- Altmetric

There is a great need to develop heterostructured nanocrystals which combine two or more different materials into single nanoparticles with combined advantages. Lead halide perovskite quantum dots (QDs) have attracted much attention due to their excellent optical properties but their biological applications have not been much explored due to their poor stability and short penetration depth of the UV excitation light in tissues. Combining perovskite QDs with upconversion nanoparticles (UCNP) to form hybrid nanocrystals that are stable, NIR excitable and emission tunable is important, however, this is challenging because hexagonal phase UCNP can not be epitaxially grown on cubic phase perovskite QDs directly or vice versa. In this work, one-pot synthesis of perovskite-UCNP hybrid nanocrystals consisting of cubic phase perovskite QDs and hexagonal phase UCNP is reported, to form a watermelon-like heterostructure using cubic phase UCNP as an intermediate transition phase. The nanocrystals are NIR-excitable with much improved stability.

Combining two or more different materials with different crystal structures into single nanoparticle with combined advantages is challenging. Here, the authors demonstrate one-pot synthesis of perovskite-upconversion hybrid nanocrystals consisting of cubic and hexagonal phases to form a watermelon-like heterostructure.

Introduction

There is increasing interest in developing heterostructured nanocrystals that combine two or more different materials into single nanoparticles with combined advantages. For example, heterostructured quantum dots (QDs) such as InP/ZnS, CdSe/CdS/ZnS, Si/CdS, PbSe/PbS, and CdSe/CdTe QDs have been synthesized and have exhibited significantly improved optical and electrical properties as compared to their individual constituents1,2. QDs are semiconductor nanoparticles whose excitons are limited to the Bohr radius in three-dimensional space, showing the quantum confinement effect3. Traditional quantum dots are made of compounds of the IV, II−VI, IV−VI, III−V, and I−III−VI groups, such as Si, CdTe, CdSe, ZnO, PbS, InP, CuInS2 QDs, etc4,5. In recent years, lead halide perovskite QDs have attracted much attention due to their excellent optical properties such as high photoluminescence quantum yield (PLQY) up to 100%6–8, large UV absorption cross section9, tunable emission over the entire visible spectrum10,11, long carrier diffusion length, and high carrier mobility12, which make them suitable for use in high-performance solar cells, light-emitting diodes (LEDs), lasers, and photodetectors10–14. However, perovskites have poor stability which limits their applications. Furthermore, their use in biological and medical applications is also very limited due to the low penetration depth of UV light in biological tissues. As compared to perovskite QDs, lanthanide-doped upconversion nanocrystals (UCNP) such as NaYF4:Yb,Tm have good stability and much higher multi-photon absorption efficiency under NIR excitation using low-cost continuous-wave (CW) lasers15,16. UCNP have been used in deep tissue fluorescence imaging and phototherapy due to deep penetration of NIR light in biological tissues17–20. However, UCNP have fluorescence emissions at fixed wavelengths only and their emission colors are not tunable and as such their use in multiplexed bioimaging or bioassays is limited. Combining perovskite QDs with UCNP to form hybrid nanocrystals with a heterostructure that are stable, NIR excitable and emission tunable may address the above-mentioned issues. Some studies have been performed to synthesize hybrid perovskite nanocrystals with semiconductor quantum dots with small crystal phase-mismatch such as CsPbBr3-CdS21, CsPbI3-PbS22, and CsPbBr3-TiO223 and bulk materials, such as MAPbI3-PbS24 and CsPbX3-PbS (X = Cl, Br, and I)25. Previous attempts have been made to synthesize UCNP-perovskite nanohybrids. The synthesis of NaYF4:Yb,Tm@CH3NH3PbBr3 nanohybrids via an innovative strategy consisting of using cucurbituril to anchor the perovskite nanoparticles firmly and closely to the upconversion nanoparticles has been previously achieved26. This is a typical A + B synthesis strategy. Material A and B were first synthesized, and an intermediate molecule cucurbituril was used to link the two materials to obtain AB composite material. The composite of perovskite NWs and UCNPs was synthesized at room temperature using PVP as a template27. First, the PVP-modified UCNPs were synthesized, and they were mixed with Pb(OA)2, which was a perovskite NWs precursor. l-cysteine was added and dispersed in isopropanol solution, and CH3NH3Br, another precursor of NWs, was added to obtain an AB composite. It is typical to synthesize material A first and then rely on the template method to get the composite material of AB during the synthesis process of material B. They all rely on the action of chemical bonds to connect the two synthetic materials, while we have creatively introduced the intermediate synthesis of crystal phase by controlling the crystal growth, and use the phase-transition characteristics to obtain heterojunction materials with excellent optical properties. However, it remains a challenge to synthesize perovskite/UCNP heterostructured nanocrystals due to the structural difference between cubic-phase perovskite QDs and hexagonal-phase UCNP and lack of a good understanding of the growth/formation mechanism. Going beyond perovskites and UCNP, this has posed a challenge in synthesizing heterostructured nanocrystals consisting of two or more different crystal phases with structural and lattice mismatch and a generic strategy must be developed.

In general, some stringent requirements must be met for making heterostructured nanocrystals: (I) crystal structure matching. Cubic-phase CsPbBr3 crystals can grow together with cubic-phase CdS or PbS crystals21,25; (II) lattice parameter matching. MAPbI3–PbS lattice mismatch was as small as 4.9%24; (III) similar reaction temperature and condition21. There are two strategies for synthesizing A–B hybrid nanocrystals with two different crystals A and B: (I) monodispersed A nanocrystals are synthesized first and then B is epitaxially grown on the surface of A nanocrystals to form a core-shell structure. (II) A and B are synthesized in the same solution simultaneously to produce hybrid nanocrystals with A embedded in B or B embedded in A. Both strategies require A and B to have the same crystal structure and closely matched structural and lattice parameters. For synthesizing perovskite–UCNP hybrid nanocrystals, in this work CsPbBr3-NaYF4:Yb,Tm, strategy II is adopted. Multiple CsPbBr3 perovskite QDs are embedded in the NaYF4:Yb,Tm UCNP to ensure there is sufficient absorption of NIR excitation light and efficient energy transfer from the UCNP to perovskite QDs. On the other side, it has been widely reported that CsPbBr3 perovskite QDs have very poor stability in water23,28. Embedding them in the UCNP will help prevent them from dissolving in water. The challenge to overcome is how to embed cubic-phase CsPbBr3 QDs in hexagonal-phase NaYF4:Yb,Tm UCNP to form hybrid nanocrystals in the same synthetic solution by one-pot synthesis. It is noted that the lattice mismatch between cubic-phase CsPbBr3 QDs and NaYF4:Yb,Tm UCNP is small, 5.9% only. Our hypothesis is those hybrid nanocrystals consisting of cubic-phase CsPbBr3 QDs and cubic-phase NaYF4:Yb,Tm UCNP can be first prepared in one-pot based on co-precipitation method due to small crystal structure mismatch and similarity in synthetic conditions. Phase transition of the UCNP from cubic phase to hexagonal phase is then induced by heating to a higher temperature, resulting in the formation of hybrid nanocrystals with cubic phase CsPbBr3 QDs embedded in hexagonal-phase NaYF4:Yb,Tm UCNP29.

In this work, we have demonstrated the successful synthesis of monodispersed and oval-shaped watermelon-like hybrid nanocrystals consisting of small cubic-phase CsPbBr3 QDs (watermelon seeds) embedded in hexagonal-phase NaYF4:Yb,Tm UCNP (watermelon pulp) with a thin NaYF4:Yb,Tm shell (watermelon skin). The hybrid nanocrystals emit characteristic green fluorescence of the CsPbBr3 QDs upon UV excitation and UV-blue fluorescence of the NaYF4:Yb,Tm UCNP upon NIR excitation, demonstrating the co-existence of both CsPbBr3 phase and NaYF4:Yb,Tm phase in the same structure, and green fluorescence upon NIR excitation when the NaYF4:Yb,Tm phase absorbs NIR light and transfers the energy to the CsPbBr3 phase. This has opened a new way of synthesizing heterostructured nanocrystals with two distinctly different crystal phases via an intermediate transition phase and the strategy could be applied to many other materials.

Results

Synthesis of CsPbBr3 QDs and NaYF4:Yb,Tm UCNP

CsPbBr3 QDs with regular cubic shape were first synthesized based on Kovalenko’s method30. The size of the CsPbBr3 QDs was 12.6 nm, and the diffraction peaks at 2θ = 15.2, 21.6, 26.5 30.6, 34.4, 37.8, 43.9, 46.7, 49.4, 54.5, and 59.3° correspond to diffractions from the {100}, {110}, {111}, {200}, {210}, {211}, {220}, {300}, {310}, {222}, and {321} planes of the cubic-phase CsPbBr3 (PDF# 00-054-0752) (Supplementary Figs. 1 and 2). To analyze the optical properties, the UV−vis absorption spectra, and the PL emission and excitation spectra (Supplementary Fig. 3) was obtained from the colloidal solution of the CsPbBr3 nanocrystals. The PL emission spectrum showed a peak position at 515 nm and showed a strong green fluorescence under 365 nm excitation (Supplementary Fig. 3A). The absorption onset of CsPbBr3 nanocrystals was around 510 nm (Supplementary Fig. 3B). The time-resolved PL decay of CsPbBr3 showed average PL decay lifetimes was 18.4 ns (Supplementary Fig. 3C and Supplementary Table 1). NaYF4:30%Yb,0.5%Tm nanocrystals were synthesized by the high-temperature co-precipitation method31. When the temperature reached 300 °C, NaYF4:30%Yb and 0.5%Tm nanocrystals with a size of about 5 nm were synthesized, and they emitted a weak fluorescence under 980 nm excitation (Supplementary Fig. 5). At 300 °C for 60 min, uniform NaYF4:30%Yb,0.5%Tm nanocrystals with a size of 32.5 nm were synthesized, and they emitted a strong blue fluorescence under 980 nm excitation (Supplementary Fig. 6). According to the XRD results (Supplementary Fig. 7), the diffraction peaks at 2θ = 17.2, 30.1, 30.8, 34.6, 39.6, 43.5, 46.5, 52.1, 53.1, 53.7, and 55.2° correspond to diffractions from the {100}, {110}, {101}, {200}, {111}, {201}, {210}, {002}, {300}, {211}, and {102} planes of the hexagonal-phase NaYF4 (JCPDS: 00-016-0334).

Synthesis of heterostructured nanocrystals

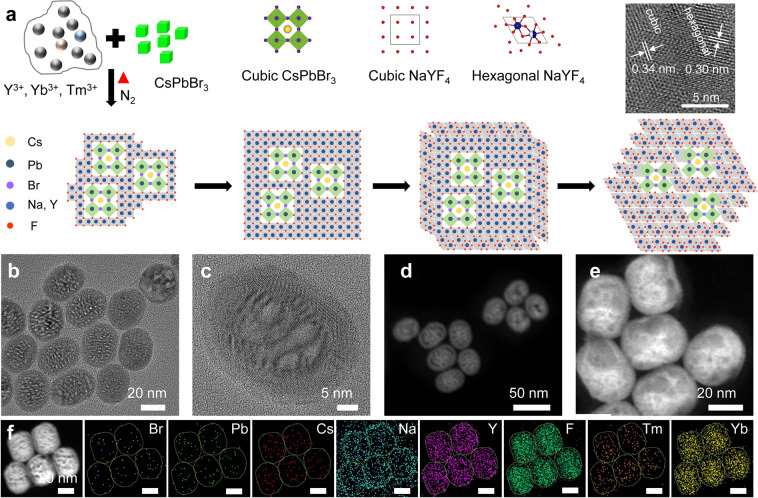

As shown in Fig. 1a, cubic-phase NaYF4:Yb,Tm UCNP can be epitaxially grown on the surface of cubic-phase CsPbBr3 QDs due to the similarity in the crystal structure and lattice. When the temperature is increased, UCNP is converted from cubic to hexagonal phase, while cubic-phase CsPbBr3 QDs remain unchanged so hexagonal-phase UCNP is formed on the surface of cubic-phase CsPbBr3 QDs. CsPbBr3-NaYF4:Yb,Tm hybrid nanocrystals were synthesized using a high-temperature co-precipitation method. Their formation and crystal structures were studied. CsPbBr3 QDs with regular cubic shape were first synthesized based on Kovalenko’s method (Supplementary Fig. 1)11, and then added to the precursor solution for UCNP synthesis which consists of various lanthanide ions such as Y3+, Yb3+, and Tm3+ and surfactants, such as oleic acid (OA) and octadecylene (ODE). As shown in Fig. 1b–e, heterostructured nanocrystals were formed with the CsPbBr3 QDs embedded in the NaYF4:Yb,Tm UCNP, to form a structure similar to that of watermelon with multiple seeds. The average size of the nanocrystals was ~37 nm, and the outer shell was ~3.7-nm thick (Fig. 1c). CsPbBr3 QDs were found to be in the middle region of the nanocrystals with distinct crystal boundary formed between the CsPbBr3 QDs and UCNP from the bright- and dark-field TEM images. The heterostructure interface can be clearly seen from the HRTEM diagram (Supplementary Fig. 8), and the area segmented by the arc presents obvious light and dark patterns. Above the arc is the cubic-phase CsPbBr3 crystals and below the arc is the hexagonal-phase NaYF4:Yb,Tm crystals. The cubic-phase NaYF4:Yb,Tm is a metastable crystalline phase, which led to the formation of irregular small cubic-phase CsPbBr3 crystals within the heterogeneous junction, thus making the interface of heterogeneous junction irregular. From HRTEM, STEM, and elemental imaging results (Supplementary Fig. 9), it can be clearly seen that the perovskites in the heterostructured nanocrystals were small irregular particles with a size of 6–12 nm. At 250 °C, the heterostructured nanocrystals were composed of a cubic-phase UCNPs and cubic-phase perovskites. The cubic-phase UCNPs has a high-temperature metastable crystalline phase, which led to the irregular growth of perovskites in the heterojunction. Subsequently, under the effects of thermodynamics (250–300 °C), the cubic-phase UCNP transited to the hexagonal phase. At this time, the epitaxial growth was mainly due to the hexagonal-phase UCNP, and most of the perovskite stopped growing due to the mismatch of crystal phases. As shown in Fig. 1f, eight elements including Br, Pb, Cs, Na, Y, F, Tm, and Yb were distributed in the nanocrystal structure (Supplementary Fig. 10). The elemental mapping images showed that Na, Y, F, Tm, and Yb ions which constitute the NaYF4:Yb,Tm UCNP were uniformly distributed throughout the hybrid nanocrystals, while Br, Pb, and Cs ions which make up CsPbBr3 QDs were located in the middle part. This could also be seen from the images of single-particle element imaging (Supplementary Fig. 11), supporting that the hybrid nanocrystals were formed with the CsPbBr3 QDs embedded in the NaYF4:Yb,Tm UCNP. According to the XPS results, the concentration ratio of CsPbBr3 and NaYF4:Yb,Tm in the heterostructured nanocrystals was 1:59. (Supplementary Table 2).

Synthesis of CsPbBr3-NaYF4:Yb,Tm hybrid nanocrystals.

a Schematic showing the formation of heterostructured CsPbBr3–NaYF4: Yb,Tm nanocrystals, b, c TEM and d, e STEM images of heterostructured CsPbBr3–NaYF4:Yb,Tm nanocrystals. f Elemental mapping of heterostructured CsPbBr3–NaYF4:Yb,Tm nanocrystals. Scale bars in f, 20 nm.

Nanocrystal heterostructure formation during heat treatment

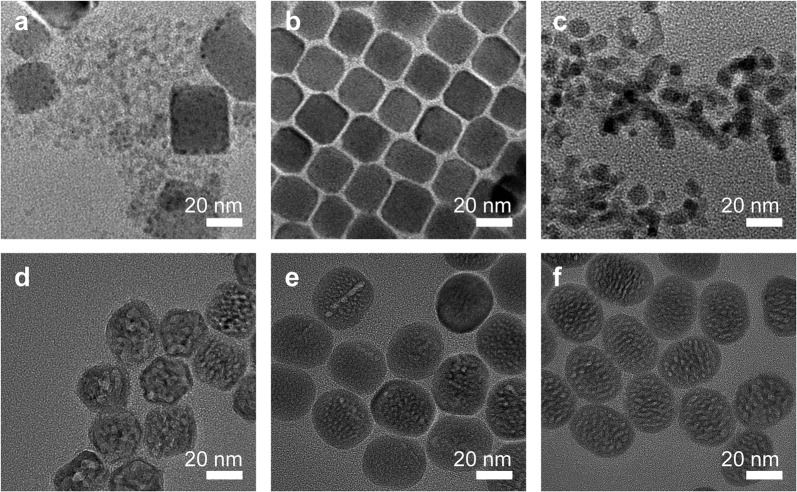

The formation of the CsPbBr3-NaYF4:Yb,Tm hybrid nanocrystals was studied by TEM measurement of the samples collected at different temperatures during the heat-treatment process. From the literature, it was reported that cubic-phase CsPbBr3 crystals (5.83 Å) and cubic-phase NaYF4 crystals (5.47 Å) have a small lattice mismatch of ~5.9%, suggesting that theoretically it is possible to grow cubic phase CsPbBr3 crystals on cubic-phase NaYF4 crystals epitaxially or vice versa32–34. In this study, pre-made cubic-phase CsPbBr3 QDs were added to the precursor solution to synthesize NaYF4:Yb,Tm UCNP, so it is a high probability that NaYF4:Yb,Tm crystals were grown on the surface of CsPbBr3 QDs, evidenced from the dark spots formed on the surface of the cubic-shape nanocrystals at 150 °C and 200 °C, as shown in Fig. 2a, b. This is similar to cubic-phase CsPbX3–PbS hybrid nanocrystals formed under a similar condition25. The temperature was subsequently increased to 250 °C, resulting in much smaller nanocrystals with a size of ~12 nm (Fig. 2c). Besides poor chemical stability in water, poor thermostability of CsPbBr3 QDs has also been well reported35,36. High temperature may cause the oxidation and hydration and eventually the decomposition of CsPbBr3 QDs. At 250 °C, the size of the nanocrystals was apparently much smaller as compared to a lower temperature, suggesting that CsPbBr3 QDs started to decompose partially. This is usually considered a problem for perovskite QDs; however, in this study, the smaller size of perovskite QDs caused by partial decomposition makes it possible to synthesize small perovskite–UCNP hybrid nanocrystals. On the other side, the cubic phase is dominant in the NaYF4 nanocrystals formed at 250 °C, as previously reported29,37,38. The small hybrid nanocrystals served as the seeds for further growth of the NaYF4:Yb,Tm UCNP. The average size of the nanocrystals increased to 30.6 nm when the temperature reached 300 °C (Fig. 2d). With the extension of the insulation time to 30 and 60 min, the size continued to increase to 34.5 nm and 37.1 nm, respectively (Fig. 2e, f). Their morphology changed from square or hexagonal to ellipsoidal shape. In addition, multiple cores were clearly observed in the middle region of the perovskite–UCNP hybrid nanocrystals during the thermal insulation process (Supplementary Fig. 12), which was consistent with the previous elemental mapping results.

Nanocrystal heterostructure formation during heat treatment.

TEM images of heterostructured CsPbBr3–NaYF4: Yb,Tm nanocrystals collected during the synthesis at different temperatures. a 150 °C, b 200 °C, c 250 °C, d 300 °C—0 min, e 300 °C-30 min, f 300 °C—60 min.

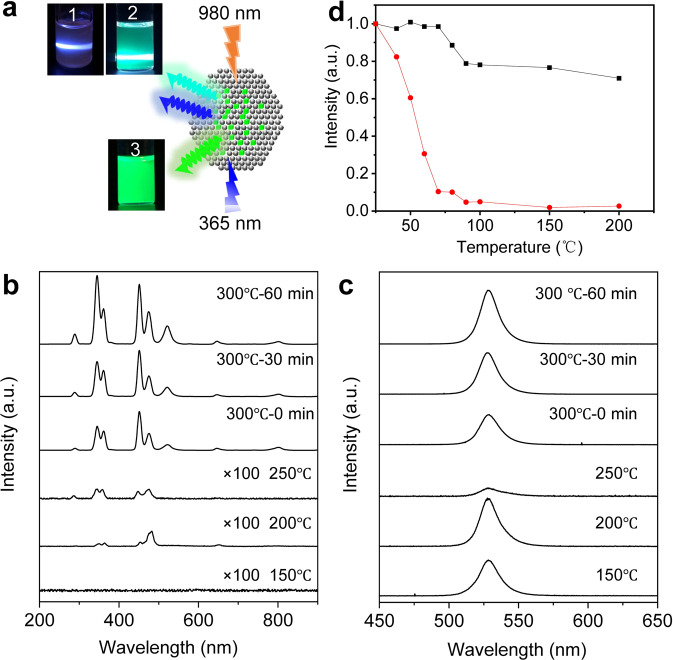

Luminescence emission profile

The fluorescence emission of nanocrystals is dependent on the crystal structure and phases. Fluorescence emission spectra of the perovskite–UCNP hybrid nanocrystals collected at different temperatures were measured under excitation at 980 nm and 365 nm, respectively, and used to study the crystal phase formation and transition during the synthesis of the hybrid nanocrystals. As shown in Fig. 3a, the hybrid nanocrystals had three different states of luminescence: it emitted blue and cyan fluorescence under 980 nm excitation and green fluorescence under 365 nm excitation. When the temperature was increased from 150 °C to 250 °C, upconversion luminescence was weak and there was no characteristic green fluorescence emission of CsPbBr3 QDs at 515 nm under 980 nm excitation, indicating that there is no energy transfer from the NaYF4:Yb,Tm UCNP to CsPbBr3 QDs due to the low luminescence efficiency of cubic-phase NaYF4:Yb,Tm UCNP formed at low temperature38,39. The intensity of the green fluorescence of CsPbBr3 QDs under 365 nm excitation decreased due to the partial decomposition of the QDs. When the temperature was further increased to 300 °C, the hybrid nanocrystals exhibited UV/blue upconversion fluorescence under 980 nm excitation (Fig. 3b), with emission peaks located at 292 nm (1I6 → 3F4), 347 nm (1I6 → 3F4), 362 nm (1D2 → 3H6), 450 nm (1D2 → 3F4), and 478 nm (1G4 → 3H6), and green fluorescence at 522 nm corresponding to the emission of CsPbBr3 QDs, suggesting a significant energy transfer from the NaYF4:Yb,Tm UCNP to CsPbBr3 QDs and formation of hexagonal-phase NaYF4:Yb,Tm UCNP. It has been reported that hexagonal-phase NaYF4:Yb,Tm UCNP emits much stronger upconversion fluorescence as compared to its cubic phase38–40. During the process of maintaining the temperature at 300 °C for 0 to 60 min, the intensity of the green fluorescence emission peak increased, suggesting an increased energy transfer from the NaYF4:Yb,Tm UCNP to CsPbBr3 QDs. Meanwhile, at 300 °C, the hybrid nanocrystals emitted strong green fluorescence at 525 nm under 365 nm excitation which was corresponding to CsPbBr3 QDs (Fig. 3c). The absorption of the heterostructure composite of CsPbBr3–NaYF4:Yb,Tm nanocrystals were around 510 nm. The excitation spectrum showed that the heterostructure composite of CsPbBr3–NaYF4:Yb,Tm nanocrystals exhibited the strongest peak at 475 nm monitored at the emission wavelength of 525 nm, which is in good agreement with the result from the UV–vis absorption spectrum (Supplementary Fig. 13). During the process of nanocrystals formation and growth, the heterostructured nanocrystal at 250 °C was composed of cubic-phase UCNPs and cubic-phase CsPbBr3. When the temperature increased to 300 °C and incubated for 60 min, the cubic-phase UCNPs changes to the hexagonal phase and resulted in the heterostructured nanocrystals of the hexagonal-phase UCNPs and cubic-phase CsPbBr3 formation. The PLQY of these heterostructured nanocrystals under excitation at 980 nm were as follows: 150 °C (0%), 200 °C (0%), 250 °C (0.02%), 300 °C—0 min (0.15%), and 300 °C—60 min (0.25%) (Supplementary Table 3). Similarly, the PLQY of these heterostructured nanocrystals increased from 0.02% to 0.139% under the 980 nm excitation. This PLQY increase was a result of the NaYF4 phase transition from cubic to hexagonal. The hexagonal-phase NaYF4 has a much higher fluorescence efficiency as compared to its cubic phase. The PLQY of these heterostructured nanocrystals under 365 nm excitation were as follows: 150 °C (53%), 200 °C (35%), 250 °C (12%), 300 °C—0 min (23%), and 300 °C—60 min (21%) (Supplementary Table 3). Under the excitation of 365 nm, the peak position of heterostructured nanocrystals was 525 nm. The PLQY increased from 12% to 23% during the heterostructured nanocrystal phase-transition process. The fluorescence quantum efficiency of the conventional CsPbBr3 nanocrystals was 65%, and fluorescence quenching occurred after CsPbBr3 nanocrystals was kept at 300 °C for 60 min (Supplementary Table 3 and Supplementary Table 4). On the other hand, the PLQY of the perovskite within the heterostructured nanocrystals excited by 365 nm was about 21% after being kept at 300 °C for 60 min far higher than that of the conventional CsPbBr3 nanocrystals at 300 °C for 60 min (Supplementary Table 4). The conventional CsPbBr3 nanocrystals were kept at 300 °C for 60 min, resulting in very small-sized particles and very weak fluorescence (Supplementary Fig. 4). This is because the conventional CsPbBr3 nanocrystals shrank in size, dissolved, and their crystal structure was destroyed at 300 °C after 60 min. The heterojunctured nanocrystals have strong fluorescence at the 525 nm peak under 365 nm excitation, which fully indicated that the cubic-phase and hexagonal-phase UCNP have an obvious protective effect on CsPbBr3 nanocrystals at high temperature. The hybrid nanocrystals were reheated reheated to different temperatures of 25 °C, 40 °C, 50 °C, 60 °C, 70 °C, 80 °C, 90 °C, 100 °C, 150 °C, and 200 °C, and compared to pure CsPbBr3 perovskite QDs. When the temperature was increased to 200 °C, the intensity of CsPbBr3 QDs quickly reduced to 2% while the intensity of the hybrid nanocrystals dropped to 71% only, showing the protection of the CsPbBr3 QDs by the UCNP at high temperature (Fig. 3d and Supplementary Fig. 14). Relative fluorescence intensity of the heterostructured CsPbBr3–NaYF4:Yb,Tm hybrid nanocrystals still maintained around 90% during the heating process under 980 nm excitation (Supplementary Fig. 15). The hybrid nanocrystals maintained the luminescent properties of both perovskite QDs and UCNP and improved the stability of perovskite QDs at high temperatures.

Fluorescence of CsPbBr3–NaYF4:Yb,Tm hybrid nanocrystals.

a Photographs showing different color fluorescence emitted from the heterostructured CsPbBr3-NaYF4:Yb,Tm nanocrystals collected during the synthesis under different conditions (state 1, 300 °C—0 min, state 2, 300 °C—60 min, both under 980 nm excitation, state 3, 300 °C—60 min, under 365 nm excitation). b, c Fluorescence emission spectra of heterostructured CsPbBr3–NaYF4:Yb,Tm nanocrystals at different temperatures under 980 nm and 365 nm excitations, respectively. d Fluorescence intensity of CsPbBr3 nanocrystals (red) and heterostructured CsPbBr3–NaYF4:Yb,Tm nanocrystals (black) collected at different temperatures under 365 nm excitation.

Exploration of the energy-transfer mechanism

The Förster resonance energy transfer (FRET) and the emission reabsorption (ERA) were the two main energy-transfer processes. The changes in fluorescence lifetime are directly associated with FRET, but not with ERA. Efficient FRET between NaYF4:Yb,Tm donors and CsPbBr3 acceptors will only take place at short distances. Indeed, the fluorescence average lifetime reduction of the blue emission at 478 nm from 0.66 ms of the NaYF4:30%Yb,0.5%Tm nanocrystals to 0.29 ms of the CsPbBr3–NaYF4:Yb,Tm nanocrystals (Supplementary Fig. 16 and Supplementary Table 5) suggested that the energy transfer from NaYF4:Yb,Tm to CsPbBr3 in the heterostructure follows a typical FRET process27,41. The FRET efficiency can be calculated with the equation Eff = 1 − τD–A/τD, where Eff is the energy transfer efficiency, τD–A is the effective lifetime of a donor conjugated with an acceptor, and τD is the effective lifetime of a donor in the absence of an acceptor. The FRET efficiency of the CsPbBr3–NaYF4:Yb,Tm nanocrystals calculated was 56%, which justifies our design for an efficient energy transport strategy. The fluorescence lifetime of the mixed CsPbBr3 and NaYF4:Yb,Tm is 0.59 ms, which only reduces 0.07 ms compared with the NaYF4:30%Yb,0.5%Tm NPs fluorescence lifetime of 0.66 ms, and the efficiency of FRET is calculated to be 11%, far lower than the energy transfer efficiency of FRET in the heterogeneous junction (Supplementary Figs. 16, 17 and Supplementary Tables 5, 6). Therefore, the energy transfer process of the mixed CsPbBr3 and NaYF4:Yb,Tm is mainly EAU, which is different from that of FRET in heterostructured CsPbBr3-NaYF4:Yb,Tm hybrid nanocrystals. In addition, the fluorescence lifetime of the perovskites has increased from 18 ns to 0.37 ms (Supplementary Fig. 18 and Supplementary Table 7).

By changing the number of perovskites, we have changed the ratio between the perovskite and UCNP in the heterostructured nanocrystals, and obtained 0.2-fold and fivefold CsPbBr3–NaYF4:Yb,Tm nanocrystals. The fluorescence lifetime of the onefold heterostructured nanocrystal is 0.29 ms (Supplementary Fig. 19 and Supplementary Table 8). The fluorescence lifetime of the 0.2-fold heterostructured nanocrystal increased to 0.49 ms, while that of the fivefold heterostructured nanocrystal decreased to 0.25 ms (Supplementary Table 8). As compared to the FRET efficiency of the onefold heterostructured nanocrystal, 56%, the FRET efficiency of the 0.2-fold heterostructured nanocrystal was reduced to 25.8%. On the other hand, the FRET efficiency of the fivefold heterostructured nanocrystal increased to 62.1% (Supplementary Table 9). Therefore, it shows that the decrease in the perovskite/UCNP ratio resulted in increased fluorescence lifetime and decreased FRET efficiency. Compared to the fluorescence spectra of pure UCNP under 980 nm excitation, the absorption of the fluorescence emitted from UCNP increases with the increase of the perovskite amount (Supplementary Fig. 20).

Regulation of optical properties

The heterojunction nanocrystals synthesized by us could undergo anion exchange with Cl− and I− to control the energy transfer and luminescence performance. Under the 980 nm excitation, the 525 nm fluorescence peak emitted by the perovskites within the heterogeneous crystals was shifted to 578 nm after the addition of I−. On the other hand, this same peak was shifted to 478 nm after the addition of Cl− (Supplementary Fig. 21A). During the anion exchange in CsPbBr3 nanocrystals with the introduction of I− into the heterogeneous crystal, and the fluorescence lifetime of CsPbBr3 nanocrystals in the heterojunction became longer. However, the introduction of Cl− into the heterojunction shortened the fluorescence lifetime of CsPbBr3 nanocrystals in the heterogeneous crystal42, thus affecting the energy transfer efficiency. Under the 365 nm excitation, the 525 nm fluorescence peak emitted from the heterogeneous crystal was blue shifted to 479 nm and red shifted to 578 nm, respectively (Supplementary Fig. 21B). Therefore, this heterojunction nanocrystal structure was able to regulate the energy-transfer process and optical properties from NaYF4:Yb,Tm to CsPbBr3 nanocrystals via anion exchange. Compared with pure UCNPs, heterogeneous crystals can not only regulate their optical properties through anion exchange but also change the composition of CsPbX3 nanocrystals in heterogeneous crystals. With the ratios of perovskites to UCNPs kept unchanged and only the perovskite composition was changed, we have obtained the heterostructured CsPbBr2/Cl1-NaYF4:Yb,Tm nanocrystals and the heterostructured CsPbBr2/I1-NaYF4:Yb,Tm nanocrystals. The size of the heterostructured CsPbBr2/Cl1-NaYF4:Yb,Tm and CsPbBr2/I1-NaYF4:Yb,Tm nanocrystals were 42.3 nm and 39.6 nm, respectively (Supplementary Fig. 24A, B). The irregular small particles of perovskite in the heterostructured nanocrystals were also observed. According to the fluorescence spectrum under the excitation of 980 nm (Supplementary Fig. 24C, D), the emission peak of the perovskites in the heterostructured CsPbBr2/Cl1-NaYF4:Yb,Tm nanocrystals was shifted left to 477 nm, while the emission peak of the perovskites in the heterostructured CsPbBr2/I1-NaYF4:Yb,Tm nanocrystals was shifted right to 542 nm. Under 365 nm excitation, the fluorescence peaks of the heterostructured CsPbBr2/Cl1-NaYF4:Yb,Tm and CsPbBr2/I1-NaYF4:Yb,Tm nanocrystals were 478 nm and 542 nm (Supplementary Fig. 24E, F), respectively. These peaks matched with the upconversion fluorescence peaks of CsPbX3 in the heterostructured nanocrystals which indicated that the NaYF4:Yb,Tm has a protective effect on the structure of perovskite at high temperature. The fluorescence lifetimes of the heterostructured CsPbBr2/Cl1-NaYF4:Yb,Tm and CsPbBr2/I1-NaYF4:Yb,Tm nanocrystals at the 478 nm peak were 0.23 ms and 0.48 ms, respectively (Supplementary Fig. 24G-H and Supplementary Table 10). Therefore, we have shown that our synthesis strategy is compatible to synthesize heterogeneous junctions composed of different types of UCNPs and perovskites. If the aforementioned three conditions were met, different types of heterogeneous junction products such as PbS-UCNPs, CdS-UCNPs can be obtained.

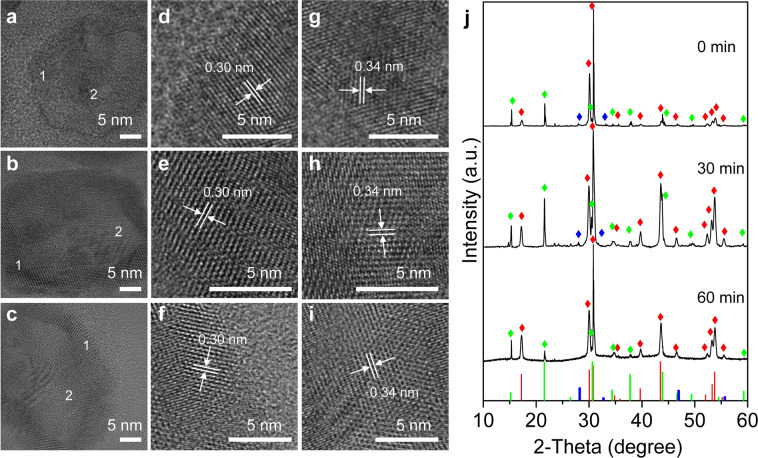

Phase transition

At 250 °C, the heterojunction nanocrystals mainly contained cubic-phase CsPbBr3 crystals and cubic-phase NaYF4:Yb,Tm crystals according to the standard data of JCPDS# 00-054-0752 and JCPDS# 00-016-0334 (Supplementary Fig. 25). The 2θ of the {100} crystal plane of the cubic-phase CsPbBr3 crystals has increased from 15.18° to 15.3°, and the lattice spacing has decreased. On the other hand, the 2θ of the {100} crystal plane of the cubic-phase NaYF4:Yb,Tm crystals has decreased from 28.2° to 27.8°, which further indicated that the lattice strain was generated by the heterojunction nanocrystals at 250 °C. In order to understand the phase transition during the process of maintaining the temperature at 300 °C for 0 to 60 min, lattice spacing and XRD measurements for the above samples were performed. In this process, as seen in Fig. 4a–i, the lattice distance on the surface of the hybrid nanocrystals was 0.3 nm in accordance with the {110} lattice spacing of hexagonal-phase NaYF4 UCNP (JCPDS: 00-016-0334), while the lattice distance in the middle was 0.34 nm corresponding to the {111} lattice spacing of cubic-phase CsPbBr3 QDs (JCPDS: 00-054-0752). The high-resolution TEM images confirmed that the two crystals were grown together and well combined which is very important to ensure a highly efficient energy transfer between them when excited at 980 nm. At 300 °C, XRD results in Fig. 4j showed that the nanocrystals mainly contained cubic-phase CsPbBr3 crystals and hexagonal-phase NaYF4 crystals, according to the standard data of JCPDS# 00-054-0752 and JCPDS# 00-016-0334. Very weak peaks of cubic-phase NaYF4 crystals (JCPDS: 01-077-2042) were also observed. With the extension of the thermal insulation time, the cubic-phase NaYF4 crystals transformed to hexagonal-phase NaYF4 crystals and finally disappeared, resulting in an increase in the relative proportion of hexagonal NaYF4 crystals (Supplementary Fig. 26), so only cubic-phase CsPbBr3 crystals and hexagonal-phase NaYF4 crystals co-existed in the hybrid nanocrystals. The process of phase transition led to the formation of crystal boundary in the nanocrystal structure, which was confirmed with HRTEM results. When cubic-phase NaYF4 crystals transformed to the hexagonal phase with high fluorescence efficiency, upconversion fluorescence was enhanced, which was also consistent with the results of fluorescence measurement.

Structural analysis of CsPbBr3-NaYF4:Yb,Tm hybrid nanocrystals.

HRTEM images of heterostructured CsPbBr3-NaYF4:Yb,Tm nanocrystals collected during the synthesis after heated at 300 °C for different time: a 0 min, b 30 min, c 60 min. d–f Enlarged images of region 1 in a, b, and c, respectively. g–i Enlarged images of region 2 in a, b, and c, respectively. j X-ray diffraction (XRD) patterns of the three samples. Hexagonal NaYF4, red color (JCPDF#00-016-0334), cubic NaYF4, blue color (JCPDF #01-077-2042), cubic CsPbBr3, green color (JCPDF #00-054-0752).

Stability study

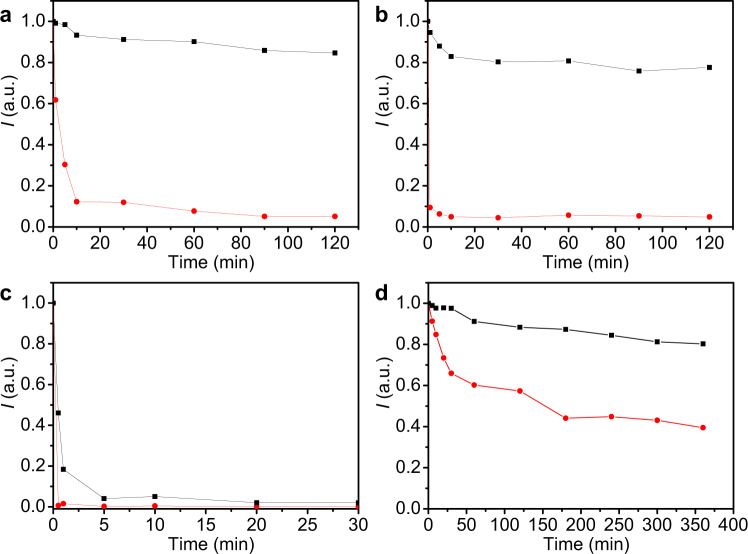

The stability in a mixture solution of cyclohexane and ethanol with a ratio of 9:1 or 1:1 has significantly improved as compared to the conventional CsPbBr3 nanocrystals. We have studied the stability of heterostructure composite of CsPbBr3-NaYF4:Yb,Tm nanocrystals in a mixture solution of cyclohexane and ethanol with a ratio of 9:1 (Fig. 5a and Supplementary Fig. 27) also. The relative fluorescence intensity of the CsPbBr3 nanocrystals decreased to 12% at 10 min and 5% at 120 min in the mixture solution. On the other hand, the heterostructure composite of CsPbBr3-NaYF4:Yb,Tm nanocrystals has managed to maintain a relative fluorescence intensity of 93% at 10 min and 85% at 120 min. This result suggests good stability in a mixture of cyclohexane and ethanol with a ratio of 9:1. Furthermore, the relative fluorescence intensity of the CsPbBr3 nanocrystals quickly decreased to 10% at 1 min and 5% at 120 min in a mixture of cyclohexane and ethanol with a ratio of 1:1 (Fig. 5b and Supplementary Fig. 27), whereas the heterostructure composite of CsPbBr3-NaYF4:Yb,Tm nanocrystals has maintained a relative fluorescence intensity of 95% at 1 min and slowly decrease to 80% after 2 h. This result suggests excellent fluorescence stability in a mixture of cyclohexane and ethanol with a ratio of 1:1. The stability of the heterostructure composite of CsPbBr3–NaYF4:Yb,Tm nanocrystals in water was still less than ideal. As shown in Fig. 5c, the relative fluorescence intensity of CsPbBr3 nanocrystals in water solution has decreased to <1% after 30 s, while the relative fluorescence intensity of the heterostructure composite of CsPbBr3-NaYF4:Yb,Tm nanocrystals was able to remain at 46% in water solution (Supplementary Fig. 28). Even though the relative fluorescence intensity decreased to about 4% in 5 min eventually, the stability of these heterostructured nanocrystals in the water has shown slight improvement as compared to the conventional CsPbBr3 nanocrystals. From the results of solvent stability experiments, it can be inferred that there were bare perovskite crystals on the heterogeneous crystal surface that were not completely covered by NaYF4:Yb,Tm nanocrystals. Upon contact with the water molecules, the water molecules infiltrated into the heterogeneous crystal structure along with the perovskite found on the crystal surface. Thus, the perovskite crystal structure in the heterogeneous junction was destroyed and reduced the fluorescence significantly. In addition, we have studied light stability. Under continuous ultraviolet light, the CsPbBr3 nanocrystals only have a 40% relative fluorescence intensity after 360 min, while heterostructure composite of CsPbBr3–NaYF4:Yb,Tm nanocrystals maintained an 80% fluorescence intensity (Fig. 5d and Supplementary Fig. 29). This result suggests that the heterostructured nanocrystals have good light stability.

Stability analysis of CsPbBr3–NaYF4:Yb,Tm hybrid nanocrystals.

PL intensity test was used to monitor the stabilities of CsPbBr3 (red) and the heterostructure composite of CsPbBr3–NaYF4:Yb,Tm nanocrystals (black) in cyclohexane and ethanol (v/v = 9: 1) mixed solvent (a), cyclohexane and ethanol (v/v = 1: 1) mixed solvent (b), water solvent (c), and continuous ultraviolet light irradiation (d) under 365 nm excitation.

Discussion

In summary, heterostructured CsPbBr3–NaYF4:Yb,Tm nanocrystals were synthesized in one-pot with cubic-phase CsPbBr3 QDs embedded in hexagonal-phase NaYF4:Yb,Tm UCNP to form a structure of watermelon with multiple seeds, using cubic-phase NaYF4:Yb,Tm UCNP as an intermediate transition phase. Different phase crystals can not grow on each other epitaxially to form a heterostructure due to unmatched crystal structure and lattice. Synthesizing heterostructured nanocrystals with two or more different crystal phases remains a challenge. We have successfully demonstrated that cubic-phase perovskite QDs and hexagonal-phase UCNP could be combined into a single nanocrystal by introducing an intermediate transition phase into the synthesis. Cubic-phase UCNP was grown on cubic-phase perovskite QDs to form single nanocrystals, followed by a phase transition from cubic-phase UCNP to hexagonal-phase UCNP by heating to a higher temperature, to obtain monodispersed and heterostructured perovskite–UCNP nanocrystals with multiple cubic-phase perovskite QDs embedded in hexagonal-phase UCNP. Going beyond this, a generic strategy has been developed to synthesize heterostructured nanocrystals with different phases based on phase transition and this could be readily applied to many other materials.

Methods

Chemicals and materials

Cesium carbonate (Cs2CO3, 99.9%), lead bromide (PbBr2, 99.9%), lead chloride (PbCl2, 99.9%), lead iodide (PbI2, 99.9%), yttrium acetate ((CH3CO2)3Y·xH2O, 99.9%), ytterbium acetate ((CH3CO2)3Yb·4H2O, 99.9%), thulium(III) acetate ((CH3CO2)3Tm·xH2O, 99.9%), sodium hydroxide (NaOH, 99%), ammonium fluoride (NH4F, 98%), octadecene (ODE, 95%), oleic acid (OA, 90%), oleylamine (OAm, 98%), oleylamine chloride (OAmCl, 99%), oleylamine iodide (OAmI, 99%), cyclohexane (99.9%), and toluene (99.9%) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich and used as received without further purification.

Synthesis of CsPbBr3 perovskite nanocrystals

Cs-oleate was synthesized by reacting Cs2CO3 (0.2 g) with OA (0.6 mL) in octadecene (7.5 mL) and pre-heated to 120 °C before injection. PbBr2 (0.188 mmol) and 5 mL of ODE were loaded into a 100 mL 3-neck flask, dried under vacuum at 120 °C for 1 h, and mixed with vacuum-dried OAm (0.5 mL) and OA (0.5 mL) under a N2 atmosphere. The temperature was raised to 150 °C, and 0.6 mL of Cs-oleate solution was rapidly injected. After 5 s, the reaction mixture was cooled in an ice-water bath. Nanocrystals were precipitated by centrifugation at 12,000 rpm and re-dispersed in 10 mL of cyclohexane. Other samples (CsPbBr2Cl1 and CsPbBr2I1) with different ratios of Br/Cl or I = 2/1 were synthesized by the same strategy. The other conditions for synthesis and purification remain the same.

Synthesis of heterostructured CsPbBr3- NaYF4: Yb,Tm nanocrystals

First, 0.695 mmol Y(CH3CO2)3, 0.30 mmol Yb(CH3CO2)3, and 0.005 mmol Tm(CH3CO2)3 were mixed with 6 mL of oleic acid and 15 mL of octadecene in a 50-mL flask and heated to 150 °C. After cooled down to room temperature, 10 mL of methanol solution (100 mg NaOH and 150 mg NH4F) were slowly added into the flask, and the solution was stirred for 10 min. The solution was subsequently heated to remove methanol and degassed at 120 °C for 20 min. In all, 1 mL of CsPbBr3 solution was hot-injected into the precursor solution and then heated to 300 °C for 1 h under N2 environment. The product was washed twice with cyclohexane by centrifugation for 10 min and dispersed in 20 mL of cyclohexane for further use. The ratio between CsPbBr3 and NaYF4: Yb,Tm nanocrystals could be adjusted.

Synthesis of heterostructured CsPbBr2Cl1- NaYF4: Yb,Tm and heterostructured CsPbBr2I1- NaYF4:Yb,Tm nanocrystals

In total, 0.695 mmol (CH3CO2)3Y, 0.30 mmol (CH3CO2)3Yb, and 0.005 mmol (CH3CO2)3Tm were mixed with 6 mL of oleic acid and 15 mL of octadecene in a 50-mL flask and heated to 150 °C. After cooled down to room temperature, 10 mL of methanol solution (100 mg NaOH and 150 mg NH4F) was slowly added into the flask, and the solution was stirred for 10 min. The solution was subsequently heated to remove methanol and degassed at 120 °C for 20 min. In all, 1 mL of CsPbBr2I1 or CsPbBr2I1 solution was hot-injected into the precursor solution and then heated to 300 °C for 1 h under N2 environment. The product was washed twice with cyclohexane by centrifugation for 10 min and dispersed in 20 mL of cyclohexane for further use.

Anion exchange of heterostructured CsPbBr3- NaYF4: Yb,Tm nanocrystals

The anion-exchange reactions were performed in a 10-mL glass bottle. The heterostructured CsPbBr3- NaYF4: Yb,Tm nanocrystals (5 mL, 0.05 mol/L) were used as the precursor. For anion exchange, OAmI or OAmCl (20 mg) was dissolved in cyclohexane (20 mL) as the anion source, and add 850 μL of OAmI or 700 μL of OAmCl solution into the heterostructured nanocrystals solution (5 mL) to achieve anion exchange. Anion exchange could be completed in a time period ranging from tens of seconds to a few minutes. After the reaction, the emission peaks of the solution were detected by a spectrofluorometer.

Characterization

TEM was performed on an FEI Tecnai G2 F20 electron microscope operating at 200 kV. Low-voltage high-resolution STEM measurement was carried out on a double-aberration-corrected TitanTM cubed G2 60−300 S/TEM equipped with Super-XTM technology. The available point resolution is ~0.1 nm at an operating voltage of 60 kV. XRD was measured with a Bruker AXS D8 X-ray diffractometer equipped with monochromatized Cu Kα radiation (λ = 1.5418 Å). XPS was performed using an achromatic Al Kα source (1486.6 eV) and a double-pass cylindrical mirror analyzer (ULVACPHI 5000 Versa Probe) (Japan). Heterostructured nanocrystals were dissolved in cyclohexane solution at a concentration of 0.05 mol/L, and the upconversion fluorescence spectrum, down-conversion fluorescence spectrum, absorption spectrum, excitation spectrum, and fluorescence lifetime were tested and characterized. Ultraviolet and visible absorption (UV–vis) spectra were recorded with a Shimadzu UV-3600 plus spectrophotometer equipped with an integrating sphere under ambient conditions. Photoluminescence excitation and emission spectra and fluorescence decays were recorded on a FLS980 spectrometer (Edinburgh) equipped with both continuous xenon (450 W) and pulsed flash lamps. Upconversion fluorescence emission spectra were acquired under 980 nm excitation with a CW diode laser (2 W/cm2). Measurement of absolute up- and down-conversion PLQY of nanocrystals was performed using a standard barium sulfate-coated integrating sphere (Edinburgh). The sample chamber was mounted to a FLS980 spectrophotometer. Lifetime was measured with a customized UV to mid-infrared steady-state and phosphorescence lifetime spectrometer (FSP920-C, Edinburgh) equipped with a digital oscilloscope (TDS3052B, Tektronix) and a tunable mid-band Optical Parametric Oscillator pulsed laser as the excitation source (410–2400 nm, 10 Hz, pulse width ≤5 ns, Vibrant 355II, OPOTEK). Fluorescence decay was measured on a Nikon Ni-U Microfluorescence Lifetime system with a 375 nm picosecond laser and a time-correlated single-photon counting system at room temperature.

Supplementary information

Supplementary information is available for this paper at 10.1038/s41467-020-20551-z.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge financial support from the Ministry of Education of Singapore (MOE) under its Tier3 and Tier1 programme (MOE 2016-T3-1-004, R-397-000-274-112, R-397-000-270-114), National Medical Research Council (NMRC/OFIRG/17nov066, R-397-000-317-213), and the National University of Singapore.

Author contributions

Y.Z. conceived and supervised the project. L.R. performed the studies. All authors participated in analyzing the results, preparing the figures, and writing the paper.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

References

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

6.

7.

8.

9.

10.

11.

12.

13.

14.

15.

16.

17.

18.

19.

20.

21.

22.

23.

24.

25.

26.

27.

28.

29.

30.

31.

32.

33.

34.

35.

36.

37.

38.

39.

40.

41.

42.

NIR-excitable heterostructured upconversion perovskite nanodots with improved stability

NIR-excitable heterostructured upconversion perovskite nanodots with improved stability