The hallmark of superconductivity is the rigidity of the quantum-mechanical phase of electrons, responsible for superfluid behavior and Meissner effect. The strength of the phase stiffness is set by the Josephson coupling, which is strongly anisotropic in layered cuprates. So far, THz light pulses have been used to achieve non-linear control of the out-of-plane Josephson plasma mode, whose frequency lies in the THz range. However, the high-energy in-plane plasma mode has been considered insensitive to THz pumping. Here, we show that THz driving of both low-frequency and high-frequency plasma waves is possible via a general two-plasmon excitation mechanism. The anisotropy of the Josephson couplings leads to markedly different thermal effects for the out-of-plane and in-plane response, linking in both cases the emergence of non-linear photonics across Tc to the superfluid stiffness. Our results show that THz light pulses represent a preferential knob to selectively drive phase excitations in unconventional superconductors.

Josephson coupling determines the superconducting phase stiffness and sets the energy scale of plasma waves. Here, the authors show that THz light can induce two-plasmon excitations of both out-of-plane and in-plane phase modes, leading however to markedly different resonant and thermal effects due to the strong anisotropy of the Josephson couplings.

Order and rigidity are the essential ingredients of any phase transition. In a superconductor, the order is connected to the amplitude of the complex order parameter, related to the opening of a gap Δ in the single-particle excitation spectrum. The rigidity manifests instead in the quantum-mechanical phase of the electronic wave function, associated with the phase of the order parameter1. Twisting the phase is equivalent to an elastic deformation in a solid, meaning that its energetic cost is vanishing for sufficiently slow spatial variations. On the other hand, as phase fluctuations come along with charge fluctuations, long-range Coulomb forces push the energetic cost of a phase gradient to the plasma energy ωJ1,2. Although for ordinary superconductors, this energy scale is far above the THz range, in layered cuprates the existence of a weak Josephson coupling among neighboring layers3–5 provides a natural mechanism to push down to the THz range the frequency of the interlayer Josephson plasma mode (JPM), as it was proposed long ago in order to account for the soft plasma edge appearing below Tc in standard reflectivity experiments6–10. More recently, the possibility to manipulate such interlayer JPM by intense THz pulses has been experimentally proven11,12, and theoretically discussed within the context of the non-linear equation of motion for the phase variable11–16. This approach turned out to successfully capture the main features of a series of recent experiments17,18, even though a full quantum treatment of the JPM able to capture thermal effects across Tc is still lacking. On the other hand, non-linear effects induced by strong THz pulses polarized in the planes19–21 have been discussed so far only within the context of the SC amplitude (Higgs) mode or BCS response, that consists in lattice-modulated charge fluctuations in the clean limit22,23. Indeed, as their excitation energy scales in both cases as 2Δ, which range from 5 to 10 THz in cuprates, they appear in principle a better candidate than high-energy in-plane plasma waves. As it has been recently discussed by several authors24–27, even small disorder affects significantly the non-linear response by triggering in general all processes mediated by the paramagnetic electronic current, that is no more conserved. This affects the relative strength of the various processes, making ultimately the Higgs mode24–27 as well as charge/phase modes27 dominant at strong disorder. The various processes can be further distinguished by their dependence on the pump polarization, and for cuprates the Higgs response is strongly isotropic at all disorder levels, whereas the BCS one has a shallow maximum for field polarized along the diagonal of square lattice unit cell27. Nonetheless, the experiments show at least two features, which do not easily match our current expectation for both the Higgs and the BCS response: (i) a monotonic temperature dependence as T increases20,21, with a persistence above Tc21 and (ii) a finite and doping-dependent polarization dependence with a minimum for field polarized along the diagonal19.

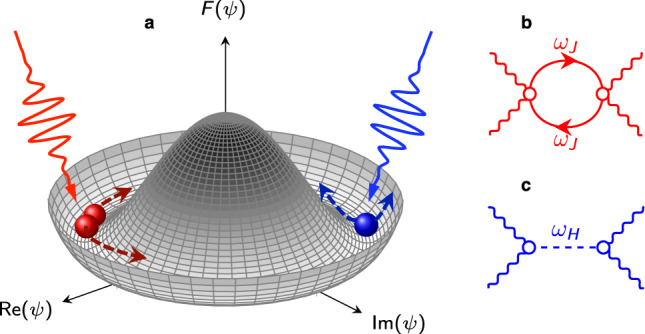

Here, we provide a complete theoretical description of the JPM contribution to the non-linear response of layered cuprate superconductors, focusing both on third-harmonic generation (THG) and pump-probe protocols for pump fields applied both out-of-plane and in plane. We first address the out-of-plane response and we show that the basic mechanism behind non-linear photonic of Josephson plasma waves is intrinsically different from the one of the Higgs mode, see Fig. 1. By pursuing the analogy with lattice vibrations in a solid, the Higgs mode is like a Raman-active optical phonon mode. It has a finite frequency at zero momentum, and its symmetry allows for a finite quadratic coupling to light22–33. The phase mode behaves instead like an acoustic phonon mode, pushed to the plasma energy by Coulomb interaction, carrying out a finite momentum at nonzero frequency. As such, zero-momentum light pulses can only excite simultaneously two JPMs with opposite momenta. As a consequence the excitation of out-of-plane JPMs strongly depends on the thermal probability to populate excited states and on the matching condition between the pump frequency and the JPM frequency scale, resulting in a non-monotonic dependence of the THG in temperature. We then turn our attention on the in-plane response. In this case, as the frequency scale of the in-plane JPMs is much larger than Tc and of the THz pump frequency, the THG monotonically scales in temperature with the in-plane superfluid stiffness. In addition, in contrast to the Higgs mode22,26,27, for a light pulse polarized in the planes the signal coming from JPMs is in general anisotropic, as the momenta carried out by the two plasmons can be along different crystallographic axes. All these features not only contribute to the understanding of the existing experimental measurements17–21, but they also offer a perspective to design future experiments aimed at selectively tune non-linear photonic of Josephson plasma waves in layered cuprates.

Non-linear excitation of phase and Higgs modes.

a Schematic view of the mexican-hat potential for the free energy F(ψ), with ψ the complex order parameter of a superconductor below Tc. A phase-gradient excitation corresponds to a shift along the minima, whereas a Higgs excitation moves the system away from the minimum. An intense light pulse with almost zero momentum can excite simultaneously two plasma waves with frequency ωJ and opposite momenta (in red) or a single Higgs fluctuation with frequency ωH = 2Δ (in blue). b–c Feynman-diagrams representation of the b plasma waves or c Higgs contribution to the non-linear optical response. Here wavy lines represent the e.m. field, solid/dashed lines the plasmon/Higgs field, respectively.

To elucidate the basic mechanism behind the two-plasmon non-linear response we first discuss the case of the out-of-plane JPM. We take a layered model with planes stacked along z. In the SC state the Josephson coupling J⊥ of the SC phase ϕn between neighboring planes sets an effective XY model:

To compute the third-order contribution in Eq. (3) we need to derive the effective action S(4) for the gauge field up to terms of order

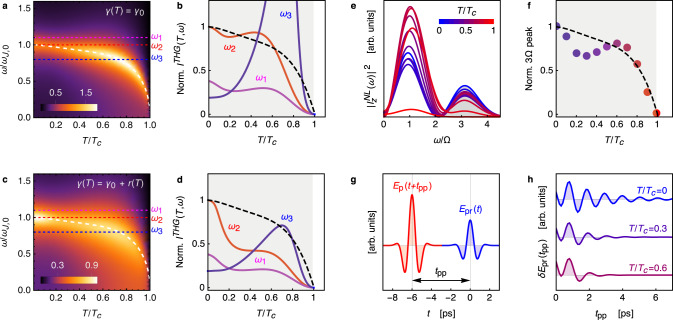

Once derived the two-plasmon contribution to the non-linear optical kernel, let us compute the THG for a field polarized in the out-of-plane direction. The temperature dependence of the JPM non-linear kernel (7) and the corresponding THG (8) for a narrow-band pulse are shown in Fig. 2a–d for different values of the pump frequency ω. Here we modeled J⊥(T) and the corresponding ωJ(T) according to the out-of-plane superfluid stiffness measured in ref. 18. In general, the THG for the out-of-plane response is not monotonic, as one has to face with three different temperature effects in K(2ω): (i) the suppression of J⊥(T) and ωJ(T) with temperature; (ii) the increase of

Non-linear excitation of out-of-plane JPM.

a–d Narrow-band pulse. Temperature and frequency dependence of the non-linear kernel (7) ∣K(2ω, T)∣, normalized to its T = 0 value for the pumping frequency ω = ωJ,0, for constant a and temperature-varying c damping γ. The dashed line denotes ωJ(T)/ωJ,0. b, d show the corresponding ITHG(ωi, T) for three values ωi of the pump frequency, normalized to its T = 0 value for the pumping frequency ω2 = ωJ,0. The dashed line represents J⊥(T)/J⊥(0). e–h Broadband pulse. e Spectrum of the non-linear current

The THG for a field polarized along z has been measured so far only by means of a broadband pump18. To make a closer connection with this experimental setup we then simulated (see Methods) the THG for a short (τ = 0.85 ps) pump pulse Ep(t) with central frequency Ω/2π = 0.45 THz, as shown in Fig. 2g. The frequency spectrum of the resulting non-linear current

In the broadband case, the nature of the non-linear kernel can also be probed via a typical pump-probe experimental setup, schematically summarized in Fig. 2g. As it has been theoretically described in ref. 23,37 for the transmission geometry, the oscillations of the differential probe field with and without the pump δEpr(tpp) as a function of the pump-probe time delay can be directly linked to the resonant non-linear optical kernel. In the case of the out-of-plane response (7) one then obtains (see Methods):

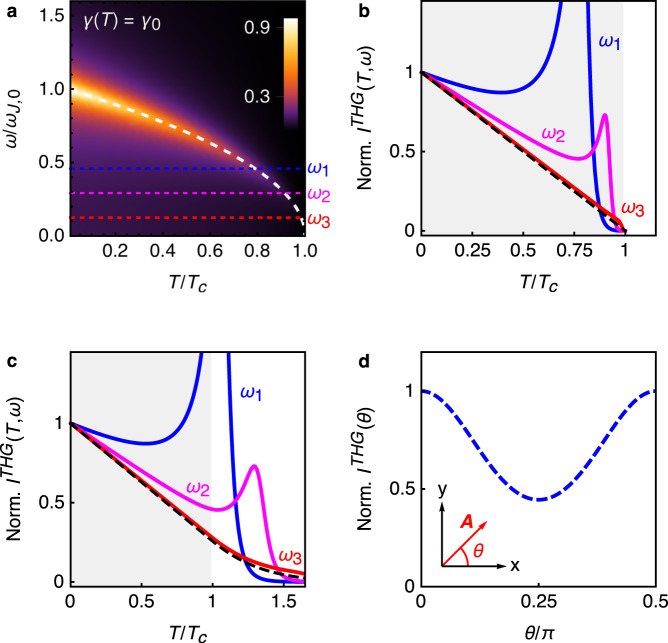

Let us consider now the effects of a strong THz pulse polarized within the plane. In this case, we can generalize the model (4) by taking into account both the two-dimensional nature of the phase fluctuations in the plane and the anisotropy of penetration depth measured experimentally in cuprates3–5, where λc ≃ 10−100λab depending on the material and the doping, and λab ≃ 2000 Å, so that

Non-linear excitation of in-plane JPM.

a Temperature and frequency dependence of the non-linear kernel ∣K∥(2ω, T)∣, normalized to its T = 0 value for the pumping frequency ω = ωJ,0, for constant damping γ. The dashed line denotes

Our work establishes the theoretical framework to manipulate and detect JPMs in layered cuprates across the superconducting phase transition. The basic underlying mechanism relies on the excitation of two plasma waves with opposite momenta by an intense field. For the out-of-plane response, we support the well-established approach based on non-linear sine-Gordon equations11,14,15,17,18, adding a complete description of thermal effects and highlighting the possibility to tune the resonant excitation of JPMs by changing the temperature. For the in-plane response, we suggest the possible relevance of JPMs to explain several puzzling aspects emerging in recent measurements in different families of cuprates19–21. Although for the out-of-plane response the strong incoherent quasiparticle transport automatically suppresses all electronic mechanisms, leaving the JPM as the only plausible candidate to explain non-linear effects, for the in-plane case an open question remains a quantitative estimate of the signal coming from the JPMs, as compared with the one owing to the Higgs or to BCS quasiparticle excitations. Indeed, as the recent theoretical work on disordered superconducting models demonstrated24–27, even weak disorder becomes crucial to estimate the relative strength of the various possible processes, and to establish the polarization dependence of the response27. Nonetheless, as we have shown, even in the absence of a quantitative estimate of the hierarchy of the various effects the temperature and polarization dependence of the non-linear response can be used to discriminate different contributions. In our modeling, the large value of the in-plane plasma frequency comes along with a large value for the in-plane stiffness J∥, which controls the non-linear coupling of the JPM to the e.m. field. This suggests that especially near optimal doping, where J∥ attains its maximum value, a two-plasmon THG signal can be comparable to other effects. An interesting additional question is a possibility that a finite supercurrent triggered by a very strong THz field, as the one recently discussed within the context of second-harmonic generation in conventional superconductors31,41, could also allow for single-plasmon excitations processes. From this perspective, the theoretical and experimental investigation of non-linear phenomena induced by intense THz pulses represents a privileged knob to probe the relative strength of pairing and phase degrees of freedom in unconventional superconducting cuprates.

The derivation of the quantum action for the phase degrees of freedom can be done following a rather standard approach, see, e.g., refs. 1,34,35 and references therein. The basic formalism relies on the quantum action representation of a microscopic superconducting model in the presence of long-range Coulomb interactions. The collective variables corresponding to the amplitude, phase, and density degrees of freedom are introduced via an Hubbard–Stratonovich decoupling of the interacting superconducting and Coulomb term. This allows one to integrate out explicitly the fermionic degrees of freedom in order to obtain a quantum action in the collective variables only, whose coefficients are expressed in terms of fermionic susceptibilities, computed on the SC ground state. The result for the Gaussian phase-only action in the isotropic three-dimensional case reads:

The current Iα in the α = (x, y, z) direction is defined as usual as the functional derivative with respect to Aα of the action SA. Thus, to compute the third-order contribution to Iz in Eq. (3) we need to expand the e.m. action up to terms of order

For what concerns the in-plane JPM, we follow the same procedure starting from the interaction term of Eq. (11). In this case, the quartic action has a structure similar to Eq. (18) provided that K⊥ is replaced by a two-component tensor:

For a narrow-band multicycle pulse, one can assume a monochromatic incident field, and the THG is simply related to the non-linear optical kernel via Eq. (8). However, for a broadband pulse with central frequency Ω, the THG is more generally associated with the 3Ω component in the non-linear current22,23. We then computed the non-linear current from Eq. (19) by using a realistic pump spectrum A(ω), obtained by Fourier transform of

In a pump-probe experiment designed to excite the out-of-plane JPM, both the pump and probe fields are polarized along z, i.e., Ez = Epr(t) + Ep(t). Here, we will refer for simplicity to the transmission configuration, as discussed in ref. 23,37, where one measures the variation δEpr(t) of the transmitted probe field with and without the pump, so that terms not explicitly depending on the pump field cancel out. This allows one to express it as

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41467-021-21041-6.

We acknowledge useful discussions with C. Castellani, A. Cavalleri, and D. Nicoletti. We thank the authors of ref. 18 for providing us with the experimental data used to estimate J⊥(T) in Fig. 2. This work has been supported by the Italian MAECI under the Italian-India collaborative project SUPERTOP-PGR04879, by the Italian MIUR project PRIN 2017 No. 2017Z8TS5B, by Regione Lazio (L.R. 13/08) under project SIMAP and by Sapienza University under project Ateneo 2019 (Grant No. RM11916B56802AFE).

F.G. and M.U. contributed equally to this work. L.B. conceived the project and supervised its development. F.G., M.U. and L.B. performed the analytical calculations. F.G. and M.U. performed the numerical simulations. L.B. wrote the manuscript with inputs from all the authors.

All data generated during this study are included in this published article (and its supplementary information files).

The authors declare no competing interests.

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

6.

7.

8.

9.

10.

11.

12.

13.

14.

15.

16.

17.

18.

19.

20.

21.

22.

23.

24.

25.

26.

27.

28.

29.

30.

31.

32.

33.

34.

35.

36.

37.

38.

39.

40.

41.