Complex networks are abundant in nature and many share an important structural property: they contain a few nodes that are abnormally highly connected (hubs). Some of these hubs are called influencers because they couple strongly to the network and play fundamental dynamical and structural roles. Strikingly, despite the abundance of networks with influencers, little is known about their response to stochastic forcing. Here, for oscillatory dynamics on influencer networks, we show that subjecting influencers to an optimal intensity of noise can result in enhanced network synchronization. This new network dynamical effect, which we call coherence resonance in influencer networks, emerges from a synergy between network structure and stochasticity and is highly nonlinear, vanishing when the noise is too weak or too strong. Our results reveal that the influencer backbone can sharply increase the dynamical response in complex systems of coupled oscillators.

Influencer networks include a small set of highly-connected nodes and can reach synchrony only via strong node interaction. Tönjes et al. show that introducing an optimal amount of noise enhances synchronization of such networks, which may be relevant for neuroscience or opinion dynamics applications.

A central discovery in network science is that a small group of highly connected hubs can couple to the network more strongly than their peers and greatly influence the network behavior1–6. Examples of network influencers can be found in neuroscience (e.g., normal and aberrant synaptic connectivity7–10), political opinions (e.g., election blogging11 or social networks), and man-made scale-free networks (e.g., the internet1). Surprisingly, the presence of such influencers makes synchronization of deterministic network dynamics more difficult because networks with influencers require stronger coupling than homogenous networks12,13; indeed, in many situations, synchronization of influencer networks cannot be achieved at all14,15. This observation is all the more remarkable because synchronization plays a fundamental role in regulating network function16,17 and is mediated predominantly through influencers7,18,19. This raises a crucial question: why have many real-world networks evolved to contain influencers when they appear to be detrimental to the network dynamics, at least at face value?

While strong random fluctuations usually have a negative effect in complex systems it has long been recognized that a small amount of noise can actually improve the system response and its ability to process information. Known mechanisms for such a constructive influence of noise are stochastic resonance, coherence resonance and noise induced synchronization20–30. The term coherence resonance is used to describe an optimal response of noise-induced oscillations without external stimmulus in excitable cells22. It was observed in globally coupled systems23, in homogeneous networks24,25, in non-excitable systems near a Hopf bifurcation26 and two coupled oscillators27. The effects of coherence resonance and its role in heterogeneous networks such as influencer networks remains elusive.

In this work, we show that stochastic forcing of influencers can lead to an optimal collective network response. Strikingly, introduction of noise synergizes with the network structure to create collective oscillations that become optimal at a given noise strength in the influencers. This phenomenon emerges in two steps. First, the network acts as a nonlinear filter for the stochastic influencer dynamics, and at an optimal noise strength, the influencers induce synchronization in the nodes directly connected to them. Second, different parts of the network develop macroscopic dynamics and interact indirectly through the influencers. We develop an adiabatic theory to uncover this macroscopic interaction law and show that it mediates the emergence of global collective oscillations. When the noise in the influencers is either too weak or too strong, the coupling vanishes. Interestingly, at a macroscopic level, the interaction between different parts of the network can be described by a hyper-graph.

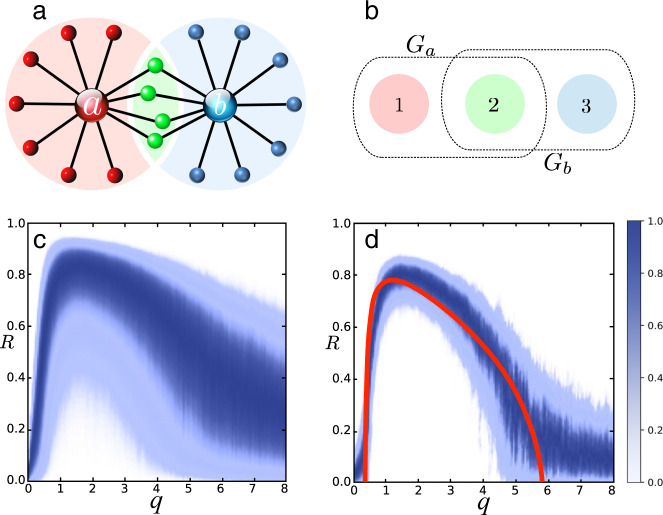

We refer to a network where most nodes couple predominantly to a small number of influencers as an influencer network, and refer to the remaining nodes as followers (Fig. 1). As generic oscillatory dynamics, we consider a network of phase oscillators

Coherence resonance in an influencer network.

Distribution of the order parameter R versus the effective diffusion q in the influencers. a Influencers a and b are hubs that couple strongly to the network, and all other nodes are regarded as followers. Three distinct partitions of followers are shown in red, blue, and green, which connect to influencer a, b, and both a and b, respectively. In our simulation, each partition has 300 followers. b Mean-field theory predicts that the interactions of the partition mean-fields take place in a hyper-graph mediated by the coupling functions Ga and Gb see Methods. c, d For each value of effective noise strength q in the influencers, we plot the density of the global order parameter R on a color scale from 0 (white) to the maximum value (dark blue). At an optimal noise strength, the mean value of the global order parameter reaches a maximum, revealing the coherence resonance effect. In c the dynamical frequency gap between influencers and followers ΔΩ/λ0 = 18 is moderate, whereas in d ΔΩ/λ0 = 198 is large. The solid red line in c is our analytical prediction.

In Methods we show how Eq. (1) can be recast in terms of dimensionless effective parameters shown in Table 1. These effective parameters, and in particular the influencer effective noise strength q = D/ΔΩ, play key roles in the collective dynamics of the system. The dynamical frequency gap ΔΩ/λ0 leads to a time scale separation between the dynamics of the followers and the influencers. A coupling intensity β of comparable but smaller magnitude leads to an effective coupling strength Λ close to one for which the effect of coherence resonance is most pronounced. We note that the dynamical frequency gap needs to be large in units of λ0, but it can be small in natural time units. In Supplementary Note 1, we present an example of the transformation for realistic parameters in Eq. (1) to effective parameters.

| Parameter | Meaning | range |

|---|---|---|

| ΔΩ/λ0 = Δω/λ0 + (β − 1)c0 | dynamical frequency gap | ΔΩ/λ0 ≫ 1 |

| Λ = βλ0/ΔΩ | dimensionless coupling strength | Λ < 1 |

| q = D/ΔΩ | influencer effective noise strength | q = O(1) |

| D0/λ0 | followers effective noise strength | D0/λ0 ≪ 1 |

| γ0/λ0 | followers frequency heterogeneity | γ0/λ0 ≪ 1 |

We divide the followers into partitions Pσ of nodes connected to the same set of influencers. In Fig. 1, we show an influencer network with two influencers (a and b) and three partitions of followers (σ = 1,2,3), which are connected to influencers a, b, or both (see additional examples in Supplementary Note 2). To capture the collective dynamics in each partition σ, we introduce the complex mean-fields

With deterministic influencers where q = 0, and when ∣Λ∣ < 1, the influencers cannot frequency lock to the followers. Synchronization of the followers through the influencer backbone is poor and counteracted by noise and frequency heterogeneity in the followers. Our results show that by setting a weak noise strength or frequency heterogeneity in the followers and by changing the effective noise q in the influencers, synchronization of the whole network increases, reaches a maximum, and then decreases.

We numerically integrate our model Eq. (1) in dimensionless units (Table 1) for the network with two influencers (as shown in Fig. 1) with 300 identical followers in each partition, and a small fixed noise strength in the followers. By changing the noise strength in the influencers, we then obtain the distribution of the order parameter R as a function of q. After a transient, the order parameter is independent of the initial conditions. At an optimal noise strength, R reaches its maximum (in expected value), as shown in Fig. 1 for ΔΩ/λ0 = 18 (panel c) and for ΔΩ/λ0 = 198 (panel d). The solid line is a theoretical prediction in the thermodynamic limit for heterogeneous followers using a slow-fast approximation. Frequency heterogeneity and noise in the followers have qualitatively and quantitatively the same desynchronizing effect. Optimal synchronization of the whole network is predicted theoretically and achieved in all simulations for an effective noise strength q ≈ 1 in the influencers, see details in Methods. Our mean-field analysis predicts that the effect of coherence resonance is only observed for very small frequency heterogeneity or noise in the followers, below a threshold that depends on Λ (Supplementary Note 3).

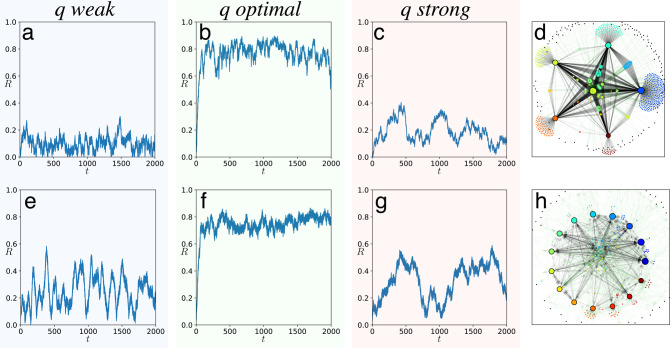

In Fig. 2, we show the time series of the order parameter R for two complex and real-world networks. The upper row represents a scale-free network and the lower row the directed neural network in the model organism Caenorhabditis elegans. We assign the role of influencers to the K most strongly connected nodes and use a weighted connectivity matrix Wnm = 1 for all connections from or to an influencer, and Wnm = 0.01 for all other connections. For small effective noise q in the influencers (Fig. 2, q weak), the order parameter fluctuates at a low level. When q = 1 (q optimal), the order parameter fluctuates around a value close to 1, revealing coherent collective oscillations. Finally, when q is large (q strong), the order parameter decreases again, revealing the loss of synchrony. All parameters for the simulation and numerical scheme can be found in Methods. In Supplementary Note 4, we show three additional examples of coherence resonance in influencer networks; with 3 influencers, a random network with 100 influencers, and a network of linked political blogs.

Coherence resonance of the order parameter in different complex networks.

a–c, e–g The time series of the order parameter R for three values of noise strength in the influencers for weak q = 0.1 (a, e), optimal q = 1 (b, f), and strong q = 10 (c, g). d, h show the corresponding networks with d a scale-free network with exponent 21 and h C. elegans directed neural network3. See Methods for further details. Additional examples can be found in Supplementary Note 5.

Let us consider a single influencer. When its followers are asynchronous, the sinusoidal contributions in the sum of the coupling functions for that influencer average out, and the influencer phase is effectively decoupled from the followers. The influencer is independent of the network and acts as a common stochastic force on the followers connected to it. The additive noise in the influencer enters the dynamics of its followers multiplicatively through the coupling function. That is, the network acts as a nonlinear filter for the noise in the influencers. We can show that the effective diffusion constant of the integrated stochastic forcing in the followers, a proxy for the noise strength, attains a maximum at an optimal effective noise strength

For simplicity, we provide an analysis of the influencer network shown in Fig. 1. Mean-field equations for mixed repulsive and attractive coupling or intra- and inter-partition interactions in the followers can be generalized from these results. In Methods, we show that assuming large partition sizes ∣Pσ∣ ≫ 1, large dynamical frequency gap ΔΩ/λ0 ≫ 1, and noise free followers D0 = 0 with frequency heterogeneity γ0, it is possible to derive averaged dynamics of the partition mean-fields Zσ in an adiabatic approximation. The resulting deterministic equations have the structure of a hyper-network. In our example, the governing equations are

The interaction functions Ga and Gb can be determined analytically; they depend on Λ and q, are maximal at an optimal noise strength, and vanish at critical values of q. That is, at weak or strong noise in the influencers, the hyper-network interactions vanish, revealing the highly nonlinear nature of the phenomenon. In particular, this means that the macroscopic fields will not interact in the strong noise limit. We derive the analytic expressions for the coupling functions Gk(Z; Λ, q) in Methods.

When influencers have equal parameters q and Λ the synchronization manifold Zσ = Z is invariant under (6) and (7) and stable for phase-attractive coupling. Hence, the macroscopic fields synchronize and we can explain the global coherence resonance by restricting the analysis to this invariant subspace. Our mean-field theory predicts both effects: the coherence resonance of the partition order parameters and phase synchronization of the partition mean-fields as shown in Methods. The solid line in Fig. 1 (right) is the stationary average order parameter predicted by our theory in the infinite time-scale separation limit and with frequency heterogeneity γ0/λ0 = 0.02 in the followers. The predicted values agree with simulations of the finite size network, large dynamical frequency gap ΔΩ/λ0 = 198 and identical followers with noise D0/λ0 = 0.02. In Supplementary Information, we provide two short movies displaying synchronization of the network in Fig. 1 at an optimal noise strength in the two influencers.

We have found a new effect induced by a synergy between noise and network structure to generate a transition towards a synchronization that would not be possible in the absence of noise. The key element for this effect is the existence of influencers – a group of hubs that couple strongly and connect different parts of a network. Although deterministic network parameters prevent synchronization, we show that an optimal noise strength in the influencers can induce and mediate synchronization. The mechanism for this coherence resonance in influencer networks is different from the known effect of coherence resonance in homogeneous networks with excitatory dynamics, where noise simply excites oscillations23–25. At the macroscopic level, the interaction between different parts of the network is indirect and takes place on an emerging hyper-network, thus changing the interaction structure from the microscopic level. Such higher order interactions have previously been conjectured and reported in neuronal data recordings37. Our findings suggest that the emergent order in complex systems could be controlled by regulating the noise in only a few key nodes.

To bring the Eq. (1) into a dimensionless form with effective parameters given in Table 1, we change the time scale to units of 1/λ0 and add the frequency shift from the bias c0 in the coupling function to the natural frequencies of the oscillators, i.e., ωn ↦ ωn + λnc0 and

In Table 2, we present the main parameters that naturally appear in the phase model Eq. (1) and give rise to effective parameters, as shown in Table 1 in the main text. The main parameters in our mean-field analysis are shown in Table 3.

| Parameter | Meaning |

|---|---|

| ωn | isolated frequency of the nth oscillator; |

| set as ωn = ω0 + γ0νn for followers and ω for influencers | |

| ω0 | mean frequency of the followers |

| γ0νn | frequency deviation ωn − ω0 of the nth follower |

| γ0 | scale parameter of follower frequency distribution |

| Δω | gap (ω − ω0) between influencer and average follower frequency |

| Wnm | nonnegative matrix of connection weights |

| μn | connection intensity (μn = ∑mWnm) |

| λn | coupling strength of the nth oscillator; |

| λ0 for followers and βλ0 for influencers | |

| β | coupling intensity for influencers |

| Dn | noise strength set as D for influencers and D0 for followers |

| α | phase frustration in the coupling function g |

| c0 | shear parameter in the coupling function g |

| Parameter | Meaning |

|---|---|

| Pσ | follower partitions according to the influencers they connect to |

| Iσ | set of influencers of a partition σ |

| Zσ | complex mean-field of partition σ (order parameter Rσ = ∣Zσ∣) |

| Gk | coupling function between mean-fields mediated by influencer k |

| wkσ | relative size of partition σ among the followers of influencer k |

| F | Ricatti vector field see Eq. (15) |

| hσ, hk | forces on oscillators in partition σ and on influencer k |

| Hσ | average of hσ obtained from adiabatic mean-field approximation |

In our analysis and our simulations, we use the transformed, dimensionless canonical form (8) and (9) of the phase equations (1). Existing connections in the network from and to the influencers are given the weight Wmn = 1 and connections between followers Wnm = 0.01. The followers couple to their neighbors with strength λn = λ0 and influencers with strength λk = βλ0. The phase frustration in the coupling function is set to α = −0.1. The frequency deviations νn of the followers are drawn from a Cauchy distribution p(ν) = 1/π(ν2 + 1) and multiplied by γ0/λ0. Thus, frequency heterogeneity and noise strength in the followers are given by γ0/λ0 and D0/λ0, respectively. We chose βk = β, λk = βλ0 and Dk = D for all influencers, so that ΔΩ/λ0, Λ and q are identical for all influencers. We integrate the Langevin equations of the phases with an Euler-Maruyama scheme and small time steps dt = 5 ⋅ 10−4 because of the large time scale separation ΔΩ/λ0 ≫ 1.

The parameters of Fig. 1 are as follows: The network structure is a pure influencer network without connections between followers or between influencers. We simulate 300 identical followers γ0/λ0 = 0 in each of the three partitions with small independent noise D0/λ0 = 0.02. In the lower left panel we have β = 10, a dynamical frequency gap of ΔΩ/λ0 = 18 and an effective influencer coupling strength Λ = 10/18. In the lower right panel β = 100, ΔΩ/λ0 = 198 and Λ = 100/198. For each value of the effective influencer noise strength q = D/ΔΩ we record a histogram of the order parameter over T = 104 time units, which is much longer than the relaxation time of R. The theoretical prediction, the solid line in the lower right panel, is for noiseless followers D0 = 0 and γ0/λ0 = 0.02.

Parameters of Fig. 2 are as follows: For the C. elegans directed neuronal network3, we choose the top K = 15 out-degree nodes as influencers. All nodes with zero in-degree have been removed, resulting in a network with N = 268 nodes. Connections between followers are given the weight Wnm = 0.01. We simulate identical followers γ0/λ0 = 0 with small independent noise D0/λ0 = 0.02. The dynamical frequency gap between followers and influencers is ΔΩ/λ0 = 18 and the effective coupling strength in the influencers is Λ = 10/18. Shown are three time series of the network order parameter for small (q = 0.1), optimal (q = 1), and large (q = 10) noise strength in the influencers. The undirected scale-free network with exponent 2 is the largest connected component of a network generated via a configurational algorithm1 without self loops or double edges. We chose the top 5 degree nodes as influencers. The other parameters are the same as in the C. elegans neuronal network.

We have developed a mean-field theory for undirected influencer networks with connections exclusively between influencers and followers, as shown in Fig. 1. This theory can be generalized to more complex configurations, heterogenous influencers, directed, attractive, or repulsive coupling between followers and influencers, within partitions or between different partitions. While these generalizations may lead to more complex dynamic behavior, the mechanism for the coherence resonance is apparent in the simplest model.

We consider the network as a union of a set P of followers and a set I of influencers. The nodes n connected to an influencer k are elements n ∈ Pk of the periphery of the influencer k. Intersections of the sets Pk form equivalence classes or partitions Pσ of followers that are connected to the same subsets Iσ of influencers such as in Fig. 1 all followers connected to influencer a or b or to both influencers. The phases of the oscillators are encoded as complex variables

If there is a large dynamical frequency gap ΔΩk/λ0 ≫ 1 between the followers and an influencer, oscillators in the follower group experience an average force from the fast influencer. Conversely, if the followers are desynchronized, the mean-field of the followers vanishes and the influencer phases perform a drift diffusion process on the circle

For ΔΩ/λ0 ≫ 1, the system has slow and fast dynamics and we can replace the influencer phases zk contributing to the force fields hσ(11) in each partition σ by the expected values Gk of zk subject to Langevin equation (14). On the fast time scale of the influencers, the fields hk are changing very slowly and can assumed to be constant for the calculation of the Gk. In this averaged dynamics, the influencers create an average force Hσ that follows the partition mean-fields adiabatically. The slow dynamics of the partition mean-fields is thus given as

The Langevin equation (14) for zk with constant fields hk is indeed a complex formulation of the noisy Adler equation42

If all influencers have the same effective noise strength

Supplementary information is available for this paper at 10.1038/s41467-020-20441-4.

We would like to thank C. Sagastizábal, D. Eroglu, S. van Strien, D. Turaev, J. Lamb, and A. Pikovsky for enlightening discussions. This work was supported in parts by the DFG and FAPESP through the IRTG 1740/TRP 2015/50122-0, by the Center for Research in Mathematics Applied to Industry (FAPESP Cemeai grant 2013/07375-0) and grants 2015/04451-2, by the Royal Society London, CNPq grant 302836/2018-7, and by the Serrapilheira Institute (Grant No. Serra-1709-16124).

R.T. and T.P. wrote the text and developed the theory. R.T. made the slow fast approximation and numerical solutions of the special functions. C.E.F. made simulations of Fig. 1. T.P. and R.T. made the Figures.

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Input files or sets of input parameters for Fortran as well as self-developed Python codes are available from the corresponding author upon request.

Authors declare no competing interests.

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

6.

7.

8.

9.

10.

11.

12.

13.

14.

15.

16.

17.

18.

19.

20.

21.

22.

23.

24.

25.

26.

27.

28.

29.

30.

31.

32.

33.

34.

35.

36.

37.

38.

39.

40.

41.

42.

43.