- Altmetric

Though the concept of Berry force was proposed thirty years ago, little is known about the practical consequences of this force as far as chemical dynamics are concerned. Here, we report that when molecular dynamics pass near a conical intersection, a massive Berry force can appear as a result of even a small amount of spin-orbit coupling (<10−3 eV), and this Berry force can in turn dramatically change pathway selection. In particular, for a simple radical reaction with two outgoing reaction channels, an exact quantum scattering solution in two dimensions shows that the presence of a significant Berry force can sometimes lead to spin selectivity as large as 100%. Thus, this article opens the door for organic chemists to start designing spintronic devices that use nuclear motion and conical intersections (combined with standard spin-orbit coupling) in order to achieve spin selection. Vice versa, for physical chemists, this article also emphasizes that future semiclassical simulations of intersystem crossing (which have heretofore ignored Berry force) should be corrected to account for the spin polarization that inevitably arises when dynamics pass near conical intersections.

Spin polarization is at the basis of quantum information and underlies some natural processes, but many aspects still need to be explored. Here, the authors, by quantum mechanical computations, show that even a weak spin-orbit coupling near a conical intersection can induce large spin selection, with consequences for spin manipulation in photochemical or electrochemical reactions.

Introduction

Electronic spin is one of the most fundamental observables in quantum mechanics, and manipulating spin (so-called “spintronics”) is an enormous and exciting field of research today1–7. Even though the energy associated with flipping a single spin is incredibly small (6 μeV in the presence of a 0.1 T magnetic field), non-trivial spin manipulation can be achieved today through various techniques that center around the coupling between electronic motion and spin dynamics. Today, there are many physicists studying how giant and tunnel magnetoresistance8,9, spin–orbit torques10–12, spin–transfer torques13–17, and spin Hall effects18–20 can produce spin polarization either in the presence of external magnetic fields or carefully chosen solid-state materials with some degree of ferromagnetism or both. Interestingly, however, recent chiral-induced spin selectivity (CISS) experiments by Naaman, Waldeck, and co-workers21–23 have demonstrated that unusually large electronic spin polarization can also arise when current is passed through chiral molecules without ferromagnetic materials or magnetic fields (and despite very small spin–orbit coupling (SOC) matrix elements). It would appear that, as a community, we still have a great deal to learn about the subtle means by which non-trivial spin effects emerge in practice.

One means of achieving spin polarization that has not yet been fully explored theoretically (and one that appears to have large experimental consequences) is the coupling of molecular nuclear motion to electronic spin in the presence of SOC (but without any magnetic fields). In the simplest approximation, for a radical reaction with an odd number of electrons, one can consider a two-state Hamiltonian in a diabatic basis of the form (where Tnu is the nuclear kinetic operator, r, θ are polar coordinates of nuclear position),

For the Hamiltonian in Eq. (1), the underlying physical mechanism behind any possible spin polarization here is the Lorentz-like force (FB) arising from the Berry curvature of the electronic surfaces26–28. This force is ignored by most dynamical simulation tools in chemistry29 and historically Berry forces have been presumed small in chemistry30; nevertheless, FB can be incredibly important (as shown below). Let

Now if one wishes to map a realistic ab initio Hamiltonian to the reduced Hamiltonian in Eq. (1), one can roughly estimate the parameter W (which represents the gradient of the coupling phase) from the ratio of the SOC strength to diabatic coupling strength. In other words, for a two-state Hamiltonian H = H0 + HSOC, where H0 is the real-valued, standard electronic Hamiltonian and HSOC is purely imaginary, the phase of the diabatic coupling

However, the situation is more subtle around a conical intersection (CI)31–33, which is known to be essential for mediating a vast array of photochemical relaxation processes. On the one hand, the canonical thinking heretofore has always been that the geometric Berry force around a CI (as caused exclusively by a complex-valued Hamiltonian) should not lead to drastically different nuclear dynamics—a real-valued Hamiltonian should contain the bulk of nuclear dynamics through a CI. For example, in his seminal paper on geometric magnetism, Berry argued: “These classical effects will however be weak, since the monopole strength is

In this work, we follow the present train of thought and investigate coupled nuclear–spin dynamics around an “avoided” complex-valued CI. More precisely, our target system is a real-valued spin-free Hamiltonian (H0) for which we find a CI; however, we add to this Hamiltonian a second, constant complex-valued Hamiltonian (HSOC), which formally eliminates or moves away the CI38–40. We find that in this case the Berry magnetic force can yield a truly enormous effect, with spin-separation efficiencies close to 100% at certain energies. Furthermore, because the degree of spin polarization depends on the ratio between the SOC and the non-SOC diabatic coupling, and the diabatic coupling vanishes at a CI, we find that a huge amount of spin polarization can occur even with a very weak SOC.

Results

Model Hamiltonian

In this article, we will work with the electronic Hamiltonian plotted in Fig. 1. Mathematically, for the case of spin up electrons, we assume there are two electronic states (both with the same spin) and two nuclear degrees of freedom, for which there is one incoming channel and two outgoing channels:

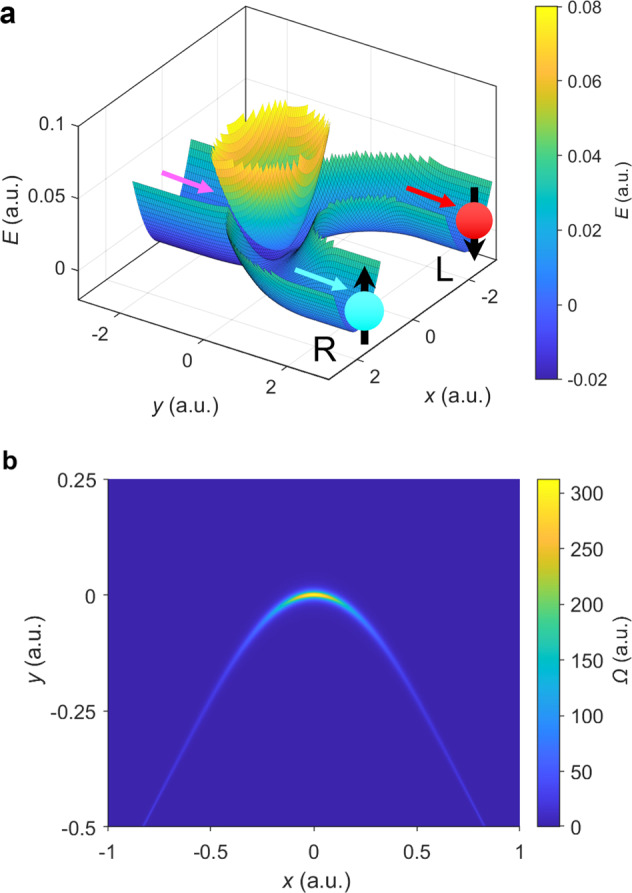

The potential surfaces and Berry curvature for the model Hamiltonian (Eq. (7)).

a The adiabatic potential surfaces. On the ground state, the incoming channel (marked by the magenta arrow) is in the direction y → −∞ at x = 0, the two outgoing channels (L and R, marked by the red and blue arrow according to their spin preferences) are in the direction y → +∞ at x = ±r0. Nuclear wave packets associated with the spin-up electronic states prefer channel R while nuclear wave packets associated with spin-down electronic states prefer channel L. The perturbed CI is at x = 0, y = 0. b The Berry curvature Ω of the ground adiabatic surface around the intersection point. Here the model parameters (defined in Eq. (8)) are: A = 0.02, ω = 0.01, M = 103, ϵ1 = 2.5, ϵ2 = 2.5, r0 = 2, μ = 10−3, λ = 2 × 10−4 (all in atomic units). Note the avoided CI becomes a true CI when λ = 0 (Supplementary Fig. 1).

Below, we will imagine a situation where a nuclear wavepacket approaches the avoided crossing from the y →−∞ channel and then can emerge in one of the two y → +∞ channels that are displaced in the x-direction: The left (L) channel flows along x = r0; the right (R) channel flows along x = −r0. See Fig. 1. For the Hamiltonian in Eq. (7), we will show that the wavepacket chooses one channel predominantly over the other. Physically, this choice of channel means that a nuclear wavepacket with one spin (say spin up) will emerge into one channel. By symmetry, incoming wave packets with other spin will have the exact same preference for the other channel (i.e., the channel at x = −r0). These spin-dependent nuclear wave packets are plotted heuristically in Fig. 1a.

In Fig. 1b, we plot the Berry curvature of the ground adiabatic state

Transmission probabilities

We have run scattering calculations for the Hamiltonian in Eq. (7) using the exact procedure outlined in refs. 25,41. We calculate the transmission rates TL and TR for each channel in Fig. 1. The nuclei enter asymptotically from the y → −∞ channel (with spin up and nuclear motion bound to the ground state in the x direction); the nuclei can emerge in either the L or R channels. The total incoming energy E is defined by

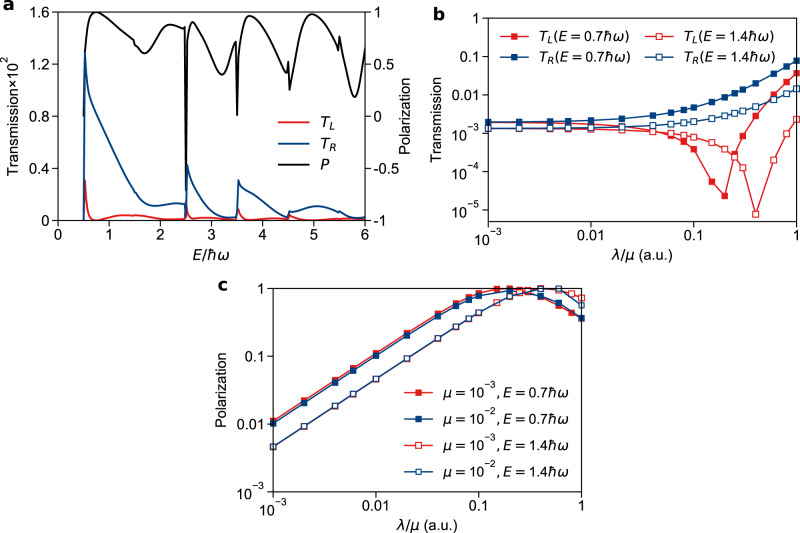

In Fig. 2a, we plot the individual transmission rates T for the two channels TL and TR as well as the spin selectivity P ≡ (TR − TL)/(TR + TL), both as functions of the total incoming energy E. Here one sees a huge preference for the right channel over almost all of the entire energy range. At certain incoming energies such as E = 0.7

Transmission rates (TL and TR) and spin selectivity P = (TR − TL)/(TR + TL) for dynamics along the Hamiltonian in Eq. (7).

a

TL, TR, and P as functions of the incoming energy. Note that the selectivity is very large, almost always >50% and often close to 100%. Here the model parameters (defined in Eq. (8)) are λ = 10−3 and μ = 2 × 10−4. b

TL and TR as function of λ/μ with two fixed incoming energies E = 0.7

Next, in Fig. 2b, we plot TL and TR as a function of the reduced parameter λ/μ with a fixed μ = 10−3 at two incoming energies E = 0.7

Finally, in Fig. 2c, we plot the polarization P as a function of λ/μ with μ = 10−3 and 10−2, again with two incoming energies (E = 0.7

Discussion

It is now fully appreciated that a huge number of photochemical processes in solution are indeed mediated through CIs; even though the seams of CIs arise with co-dimension 2 in configuration space, the effects of the enormous derivative couplings around CIs fill up configuration space and act as a funnel to bridge different electronic surfaces. In the present article, we have shown that, whenever SOC is present, these CIs can also potentially lead to something not well appreciated: non-trivial spin polarization as mediated by a Berry force.

Looking forward, this article opens up many avenues for future experiments and theoretical investigation. First, there are many examples of photoinduced spin chemistry in the literature, for which time-dependent electron paramagnetic resonance spectroscopy can measure unpaired electrons interacting with their environment and for which there is no simple molecular explanation42. Furthermore, there are also hosts of magnetic field effects within organic photochemistry24,43–45 that have not yet been fully understood, including the hot topic nowadays of avian magnetoreception44,46–48. Overall, within the broad areas of organic photochemistry and spin chemistry, the impact of Berry forces has not yet been explored, which represents a huge opportunity for theoretical discovery.

Second, recent studies by Naaman et al. have shown that, even without photoexcitation or magnetic field effects, spin-dependent conductivity can arise when current is passed through chiral molecules, an effect known as CISS21–23,49,50. To date, theory has been unable to explain why the CISS effect is as large as it is, given how small the SOC matrix elements are22,50–55. The present article must make one wonder whether CIs can be found within the manifold of conducting electronic states, such that a Berry force can help explain the large magnitude of spin selection. To our knowledge, no one has (as of yet) looked for an isotope effect within the context of CISS experiments, but such an isotope effect would indeed confirm such a hypothesis. We note that recent studies have shown that electron transfer in organic molecules such as DNA and proteins are largely incoherent56–59, which is consistent with the possibility that nuclear motion (and the associated Berry force) may well lead to spin selectivity. Moreover, the CISS effect has already been shown to lead to changes in overpotential for water splitting and novel magnetic field effects60, suggesting that, if we can indeed use Berry force to produce spin-selected molecular fragments, there may be a host of future applications, including new spin-dependent catalytic mechanisms, exotic stable molecular spin devices, and efficient electrochemical metal–ion separation protocols.

Now, the experiments above represent interesting potential applications in spin chemistry and physics. At the same time, however, we must emphasize that, in order for practical progress to be made with quantitative experimental predictions, two theoretical questions will need to be addressed. First, in the present article, we have used exact quantum mechanics to calculated scattering rates. These calculations are very expensive and do not always offer a simple explanation of the physics we observe. More generally, for large systems, we will require new semiclassical tools (that treat nuclei classically) that are both inexpensive and that can offer intuitive pictures of electronic and spin relaxation. Developing such tools (e.g., extending Tully’s surface hopping algorithm29,61 to the case of complex-valued Hamiltonians) will be essential if we are to study systems with many electronic states and many nuclear degrees of freedom (ideally ab initio systems).

Second, the question of exactly when and how Berry force and/or magnetic fields lead to observable effects in the condensed phase remains a general problem for spin chemistry. On the one hand, from a classical perspective, a magnetic field does not affect the equilibrium solution to a Fokker–Planck equation, and the magnitude of molecular SOC or hyperfine interactions are orders of magnitude smaller than the thermal energy kBT in the room temperature43,50. Thus one might be led to believe that magnetic field effects (and thus Berry force) must vanish with enough friction. On the other hand, however, the Berry force near a complex-valued avoided CI can be very large. Furthermore, for a molecule that is exposed to an out-of-equilibrium environment (e.g., a current running through the molecule), the fluctuation-dissipation theorem does not hold and there is no reason to expect that external friction will eliminate the influence of Berry force and/or spin polarization. For example, a molecule near a metal surface will feel a Berry force in the form of an asymmetric electronic friction tensor when there is an electric current62–67. Note that Naaman and other researchers have shown that the CISS effect increases with increasing voltage, such that the molecular dynamics is far from equilibrium23,68–71. Obviously, extrapolating from the present simulations to the condensed phase, and calculating the effect of a Berry-force induced spin polarization in the presence of friction, will be a crucial next step forward. Clearly, several key obstacles remain if we are to ever merge theoretical chemistry with the field of spintronics.

In summary, we have demonstrated that dynamics in the vicinity of a complex-valued avoided CI can lead to extremely strong spin selectivity for reaction pathways (close to 100%); this selectivity can hold even when the SOC matrix elements are weak. This article suggests that, in the future, simulations of nonadiabatic dynamics through CIs may find enormous spin polarization effects if SOC is included and Berry force is taken into account. Furthermore, in practice, this article also highlights the possibility that, with a proper understanding of photochemical mechanisms, organic chemists may be able to synthesize molecules that ensure spin selection, thus taking a very different approach toward the development of spintronics.

Source data

Unsupported media format: /dataresources/secured/content-1765837733711-1164ceb6-a165-4219-b87d-b8a08456062e/assets/41467_2020_20831_MOESM2_ESM.zip

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41467-020-20831-8.

Acknowledgements

This work was funded by the Center for Sustainable Separation of Metals, an NSF Center for Chemical Innovation (CCI) Grant CHE-1925708. J.E.S. thanks David Reichman and Abe Nitzan for very helpful conversations.

Author contributions

J.E.S. conceived the idea and supervised the project; Y.W. performed the simulation and data analysis. Both the authors contributed to writing the manuscript.

Data availability

The authors declare that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the paper and the supplementary information files. Source data are provided with this paper.

Code availability

The code used for scattering calculation is available at https://github.com/subotnikgroup/scatter272.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

References

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

6.

7.

8.

9.

10.

11.

12.

13.

14.

15.

16.

17.

18.

19.

20.

21.

22.

23.

24.

25.

26.

27.

28.

29.

30.

31.

32.

33.

34.

35.

36.

37.

38.

39.

40.

41.

42.

43.

44.

45.

46.

47.

48.

49.

50.

51.

52.

53.

54.

55.

56.

57.

58.

59.

60.

61.

62.

63.

64.

65.

66.

67.

68.

69.

70.

71.

72.

Electronic spin separation induced by nuclear motion near conical intersections

Electronic spin separation induced by nuclear motion near conical intersections