Electron and hole spins in organic light-emitting diodes constitute prototypical two-level systems for the exploration of the ultrastrong-drive regime of light-matter interactions. Floquet solutions to the time-dependent Hamiltonian of pairs of electron and hole spins reveal that, under non-perturbative resonant drive, when spin-Rabi frequencies become comparable to the Larmor frequencies, hybrid light-matter states emerge that enable dipole-forbidden multi-quantum transitions at integer and fractional g-factors. To probe these phenomena experimentally, we develop an electrically detected magnetic-resonance experiment supporting oscillating driving fields comparable in amplitude to the static field defining the Zeeman splitting; and an organic semiconductor characterized by minimal local hyperfine fields allowing the non-perturbative light-matter interactions to be resolved. The experimental confirmation of the predicted Floquet states under strong-drive conditions demonstrates the presence of hybrid light-matter spin excitations at room temperature. These dressed states are insensitive to power broadening, display Bloch-Siegert-like shifts, and are suggestive of long spin coherence times, implying potential applicability for quantum sensing.

Organic semiconductors employed in light-emitting diodes (OLEDs) allow for magnetic resonance studies that explore light-matter interactions in the ultrastrong-drive regime, where the Rabi frequency exceeds the Larmor frequency. The authors report the formation of Floquet spin states in OLEDs.

A spin in a magnetic field is a perfect discrete-level quantum system, for which resonant electromagnetic radiation can drive coherent propagation in a well-controlled perturbative fashion following Rabi’s theory1. Such propagation is used for magnetic resonance applications in spectroscopy and imaging, where the thermal-equilibrium population of spin states is altered under resonance, inducing an effective magnetization change of nuclear or electronic spins2. Experiments are generally performed under the condition that the Zeeman splitting between spin states induced by a static magnetic field is much larger in energy, or frequency, than the Rabi frequency1. This weak-drive limit of resonant pumping is described by perturbation theory. Magnetic resonance can also be probed by observables secondary to magnetization, such as the permutation symmetry of pairs of spins of electronic excitations. Such spin-dependent transitions are reflected in luminescence or conductivity in atomic, molecular, or solid-state systems3,4 in optically or electrically detected magnetic resonance (ODMR, EDMR) spectroscopies5. Color centers in crystals, like atomic vacancies in silicon carbide or diamond, are widely used in ODMR-based quantum metrology and quantum-information processing6, but are limited in one regard: as dipolar and exchange coupling in the spin pair is strong, substantial level splitting arises at zero external field, posing a lower limit on resonance frequency. Such a limitation does not exist for weakly coupled spin-½ charge-carrier pairs which form, for example, by electron transfer in molecular donor-acceptor complexes, where they account for a range of magnetic-field effects7.

A particularly versatile way to study weakly coupled spin-½ pairs is offered by organic light-emitting diodes (OLEDs), which generate light from the recombination of electrically injected electrons and holes that bind in pairs of singlet or triplet permutation symmetry8. As the formation rates of intramolecular excitons from intermolecular electron-hole carrier pairs differ for singlet and triplet spin permutations, and singlet pairs tend to have shorter lifetimes than triplets, an increase of singlet content in the electron-hole pair depletes the reservoir of available carriers and leads directly to a change in conductivity9–11. Because carrier spins interact with local hyperfine fields, which originate from unresolved hyperfine coupling between charge-carrier spins and the nuclear spins of the ubiquitous protons12, carrier migration through the active OLED layer gives rise to spin precession and, ultimately, mixing of singlet and triplet carrier-pair configurations. As a result, OLEDs can exhibit magnetoresistance on nanotesla scales at room temperature5. A static magnetic field tends to partially suppress this hyperfine spin mixing, an effect that is reversed under magnetic resonance conditions, which give rise to distinct resonances in the magnetoresistance functionality13.

It is important to stress that such studies are only possible in materials characterized by very weak spin-orbit coupling14, such as organic semiconductors, and are not generic to electron-hole recombination in LEDs as a whole. In an inorganic LED, for example, spin mixing occurs by spin-orbit coupling in addition to the fact that recombination does usually not occur into tightly bound, and hence thermally stable, excitonic species. Light generation in inorganic LEDs, in contrast to OLEDs, is therefore primarily not spin dependent. As such, the subsequent discussion strictly only applies to OLEDs comprising materials of weak spin-orbit coupling, i.e., of low atomic-order number. The appeal of experimenting with spins in OLEDs is that their coherence time, i.e., the transverse spin-relaxation time T2, is only weakly dependent on temperature15. This independence is a direct consequence of the lack of spin-orbit coupling, which leaves the carrier dynamics in the local hyperfine fields as the coherence-limiting effect15.

In principle, magnetic resonances can be resolved down to very small frequencies of a few megahertz, limited only by the overall strength of the hyperfine interaction5,16. One advantage of EDMR in OLEDs over conventional EPR in radical-pair-based spin-½ systems17 is that the sample volume can be made almost arbitrarily small. It is therefore possible to achieve high levels of homogeneity both in terms of the static field B0, which defines the Zeeman splitting, and the amplitude of the resonant driving field, B1, whereas at the same time penetrating the non-perturbative regime of ultrastrong drive where B1 becomes comparable to B0, so that the Rabi frequency approaches the Larmor frequency18. Such an ultrastrong-drive regime is of great interest in contemporary condensed-matter physics, although embodiments thereof have proven very challenging to find19,20 and mostly arise in the form of ultrastrong coupling of two-level systems in resonant optical cavities21–23.

The breakdown of the perturbative regime of OLED EDMR has previously been identified under drive conditions of , where conventional power broadening gives way to a variety of strong-drive effects24. Once the driving-field strength exceeds the inhomogeneous broadening of the individual spins of the pair induced by the hyperfine fields, the spins become indistinguishable with respect to the radiation and a new set of spin-pair eigenstates is formed25. The resonant field locks the spin pairs into the triplet configuration, in analogy to the formation of a subradiant state in Dicke’s description of electromagnetic coupling of non-interacting two-level systems26,27. The spin-Dicke state manifests itself in EDMR by the appearance of a particular inverted resonance feature25,28. Experimentally, it is challenging to access this regime of strong and ultrastrong drive for the simple reason that very high oscillating magnetic field strengths have to be generated in close proximity to the OLED. Using either coils24 or a monolithic microwire integrated in the OLED structure18, we were previously able to probe the strong-drive regime of up to

To date, there has been no formulation of the theoretical expectation of the nature of spin-dependent transitions of two weakly coupled spin-½ carriers, electron and hole, under ultrastrong resonant drive. Although a Floquet formalism to treat this problem has been put forward previously, this was only pursued in the weak-drive limit29.

In this work, we begin by setting out a strategy for computing such transitions in the ultrastrong-drive regime using the periodic time-dependent spin Hamiltonian in the Floquet formalism. The numerically rather detailed calculations can be condensed into a diagrammatic representation of the resulting hybrid light-matter states, the spin states of the OLED dressed by the driving electromagnetic field. This approach gives us a complete computation of the EDMR magnetic resonance spectrum of an OLED under the condition of ultrastrong drive, with B1 exceeding B0. With substantial experimental improvements both in terms of the material used and with regard to the monolithic OLED-microwire structure we succeed in experimentally identifying the main predicted Floquet spin states of the OLED under ultrastrong drive conditions. These states are manifested as magnetic-dipole-forbidden multiple-quantum transitions and resonances at fractional g-factors.

Theoretical treatment of the spin dynamics in a strongly driven electron-hole pair beyond the perturbative regime is extremely challenging and has not been considered in detail previously. We approach this problem using quantum-mechanical Floquet theory30. The electron-hole spin-pair Hamiltonian, H(t), is time dependent owing to the presence of a time-dependent (sinusoidal) driving field. Besides the drive, we incorporate in H(t) the electron and hole spin coupling to the external field B0 and the effective local internal hyperfine fields, as well as the isotropic exchange and dipolar interactions between the electron and hole spins. Note that, given the exceedingly weak spin-orbit coupling of the organic semiconductor material used in the experiments discussed in the following, the spin Hamiltonian is perfectly defined without an explicit spin-orbit term, using effective Landé g-factors instead. We direct the interested reader to a recent joint experimental and theoretical examination of the influence of spin-orbit coupling in these materials14. Although all these interactions are time independent, the local hyperfine fields and the dipolar interaction are taken to be random and different for different configurations. Further details of the statistical distribution of spin pairs and the numerical approach to account for this are discussed in Supplementary Notes 1.5 and 1.6.

The time-periodic character of the driving field allows us to write the Fourier decomposition of the Hamiltonian as

The Floquet approach takes advantage of the fact that HF is time independent and Hermitian, thus possessing stationary eigenvectors,

The spin-density matrix of an ensemble of spin pairs, ρ, satisfies the stochastic Liouville equation and is used to compute the steady-state singlet content of the spin pair, i.e., the observable responsible for the experimentally measured conductivity of the OLED. Ultimately, this observable can be expressed by the trace of the steady-state spin-density matrix,

Equation (3) is derived perturbatively, to leading order in the small difference of singlet and triplet recombination rates kr. Note that

The steady-state device current measured in an experiment is a function of the static and oscillating magnetic fields, which give rise to a change

We utilize Eqs. (3) and (4) for the numerical calculation of the EDMR signal

In order to build up an intuitive understanding of the resonant transitions of the electron-hole spin pair emerging under strong and ultrastrong resonance drive and to differentiate the Floquet states responsible for the specific transitions, we develop a diagrammatic representation31 of the dressed states

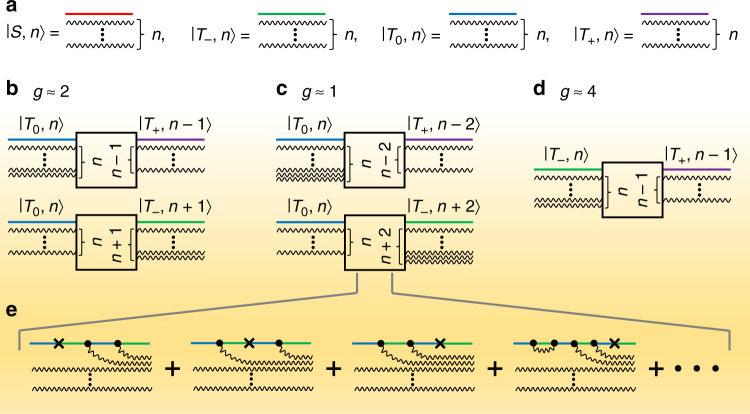

Multiple-quantum transitions of spin pairs in the singlet-triplet basis.

a The Floquet states describing the conductivity of an OLED under magnetic-resonant excitation are defined by the photon number n (illustrated as wavy lines before and after the interaction) and the spin wavefunction (red, green, blue, purple). b The spin-½ resonance of the pair at an effective g-factor of g ≈ 2 corresponds to a raising or lowering of n. c, d Resonances also arise at g ≈ 1 and g ≈ 4 owing to two-photon and half-field transitions, respectively. e Examples of diagrams of the two-photon transitions, where the vortices indicate the creation or annihilation of a photon (•) or spin scattering not involving a photon (×), e.g., owing to hyperfine or dipolar coupling. An infinite number of higher-order loops exists. Magnetoresistance on resonance is calculated by summation over all transitions.

Even though multi-photon transitions in two-level spin systems have been discussed in the context of electron-spin resonance spectroscopy32–34, these are not analogous to two-photon absorption of electric-dipole transitions. As each photon carries angular momentum

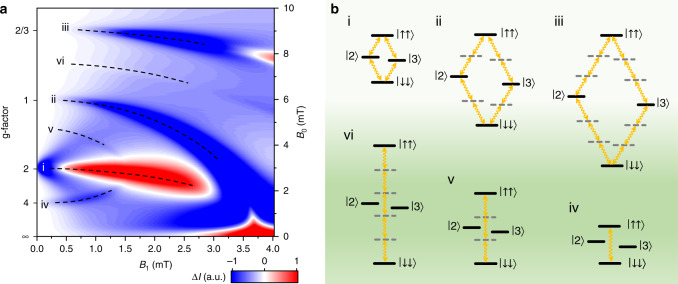

In Fig. 2a the calculated change of spin-dependent current

Floquet spin states in OLED magnetoresistance.

a Calculated change of spin-dependent recombination current as a function of static field B0 and oscillating field B1 for a frequency of 85 MHz. b Term diagrams of integer and fractional g-factor multi-photon transitions. (i–iii)

Identifying these Floquet states experimentally in the spin-dependent transitions that control the magnetoresistance of OLEDs poses two challenges. First, the effective hyperfine fields must be sufficiently small, such that the different resonances do not overlap spectrally. Hyperfine coupling broadens the resonant magnetic-dipole transition inhomogeneously, making individual microscopic spins distinguishable in terms of their resonance energy. This disorder determines the threshold field for the onset of spin collectivity24, when each individual spin becomes indistinguishable with respect to the driving field. Previous studies of the condition of strong magnetic-resonant drive of OLEDs employed either conventional hydrogenated organic semiconductors18,24, or partially deuterated materials with reduced hyperfine coupling strengths24. To maximize the resolution of the experiment, we synthesized a perdeuterated conjugated polymer, poly[2-(2-ethylhexyloxy-d17)-5-methoxy-d3-1,4-phenylenevinylene-d4] (d-MEH-PPV), with 97% of the protons replaced by deuterons35. Second, OLEDs have to be designed with integrated microwires which generate the oscillating field18. The smaller the OLED pixel relative to the microwire, which narrows down to a width of 150 μm, the lower the inhomogeneity in both static and oscillating magnetic fields—at the cost of EDMR signal-to-noise ratio. The alternating current passed through the microwire generates heat, requiring careful optimization of electrical and thermal conductivity of the monolithic OLED-microwire device18.

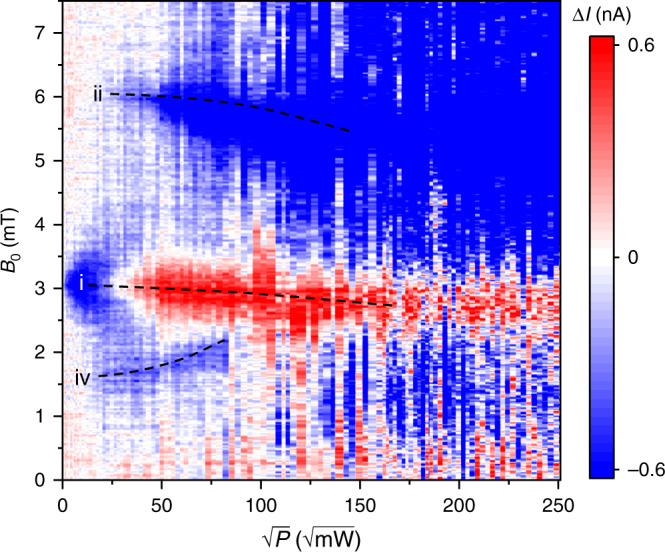

Figure 3 plots the change ΔI of the steady-state DC forward current I0 = 500 nA under 85 MHz RF radiation, as a function of B0 and the square root of the power P of the applied radiation. The dominant Floquet spin state transitions identified in the calculation in Fig. 2 are resolved in the experiment and labeled correspondingly: the power-broadened g ≈ 2 spin resonance which inverts its sign in the spin-Dicke regime with subsequent BSS (i); the two-photon transition and the corresponding BSS of the g ≈ 1 resonance (ii); and the half-field resonance at g ≈ 4 (iv). In principle,

Measured change in spin-dependent OLED current ΔI as a function of driving power.

The dominant features of Fig. 2 are indicated by dashed lines. The relationship

A simple intuitive rationalization of the intriguing two-photon transition can be formulated. Two-photon transitions between the up and down state of a spin-½ species are dipole forbidden. In analogy to light waves, the resonant radiation can be described in the photon picture. A photon has an angular momentum quantum number of 1 and can assume one of the two projection states of either

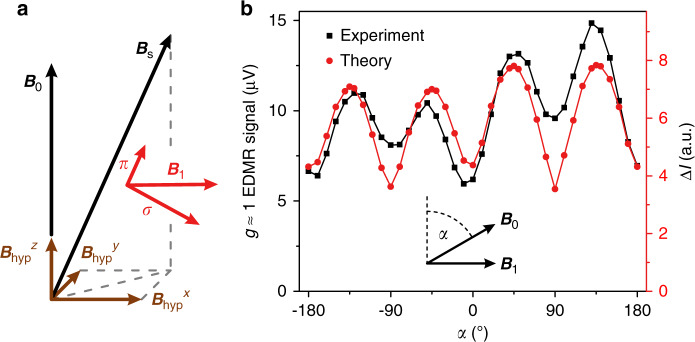

Figure 4a provides an intuitive picture for the emergence of the two-photon transition. Transversal oscillating magnetic-field components are orthogonal to B0, but the latter is superimposed with local static isotropic hyperfine fields. This superposition leads to the effective static magnetic field, Bs, tilted from the z axis by a small but finite angle. Thus, the superposition of B0 and the local hyperfine fields results in a total static field Bs parallel to one component of the oscillating magnetic field, which is sufficient to enable the

Intuitive rationalization of the two-photon transition and the angular dependence of the two-photon g ≈ 1 EDMR signal.

a Sketch of the magnetic-field configuration acting on a spin within a spin pair. Oscillating magnetic-field components (red arrows) parallel (π) and perpendicular (σ) to the effective local quantizing static magnetic field Bs arise from the decomposition of B1 with respect to the total static magnetic field that results from the superposition of B0 and Bhyp. b Angular dependence of the two-photon EDMR resonance measured at f = 22 MHz (black) for the d-MEH-PPV devices. The experimental results match the

Two-photon resonances arise both under parallel and perpendicular excitation. This observation can be explained by the illustration in Fig. 4a: photons of both longitudinal (π) and transversal (σ) polarizations exist even for parallel or perpendicular field configurations. The lower B0, the greater the contributions of the transversal hyperfine fields and the influence of dipolar coupling of spins within the spin pairs, which enable the resonances under fully parallel and perpendicular excitation. We note that a slight asymmetry in the angular dependency can be attributed to additional resonant contributions of the second harmonic of the RF signal generated by the RF amplifier. This second harmonic can be removed by filtering the incident RF radiation using a low-pass filter. Alternatively, we replicate this asymmetry in the calculation in Fig. 4b by introducing a second harmonic resonant contribution amounting to

We conclude that the Floquet ansatz presented here to solve the time-dependent Hamiltonian of a two-level system in the ultrastrong-drive regime provides both an accurate and surprisingly intuitive representation of the complex spin excitations arising under these conditions. These include the spin-Dicke state, which manifests a strong BSS, along with dressed light-matter states, which support dipole-forbidden multiple-quantum transitions. Spin-dependent recombination rates between paramagnetic charge-carrier states in OLEDs offer a remarkably versatile testbed to probe this regime of ultrastrong coupling, visualizing directly the predicted multiple-quantum transitions and fractional g-factor resonances—to our knowledge, better than other known quantum systems at room temperature. The identification of the BSS at room temperature is particularly clear in these solid-state devices compared to any other spectroscopic probe of this phenomenon outside of nuclear magnetic resonance36–38. Similarly, direct signatures of hybrid light-matter Floquet states are observed here to influence spin-dependent OLED currents, much like the Floquet states reported in photoelectron spectroscopy of topological materials39.

The theoretical results of Fig. 2 provide motivation to extend the phase space of the experiment to even higher ratios of

Although we refrain at present from speculating too much on possible technological applications of our study, we do note that a clear feature in theory and experiment is the demonstration that power broadening is suppressed when the spin-Dicke state is formed: the one-photon resonance feature (i) power-broadens linearly with driving field strength B1 when B1 is below the Dicke regime, whereas after inversion of the resonance sign (marked in red in Figs. 2 and 3) broadening of the inverted feature with a further increase in power is minimal. This absence of power broadening implies that the hybrid light-matter state, the spin-Dicke state25, appears to be protected against power broadening precisely because it is a hybrid state. The consequence of this protection should be a dramatically enhanced coherence time, which in turn may turn out to be useful in quantum magnetometry applications. Measuring this increased coherence time in pulsed experiments40 at very high B1 could potentially confirm this hypothesis. Such experiments would require coherent spin manipulation by RF pulses, which are shorter in duration than the RF wave period at the very low Larmor frequencies used here, i.e., subcycle magnetic-resonant coherent control, which is technically feasible with modern pulse synthesizers.

Finally, the work presented here also suggests exciting challenges for materials chemists. The linewidth of the resonances in the calculated spectra of Fig. 2 is determined primarily from the finite inhomogeneous broadening arising from the residual hyperfine field strengths of the deuterated conjugated polymer. By careful design of materials, it may be possible to reduce hyperfine coupling even further, for example, by extending the π-electron system in polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons to lower the interaction between electronic and nuclear magnetic moments. With such advances, it will be possible to resolve resonances at even lower B0 fields and therefore reach even higher effective ratios of B1 to B0.

Details of the computational procedure, including the modifications made to the conventional spin-pair model of spin-dependent recombination in an OLED28,41, are given in Supplementary Note 1.5 along with a list of the model parameters used.

In order to establish and detect ultrastrong electron-spin magnetic resonance drive conditions, we developed a new monolithic OLED device structure with an integrated RF microwire. These small circular (57 µm diameter) single-pixel OLEDs allow for bipolar charge-carrier injection using electron and hole injector layers on top of an electrically and thermally separated thin-film wire capable of producing RF magnetic fields B1 when connected to an RF source. The wire itself runs across the substrate and is shrunk down to 150 μm width beneath the OLED pixel. Details of the layer sequence necessary to achieve electrical and thermal decoupling are given in ref. 18. Further details can be found in Supplementary Note 2. The active polymer, d-MEH-PPV, was dissolved in toluene at a concentration of 4.5 g/L at a temperature of 50–70 °C and deposited by spin-casting at 800 rpm, as described in ref. 35. The layer was sandwiched as a 100 nm thin film between a Ca/Al stack for electron injection and a TiO2 (3 nm)/Au (80 nm)/Ti (10 nm) layer covered with PEDOT:PSS (Ossila Al 4083) for hole injection. The structure is comparable to that used in previous studies of the strong-drive regime, where a different π-conjugated polymer with much larger resonance linewidths was used24. For the study presented here, the active-layer material, the layer stack, and the pixel device geometry were redesigned and optimized in order to allow for larger B1/B0 ratios to be reached. The monolithic single-pixel OLED device was made following a preparation and deposition protocol as illustrated in Jamali et al.18 with the following changes: (i) the active polymer layer where the electron-hole pair recombination takes place was nominally 100 nm thick, consisting of spin-coated perdeuterated d-MEH-PPV; (ii) the sample template preparation included placing the silicon wafer in a dry thermal oxidation furnace at 1000 °C for 78 min, producing a 50 nm SiO2 layer on top of the Si wafer for insulation and better adhesion of the subsequent layer (amorphous SiN); and (iii) an entirely different lateral layout of the templates (cf. Supplementary Fig. 1a) was used compared to that described in Jamali et al.18, providing larger separation between the electrical contacts of the thin-film wire RF source and the device electrodes in order to avoid cross-talk at high RF powers and minimize heating of the OLED during the room temperature measurements. A photograph of the pixel device template is shown in Supplementary Fig. 1a with the pixel located at the image center. An example of the current-voltage characteristics of the device at room temperature is also given in Supplementary Fig. 1b.

The OLED was subjected to a static magnetic field B0 and irradiated with RF radiation with in-plane amplitude B1 using an Agilent N5181A frequency generator and an ENI 510 L RF power amplifier as illustrated in Supplementary Fig. 1a. At the same time, a steady-state electric current was induced with a V = 2.8 V bias using a Keithley voltage source. A Stanford Research (SR570) current amplifier was used to detect changes

The angle-dependence measurements of the two-photon resonance were performed in a separate low-field setup with different OLED samples, described in detail in refs. 5,42. These OLEDs were much larger, with a pixel area of 3.5 mm2. RF excitation generated by an Anritsu MG3740A signal generator and amplified by a HUBERT A 1020 RF amplifier was applied to the sample through a coplanar stripline designed to match a 50 Ω impedance. In contrast to the measurements on the monolithic OLED-microwire structures, these experiments were performed under constant-current conditions with

Supplementary information is available for this paper at 10.1038/s41467-020-20148-6.

This work was supported by the US Department of Energy, Office of Basic Energy Sciences, Division of Materials Sciences and Engineering under Award #DE-SC0000909. The synthesis of the perdeuterated monomer took place at the Australian National Deuteration Facility, which is partly funded by NCRIS, an Australian Government initiative. P.L.B. is an Australian Research Council Laureate Fellow and the synthesis work was supported in part by this Fellowship (FL160100067). J.M.L. and S.B. acknowledge funding by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG, German Research Foundation)—Project-ID 314695032—SFB 1277.

S.J. designed the high-power microwire OLED structure and performed magnetic resonance spectroscopy, with help from H.M., A.N., and H.P. V.V.M. developed the Floquet simulation code and performed all calculations discussed in the paper. T.G., S.B., and S.M. performed additional supporting experiments at low fields. P.L.B. led the synthesis of the perdeuterated conjugated polymer with support from D.M.S., A.E.L., and T.A.D. J.M.L. and C.B. conceived and supervised the project, and wrote the paper with input from all authors.

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

The raw data that support the plots within this paper and the other findings of this study are available from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request.

The Fortran code used for the numerical simulations discussed in this paper is available from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request.

The authors declare no competing interests.

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

6.

7.

8.

9.

10.

11.

12.

13.

14.

15.

16.

17.

18.

19.

20.

21.

22.

23.

24.

25.

26.

27.

28.

29.

30.

31.

32.

33.

34.

35.

36.

37.

38.

39.

40.

41.

42.