Whether it be physical, biological or social processes, complex systems exhibit dynamics that are exceedingly difficult to understand or predict from underlying principles. Here we report a striking correspondence between the excitation dynamics of a laser driven gas of Rydberg atoms and the spreading of diseases, which in turn opens up a controllable platform for studying non-equilibrium dynamics on complex networks. The competition between facilitated excitation and spontaneous decay results in sub-exponential growth of the excitation number, which is empirically observed in real epidemics. Based on this we develop a quantitative microscopic susceptible-infected-susceptible model which links the growth and final excitation density to the dynamics of an emergent heterogeneous network and rare active region effects associated to an extended Griffiths phase. This provides physical insights into the nature of non-equilibrium criticality in driven many-body systems and the mechanisms leading to non-universal power-laws in the dynamics of complex systems.

The emergent excitation dynamics of an ultracold gas of Rydberg atoms exhibits features analogous to epidemic spreading on networks. Wintermantel et al. propose a controllable experimental system for studying network dynamics at the interface of mathematical models and real-world complex systems.

The dynamical behavior of an exceptionally diverse spectrum of real-world systems is governed by critical events and phenomena occurring on vastly different spatial and temporal scales. A disease outbreak, for example, can be very sensitive to the type of disease and the behavior of individuals, yet epidemics generically feature a characteristic time dependence1 that emerges from the connections within and between communities2,3. In studying these systems, complex networks provide a crucial layer of abstraction to bridge the behavior of individuals and the macroscopic consequences4. Accordingly, they have found applications not only in biology and the study of epidemics2, but also in informatics5, marketing6, finance7, and traffic flow8. An overarching challenge in these fields is to find general principles governing complex system dynamics and to pinpoint how apparent universal characteristics emerge from the underlying network structure.

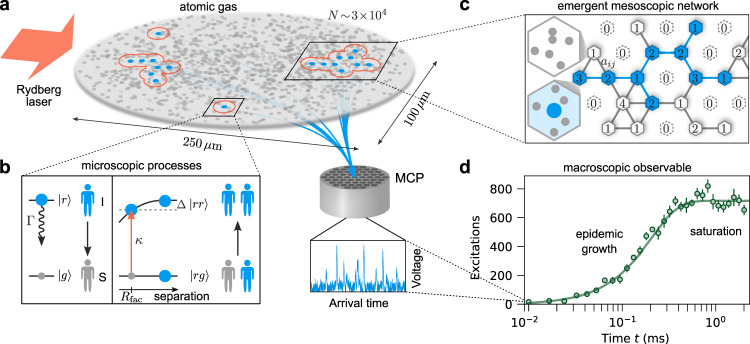

In this work, we address this challenge using a highly controllable complex system that consists of a trapped ultracold atomic gas continuously driven to strongly interacting Rydberg states by an off-resonant laser field (Fig. 1). Our main findings include: first, the rapid growth of excitations driven by a competition between microscopic facilitated excitation and decay processes (playing the role of the transmission of an infection and recovery, respectively). The observed dynamics follow a power-law time dependence that parallels that which is empirically observed in real-world epidemics, providing a powerful demonstration of universality reaching beyond physics. Second, a full description and interpretation of the experiment in terms of an emergent susceptible-infected-susceptible (SIS) network linking the observed macroscopic dynamics to the microscopic physics. Third, the unexpected presence of rare region effects and a dynamical Griffiths phase9–11 associated with the emergent network structure, which gives rise to critical dynamics over an extended parameter regime and explains the appearance of power-law growth and relaxation, but with non-universal exponents.

Physical system for studying epidemic growth and dynamics on complex networks.

a Experiments are performed on a two-dimensional gas containing N ~ 3 × 104 potassium atoms driven by an off-resonant laser field. The gas is initially prepared with a small number of seed excitations (blue disks), which then evolves according to the microscopic processes depicted in sub-figure b, giving rise to growing excitation clusters that spread throughout the system. After different exposure times t, the Rydberg atoms are field ionized and detected on a microchannel plate detector (MCP), where the incident ions create voltage spikes (blue trace). b Each atom can be treated as a two-level system with a ground state (gray disks) and excited Rydberg state

The microscopic processes governing the dynamics of ultracold atoms driven to Rydberg states by an off-resonant laser field, shown in Fig. 1a, b, bear close similarities to those in epidemics12. Each atom can be considered as a two-level system consisting of the atomic ground state (gray disks, healthy) and an excited Rydberg state (blue disks, infected). An excited atom can spontaneously decay (recovery, with rate Γ), or it can facilitate the excitation of other atoms (transmission of the infection, with rate κ) that satisfy certain constraints linked to their positions and velocities. This results in rapid spreading of the excitations through the gas (depicted by growing excitation clusters in Fig. 1a)13–17.

Our experimental studies start from an ultracold thermal gas of 3 × 104 potassium-39 atoms in their ground state

To exemplify the analogy to epidemics, in Fig. 1d we present data for κ = 10 kHz showing different stages of the dynamics. Immediately following the seed excitation pulse we observe a period of very fast growth of the Rydberg excitation number, that is, within the Rydberg state lifetime the excitation number increases from its initial value to more than 400, corresponding to more than five doublings in 0.19 ms. At around t ≈ 0.5 ms, after the initial growth stage, the system saturates with a high constant excitation number (i.e., an endemic state). However, the saturation value is still significantly lower than the estimated maximum number of excitations that can fit in the system ≳2000 assuming an inter-Rydberg spacing of ~Rfac. On even longer timescales than those studied here (≳10 ms), the system should eventually relax back to an absorbing or self-organized critical state due to the gradual depletion of particles23,26.

The growth phase of many real epidemics is observed to follow a characteristic power-law dependence described by the phenomenological generalized-growth model (GGM)1,

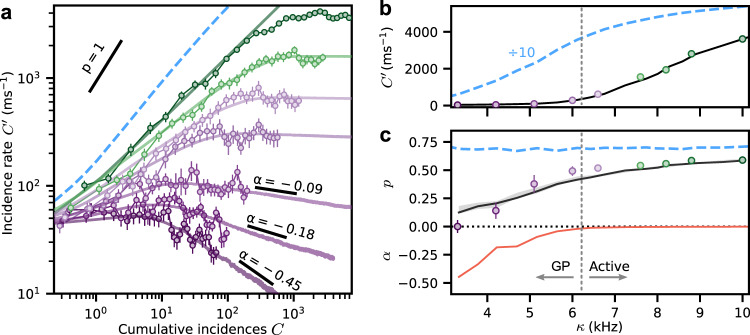

In Fig. 2a we represent the data from Fig. 1d in terms of

Rydberg excitation incidence curves for different facilitation rates showing power-law growth and Griffiths effects.

a Incidence rate

To explain the experimental observations we develop a physically motivated SIS network model. We assume that the two-dimensional gas can be subdivided into cells that represent nodes of a network (Fig. 1c). Each cell i can either be in a susceptible state (absence of Rydberg excitation, Ii = 0) or infected (one Rydberg excitation, Ii = 1), and contains a certain number of particles Ni that can be excited. Vacant cells with Ni = 0 (and hence also Ii = 0) translate to unconnected, missing nodes. The probability for a given node i to become infected is described by the following stochastic master equation2

To define the adjacency matrix entries aij we coarse grain our system into hexagonal cells (each with area

To numerically simulate this model we solve Eq. (2) using a Monte-Carlo approach30. In each time step we compute the transition rate for each node Ri = κNi(1 − Ii)∑jaijIj + ΓIi. One node m is then picked at random according to the weights Ri and its state is flipped Im → 1 − Im. The timestep is computed according to

The numerical simulations, shown as solid curves in Figs. 1d and 2, are in excellent agreement with the experimental observations. Importantly, they fully reproduce the fast power-law growth with p < 0.6, the different plateau heights, and even the late-time relaxation as a function of κ. The only free parameter in the model is ϵ(κ) which is adjusted for each curve and is found to be a monotonically increasing function of κ with 0.02 < ϵ(κ) < 0.1 over the explored parameter range. This parameter directly controls the network structure, that is, for κ = 10 kHz the network consists of M ≈ 2300 nodes with Ni > 0 and the local si follow approximately Poissonian distributions with 〈si〉 = var(si) ≤ 5.3 (maximal at trap center) while for κ = 3.3 kHz, M ≈ 660, and 〈si〉 = var(si) ≤ 1.3 (see Supplementary Note 2). For comparison, the dashed blue lines in Fig. 2 show comparable simulations with Ni = μi, that is, corresponding to a locally homogeneous network with the same average node degree. These homogeneous network simulations show faster initial growth, constant p values ≈ 0.7, higher plateaus saturating at the system size limit, and a dramatic shift of the critical point to lower κ values, which are inconsistent with the experimental data. The good agreement between experiment and heterogeneous network simulations demonstrates that the emergent macroscopic dynamics of the system crucially depend on the weighted node degree distributions and heterogeneity controlled by the atomic density and the parameter ϵ(κ).

The heterogeneous spatial network model described by Eq. (2) provides an accurate and computationally efficient coarse-grained description of the physical system and its dynamics involving just a few microscopically controlled parameters. The importance of heterogeneity is particularly surprising since atomic motion could be expected to quickly wash out the effects of spatial disorder (the characteristic thermal velocity corresponding to the gas temperature at 20 μK is vth = 65 μm/ms ≈3.5Rfac/τ). Our findings can be explained by assuming that the facilitation constraint depends on both the relative positions and velocities of the atoms. Taking into account the Landau–Zener transition probability for moving atoms confirms that only atom pairs with small relative velocities vLZ ≲ 1 μm/ms contribute to the spreading of facilitated excitations22. This provides a qualitative explanation for the inferred ϵ(κ) ≪ 1 and its approximate κ dependence (due to the intensity dependence of vLZ) (see Methods section). It also sets the timescale for diffusion in phase space longer than the duration of our observations ≳ 2 ms. Thus, spatial constraints and (effectively static) heterogeneity can be understood as properties of an emergent network structure that is dynamically formed while the laser coupling is on (see also ref. 31 for a related interpretation of excitation dynamics on smaller preformed emergent lattices).

Spatial disorder is known to play a very important role in condensed matter systems, giving rise to new many-body phases, localization effects, and glassy behavior32. There is still much to be explored concerning analogous effects of disorder and heterogeneity on non-equilibrium processes on networks. One key theoretical finding however is the emergence of an exotic Griffiths phase9–11, expected to replace the singular critical point between the subcritical and active phase by an extended critical phase. The dynamics in the Griffiths phase can be understood in terms of the dynamics of rare supercritical clusters (κNi ≳ Γ for all sites i of the cluster), surrounded by subcritical regions. For a Poissonian degree distribution the probability for a seed to land on a supercritical cluster of Mclust nodes is

Such Griffiths effects provide a natural explanation for several of our experimental observations. First of all, the relatively short time for each curve to reach the plateau and the strong κ dependence of the plateau heights are compatible with the presence of rare regions with an above-average infection rate that span only a fraction of the entire system, controlled by the disorder strength entering via ϵ(κ). This also explains the sizable shift of the critical point between subcritical (

This work highlights a controllable physical platform for experimental network science situated at the interface between simplified numerical models and empirical observations of real-world complex dynamical phenomena. Ultracold atoms provide the means to introduce and control different types of reaction-diffusion processes as studied here, but also to realize different types of spatial networks by structuring the trapping fields33 and to access the full spatio-temporal evolution of the system29. This would allow for in-depth investigations of the phase structure and critical properties with varying disorder strength and different network geometries. Our discovery that the growth dynamics of a driven-dissipative atomic gas is described by an emergent heterogeneous network that is relatively robust to particle motion suggests that similar effects could also be observable in noisy room temperature environments16,26. Thus, heterogeneous network dynamics and Griffiths effects may arise naturally in very different non-equilibrium systems, having important implications, for example, in understanding non-equilibrium criticality without fine tuning23,26,34 and for finding effective strategies for controlling dynamics on complex networks35. Future experiments could also investigate the quantum contact process12,36–38 and quantum analogs of the Griffiths phase on heterogeneous networks39.

The experimental procedure to observe Rydberg excitation growth consists of three main steps, during which we keep the optical trap on. Initially a small number of seed excitations are prepared at random positions in the gas. For this we keep the laser frequency fixed at Δ = −30 MHz below the zero-field resonance and briefly applying an electric field of 0.28 V/cm for 4 μs, exploiting the DC Stark effect to tune the atoms into resonance. The laser is then momentarily switched off for 6 μs to ensure the electric field is fully off before starting the off-resonant driving. Next we apply the off-resonant laser field which causes rapid growth of the number of excitations in the gas. We calibrate the single-atom facilitation rate κ against a measurement of the initial growth rate r = 27(8) kHz, measured for high intensity and very short times t ≪ τ where many-body effects can be safely neglected. This is then divided by an estimate of the (cloud averaged) mean number of particles that meet the facilitation condition

To extract both the growth and relaxation parameters from these data, we extend the GGM to allow for different exponents in the growth and relaxation phases

By comparing the SIS network simulations to the data, we infer that the fraction of atoms that participate in the excitation dynamics is relatively small. This is quantified by the fitted ϵ(κ) values that vary between 0.023 and 0.094 (for κ = 3.3 kHz and κ = 10 kHz, respectively). These small values of ϵ and the approximate κ dependence can be explained by the velocity dependence of the Landau–Zener transition probability, which restricts facilitation to atoms with small relative velocities v ≲ vLZ ≪ vth (for a related calculations see Appendix E in ref. 22). The Landau–Zener velocity can be expressed as

For realistic experimental parameters Rfac = 3.5 μm,

Supplementary information is available for this paper at 10.1038/s41467-020-20333-7.

We acknowledge valuable discussions with Cédric Sueur. This work is supported by the “Investissements d’Avenir” program through the Excellence Initiative of the University of Strasbourg (IdEx), the University of Strasbourg Institute for Advanced Study (USIAS), and is part of and supported by the DFG SPP 1929 GiRyd and the DFG Collaborative Research Center “SFB 1225 (ISOQUANT).” T.M.W., S.S., and M.M. acknowledge the French National Research Agency (ANR) through the Programme d’Investissement d’Avenir under contract ANR-17-EURE-0024. M.M. acknowledges QUSTEC funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation program under the Marie Skłdowska-Curie Grant Agreement No. 847471. S.D. acknowledges support by the European Research Council (ERC) under the Horizon 2020 research and innovation program, Grant Agreement No. 647434 (DOQS).

T.M.W. and S.W. devised and performed the experiments and analyzed the data. T.M.W., M.B., S.D., and S.W. contributed to the theoretical understanding. S.S., M.M., Y.W., and G.L. made contributions to the experimental setup. All authors contributed to interpreting the results and writing of the manuscript.

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

The code to produce the simulation data that support the findings of this study is available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

The authors declare no competing interests.

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

6.

7.

8.

9.

10.

11.

12.

13.

14.

15.

16.

17.

18.

19.

20.

21.

22.

23.

24.

25.

26.

27.

28.

29.

30.

31.

32.

33.

34.

35.

36.

37.

38.

39.

40.