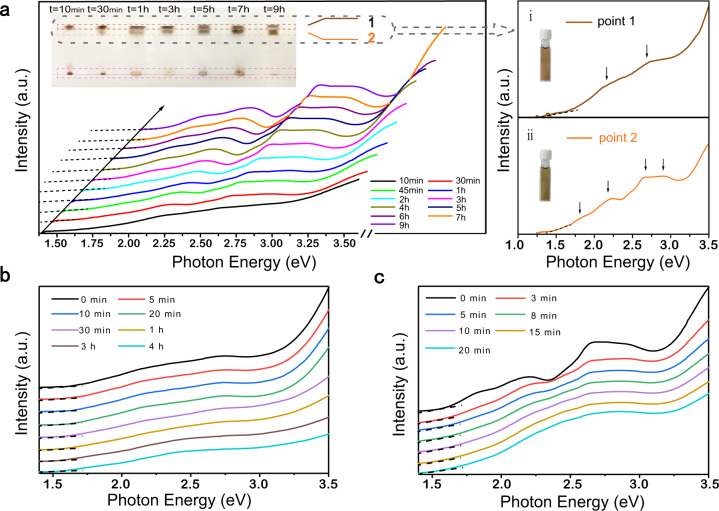

In order to elucidate the nanocluster formation process, we undertook a thin-layer chromatography study based on the time-dependent absorption peak variation in the UV–Vis spectra (Fig. 3a). “Point 1” appeared on the thin-layer chromatography plate within ten minutes of reaction initiation. As the reaction progressed, the second “point 2” gradually appeared, indicating the formation of a new component. At the same time, we obtained the UV–Vis spectra of two key points plotted on the photon energy scale (Fig. 3ai-ii). Two absorption peaks centered at ~2.17, and 2.68 eV were observed on the spectrum of “point 1”, while four absorption peaks were observed on the spectrum of “point 2” centered at ~1.79, 2.17, 2.68, and 2.90 eV, respectively.

Dynamic growth process of the bi-nanocluster.

a Time-dependent UV–Vis spectra of the reaction process from 10 min to 9 h plotted on the photon energy scale. The UV–Vis spectra of thin-layer chromatography component points dissolved in dichloromethane (ai) “point 1”, (aii) “point 2”. Insert plots: thin-layer chromatography indicates the separation of reactants at different time interval;digital photos of the dichloromethane solution of separate components. Time-dependent UV–Vis spectra showed the disappearance of totally structured features of the b “point 1”, c “point 2” at room temperature. “Points 1 and 2” represent AuAg24 and Au2Ag41, respectively.

To identify the corresponding clusters, we crystallized component 1 (“point 1”) and component 2 (“point 2”), respectively. The stabilities of components 1 and 2 were tracked by UV–Vis spectra (Fig. 3b, c). The absorption peaks centered at ~2.17, and 2.68 eV corresponding to component 1 disappeared after 4 h, whereas the peaks centered at ~1.79, 2.17, 2.68, and 2.90 eV corresponding to component 2 disappeared within 20 min. Based on this observation, both component 1 and component 2 were concluded to be unstable at room temperature. Accordingly, we added a counterion (tetraphenylphosphonium bromide) to the solution of component 1 and component 2. Single crystal X-ray diffraction (SC-XRD) results showed that component 1 was AuAg24 (Supplementary Fig. 9). The structure analysis showed it to be the negatively charged, eight-electron structure [AuAg24(SR)18]−[PPh4]+ (i.e., 1 (Au 6s1) + 24 (Ag 5s1) − 18 (SR) − (−1) (charge) = 8). Thus, Au2Ag41, which has a positive charge, acts as its counter ion in the co-crystal system.

The characteristic absorption peaks of [AuAg24(SR)18]−[PPh4]+ were centered at 570 nm and 463 nm (2.17 eV and 2.68 eV, respectively)—broader, and blue-shifted compared to published absorption data for AuAg24 (2,4-DMBT)18 (2,4-DMBT = 2,4-dimethylbenzenethiol) nanocluster— perhaps due to a ligand effect (Supplementary Fig. 10)41. Despite extensive experimentation with a variety of counterions, we were unable to stabilize component 2, the instability of which precluded its crystallization. To identify “point 2”, we resorted to comparison of its UV–Vis spectra with that of Au2Ag41, obtained by subtracting the UV–Vis spectrum of [AuAg24(SR)18]−[PPh4]+ from the UV–Vis spectrum of (Au2Ag41)■(AuAg24) at an equimolar concentration (Supplementary Fig. 11). Absorption peaks centered at ~443, 472 and 570 nm and 710 nm (corresponding to excitation energies of 2.80, 2.63, 2.17, and 1.75 eV) were observed.

Time-dependent UV–Vis spectra were recorded, to monitor the reaction (Fig. 3a). Characteristic peaks at 2.17 eV and 2.68 eV corresponding to AuAg24 appeared within the first 10 min. Later, new peaks centered at 1.79 eV and 2.90 eV appeared, the intensity of which gradually increased. These reflect formation of another component, Au2Ag41 and the formation of a stable bi-nanocluster system. 1H NMR spectra were also acquired, to further track the reaction process and confirm the relationship between the two nanoclusters. At t = 10 min of the reaction, no signals corresponding to the benzene ring region could be observed in the 1H NMR spectrum, indicating that the Au2Ag41 stabilized by both thiol and phosphine ligands was not formed. As the reaction continued, the peaks centered at 7.0–8.0 ppm gradually increased in intensity compared with the peak centered at 3.0 ppm ascribed to S-CH of cyclohexanethiol ligand (–CH), indicating the formation of Au2Ag41 (Supplementary Fig. 12).

The above results suggested that AuAg24 was produced before Au2Ag41, but did not inform the relationship between the two. We considered three possibilities: (i) AuAg24 induces the formation of Au2Ag41 in the system; (ii) AuAg24 is transformed into Au2Ag41; and (iii) the two are formed independently.

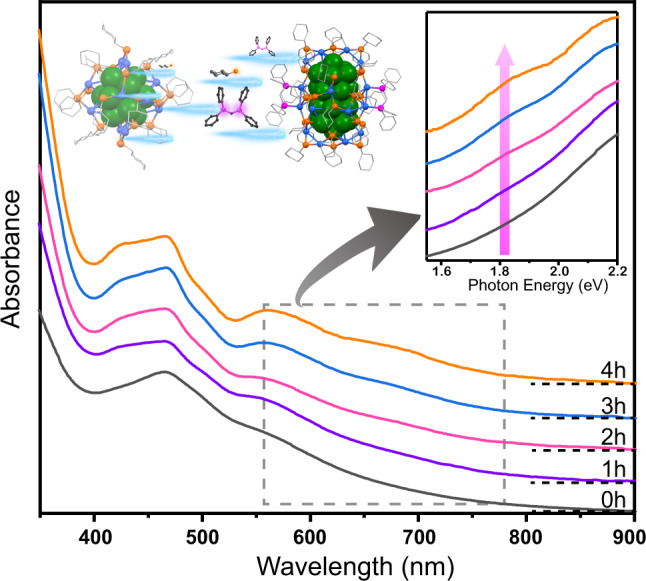

To map out the relationship between AuAg24 and Au2Ag41, we designed a conversion reaction. A sample of AuAg24 was dissolved in a mixture of dichloromethane and methanol. Then, phosphine and mercaptan ligands were added. The UV–Vis spectra of the mixture were recorded every hour from 0 min to 4 hr (Fig. 4). At 0 min, the UV–Vis spectra exhibited the characteristic absorption peaks of AuAg24 at 463 nm and 570 nm. Gradually, new absorption peaks appeared at 695 nm and 425 nm. The spectrum of final product (after 4 h) was identical to that of the bi-nanocluster. These results indicated that the partial conversion of AuAg24 to Au2Ag41 could be induced by the addition of ligands.

Time-dependent UV–Vis spectra of the nanoclusters.

Monodisperse AuAg24 is converted to (Au2Ag41)■(AuAg24) bi-nanocluster system in the presence of DPPM. Inset is the amplified photoelectron spectra, which suggest the formation of Au2Ag41 nanocluster.

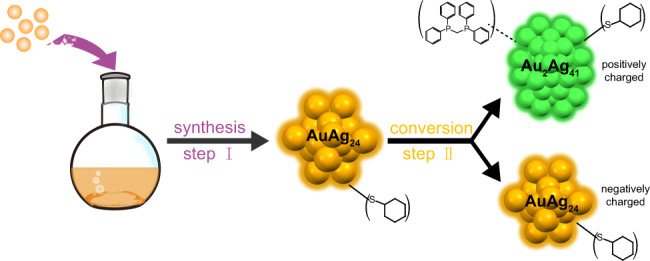

Based on the above results, a mechanism of the transformation and interaction between AuAg24 and Au2Ag41 is proposed (Fig. 5). The reaction is divided into two steps: (I) The negatively charged AuAg24 was formed at the beginning of the reaction; (II) Part of the AuAg24 nanoclusters were converted to oppositely charged Au2Ag41 due to the instability of AuAg24 in the absence of suitable counterions. Briefly, AuAg24 is susceptible to decomposition due to the absence of a suitable counter ion salt protection, causing part of it to be converted into a larger cluster with opposite valence as counter ion. These two types of nanoclusters stabilized each other to form a stable interdependent bi-nanocluster system (Supplementary Fig. 13). The behavior of the conversion from unstable nanoclusters to stable co-crystal system exhibit the synergy between different nanoclusters, which sheds light on the further preparation of new types of nanoparticles in the future.

Schematic diagram of the synthesis route for (Au2Ag41)■(AuAg24) bi-nanocluster system.

Color code: AuAg24: orange; Au2Ag41: green.

In summary, we have successfully synthesized a bi-nanocluster system and mapped out the relationship between its two constituent nanoclusters. Owing to the lack of suitable counter ion, the negatively charged AuAg24 nanocluster partially converts to the Au2Ag41 nanocluster, which bears the opposite charge. Thus, the two nanoclusters act as counter ions of each other, establishing a stable and interdependent system. The interdependent effect revealed in this work further advances the understanding of inter-nanocluster correlations.

Silver nitrate (AgNO3, 99.0%), tetrachloroauric(III) acid (HAuCI4·3H2O, 99.99%, metals basis), tetraphenylphosphonium bromide (PPh4Br, 98%), cyclohexyl mercaptan (C6H12S, 98%), bis-(diphenylphosphino)methane (Dppm, 97%), tetraphenylboron sodium (NaBH4, 99%), methanol (CH3OH, HPLC, Aldrich), acetone (CH3COCH3, Aldrich), dichloromethane (CH2Cl2, HPLC, Aldrich), methylbenzene (C6H5CH3, Aldrich), ethanol (CH3CH2OH, Aldrich), acetonitrile (C2H3N, Aldrich), hexane (C6H14, Aldrich) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. It is worth noting that the reagents used were not further purified.

AgNO3 (60 mg) and bis-(diphenylphosphino)methane (Dppm, 40 mg) were added to a 15 mL methanol solution, and the Ag-Dppm complex was formed after vigorous stirring. Gold salt (HAuCl4 • 3H2O, 4 mg) was injected into the reaction solution. After continuing to stir for 10 min, cyclohexyl mercaptan (C6H12S, 100 mg) was added, and the solution changed from white and turbid to yellow and clear. The stirring continued for 20 min until the color of the reaction no longer changed. Then, drop-wise addition of 2 mL of NaBH4 ethanol solution (25 mg) to the reaction, the color of the reaction mixture changed to yellow and then to dark. This solution was incubated for 12 h at room temperature. The solution was centrifuged to give the black crude product, which was washed by methanol, then dissolved in toluene to prepare a saturated solution. A certain amount of n-hexane was added thereto and the solution was placed in a refrigerator, and rod-shaped black crystals were obtained in about 7 days.

Typically, we obtained a yellow clear solution according to the above co-crystallization method. Immediately, the drop-wise addition of ice-cold Ethanol NaBH4 (20 mg in 2 mL Ethanol). The mixed solution was continuously stirred for 7 h in an ice bath, after which the brown compound was isolated by purification and dissolved in CH2Cl2. After that, the methanolic PPh4Br (30 mg in 2 mL methanol) was added to the solution and which was crystallized in CH2Cl2/hexane for about 14 days in a refrigerator to obtain black hexagonal crystals.

Typically, 28 mg of [AuAg24(SR)18]− [PPh4]+ nanocluster was dissolved in 15 mL of dichloromethane and methanol 1:1 mixed solution. After that, 30 μL of cyclohexyl mercaptan and 3 mg of bis-(diphenylphosphino)methane were added to the solution, and then approximately 2 mg of NaBH4 was added to the solution. Reacted for 4 h at room temperature and oxygen, the final product was collected with a yield of about 26.8%.

Ultraviolet−visible (UV−Vis) absorption spectra were recorded on an UV-6000PC spectrophotometer. X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) measurements were performed on Thermo ESCALAB 250 configured with a monochromated Al Kα (1486.8 eV) 150 W X-ray source, 0.5 mm circular spot size, a flood gun to counter charging effects, and the analysis chamber base pressure lower than 1 × 10−9 mbar; data were collected with FAT = 20 eV. Nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) analysis was performed on a Bruker Avance spectrometer operating at 400 MHz for CD2Cl2 was used as the solvent to dissolve ∼5 mg clusters; the residual solvent peak (i.e.,1H at 5.32 ppm) was used as reference. The data collection for single crystal X-ray diffraction was carried out on Stoe Stadivari diffractometer under liquid nitrogen flow at 170 K, using graphite-monochromatized Cu Kα radiation (λ = 1.54186 Å). Data reductions and absorption corrections were performed using the SAINT and SADABS programs, respectively.

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41467-021-21131-5.

We acknowledge the financial support by the NSFC (21602002 21871001 21803001 and 21901001), Anhui Provincial Natural Science Foundation (2008085QB84).

D.L. carried out experiments, analyzed the data and wrote the manuscript. S.C., X.K. and S.J. assisted the X-ray structure analysis and completed the manuscript. W.D., A.C., and Y.Z. assisted the measurements of NMR and SC-XRD. D.H., S.W., and M.Z. designed the project, analyzed the data, and revised the manuscript.

The X-ray crystallographic coordinates for structures reported in this work have been deposited at the Cambridge Crystallographic Data Center (CCDC), under deposition numbers CCDC-2007161 and 2007612. These data can be obtained free of charge from the Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre via www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/data_request/cif, which has been mentioned in the article.

The authors declare no competing interests.

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

6.

7.

8.

9.

10.

11.

12.

13.

14.

15.

16.

17.

18.

19.

20.

21.

22.

23.

24.

25.

26.

27.

28.

29.

30.

31.

32.

33.

34.

35.

36.

37.

38.

39.

40.

41.