Reversibility of an electrode reaction is important for energy-efficient rechargeable batteries with a long battery life. Additional oxygen-redox reactions have become an intensive area of research to achieve a larger specific capacity of the positive electrode materials. However, most oxygen-redox electrodes exhibit a large voltage hysteresis >0.5 V upon charge/discharge, and hence possess unacceptably poor energy efficiency. The hysteresis is thought to originate from the formation of peroxide-like O22− dimers during the oxygen-redox reaction. Therefore, avoiding O-O dimer formation is an essential challenge to overcome. Here, we focus on Na2-xMn3O7, which we recently identified to exhibit a large reversible oxygen-redox capacity with an extremely small polarization of 0.04 V. Using spectroscopic and magnetic measurements, the existence of stable O−• was identified in Na2-xMn3O7. Computations reveal that O−• is thermodynamically favorable over the peroxide-like O22− dimer as a result of hole stabilization through a (σ + π) multiorbital Mn-O bond.

Majority of oxygen-redox electrodes exhibit a large voltage hysteresis but its origin is not fully understood. Here, the authors use combined RIXS and magnetic measurements to provide insights into the origin of the typically large voltage hysteresis observed upon oxygen redox.

Lithium-ion batteries are presently the de facto standard power sources for portable electronic devices and electric vehicles due to their high energy density and efficiency relying on intercalation chemistry, whereby a host electrode material reversibly accommodates lithium ions without a large structural change1–3. As the reaction Gibbs energy for the oxidation of an electrode material (|ΔrGox | ) is almost the same as that for the reduction (|ΔrGred | ), the charge/discharge processes of an intercalation electrode usually proceed with minimal energy loss. For any electrochemical energy storage devices, the use of reversible redox chemistry (|ΔrGox | ≈ |ΔrGred | ) is a primary requisite to maximize their energy efficiency.

Lithium-rich transition metal oxides (Li1+xM1-xO2, M = transition metal) are promising large-capacity positive electrode materials for lithium-ion batteries, as they exhibit accumulative redox reactions of M and O4–6. However, the voltage profile of Li1+xM1-xO2 typically includes a large hysteresis during initial and subsequent charge/discharge cycles, in part due to structural changes such as cation migration and surface cation densification7–9. Although the oxygen-redox-active sodium counterpart NaxMyO2 can partly suppress cation migration due to the larger ionic size difference between Na and M, a large voltage hysteresis is still observed in many cases10–18. As energy efficiency is crucial for energy storage devices, the voltage hysteresis of oxygen-redox electrodes should be addressed for their practical application.

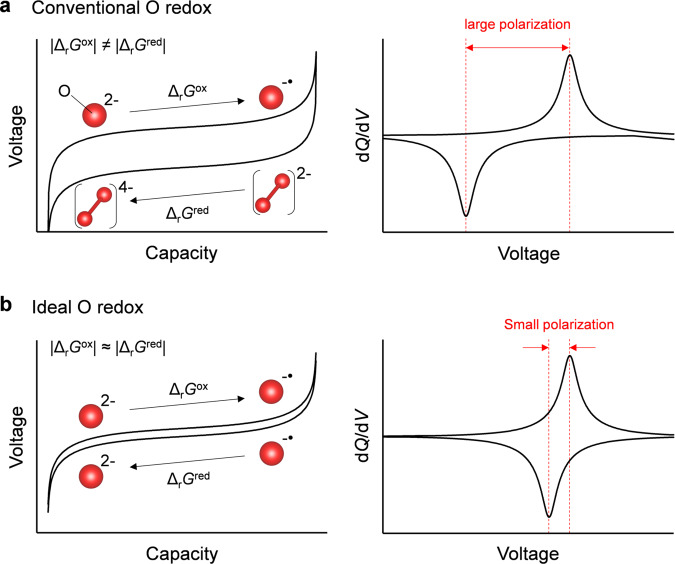

Although the mechanism of the oxygen-redox reaction is still under debate, it is generally accepted that nonbonding oxygen 2p states free from M-O σ hybridization are localized just below the Fermi level to contribute to oxygen oxidation19–24; however, the chemical state of oxidized oxygen remains controversial. Considering the large voltage hysteresis (|ΔrGox | ≠ |ΔrGred | ), oxidized oxide ions (O−•) are believed to form stable peroxide-like O22− dimers upon charging. Upon subsequent discharging, the O22− dimer may be initially reduced to O24−, and then decomposed to O2− (Fig. 1a)16,25–29. Besides such thermodynamic hysteresis, there is an overlapping kinetic hysteresis arising from concentration overpotential when transition-metal migration and/or surface cation densification occur in parallel, making elucidation of the overall mechanisms difficult 7–9.

Polarizing and nonpolarizing oxygen-redox positive electrodes.

Schematic illustration of charge/discharge curves and dQ/dV plots (Q: specific capacity, V: reaction voltage) for a conventional oxygen redox with large polarization (O2−/O22−), and b ideal oxygen redox with small polarization (O2−/O−•). The red sphere denotes oxygen atom.

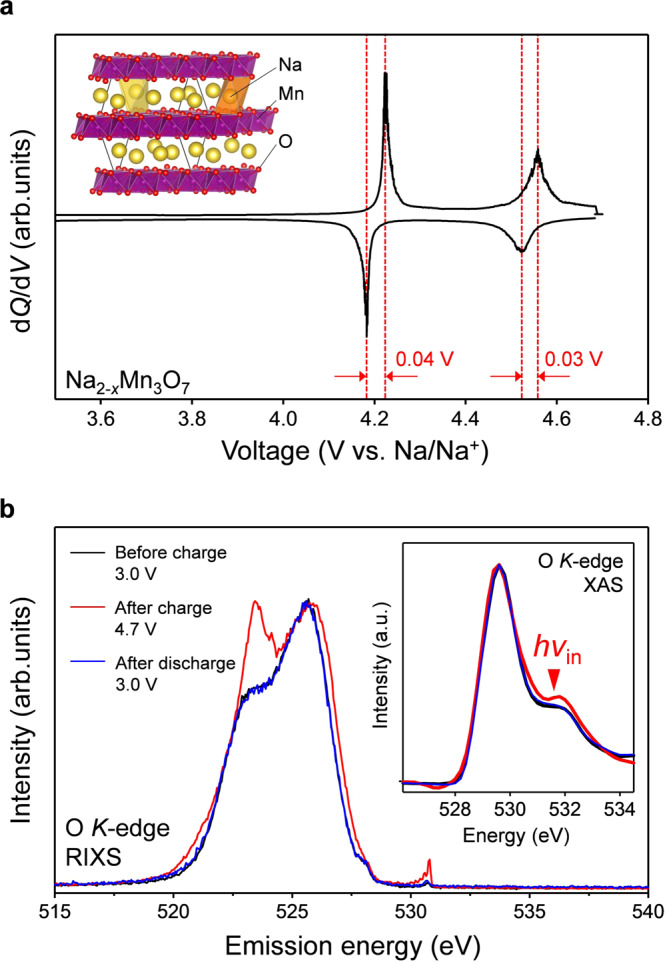

In striking contrast to the large voltage hysteresis (>0.5 V) observed for most oxygen-redox electrodes, Na2-xMn3O7 was very recently discovered to exhibit a highly reversible oxygen-redox capacity with negligible voltage hysteresis (<0.04 V)30–33. Hence, Na2Mn3O7 can serve as an excellent counterpart (Fig. 1b, |ΔrGox | ≈ |ΔrGred | ) for insights into the origin of the typically large voltage hysteresis observed upon oxygen redox. Na2Mn3O7 possesses a layered structure comprising alternatively stacked Na and Mn slabs (Fig. 2a inset) with characteristic Mn vacancies (□) in in-plane ordering34. Density functional theory (DFT) calculations suggested that a localized oxygen 2p orbital along the Na-O-□ axis contributes to the oxygen-redox capacity31. While the nonpolarizing oxygen-redox capacity strongly implicates charge compensation from the reversible redox couple of O2−/O−• (Fig. 1b) without any contribution from O22−, no experimental evidence for the stable existence of O−• has been identified for any oxygen-redox electrodes. Also important is unveiling how O−• is stabilized in Na2-xMn3O7.

Non-polarizing oxygen-redox positive electrode Na2Mn3O7.

a dQ/dV plot (Q: specific capacity, V: reaction voltage) of Na2-xMn3O7 at C/20 during the second charge/discharge cycle between 3.0–4.7 V vs. Na/Na+. Inset shows the crystal structure of Na2Mn3O7 (yellow sphere: sodium, purple sphere: manganese, red sphere: oxygen). b O K-edge resonant inelastic X-ray scattering (RIXS) spectra for Na2-xMn3O7 before the second charge (3.0 V, black line), after the second charge (4.7 V, red line), and after the second discharge (3.0 V, blue line) with excitation energy of 531.5 eV. Inset shows corresponding O K-edge X-ray absorption spectra (XAS).

Herein, evidences confirming the existence of O−• as the dominant state in the highly reversible oxygen redox of Na2-xMn3O7 are provided. After magnetic susceptibility measurements to confirm the major contribution of O−•, the thermodynamically favorable presence of O−• over peroxide-like O22− in Na2-xMn3O7 is substantiated via DFT calculations, and finally, the hole stabilization mechanism of O−• is examined.

Na2Mn3O7 was synthesized from a solid-state reaction following a reported procedure30,31. The powder X-ray diffraction pattern for the resulting compound (Supplementary Fig. 1) is indexed to triclinic P

O K-edge X-ray absorption spectra (Fig. 2b inset) show the emergence of a new absorption peak at 531.5 eV after the charge process, which corresponds to the excitation of an O 1 s core electron to an O 2p hole, as commonly observed for other oxygen-redox electrodes35–38. To monitor the detailed valence partial density of states (pDOS) of oxygen, resonant inelastic X-ray scattering (RIXS) spectra were measured using an incident photon of 531.5 eV. The emergence of a new emission peak at 523 eV in the RIXS spectrum for charged Na2-xMn3O7 is typical for charged oxygen-redox electrodes5,24,28,39,40. Although O−• formation is implicated by the small voltage hysteresis in the charge/discharge processes (Fig. 2a), the new inelastic scattering can be explained by either (1) energy loss from a π(Mn-O) → π*(Mn-O) transition (O−• formation), or (2) energy loss from a σ(O-O) → σ*(O-O) transition (peroxide-like O22− formation)40. While observation of the new RIXS peak at 523 eV confirms the occurrence of the oxygen-redox reaction itself in Na2-xMn3O7, but this evidence alone does not definitely identify the reaction mechanism, or the chemical state of the oxidized oxygen species.

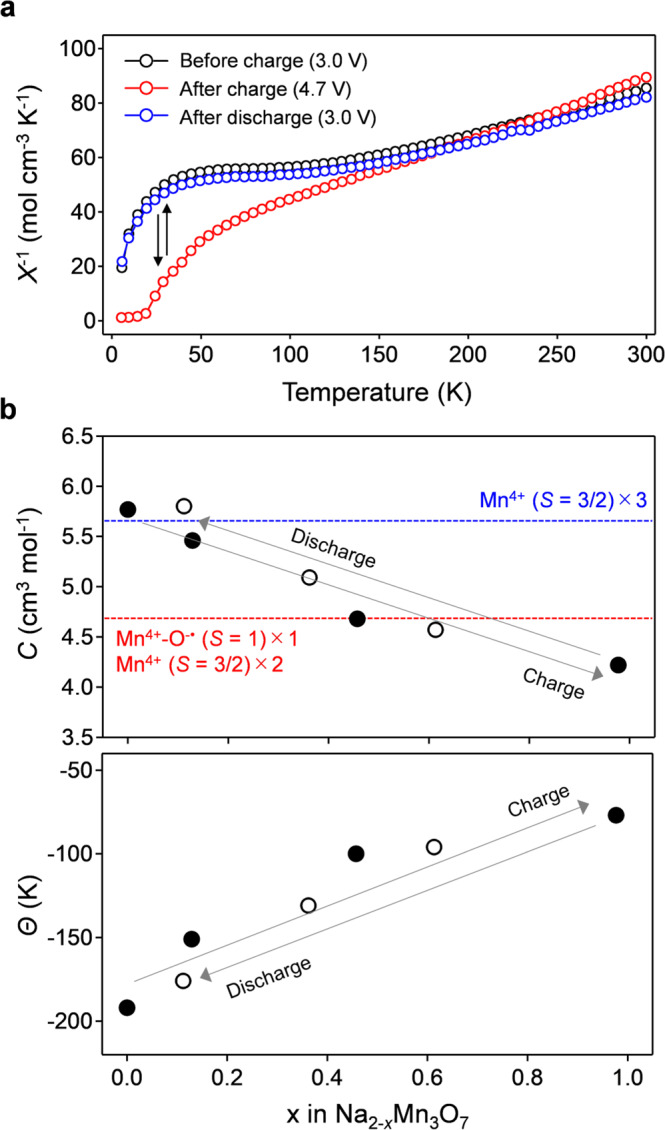

To identify the oxidized species, we measured the magnetic susceptibility

Magnetic elucidation of the existence of O− in Na2-xMn3O7.

a The inverse of a magnetic susceptibility (χ) as a function of temperature, and b Curie constant (C) and Weiss temperature (Θ) for Na2-xMn3O7 during the second cycle. Filled and empty circles correspond to data points for the charge and discharge processes, respectively.

The value of

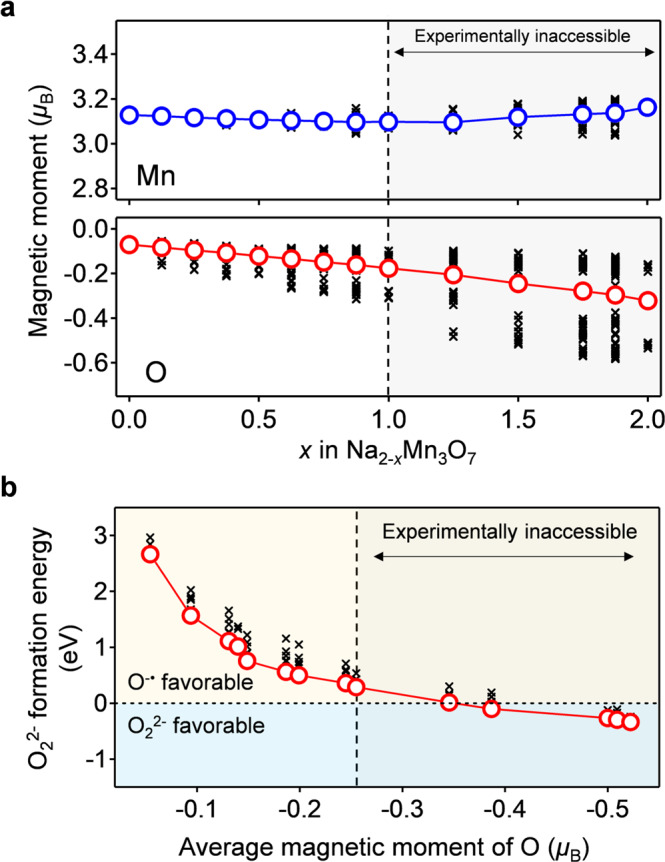

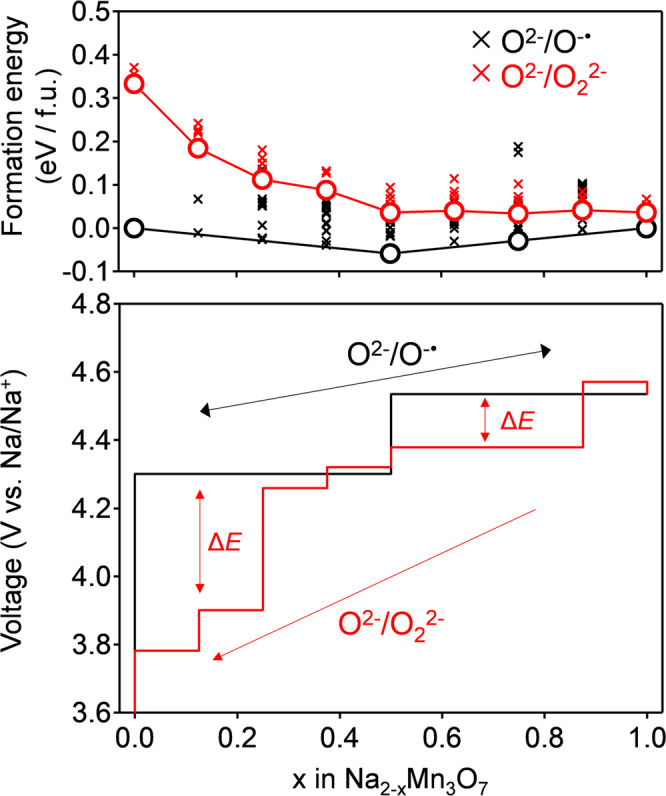

Why does Na2-xMn3O7 specifically exhibit the reversible oxygen-redox reaction of O2−/O−•? To answer this question, we compared the thermodynamic stability of O−• and peroxide-like O22− in Na2-xMn3O7 using DFT calculations. Figure 4a shows the calculated magnetic moments of Mn and O in optimized structures without peroxide-like O22− (Supplementary Fig. 4a). For the experimentally accessible desodiation range (0 ≤ x ≤ 1 in Na2-xMn3O7), a magnetic moment gradually emerges on the O atoms upon desodiation, which indicates O−• formation. The slight decrease in the average magnetic moment of Mn is explained by the initiation of metal-to-ligand charge transfer (π back-donation) from the formation of a ligand hole (O−•)40. The calculated voltage profile under the O−• formation model (Fig. 5 and Supplementary Fig. 5) accurately reproduces the experimentally observed voltage plateaus (4.30 and 4.53 V), further supporting O−• formation in Na2-xMn3O7.

Theoretical derivation of stable existence of O−• in Na2-xMn3O7.

a Calculated magnetic moments of Mn and O as a function of x in Na2-xMn3O7, and b calculated formation energy of peroxide-like O22− as a function of the average magnetic moment (i.e., degree of oxidation) of O in Na2-xMn3O7. For the plots of the magnetic moments, black crosses are a magnetic moment of each atom, while blue and red circles are average magnetic moments. For the plot of the formation energy, black crosses represent the formation energy of various O-O pairs, while red circles represent the lowest value at each desodiated state. Gray shaded area is experimentally inaccessible due to too high desodiation potential (see Supplementary Fig. S5).

Predicted voltage hysteresis of Na2-xMn3O7 with hypothetical peroxide-like O22− dimers.

DFT calculated convex hull and voltage profile of Na2-xMn3O7 with O−• and with O22−. The formation energies of both pristine structures and peroxide phases were calculated relative to pristine Na2Mn3O7 and NaMn3O7 phases. Black and red crosses in the convex hull are formation energies of Na2-xMn3O7 with O−• and with O22−, respectively. Black and red circles are the lowest states at various desodiated states. The black solid line of the voltage profile represents the charge/discharge curves without O22− formation, while the red solid line represents the discharge curve for hypothetical Na2-xMn3O7 with O22−.

The formation energy of peroxide-like O22− in Na2-xMn3O7 was calculated for various O-O pairs, where calculated O-O bond lengths for the lowest energy structures are in the peroxide O22− range of 1.46-1.47 Å (Supplementary Fig. 4b)47. The average magnetic moment of the O-O dimers is small (-0.094(6) μB), also suggesting the formation of peroxide-like O22− rather than superoxide-like O2− when O-O dimerization occurs. The formation energy of O22− (Fig. 4b) was calculated as the difference between the total energies of Na2-xMn3O7 with O−• and with O22− as a function of the average magnetic moment of O (i.e., the degree of O oxidation). During the experimentally accessible charge process (0 ≤ x ≤ 1 in Na2-xMn3O7), the formation energy of O22− is positive relative to that of O−•, indicating that Na2-xMn3O7 with O−• is thermodynamically favorable compared to Na2-xMn3O7 with O22−. Presumably, a hole on O−• in Na2-xMn3O7 is stabilized through a (σ + π) multiorbital Mn-O bond40, as demonstrated using a crystal orbital overlap populations (COOP) analysis in our previous works31. Note that, in parallel with a localized feature, the oxygen hole has an itinerant feature through the (σ + π) multiorbital interaction. Indeed, the experimentally observed value of C for Na1Mn3O7 (4.22 cm3 K mol-1) is slightly lower than that calculated for a localized model (4.75 cm3 K mol−1) (Fig. 3b).

Figure 4a also indicates that further oxygen oxidation leads to negative O22− formation energy (O22− favorable): the oxygen oxidation lowers the energy level of O 2p well below that of Mn t2g, which renders Mn-O interaction weak48. In the balance of competing stabilization mechanisms via (σ + π) multiorbital Mn-O bond versus peroxide O-O bond, the adequate oxygen-redox capacity (approximately 70 mAh/g, Supplementary Fig. 3) keeps the (σ + π) multiorbital stabilization dominant, making O−• stable in Na2-xMn3O7. It should also be emphasized that the calculated voltage profile for the sodiation of Na2-xMn3O7 with O22− shows a voltage hysteresis of 0.3–0.5 V relative to the charge process of Na2-xMn3O7 with O−• (Fig. 5), which clearly contradicts the experimental observations. O22− formation is therefore inhibited in Na2-xMn3O7, leading to an O2−/O−• based reversible and nonpolarizing oxygen-redox capacity. Excessive oxidation of oxygen (e.g., x ≥ 1 in Na2-xMn3O7), which drives O−• to dimerization, is an absolute taboo for a nonpolarizing oxygen-redox capacity48,49. Based on this criterion, the oxygen-redox reaction should be employed as an auxiliary charge-compensation mechanism under a prudent control rather than as a main charge-compensation mechanism.

As recently demonstrated using O2-type layered oxides23,50, the suppression of cation migration is essential to mitigate the degradation of oxygen-redox cathodes. However, although cation migration should accelerate O-O dimer formation16,20,51, the suppression of cation migration alone is not enough to explain nonpolarizing oxygen-redox reaction. For example, P2- and P3-Na2/3MgxMn1-xO2 deliver large extra oxygen-redox capacities greater than 100 mAh/g with large polarization, where O-O dimers could be formed without cation migration15,52. This scenario, O-O dimerization without cation migration, is indeed predicted by the DFT calculations (Fig. 4). Correlation between cation migration and O-O dimerization involving thermodynamic and kinetic issues, and its influence on the voltage hysteresis is debatable, calling for further studies.

In summary, multiple experimental and computational pieces of evidence were identified to confirm the O2−/O−• based reversible and nonpolarizing oxygen-redox reaction in Na2-xMn3O7. The competitive O22− formation is energetically unfavorable when low-concentration O−• (i.e., < Na1Mn3(O−•)1O6) is highly stabilized by a (σ + π) multiorbital Mn-O bond. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first experimental confirmation of the existence of O−• in an oxygen-redox electrode. Considering the importance of energy efficiency, the exclusive use of O2−/O−• as a redox couple is a primary requisite to utilize oxygen-redox electrodes in practical battery applications, identifying a crucial criterion for the development of efficient nonpolarizing oxygen-redox electrodes.

Na2Mn3O7 was synthesized by sintering the stoichiometric mixture of NaNO3 and MnCO3 at 600 °C under O2 flow for 4 h30,31. Electrochemical measurements were conducted using CR2032-type coin cells. Positive electrodes consisted of 80 wt% Na2Mn3O7, 10 wt% acetylene black, and 10 wt% polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF), which were coated on Al foil using N-methylpyrrolidone (NMP) as the solvent. Sodium was used as the negative electrode, with 1.0 M NaPF6 in ethylene carbonate (EC)/diethyl carbonate (DEC) (1:1 v/v%) as the electrolyte. The cells were cycled at a charge/discharge rate of C/20.

Ex situ X-ray absorption spectroscopy (XAS) and resonant inelastic X-ray scattering (RIXS) measurements were performed on samples without exposure to air at BL07LSU of SPring‐8. A bulk‐sensitive partial fluorescence yield (PFY) mode was employed for O K‐edge XAS. Extended X-ray absorption fine structure was conducted at the BL-9C Beamline of the Photon Factroy, KEK, Japan. SAED patterns were recorded using an electron microscope (Titan Cubed, FEI Co.) operated at 80 kV after transferring the samples without exposure to air.

All structures were calculated using DFT, as implemented in the Vienna Ab Initio Simulation Package (VASP)53,54. The projector-augmented wave pseudopotential and a plane-wave basis set with an energy cut-off of 520 eV were used55. The generalized gradient approximation (GGA) with the Perdew-Burke-Ernzerhof functional describes the exchange-correlation energy56,57. To remove the self-interaction error, the Hubbard U correction was applied to the d electrons of Mn atoms (Ueff = 3.9 eV)58,59. The k-point was sampled on a 3 × 3 × 5 grid for all calculations. The Grimme scheme (DFT-D3) was applied to include van der Waals corrections60. Crystal structures were visualized with VESTA software 61.

We constructed a 2 × 2 × 1 supercell (Na16-iMn24O56) to calculate a series of charged-structures of Na2-xMn3O7 (0 < x ≤ 2). All possible cation orderings (Na+) were searched in the Supercell program, with the exclusion of symmetrical duplicates62. Considering the large number of configurations in the initial search (e.g., 1670 for Na8Mn24O56), we conducted a multi-step calculation of total energies to determine the stable cation ordering for each structure. First, we simply calculated the total energies without geometry optimization and selected the 100 lowest-energy configurations for each charged-structure. Second, we optimized both the lattice and atomic positions of the selected configurations under a force convergence of 0.03 eV Å−1, where the energy cut-off and number of k points were reduced to 400 eV and 1 × 1 × 3, respectively. At this point, we screened out the 20 lowest-energy configurations for each structure. Finally, we reconducted the geometry optimization with a more reliable energy cut-off (520 eV) and k-point mesh (3 × 3 × 5) under a force convergence of 0.01 eV Å−1, identifying all the lowest-energy structures in the charge process.

The convex hull was constructed to identify the stable phases among the determined structures, with the formation energies (at 0 K) calculated as:

The formation of peroxide-like O22− in Na2-xMn3O7 was calculated by creating a short O-O bond in Na16-iMn24O56, as shown in Supplementary Figure 4b. After the atomic positions were fully relaxed, no other significant structural change was found except for the O-O dimer. The formation energy of O22− was calculated by:

Supplementary information is available for this paper at 10.1038/s41467-020-20643-w.

This work was financially supported by the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (MEXT), Japan; Grant-in-Aid for Specially Promoted Research No. 15H05701 and Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (S) No. 20H05673. This work was also supported by “Elements Strategy Initiative for Catalysts and Batteries (ESICB)”. M. O. was financially supported by JSPS KAKENHI (Grant Number 19H05816, 18K19124, and 18H03924), and the Asahi Glass Foundation. X-ray absorption/emission spectroscopy at BL07LSU of SPring-8 was performed by joint research in SRRO and ISSP, the University of Tokyo (Proposal No. 2020A7474, 2019B7456, 2019A7452, 2018B7590, and 2018A7560). The authors are grateful to J. Miyawaki and Y. Harada at the University of Tokyo for their support on the X-ray absorption/emission experiments.

M.O. and A.Y. conceived and directed the project. A.T. and B.M.B. synthesized and characterized Na2Mn3O7. X.M.S. conducted theoretical calculations. J.K. measured SAED patterns. A.T., K.K., and D.A. conducted synchrotron X-ray absorption/emission spectroscopy. All authors wrote the manuscript.

The whole datasets are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

The authors declare no competing interests.

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

6.

7.

8.

9.

10.

11.

12.

13.

14.

15.

16.

17.

18.

19.

20.

21.

22.

23.

24.

25.

26.

27.

28.

29.

30.

31.

32.

33.

34.

35.

36.

37.

38.

39.

40.

41.

42.

43.

44.

45.

46.

47.

48.

49.

50.

51.

52.

53.

54.

55.

56.

57.

58.

59.

60.

61.

62.

63.