- Altmetric

Clarifying the relation between the whole and its parts is crucial for many problems in science. In quantum mechanics, this question manifests itself in the quantum marginal problem, which asks whether there is a global pure quantum state for some given marginals. This problem arises in many contexts, ranging from quantum chemistry to entanglement theory and quantum error correcting codes. In this paper, we prove a correspondence of the marginal problem to the separability problem. Based on this, we describe a sequence of semidefinite programs which can decide whether some given marginals are compatible with some pure global quantum state. As an application, we prove that the existence of multiparticle absolutely maximally entangled states for a given dimension is equivalent to the separability of an explicitly given two-party quantum state. Finally, we show that the existence of quantum codes with given parameters can also be interpreted as a marginal problem, hence, our complete hierarchy can also be used.

The quantum marginal problem interrogates the existence of a global pure quantum state with some given marginals. Here, the authors reformulate it as an optimisation problem, and specifically as the existence of a two-party separable state with additional semidefinite constraints.

Introduction

For a given multiparticle quantum state it is straightforward to compute its marginals or reduced density matrices on some subsets of the particles. The reverse question, whether a given set of marginals is compatible with a global pure state, is, however, not easy to decide. Still, it is at the heart of many problems in quantum physics. Already in the early days, it was a key motivation for Schrödinger to study entanglement1, and it was recognized as a central problem in quantum chemistry2. There, often additional constraints play a role, e.g., if one considers fermionic systems. Then, the anti-symmetry leads to additional constraints on the marginals, generalizing the Pauli principle3,4. A variation of the marginal problem is the question of whether or not the marginals determine the global state uniquely or not5–7. This is relevant in condensed matter physics, where one may ask whether a state is the unique ground state of a local Hamiltonian8,9. Many other cases, such as marginal problems for Gaussian and symmetric states10,11 and applications in quantum correlation12, quantum causality13, and interacting quantum many-body systems14,15 have been studied.

With the emergence of quantum information processing, various specifications of the marginal problem moved into the center of attention. In entanglement theory, a pure two-particle state is maximally entangled, if the one-particle marginals are maximally mixed. Furthermore, absolutely maximally entangled (AME) states are multiparticle states that are maximally entangled for any bipartition. This makes them valuable ingredients for quantum information protocols16,17, but it turns out that AME states do not exist for arbitrary dimensions, as not always global states with the desired mixed marginals can be found18–21. In fact, also states obeying weaker conditions, where a smaller number of marginals should be maximally mixed, are of fundamental interest, but in general it is open when such states exist22–24. More generally, the construction of quantum error-correcting codes, which constitute fundamental building blocks in the design of quantum computer architectures25–27, essentially amounts to the identification of subspaces of the total Hilbert space, where all states in this space obey certain marginal constraints. This establishes a connection to the AME problem, which consequently was announced to be one of the central problems in quantum information theory28.

In this paper, we rewrite the marginal problem as an optimization problem over separable states. Here and in the following, the term marginal problem usually refers to the pure state marginal problem in quantum mechanics. This rewriting allows us to transform the nonconvex and thus intractable purity constraint into a complete hierarchy of conditions for a set of marginals to be compatible with a global pure state. Each step is given by a semidefinite program (SDP), the conditions become stronger with each level, and a set of marginals comes from a global state, if and only if all steps are passed. There are at least two advantages of writing the marginal problem as an SDP hierarchy: First, the symmetry in the physical problem can be directly incorporated to drastically simplify the optimization (or feasibility) problem. Second, many known efficient and reliable algorithms are known for solving SDPs29, which is in stark contrast to nonconvex optimization. To show the effectiveness of our method, we consider the existence problem of AME states. By employing the symmetry, we show that an AME state for a given number of particles and dimension exists, if and only if a specific two-party quantum state is separable. In fact, this allows us to reproduce nearly all previous results on the AME problem30 with only few lines of calculation. Finally, we show that our approach can also be extended to study the existence problem of quantum codes.

Results

Connecting the marginal problem with the separability problem

The formal definition of the marginal problem is the following: Consider an n-particle Hilbert space

The main idea of our method is to consider, for a given set of marginals, the compatible states and their extensions to two copies. Then, we can formulate the purity constraint using an SDP. First, let us introduce some notation. Let

Two-party extension for the marginal problem.

In the marginal problem, one aims to characterize the pure states

To impose the purity constraint, we take advantage of the well-known relation32

What remains to be done is the characterization of the set

Theorem 1

There exists a pure quantum state

Proof On the one hand, if there exists a pure state

On the other hand, if the solution of Eq. (7) is equal to one, then the separability constraint and Eq. (6) imply that ΦAB must be of the form33

Before proceeding further, we would like to add a few remarks. First, in Theorem 1 the constraint in Eq. (9) can be replaced by a stronger condition

Second, if one finds that

Third, the separability condition in the optimization Eq. (8) is usually not easy to characterize, hence relaxations of the problem need to be considered. The first candidate is the positive partial transpose (PPT) criterion34,35, which is an SDP relaxation of the optimization in Eq. (7). The PPT relaxation provides a pretty good approximation when the local dimension and the number of parties are small. In the following, inspired by the symmetric extension criterion36, we propose a multi-party extension method and obtain a complete hierarchy for the marginal problem.

The hierarchy for the marginal problem

In order to generalize Theorem 1, we first need to extend

Complete hierarchy for the marginal problem.

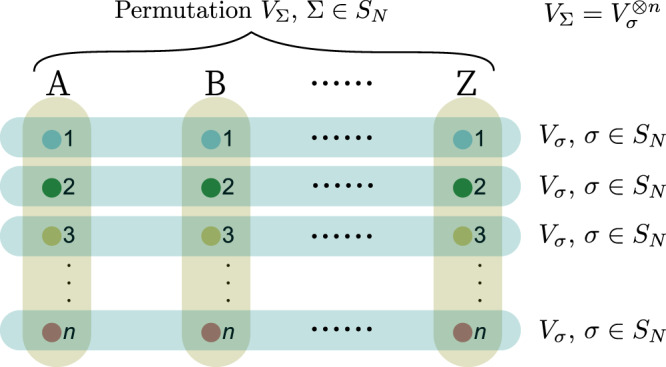

In order to formulate the hierarchy for the marginal problem, one extends the two copies in Fig. 1 to an arbitrary number of copies N. If the marginal problem has a solution

Suppose that there exists a pure state

Theorem 2

There exists a pure quantum state

The proof of Theorem 2 is shown in the “Methods” section. Notably, we can add any criterion of full separability, e.g., the PPT criterion for all bipartitions, as extra constraints to the feasibility problem. Then, Theorem 2 still provides a complete hierarchy for the quantum marginal problem. In addition, the quantum marginal problems of practical interest are usually highly symmetric. These symmetries can be utilized to largely simplify the problems in Theorems 1 and 2. Indeed, taking advantage of symmetries is usually necessary for practical applications, because the general quantum marginal problem is QMA-complete37,38. Notably, even for non-overlapping marginals, despite recent progress in refs. 39–41, it is still an open problem whether there exists a polynomial-time algorithm. In the following, we illustrate how symmetry can drastically simplify quantum marginal problems with the existence problem of AME states.

Absolutely maximally entangled states

We first recall the definition of AME states. An n-qudit state

To resolve this size issue, we investigate the symmetries that can be used to simplify the feasibility problem. Let

In the following, we will show that the symmetries of the set of AME states (if they exist for given n and d) are restrictive enough to leave only a single unique candidate for ΦAB, for which separability needs to be checked. The set of AME(n, d) is invariant under local unitaries and permutations on the n particles, so by Theorem 1 (or by direct verification) the following two classes of unitaries satisfy Eq. (29),

First, let us view VAB and ΦAB as V12…n and Φ12…n, where i labels the subsystems AiBi. Hereafter, without ambiguity, we will omit the subscripts of

Inserting this ansatz in Eqs. (27) and (28) one can show by brute force calculation that the xi are uniquely determined and given by

Theorem 3 An AME(n, d) state exists if and only if the operator ΦAB defined by Eqs. (35) and (36) is a separable state w.r.t. the bipartition (A∣B) = (A1A2…An∣B1B2…Bn).

To check the separability of ΦAB, we first consider the positivity condition and the PPT condition. It is easy to see that ΦAB can be written as

The explicit form of pi and qi and the proof of the conditions in Eqs. (40) and (41) are shown in Supplementary Note 2. The positivity and PPT conditions can already rule out the existence of many AME states. Actually, they can reproduce all the known nonexistence results30 except AME(7, 2)20. To get a higher-order approximation, we provide a general framework for performing the symmetric extension in Supplementary Notes 3 and 4.

As the open problem of the existence of AME(4, 6) is of particular interest in the quantum information community28,43, we explicitly express it as the following corollary.

Corollary 1 An AME(4, 6) state exists if and only if the quantum state

At the moment, we are unable to decide separability of these states; in Supplementary Note 5 we provide a short discussion of this problem.

Quantum codes

As another application, we show that our method can also be used to analyze the existence of quantum error-correcting codes. For simplicity, we only consider pure quantum codes44 in the text; see “Methods” for the general case. Our starting point is the fact that pure quantum codes are closely related to m-uniform states18. More precisely, an ((n, K, m+1))d pure code exists if and only if there exists a K-dimensional subspace

Lemma 1

A quantum ((n, K, m+1))d

pure code exists if and only if there exists a quantum state

Proof We first show the necessity part. Suppose that a ((n, K, m+1))d code with corresponding subspace

To prove the sufficiency part, let

Thus, Theorem 1 gives a necessary and sufficient condition for the existence of ((n, K, m+1))d pure codes.

Proposition 1

A quantum ((n, K, m+1))d

pure code exists if and only if there exists ΦAB

in

Furthermore, the multi-party extension and symmetrization techniques that we developed for AME states can be easily adapted to the quantum error-correcting codes. For instance, the PPT relaxation can be written as a linear program and the symmetric extensions can be written as SDPs. An important difference is that the symmetrized ΦAB for quantum error-correcting codes is no longer uniquely determined by the marginals in general. Finally, we would like to mention that Lemma 5 is of independent interest on its own. For example, Eq. (45) implies that

Discussion

We have shown that the marginal problem for multiparticle quantum systems is closely related to the problem of entanglement and separability for two-party systems. More precisely, we have shown that the existence of a pure multiparticle state with given marginals can be reformulated as the existence of a two-party separable state with additional semidefinite constraints. This allows for further refinements: First, one may use the multi-party extension technique to develop a complete hierarchy for the quantum marginal problem. Second, one can use symmetries of the original marginal problem, to restrict the search of the two-party separable state further. For the AME problem, this allows us to determine a unique candidate for the state, and it remains to check its separability properties. Finally, the approach can be extended to characterize the existence of quantum codes.

Our work provides new insights into several subfields of quantum information theory. First, it may provide a significant step towards solving the problem of the existence of the AME(4, 6) state or quantum orthogonal Latin squares, a problem which has been highlighted as an outstanding problem in quantum information theory28. Second, there are already a variety of results on the separability problem, and in the future, these can be used to study marginal problems in various situations. Finally, it would be interesting to extend our work to other versions of the marginal problem, e.g., in fermionic systems or with a relaxed version of the purity constraint. We believe that our approach can also lead to progress in these cases.

Methods

Proof of Theorem 2. To prove Theorem 2, we take advantage of the following lemma, which can be viewed as a special case of the quantum de Finetti theorem46.

Lemma 2

Let

ρN

be an

N-party quantum state in the symmetric subspace

The necessity part of Theorem 2 is obvious. Hence, we only need to prove the sufficiency part, i.e., that the existence of an N-party quantum state ΦAB⋯Z for arbitrary N implies the existence of

General quantum codes

In general, a quantum ((n, K, m+1))d code exists if and only if there exists a K-dimensional subspace

Lemma 3

A quantum ((n, K, m+1))d

code exists if and only if there exists a quantum state

If the marginals ρI are given like in the case of pure codes, the problem reduces to a marginal problem. However, to ensure the existence of ((n, K, m+1))d codes, an arbitrary set of marginals is sufficient. This makes the problem no longer a marginal problem, however, we can circumvent this issue by observing that Eq. (57) is equivalent to

Proposition 2

A quantum ((n, K, m+1))d

code exists if and only if there exists ΦAB

in

By noticing that the set of ((n, K, m+1))d (pure or general) codes, or rather, the set of states

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41467-020-20799-5.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Felix Huber and Géza Tóth for discussions. This work was supported by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG, German Research Foundation - 447948357), the ERC (Consolidator Grant 683107/TempoQ), and the House of Young Talents Siegen. N.W. acknowledges support by the QuantERA grant QuICHE and the German ministry of education and research (BMBF grant no. 16KIS1119K).

Author contributions

X.-D.Y., T.S., N.W., H.C.N., and O.G. participated in deriving the results and writing the manuscript. O.G. supervised the project.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Data availability

Data sharing not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

Code availability

The codes used for this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

References

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

6.

7.

8.

9.

10.

11.

12.

13.

14.

15.

16.

17.

18.

19.

20.

21.

22.

23.

24.

25.

26.

27.

28.

29.

30.

31.

32.

33.

34.

35.

36.

37.

38.

39.

40.

41.

42.

43.

44.

45.

46.

47.

A complete hierarchy for the pure state marginal problem in quantum mechanics

A complete hierarchy for the pure state marginal problem in quantum mechanics