- Altmetric

In comparison to conventional discrete-variable (DV) quantum key distribution (QKD), continuous-variable (CV) QKD with homodyne/heterodyne measurements has distinct advantages of lower-cost implementation and affinity to wavelength division multiplexing. On the other hand, its continuous nature makes it harder to accommodate to practical signal processing, which is always discretized, leading to lack of complete security proofs so far. Here we propose a tight and robust method of estimating fidelity of an optical pulse to a coherent state via heterodyne measurements. We then construct a binary phase modulated CV-QKD protocol and prove its security in the finite-key-size regime against general coherent attacks, based on proof techniques of DV QKD. Such a complete security proof is indispensable for exploiting the benefits of CV QKD.

While continuous-variable QKD presents many experimental advantages, a full security proof that addresses the most general attacks and digitized signals in the finite-size regime has so far been lacking. Here, the authors fill this gap in the case of a protocol with a binary phase modulation.

Introduction

Quantum key distribution (QKD) aims at generating a secret key shared between two remote legitimate parties with information-theoretic security, which provides secure communication against an adversary with arbitrary computational power and hardware technology. Since the first proposal in 19841, various QKD protocols have been proposed with many kinds of encoding and decoding schemes. These protocols are typically classified into two categories depending on the detection methods. One of them is called discrete-variable (DV) QKD, which uses photon detectors and includes earlier protocols such as BB841 and B922 protocols. The other is called continuous-variable (CV) QKD, which uses homodyne and heterodyne measurements with photo detectors3–5. See refs. 6,7 for comprehensive reviews of the topic.

Although DV QKD is more mature and achieves a longer distance if photon detectors with low dark count rates are available, CV QKD has its own distinct advantages for a short distance. It can be implemented with components common to coherent optical communication technology and is expected to be cost-effective. Excellent spectral filtering capability inherent in homodyne/heterodyne measurements suppresses crosstalk in wavelength division multiplexing (WDM) channels. This allows multiplexing of hundreds of QKD channels into a single optical fiber8 as well as co-propagation with classical data channels9–15, which makes integration into existing communication network easier.

One major obstacle in putting CV QKD to practical use is the gap between the employed continuous variables and mandatory digital signal processing. The CV-QKD protocols are divided into two branches depending on whether the modulation method of the encoder is also continuous, or it is discrete. The continuous modulation protocols usually adopts Gaussian modulation, in which the sender chooses the complex amplitude of a coherent-state pulse according to a Gaussian distribution3–5,16,17 (see refs. 18,19 for a review). This allows powerful theoretical tools such as Gaussian optimality20,21, and complete security proofs for a finite-size key and against general attacks have been given22. To implement Gaussian protocols with a digital random-number generator and digital signal processing, it is necessary to approximate the continuous distribution with a constellation composed of a large but finite number of complex amplitudes23,24. This is where difficulty arises, and the security analysis has been confined to the asymptotic regime and collective attacks. The other branch gives priority to simplicity of the modulation and uses a very small (usually two to four) number of amplitudes25–28. As for the security analysis, the status is more or less similar to the Gaussian constellation case, and current security proofs are either in the asymptotic regime against collective attacks29–32 or in the finite-size regime but against more restrictive attacks33,34. Hence, regardless of approaches, a complete security proof of CV QKD in the finite-size regime against general attacks has been a crucial step yet to be achieved.

Here we achieve the above step by proposing a binary phase-modulated CV-QKD protocol with a complete security proof in the finite-size regime against general attacks. The key ingredient is an estimation method using heterodyne measurement developed in this paper, which is suited for analysis of confidence region in the finite-size regime. The outcome of heterodyne measurement, which is unbounded, is converted to a bounded value by a smooth function such that its expectation is proved to be no larger than the fidelity of the input pulse to a coherent state. This allows us to use a standard technique to derive a lower bound on the fidelity with a required confidence level in the finite-size regime. The fidelity as a measure of disturbance in the binary modulated protocol is essentially the same as what is monitored through bit errors in the B92 protocol2,35,36. This allows us to construct a security proof based on a reduction to distillation of entangled qubit pairs37,38, which is a technique frequently used for DV-QKD protocols.

Results

Estimation of fidelity to a coherent state

We first introduce a test scheme to estimate the fidelity between an optical state ρ and the vacuum state through a heterodyne measurement. For a state ρ of a single optical mode, the heterodyne measurement produces an outcome

Theorem 1: Let Λm,r(ν) (ν ≥ 0) be a bounded function given by

From Eq. (6), a lower bound on the fidelity between ρ and the vacuum state is given by

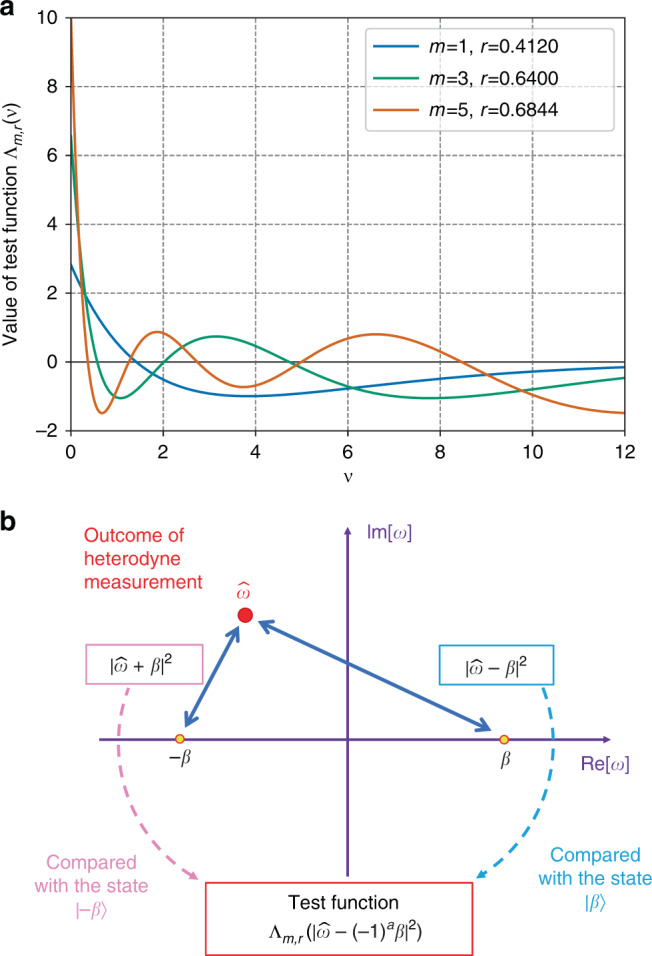

The test scheme to estimate the fidelity.

a Example of the test functions Λm,r used in the estimation. The values of r in the figure are chosen so that the range of Λm,r is minimized for given m. In general, the minimum range of the function Λm,r becomes larger as m increases. The pair (m, r) = (1, 0.4120) was used in the numerical simulation of key rates below. b A schematic description of the usage of obtained outcomes in heterodyne measurement. In order to estimate the lower bound on the fidelity to the coherent states

Extension to the fidelity to a coherent state

Proposed protocol

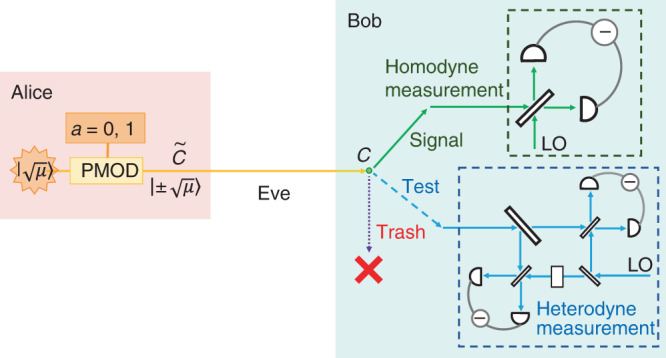

Based on this fidelity test, we propose the following discrete-modulation protocol (see Fig. 2). Prior to the protocol, Alice and Bob determine the number of rounds N, the acceptance probability of homodyne measurement

The proposed continuous-variable quantum key distribution protocol.

Alice generates a random bit a ∈ {0, 1} and sends a coherent state with amplitude

The acceptance probability fsuc(∣x∣) should be chosen to post-select the rounds with larger values of ∣x∣, for which the bit error probability is expected to be lower. It is ideally a step function, but our security proof is applicable to any form of fsuc(∣x∣). The parameter β is typically chosen to be

1. Alice generates a random bit a ∈ {0, 1} and sends an optical pulse

2. For each of the received N pulses, Bob chooses a label from {signal, test, trash} with probabilities psig, ptest, and ptrash, respectively. According to the label, Alice and Bob do one of the following procedures.

[signal] Bob performs a homodyne measurement on the received optical pulse C, and obtains an outcome

[test] Bob performs a heterodyne measurement on the received optical pulse C, and obtains an outcome

[trash] Alice and Bob produce no outcomes.

3. We refer to the numbers of “success” and “failure” signal rounds, test rounds, and trash rounds as

4. For error correction, they use

5. Bob computes and announces the final key length

Security proof

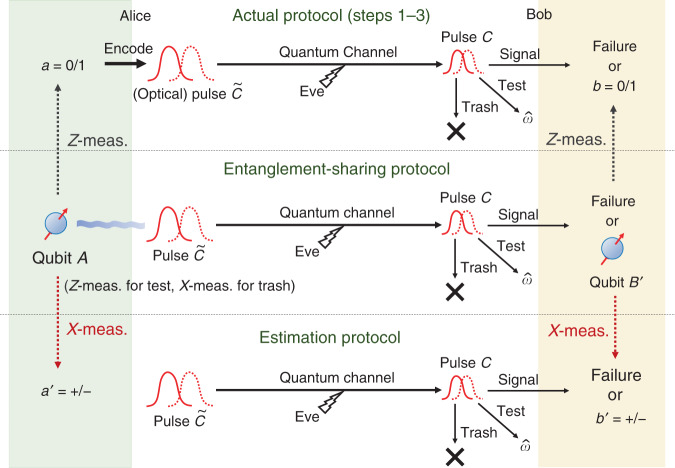

We determine a sufficient amount of the privacy amplification according to Shor and Preskill37,40, which has been widely used for the DV-QKD protocols. We consider a coherent version of Steps 1 and 2, in which Alice and Bob share an entangled pair of qubits for each success signal round, such that their Z-basis measurement outcomes correspond to the sifted key bits a and b. For Alice, we introduce a qubit A and assume that she entangles it with an optical pulse

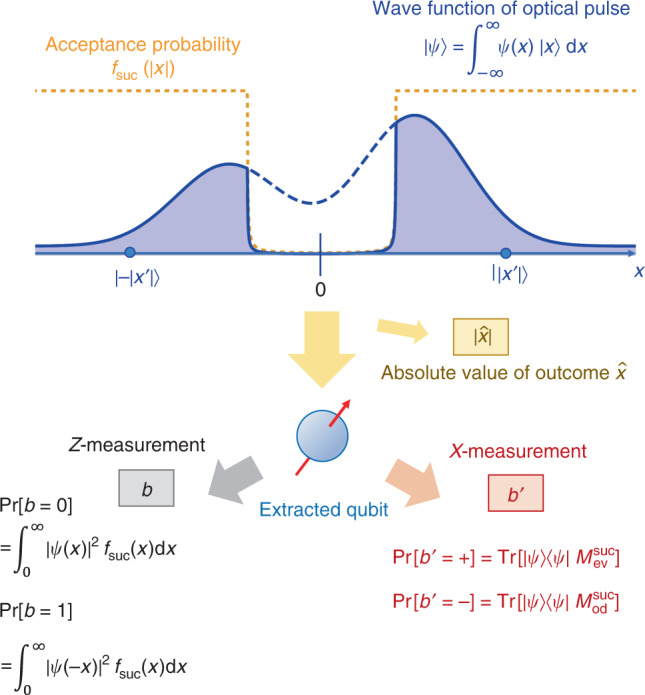

Bob’s qubit extraction in the entanglement-sharing protocol.

Bob performs on the optical pulse a non-demolition projective measurement, with which the absolute value of the outcome of homodyne measurement

To clarify the above observation, we introduce an entanglement-sharing protocol defined in Box 2. This protocol leaves

Relation between three protocols.

The actual protocol and the estimation protocol are related through the entanglement-sharing protocol. After the entanglement-sharing protocol, Alice and Bob are left with the observed data

The Shor-Preskill argument connects the amount of privacy amplification to the so-called phase error rate. Suppose that, after the entanglement-sharing protocol, Alice and Bob measure their

To cover the finite-size case as well, we need a more rigorous statement on the upper bound. For that purpose, we define an estimation protocol in Box 3 (see also Fig. 4). The task of proving the security of the actual protocol is then reduced to construction of a function

At this point, it is beneficial for the analysis of the phase error statistics to clarify what property of the optical pulse C is measured by Bob’s X-basis measurement in the estimation protocol (see Fig. 3). Let Πev(od) be the projection to the subspace with even (resp. odd) photon numbers. (Πev + Πod = 1C holds by definition.) Furthermore, since Πev − Πodd is the operator for an optical phase shift of π, we have

As an intermediate step toward our final goal of Eq. (15), let us first derive a bound on the expectation value

It is expected that a meaningful bound is obtained only for κ, γ ≥ 0. Decreasing fidelity

To find a function B(κ, γ) satisfying Eq. (25), let us define an operator

With B(κ, γ) computed, we can rewrite Eq. (25) using Eqs. (22)–(24) to obtain a relation between

The security in the finite-size regime is proved as follows. The fact that the bound given in Eq. (28) is true for all the states ρAC allows us to use Azuma’s inequality42 to evaluate the fluctuations around the expectation value, leading to an inequality

Although Eq. (29) includes

[signal] Bob performs a quantum operation on the received pulse C specified by the CP map

[test] Bob performs a heterodyne measurement on the received optical pulse C, and obtains an outcome

[trash] Alice measures her qubit A on X basis to obtain

1″–3″. Same as Steps

4″. Alice and Bob measure each of their

Numerical simulation

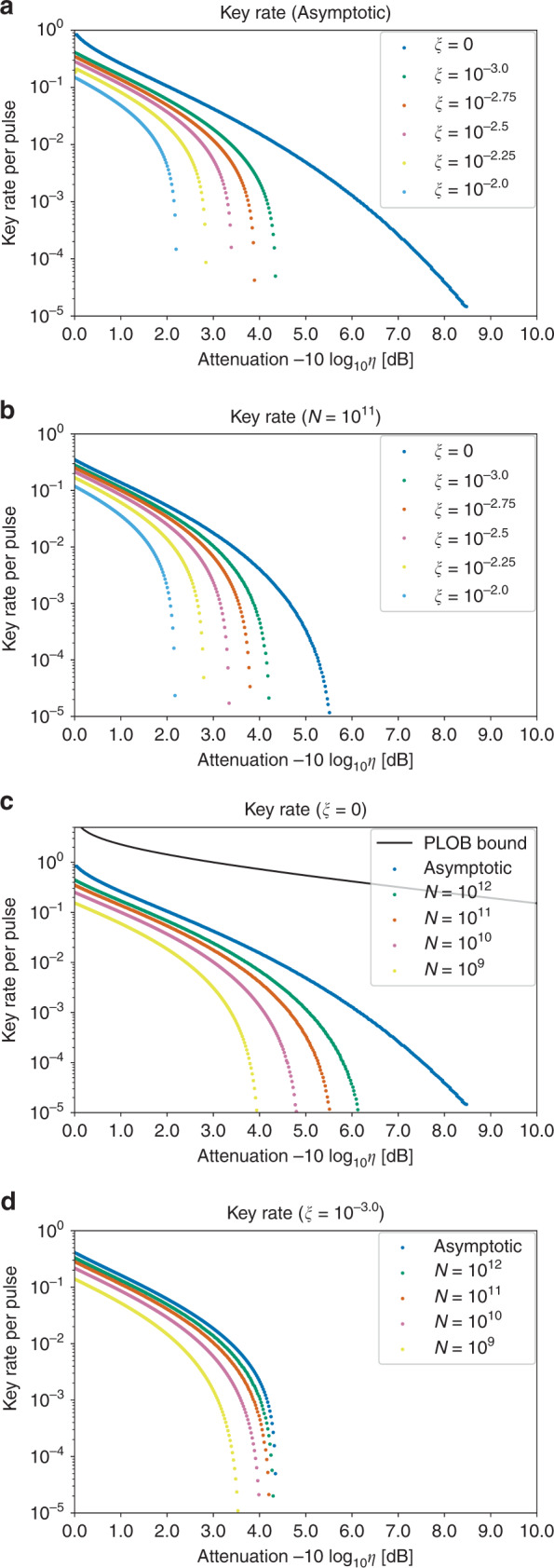

We simulated the net key gain per pulse

Figure 5 shows the key rates of our protocol in the asymptotic limit N → ∞ and finite-size cases with N = 109–1012 for ξ = 10−2.0–10−3.0 and 0. (Note that from the results of the recent experiments8,44,47, excess noise with ξ = 10−2.0–10−3.0 at the channel output seems reasonable. Furthermore, the state-of-the-art experiments8 work at 0.5 GHz repetition rate, which implies that total number of rounds N = 109–1012 can be achieved in a realistic duration.) For the noiseless model (ξ = 0), the asymptotic rate reaches 8 dB. In the case of ξ = 10−3.0, it reaches 4 dB, which is comparable to the result of a similar binary modulation protocol proposed in ref. 29. As for finite-size key rates, we see that the noiseless model shows a significant finite-size effect even for N = 1012. On the other hand, with a presence of noises (ξ = 10−3.0) the effect becomes milder, and N = 1011 is enough to achieve a rate close to the asymptotic case. This may be ascribed to the cost of the fidelity test. In order to make sure that the fidelity is no smaller than 1 − δ, the statistical uncertainty of the fidelity test must be reduced to O(δ). As a result, approaching the asymptotic rate of ξ = 0 will require many rounds for the fidelity test.

The net key gain per pulse

The abscissa represents attenuation in decibel, i.e.,

Discussion

Numerically simulated key rates above were computed on the implicit assumption that Bob’s observed quantities are processed with infinite precision. Even when these are approximated with a finite set of discrete points, we can still prove the security with minimal degradation of key rates. For the heterodyne measurement used for the test in the protocol, assume that a digitized outcome ωdig ensures that the true value

In comparison with recent asymptotic analyses31,32 of discrete-modulation CV QKD, our protocol achieves lower key rates and much shorter distance. Since ours is the first attempt of applying the proof technique of DV QKD to CV QKD, there is much room for possible improvement. We sacrificed the optimality for simplicity in deriving the operator inequality. The definition of the phase error is not unique and there may be a better choice. The trash rounds were introduced for technical reasons, but we are not sure whether they are really necessary. Nonetheless, we believe that the dominant reason for the difference lies in the fact that our protocol uses only two states. In contrast, the protocols considered in refs. 31,32 use four or more states in signal or test modes. The genuine binary protocol was analyzed in ref. 29, and the key rate derived there is comparable to ours.

In order to improve the presented finite-size key rate, a promising route will thus be increasing the number of states from two. Our fidelity test can be straightforwardly generalized to monitoring of such a larger constellation of signals, and we will be able to confine the adversary’s attacks more tightly than in the present binary protocol. As for the proof techniques to determine the amount of privacy amplification, there are two possible directions. One is to generalize the present DV-QKD-inspired approach of estimating the number of phase errors in qubits to the case of qudits. The other direction is to seek a way to combine the existing analyses31,32,48 of discrete-modulation CV-QKD protocols, which have been reported to yield high key rates in the asymptotic regime, to our fidelity test. Although either of the approaches is nontrivial, we believe that the present results will open up new direction toward exploiting the expected high potential of CV QKD with an improved security level.

In summary, we proved the security of a binary-modulated CV-QKD protocol in the finite-size regime while completely circumventing the problems arising from the analog nature of CV QKD. We believe that it is a significant milestone toward real-world implementation of CV QKD, which has its own advantages.

Methods

Proof of Theorem 1 and Eq. (8)

In this section, we prove Theorem 1 stated in the main text and derive Eq. (8) as a corollary of Theorem 1.

Proof: From Eq. (1), the expectation value of

The following three properties hold for In,m:

(i)In,m = 0 for m ≥ n ≥ 1.

This results from orthogonality relations of the associated Laguerre polynomials, that is,

(ii)(−1)mIn,m > 0 for n > m ≥ 0.

This property is shown as follows. First, the associated Laguerre polynomials satisfy the following recurrence relation for m ≥ 149:

(iii)I0,m = 1 for m ≥ 0.

This also follows from property (i) and Eq. (36) for n = 1 and m ≥ 1, which leads to I0,m = I0,0 = 1.

Combining properties (i), (ii), and (iii) shows Eq. (6).

Eq. (8) in the main text is derived as the following corollary.

Corollary 1: Let

Proof: From Eq. (6) of Theorem 1, for any odd positive integer m, we have

Detail of the security proof

In this section, we prove the security of the proposed protocol in the main text. This section consists of several subsections. In the first subsection, we give a definition of security, which is standard in the literature. The security condition is divided into two conditions, secrecy and correctness. Since the correctness is trivially satisfied, it is the secrecy that is the focus of the security proof. The second subsection explains how the secrecy condition is reduced to Eq. (15) of the estimation protocol, which bounds the number of phase errors. The third subsection lays the groundwork for the full security proof by deriving the inequality (27) involving three operators relevant for the quantities observed in the signal, the test, and the trash round in the estimation protocol. After proving a general lemma (Lemma 1), an explicit form of the upper bound B(κ, γ) satisfying Eq. (27) is given as a corollary (Corollary 2) of the lemma. Finally, the fourth subsection uses Azuma’s inequality and Corollaries 1 and 2 to derive an explicit form of

1. Definition of security in the finite-size regime. We evaluate the secrecy of the final key as follows. When the final key length is Nfin ≥ 1, we represent Alice’s final key and an adversary’s quantum system as a joint state

For correctness, we say a protocol is ϵcor-correct if the probability for Alice’s and Bob’s final key to differ is bounded by ϵcor. Our protocol achieves

When the above two conditions are met, the protocol becomes

2. Reduction to the estimation protocol. Here we show that Eq. (15) in the estimation protocol implies ϵsct-secrecy of the actual protocol with

The secrecy of Alice’s final key can be determined from the X-basis property of her

We remark that the encryption of

3. Derivation of the operator inequality. The aim of this subsection is to construct B(κ, γ) which fulfills the operator inequality (27). Let

Lemma 1: Let Π± be orthogonal projections satisfying Π+Π− = 0. Suppose that the rank of Π± is no smaller than 2 or infinite. Let M± be self-adjoint operators satisfying Π±M±Π± = M± ≤ α±Π±, where α± are real constants. Let

Proof: We choose orthonormal vectors

As a corollary, we derive Eq. (27) as follows.

Corollary 2: Let

Proof: Let us first observe that the operator Πfid defined in Eq. (20) can be rewritten as follows:

4. Derivation of the finite-size bound. Here we construct the function

(i)

(ii)

(iii)

(iv)We also define

We will make use of Azuma’s inequality42. We define stochastic processes

Proposition 1 (Azuma’s inequality52,53): Suppose

We define constants

Next, we will construct a deterministic bound on

The function

Combining Eq. (30) and Eq. (31), we obtain Eq. (15) by setting

Models for numerical simulation of key rates

In what follows, we normalize quadrature x such that a coherent state

For the simulation of the key rate

We assume that Bob sets

We assume that the number of “success” signal rounds

Under these assumptions, the key rate

| η [dB] | Key rate | (κ, γ) | μ | xth | psig | ptest |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parameters for N = 1011 and ξ = 0 | ||||||

| 0.5 | 2.17 × 10−1 | (44.9, 1.92) | 0.554 | 0.451 | 0.821 | 0.172 |

| 1.0 | 1.38 × 10−1 | (32.4, 1.38) | 0.514 | 0.532 | 0.821 | 0.172 |

| 1.5 | 8.71 × 10−2 | (24.9, 1.01) | 0.487 | 0.610 | 0.816 | 0.176 |

| 2.0 | 5.36 × 10−2 | (20.3, 0.741) | 0.442 | 0.724 | 0.831 | 0.160 |

| 2.5 | 3.16 × 10−2 | (17.0, 0.538) | 0.459 | 0.771 | 0.788 | 0.205 |

| 3.0 | 1.75 × 10−2 | (14.6, 0.381) | 0.451 | 0.855 | 0.767 | 0.227 |

| 3.5 | 8.92 × 10−3 | (13.6, 0.262) | 0.446 | 0.941 | 0.706 | 0.289 |

| 4.0 | 4.15 × 10−3 | (12.6, 0.175) | 0.442 | 1.03 | 0.624 | 0.371 |

| 4.5 | 1.50 × 10−3 | (11.4, 0.107) | 0.439 | 1.13 | 0.522 | 0.473 |

| 5.0 | 3.23 × 10−4 | (9.98, 0.059) | 0.438 | 1.25 | 0.370 | 0.626 |

| 5.5 | 1.63 × 10−5 | (8.78, 0.031) | 0.443 | 1.37 | 0.126 | 0.869 |

| Parameters for N = 1011 and ξ = 10−3.0 | ||||||

| 0.5 | 1.79 × 10−1 | (23.5, 1.60) | 0.491 | 0.489 | 0.854 | 0.137 |

| 1.0 | 1.13 × 10−1 | (17.9, 1.19) | 0.466 | 0.567 | 0.853 | 0.138 |

| 1.5 | 6.95 × 10−2 | (14.3, 0.889) | 0.450 | 0.645 | 0.848 | 0.143 |

| 2.0 | 4.07 × 10−2 | (11.9, 0.666) | 0.442 | 0.724 | 0.831 | 0.160 |

| 2.5 | 2.20 × 10−2 | (10.1, 0.487) | 0.439 | 0.808 | 0.804 | 0.187 |

| 3.0 | 1.02 × 10−2 | (8.85, 0.345) | 0.440 | 0.898 | 0.758 | 0.233 |

| 3.5 | 3.56 × 10−3 | (7.72, 0.232) | 0.447 | 0.999 | 0.674 | 0.316 |

| 4.0 | 5.29 × 10−4 | (6.70, 0.147) | 0.463 | 1.11 | 0.484 | 0.505 |

| Parameters for N = 1012 and ξ = 0 | ||||||

| 0.5 | 2.68 × 10−1 | (82.9, 2.26) | 0.616 | 0.421 | 0.864 | 0.133 |

| 1.0 | 1.69 × 10−1 | (54.9, 1.56) | 0.556 | 0.504 | 0.874 | 0.123 |

| 1.5 | 1.08 × 10−1 | (40.3, 1.11) | 0.518 | 0.590 | 0.873 | 0.124 |

| 2.0 | 6.76 × 10−2 | (31.3, 0.798) | 0.493 | 0.670 | 0.868 | 0.128 |

| 2.5 | 4.12 × 10−2 | (26.5, 0.575) | 0.475 | 0.750 | 0.852 | 0.145 |

| 3.0 | 2.41 × 10−2 | (23.2, 0.408) | 0.466 | 0.834 | 0.829 | 0.168 |

| 3.5 | 1.32 × 10−2 | (20.1, 0.275) | 0.449 | 0.919 | 0.803 | 0.195 |

| 4.0 | 6.93 × 10−3 | (17.7, 0.184) | 0.443 | 1.01 | 0.772 | 0.226 |

| 4.5 | 3.15 × 10−3 | (16.4, 0.115) | 0.434 | 1.10 | 0.698 | 0.300 |

| 5.0 | 1.14 × 10−3 | (14.6, 0.065) | 0.427 | 1.21 | 0.596 | 0.402 |

| 5.5 | 3.29 × 10−4 | (12.9, 0.036) | 0.423 | 1.32 | 0.467 | 0.531 |

| 6.0 | 3.23 × 10−5 | (10.8, 0.017) | 0.421 | 1.45 | 0.240 | 0.759 |

| Parameters for N = 1012 and ξ = 10−3.0 | ||||||

| 0.5 | 2.09 × 10−1 | (29.4, 1.71) | 0.513 | 0.474 | 0.906 | 0.089 |

| 1.0 | 1.32 × 10−1 | (21.7, 1.25) | 0.482 | 0.554 | 0.909 | 0.086 |

| 1.5 | 8.23 × 10−2 | (16.9, 0.928) | 0.462 | 0.633 | 0.909 | 0.086 |

| 2.0 | 4.92 × 10−2 | (13.8, 0.689) | 0.450 | 0.712 | 0.899 | 0.096 |

| 2.5 | 2.74 × 10−2 | (11.5, 0.502) | 0.444 | 0.797 | 0.888 | 0.107 |

| 3.0 | 1.36 × 10−2 | (9.82, 0.355) | 0.442 | 0.886 | 0.858 | 0.137 |

| 3.5 | 5.28 × 10−3 | (8.26, 0.237) | 0.446 | 0.989 | 0.834 | 0.161 |

| 4.0 | 1.17 × 10−3 | (7.13, 0.151) | 0.458 | 1.10 | 0.701 | 0.293 |

Supplementary information

Supplementary information is available for this paper at 10.1038/s41467-020-19916-1.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by Cross-ministerial Strategic Innovation Promotion Program (SIP) (Council for Science, Technology and Innovation (CSTI)); CREST (Japan Science and Technology Agency) JPMJCR1671; JSPS KAKENHI Grant Number JP18K13469.

Author contributions

T.M., K.M., T.S. and M.K. contributed to the initial conception of the ideas, to the working out of details, and to the writing and editing of the manuscript.

Data availability

Data sharing not applicable to the article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

Code availability

Computer codes to calculate the key rates are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

References

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

6.

7.

8.

9.

10.

11.

12.

13.

14.

15.

16.

17.

18.

19.

20.

21.

22.

23.

24.

25.

26.

27.

28.

29.

30.

31.

32.

33.

34.

35.

36.

37.

38.

39.

40.

41.

42.

43.

44.

45.

46.

47.

48.

49.

50.

51.

52.

53.

54.

55.

Finite-size security of continuous-variable quantum key distribution with digital signal processing

Finite-size security of continuous-variable quantum key distribution with digital signal processing