- Altmetric

Living and non-living active matter consumes energy at the microscopic scale to drive emergent, macroscopic behavior including traveling waves and coherent oscillations. Recent work has characterized non-equilibrium systems by their total energy dissipation, but little has been said about how dissipation manifests in distinct spatiotemporal patterns. We introduce a measure of irreversibility we term the entropy production factor to quantify how time reversal symmetry is broken in field theories across scales. We use this scalar, dimensionless function to characterize a dynamical phase transition in simulations of the Brusselator, a prototypical biochemically motivated non-linear oscillator. We measure the total energetic cost of establishing synchronized biochemical oscillations while simultaneously quantifying the distribution of irreversibility across spatiotemporal frequencies.

The degree of irreversibility of a dynamical system is commonly characterized by the total rate of entropy production. Seara et al. introduce a measure that quantifies irreversibility from data in broad classes of spatiotemporal non-equilibrium systems.

Introduction

In many-body systems, collective behavior that breaks time-reversal symmetry can emerge due to the consumption of energy by the individual constituents1–3. In biological, engineered, and other naturally out of equilibrium processes, entropy must be produced so as to bias the system in a forward direction4–9. This microscopic breaking of time reversal symmetry can manifest at different length and time scales in different ways. For example, bulk order parameters in complex reactions can switch from exhibiting incoherent, disordered behavior to stable static patterns10,11 or traveling waves of excitation12,13 that break time reversal symmetry in both time and space simply by altering the strength of the microscopic driving force. Recent advances in stochastic thermodynamics have highlighted entropy production as a quantity to measure a system’s distance from equilibrium14–19. While much work has been done investigating the critical behavior of entropy production at continuous and discontinuous phase transitions20–28, dynamical phase transitions in spatially extended systems have only recently been investigated, and to date no non-analytic behavior in the entropy production has been observed29,30.

To address this, we introduce what we term the entropy production factor (EPF), a dimensionless function of frequency and wavevector that measures time reversal symmetry breaking in a system’s spatial and temporal dynamics. The EPF is a strictly non-negative quantity that is identically zero at equilibrium, quantifying how far individual modes are from equilibrium. Integrating the EPF produces a lower bound on the entropy production rate (EPR) of a system. We illustrate how to calculate the EPF directly from data using the analytically tractable example of Gaussian fields obeying partly relaxational dynamics supplemented with out of equilibrium coupling31. We then turn to the Brusselator reaction-diffusion model for spatiotemporal biochemical oscillations to study the connections between pattern formation and irreversibility. As the Brusselator undergoes a Hopf bifurcation far from equilibrium, its behavior transitions from incoherent and localized to coordinated and system-spanning oscillations in a discontinuous transition. The EPF quantifies the shift in irreversibility from high to low wave-number as this transition occurs, but the EPR is indistinguishable from that of the well-mixed Brusselator where synchronization cannot occur. Importantly, the EPF can be calculated in any number of spatial dimensions, making it broadly applicable to a wide variety of data types, from particle tracking to 3+1 dimensional microscopy time series.

Results

Entropy production factor derivation

Consider a system described by a set of M real, random variables obeying some possibly unknown dynamics. A specific trajectory of the system over a total time T is given by X = {Xi(t)∣t ∈ [0, T]}. Given an ensemble of stationary trajectories, the average EPR, , is bounded by5,6,32

We further bound the irreversibility itself by assuming the paths obey a Gaussian distribution. Writing the Fourier transform of Xi(t) as xi(ω), where ω is the temporal frequency, and writing the column vector

This defines the EPF,

As mentioned above, P[x(ω)] describes the dynamics of a non-equilibrium steady state, and no reversal of external protocol is assumed. Further, in writing an expression for

The Gaussian assumption we make here makes Eq. (3) exact only for systems obeying linear dynamics. Nevertheless,

This formulation extends naturally to random fields. For M random fields in d spatial dimensions,

Even without an explicit, analytic expression for the structure factor, C, we can estimate

To illustrate the information contained in

Driven Gaussian fields

Consider two fields obeying Model A dynamics31 with non-equilibrium driving parametrized by α:

The EPR density,

We see that

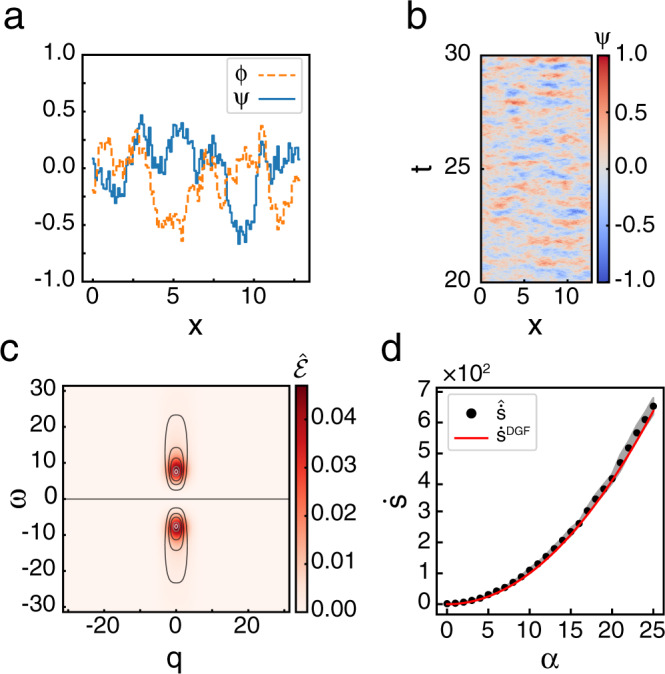

We perform simulations to assess how well

Entropy production rate and entropy production factor are well estimated for driven Gaussian fields.

a Snapshot of typical configurations of both fields, ψ (blue solid line) and ϕ (orange dashed line) obeying Eq. (5) for α = 7.5. b Subsection of a typical trajectory for one field for α = 7.5 in dimensionless units. Colors indicate the value of the field at each point in spacetime. c

Our estimator gives exact results for the driven Gaussian fields because the true path probability functional for these fields is Gaussian. In contrast, the complex patterns seen in nature arise from systems obeying highly non-linear dynamics. For such dynamics, our Gaussian approximation is no longer exact but provides a lower bound on the total irreversibility. To investigate how irreversibility correlates with pattern formation, we study simulations of the Brusselator model for biochemical oscillations35. We begin by describing the various dynamical phases of the equations of motion. Next, we calculate

Reaction-diffusion Brusselator

We use a reversible Brusselator model30,35–37 with dynamics governed by the reaction equations:

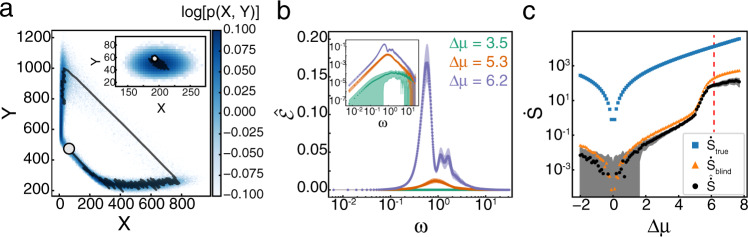

a Typical trajectory in (X, Y) space for Δμ = 6.2. The occupation probability distribution is shown in blue, with a subsection of a typical trajectory shown in black. The end of the trajectory is marked by the white circle. Inset shows the same information for the system at equilibrium, where Δμ = 0, with the same colorbar as the main figure. b

As Δμ increases, the macroscopic version of Eq. (8) undergoes dynamical phase transitions. For all Δμ, there exists a steady state (Xss, Yss), the stability of which is determined by the relaxation matrix, R [Supplementary Note 7]. The two eigenvalues of R, λ±, divide the steady state into four classes33:

The eigenvalues undergo these changes as Δμ changes, allowing us to consider Δμ as a bifurcation parameter. We define ΔμHB as the value of Δμ where the macroscopic system undergoes the Hopf bifurcation.

Non-equilibrium steady states are traditionally characterized by their circulation in a phase space39–43. One may then question how it is possible to detect non-equilibrium effects in the Brusselator when the system’s steady state is a stable attractor with no oscillatory component. While this is true for the macroscopic dynamics used to derive λ±, we simulate a system with finite numbers of molecules subject to fluctuations. These stochastic fluctuations give rise to circulating dynamics, even when the deterministic dynamics do not36. We see persistent circulation in the (X, Y) plane when

In order to assess the accuracy of our estimated EPR,

In order to account for this, we recalculate

To further benchmark our estimator, we calculate

Prior to ΔμHB, both

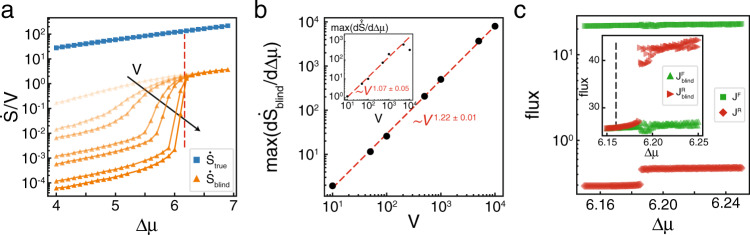

Finite size scaling of

a

The Hopf bifurcation for the Brusselator is supercritical23, meaning the limit cycle grows continuously from the fixed point when Δμ − ΔμHB ≪ 1. Further from the transition point, the trajectory makes a discontinuous transition. At our resolution in Δμ, this discontinuous transition is what underlies the shift in

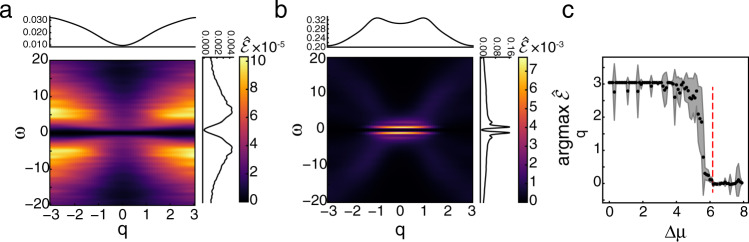

One gains further insight into the dynamics through the transition by studying

To investigate how dynamical phase transitions manifest in the irreversibility of spatially extended systems, we simulate a reaction-diffusion Brusselator on a one-dimensional periodic lattice with L compartments, each with volume V, spaced a distance h apart. The full set of reactions are now

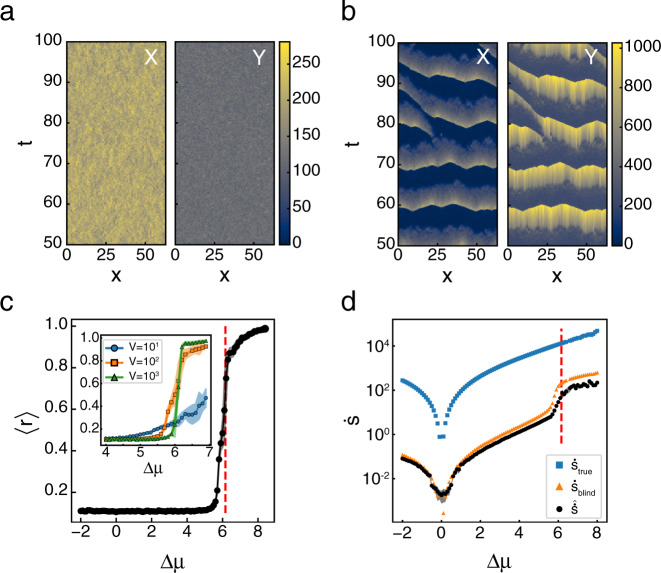

In the steady state, the reaction-diffusion Brusselator has the same dynamics as the well mixed Brusselator, and so it is not surprising that it’s EPR curve as a function of Δμ is similar (Supplementary Fig. 6). However, unlike the well-mixed system, the Hopf bifurcation signals the onset of qualitatively distinct dynamics in the reaction-diffusion system. Prior to the Hopf bifurcation, there are no coherent, spatial patterns in the system’s dynamics (Fig. 4a). Above the Hopf bifurcation, system-spanning waves begin to emerge that synchronize the oscillations across the system (Fig. 4b). Following standard methods50,51, we define the synchronization order parameter, 0 ≤ r < 1, using

Reaction-diffusion Brusselator synchronizes above Hopf bifurcation.

a Subsection of a typical trajectory for X(x, t) and Y(x, t) for a Δμ = 3.5, below the Hopf Bifurcation and b Δμ = 6.2, above it. Color indicates the local number of the chemical species. c Synchronization order parameter, 〈r〉, as a function of Δμ. Vertical red dashed line indicates ΔμHB. Inset shows the same measurement for volumes V = {101, 102, 103} shown by blue circles, orange squares, and green triangles, respectively, at each lattice site over a smaller region of Δμ. Dots and shaded areas show mean ± s.d. of N = 10 simulations. d

Below ΔμHB, r is low and rapidly approaches one as the system approaches the macroscopic bifurcation point (Fig. 4c). Like

Entropy production factor and macroscopic dynamics.

a

Discussion

Previous work has investigated the behavior of

Here, we illustrated that the total irreversibility rate cannot distinguish between the dynamical phase transitions in the well-mixed and the spatially extended Brusselator (Supplementary Fig. 6). While the EPR quantifies the emergence of oscillations, the synchronization of the oscillations across space is only captured in

In summary, we have introduced the entropy production factor,

In active matter, both living and non-living, the non-equilibrium dissipation of energy manifests in both time and space. With the method introduced here, compatible with widely-used computational and experimental tools, we provide access to these underexplored modes of irreversibility that drive complex spatiotemporal dynamics.

Methods

Calculating E

Estimate

The periodogram, is known to exhibit a systematic bias and considerable variance in estimating the true CSD. Both of these issues can be resolved by smoothing

Once

Bias in E ^ S ˙ ^

Our estimates of

Simulation details

To simulate the driven Gaussian fields, Eq. (5), we nondimensionalize the system of equations using a time scale τ = (Dr)−1 and length scale λ = r−1/2. We use an Euler–Maruyama algorithm to simulate the dynamics of the two fields on a periodic, one-dimensional lattice.

We simulate Eq. (8) using Gillespie’s algorithm59 to create a stochastic trajectory through the (X, Y) phase plane with a well-mixed volume of V = 100. We calculate the true

To simulate the reaction-diffusion Brusselator, Eq. (10), we take a compartment-based approach60 where we treat each chemical species in each compartment as a separate species, and treat diffusion events as additional chemical reaction pathways. We nondimensionalize time by

See Supplementary Tables 1–5 for all simulation parameters used in each figure.

Synchronization order parameter

The synchronization order parameter given in Eq. (11), r, is a function of the oscillator phase at every lattice site j at time t, θj(t). In order to calculate θ from our data, we measure the oscillator’s phase with respect to a trajectory’s mean position over time, namely

Supplementary information

Supplementary information is available for this paper at 10.1038/s41467-020-20281-2.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Samuel J. Bryant, Pranav Kantroo, Maria P. Kochugaeva, Rui Ma, Pierre Ronceray, A. Pasha Tabatabai, John D. Treado, Artur Wachtel, Dong Wang, and Vikrant Yadav for insightful discussions. D.S.S. acknowledges support from NSF Fellowship grant #DGE1122492. B.B.M. acknowledges a Simons Investigator award in MMLS and NIH R35 GM138341. M.P.M. and D.S.S. acknowledge support from Yale University Startup Funds. M.P.M. acknowledges funding from ARO MURI W911NF-14-1-0403, NIH RO1 GM126256, Human Frontiers Science Program (HFSP) grant # RGY0073/2018, and NIH U54 CA209992. Any opinion, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the NSF, NIH, HFSP, or Simons Foundation.

Author contributions

D.S.S., B.B.M., and M.P.M. conceived the work. D.S.S. wrote and analyzed simulations. All authors contributed to the interpretation of the data and the preparation of the manuscript.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request.

Code availability

The code used to calculate the EPR and EPF from data, as well as run all the simulations in this study, can be found at https://github.com/lab-of-living-matter/freqent.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

References

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

6.

7.

8.

9.

10.

11.

12.

13.

14.

15.

16.

17.

18.

19.

20.

21.

22.

23.

24.

25.

26.

27.

28.

29.

30.

31.

32.

33.

34.

35.

36.

37.

38.

39.

40.

41.

42.

43.

44.

45.

46.

47.

48.

49.

50.

51.

52.

53.

54.

55.

56.

57.

58.

59.

60.

Irreversibility in dynamical phases and transitions

Irreversibility in dynamical phases and transitions