- Altmetric

Social media has become a modern arena for human life, with billions of daily users worldwide. The intense popularity of social media is often attributed to a psychological need for social rewards (likes), portraying the online world as a Skinner Box for the modern human. Yet despite such portrayals, empirical evidence for social media engagement as reward-based behavior remains scant. Here, we apply a computational approach to directly test whether reward learning mechanisms contribute to social media behavior. We analyze over one million posts from over 4000 individuals on multiple social media platforms, using computational models based on reinforcement learning theory. Our results consistently show that human behavior on social media conforms qualitatively and quantitatively to the principles of reward learning. Specifically, social media users spaced their posts to maximize the average rate of accrued social rewards, in a manner subject to both the effort cost of posting and the opportunity cost of inaction. Results further reveal meaningful individual difference profiles in social reward learning on social media. Finally, an online experiment (n = 176), mimicking key aspects of social media, verifies that social rewards causally influence behavior as posited by our computational account. Together, these findings support a reward learning account of social media engagement and offer new insights into this emergent mode of modern human behavior.

Despite the popularity of social media, the psychological processes that drive people to engage in it remain poorly understood. The authors applied a computational modeling approach to data from multiple social media platforms to show that engagement can be explained by mechanisms of reward learning.

Introduction

What drives people to engage, sometimes obsessively, with others on social media? In 2019, more than four billion people spent1 several hours per day, on average, on platforms such as Instagram, Facebook, Twitter, and other more specialized forums. This pattern of social media engagement has been likened to an addiction, in which people are driven to pursue positive online social feedback2,3 to the detriment of direct social interaction and even basic needs like eating and sleeping4,5.

Although a variety of motives might lead people to use social media6, the popular portrayal of social media engagement as a Skinner Box for the modern human suggests it represents a form of reinforcement learning (RL)7 driven by social rewards. Yet despite this common portrayal, empirical evidence for social media engagement as reward-based behavior has been elusive. In the present research, we developed and applied a computational approach to large scale online datasets of social media use to directly test whether, and how, reward learning mechanisms contribute to social media behavior. In doing so, we sought to provide new insights into this emergent mode of human interaction while testing a learning theory model of real-life human social behavior on an unprecedented scale.

In online social media platforms, feedback on one’s behavior often comes in the form of a “like”—a signal of approval from another user regarding one’s post2—which is assumed to function as a social reward. Indeed, several lines of research support the idea that “likes” engage similar motivational mechanisms as other, more basic, types of rewards such as food or money. In humans, brain imaging studies have consistently shown that likes8,9, and other social rewards, are processed by neural and computational mechanisms closely overlapping with those processing non-social rewards10–14. Although neuroscientific studies are largely constrained to the laboratory, such findings suggest that social media use might reflect the process of reward maximization, similar to what is observed across species in response to non-social rewards.

Reward learning processes on social media platforms should also be evident in behavior. Indeed, the receipt of likes has behavioral consequences consistent with reward learning. For example, the number of likes received for a post predicts satisfaction with that post, and in turn, more self-reported happiness15,16. Similarly, a user’s social media activity increases after a post, suggestive of reward anticipation17, and users provide more social feedback to others after receiving feedback themselves18. In addition to its direct effect on reward, the subjective value of likes is also influenced by social comparison in a way similar to non-social rewards3,19,20, suggesting that social rewards, just like non-social rewards21, might be relative, rather than absolute in nature. Together, these existing studies support the idea that social media engagement reflects reward mechanisms.

However, as most studies of online social rewards to date utilize self-report methods22,23, direct evidence for a social reward learning account of behavior on social media is lacking. Furthermore, studies that do apply RL approaches to social media data have typically not sought to delineate psychological mechanisms underlying social media use, but instead to optimize software that interacts with users (e.g., by training recommender systems24). In addition, results from the few studies that have taken a quantitative approach to human behavior are mixed. In one study, negative evaluation of a post—a type of social punishment—led to deterioration in the quality of future posts, rather than the improvement predicted by learning theory25. By contrast, in another study, receiving more replies for a post on a specific social media discussion forum predicted a subsequent increase in the time spent on that forum relative to others, consistent with learning theory26. Thus, it remains unclear whether basic mechanisms of reward learning can help explain actual behavior on social media.

In the present research, we directly test whether social media engagement can be formally characterized as a form of reward learning. By analyzing more than one million posts from over 4000 individual users on multiple distinct social media platforms (see Methods), we assess, using computational modeling, how the putative social rewards received for posts in the past (e.g., the likes received when posting a “selfie”) can help explain future behavior. Our computational modeling approach allows us to explicitly test how cross-species reward learning mechanisms contribute to this uniquely human mode of social behavior27. We also confirm, using an online experiment resembling common social media platforms (n = 176), that social rewards causally influence behavior as predicted by our reward learning account.

Computational learning theory posits specific behavioral patterns that would characterize online behavior as an expression of reward learning. A seminal empirical insight is that when animals (e.g., rodents in a Skinner box) can select the timing of their instrumental responses (e.g., when and how often to press a lever), the latency of responding (the inverse of the response rate) is negatively related to the rate of accrued rewards28. That is, a lower reward rate produces longer response latencies. Reinforcement learning theory provides both a normative explanation and a mechanistic machinery for this regularity: the more reward one receives, the shorter the average latency between responses should be, because acting more slowly results in a longer delay to the next reward, and the cost of this delay—the opportunity cost of time—is directly related to the average reward rate29. As consequence, when animals have learned, through interaction with the environment, that the average reward rate is higher, actions should be made faster because further rewards would be foregone by slower and fewer responses.

Although this RL theory was developed to explain animal behavior in laboratory tasks, on timescales of seconds and minutes, the theoretical relationship between the average reward rate and response latency is not tied to a specific timescale. Consequently, if social media taps into basic learning mechanisms, social media behavior should exhibit the same relationship between response latency—the time between successive social media posts—and the (social) reward rate. In other words, we hypothesize that a type of real-life behavior, on timescales rarely, if ever, investigated in the laboratory, exhibits this key signature of reward learning. Finally, we confirm the causal influence of the social reward rate on posting response latencies with an online experiment, designed to mimic key aspects of social media platforms.

Results

Reward learning on social media

We tested our hypothesis that online social behavior, in the form of posts, follows principles of reward learning theory in four independent social media datasets (see Methods) (total NObs = 1,046,857, NUsers = 4,168) with computational modeling. These datasets came from four distinct social media platforms, where people post pictures and, in response, receive social reward in the forms of “likes.” In Study 1 (NUsers = 2,039), we tested our hypothesis in a large dataset of Instagram posts30 (average number of posts per individual = 418, see Supplementary Table 1 for additional descriptive statistics). Instagram exemplifies modern social media, with over 1 billion registered users, and its format—focused primarily on simple postings and the receipt of likes as feedback—makes it a unique case study. However, because there are significant economic motives on Instagram and similar platforms31, an assessment of reward learning on Instagram could be limited to some extent by the possibility of fraudulent accounts and “fake likes,” among other strategic uses32. We therefore replicated and extended Study 1 in Study 2 (NUsers = 2,127) with data from three different topic-focused social media sites (discussion forums focused on Men’s fashion, Women’s fashion, and Gardening, see Methods), where economic motives are less likely (average number of posts per individual = 91, see Supplementary Table 1 for descriptive statistics). Finally, we conducted an online experiment (Study 3, NParticipants = 176), designed to mimic key aspects of social media platforms, in which we manipulated the social reward rate to verify its causal impact on response latencies.

Social rewards predict social media posting

We conceptualized the act of posting on a social media platform (e.g., Instagram) as free-operant behavior in a Skinner box with one response option (e.g., a single lever), where responses are followed by reward (i.e., likes). As outlined, a key prediction from learning theory for such situations, in which the agent can decide when to respond, is that the latency between responses should be affected by the average rate of rewards28,29. Before formally testing our computational hypothesis, we evaluated, in two complementary and model-independent ways, whether social media behavior was sensitive to social rewards.

First, we drew inspiration from classic work in animal learning theory, which established that response rates, an aggregate measure of response latency, typically follow a saturating positive (i.e., hyperbolic) function of reward rates28. This relationship, known as the quantitative law of effect28, is a signature of reward driven behavior (especially on interval schedules of reinforcement28). To directly test whether social media behavior exhibits this pattern, we compared how well a hyperbolic function explained the relationship between likes and response rates relative to a linear function (Supplementary Note 1). We found that the “quantitative law of effect” explained behavior better than a linear relationship in all four social media datasets (mean R2: Study 1 = 0.43, Study 2: = 0.37, see Supplementary Note 1), demonstrating that an aggregate measure of response latencies on social media exhibits a classic signature of reward learning28.

Second, we defined a high resolution measure of response latency (τPost) as the time between two successive social media posts (similar to the interval between responses in human laboratory tasks and in animal free-operant behavior, see Fig. 1), and tested whether τPost was predicted by the history of likes using Granger causality analysis (see Methods). Granger causality is established if a variable (e.g., likes) improves on the prediction of a second variable (e.g., τPost) over and above earlier (lagged) values of the second variable in itself. To ascertain the selectivity of this method, we first applied it to simulated data from generative models where the ground truth was known (causality or no causality). We then fine-tuned the analysis parameters (the lag number, see Supplementary Note 2) to reliably detect Granger causality in data simulated from our reward learning model, which we introduce next, but not from models without learning (in which likes are unrelated to behavior, see Supplementary Note 2). Applying this optimized analysis method to the empirical data showed that likes Granger-caused τPost in all four datasets (Study 1: Z̃ = 23.65, p < 0001; Study 2: Men’s Fashion: Z̃ = 3.94, p < 0001; Women’s Fashion: Z̃ = 14.16, p < 0001; Gardening: Z̃ = 6.78, p < 0001). Together, these results demonstrate that the history of social rewards (i.e., likes) influenced both the rate and the time distribution of social media posting. Such reward sensitivity is a minimal criterion for more formally testing the explanatory power of learning theory.

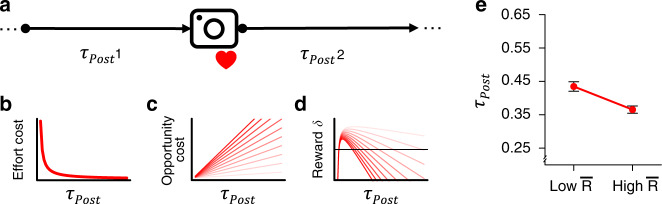

Schematic illustration of the computational hypothesis.

a The model describes how τPost, the latency to the next social media post (denoted by the “camera” icon), is shaped by social rewards. Each post is followed by social reward (denoted by the “heart” symbol), which varies in number. The model adjusts the response policy, or threshold, which determines τPost, to maximize the average net rate of reward. b The

Modeling the dynamics of social media behavior

Having established that social media behavior is sensitive to reward, we next developed a generative model, based on RL theory of free-operant behavior in non-human animals29. The key principle of this theory is that agents should balance the effort costs of responding and the opportunity costs of passivity (i.e., the posting-related rewards one misses while not posting) to maximize the average net (i.e., gains minus losses) reward rate29. The consequence is that average response latencies should be shorter when the average reward rate is higher. This prediction holds both when the amount of reward is a direct function of the number of responses (i.e., ratio schedules of reinforcement) and when rewards become available at specific time points (i.e., interval schedules of reinforcement).

Building directly on these principles, our

We simulated the model (~250,000 data points from 1000 simulated users, with random parameter values, see Supplementary Methods for details) to generate predictions for reward learning on social media. According to learning theory, τPost should be lower when the average reward rate is relatively higher. To verify this prediction in a simple manner, we rank-transformed and standardized

Our empirical analysis of the four social media platforms tested these model-based predictions with model estimation, statistical analyses, and generative model simulations. We optimized the parameters of the

Study 1

We first modeled online behavior in the Instagram dataset of Study 130. Model comparison showed that the

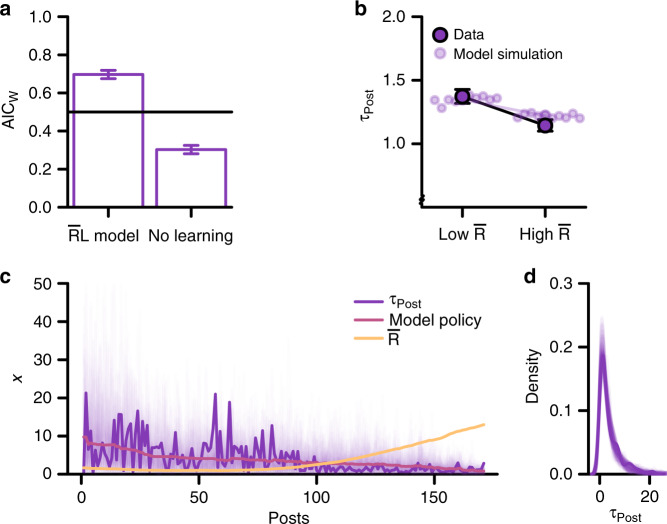

Behavior on Instagram is explained by reward learning (Study 1).

a Model comparison shows that the

This conclusion was robust to the removal of individuals with especially short or long (outside the 20th and 80th deciles) average τPost, or with few (or many) posts (see Supplementary Note 3), which confirms that the fit of the

According to our theoretical framework, responses should be faster when the subjective reward rate is higher. Similar to how we derived model predictions (c.f., Fig. 1d), we used the model-based estimate of

Study 1: Alternative models

To test the specificity of the

Study 1: model simulations

In addition to demonstrating a model’s superior fit to the data, strong support for a model depends on its ability to reproduce the effects of interest37. To confirm the model fitting results, we therefore generatively simulated the

Study 2

To replicate and extend the results of Study 1, we collected data from three distinct social media sites (see Methods) which, in contrast to Instagram, focus on special interest topics (Men’s fashion, Women’s fashion, Gardening, respectively). Much activity on these social media sites is focused on textual exchange rather than images, but all three contain prolific “threads”—collections of posts focused on a specific topic—with predominantly image-based content (e.g., “What are you wearing today?”, “Post pictures of your garden”), with many thousands of posts each. We limited our analyses to posts with user-generated images from such threads (see Methods and Supplementary Methods), but verify in the Supplementary Note 5 that the results are qualitatively identical when including text-based posts.

We again tested the hypothesis that social media behavior reflects social reward learning by estimating the same

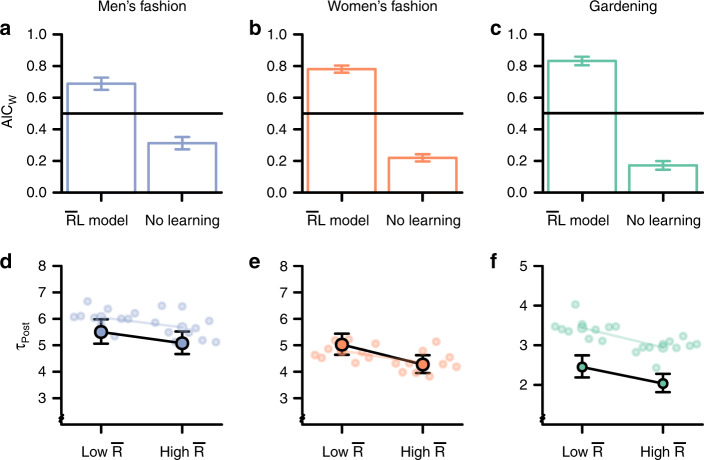

Signatures of reward learning on three social media sites (Study 2).

a–c Model comparison shows that the

As in Study 1, we used the model-based estimate of

We again conducted generative model simulations of the

Study 2: Social comparison in social reward learning

The preceding analyses showed that people dynamically adjust their social media behavior in response to their own social rewards, as predicted by reward learning theory—a theory originally developed to test the effects of nonsocial rewards (e.g., food) in solitary contexts. However, given the intrinsically social context of social media use, we speculated that reward learning online could be modulated by the rewards others receive. In the Supplementary Note 9 we provide preliminary support for the hypothesis that reward learning, at least on the social media platforms we analyzed in Study 2, may be modulated by social comparison.

Individual differences in reward learning on social media

Having established that reward learning can help explain social media behavior, we next asked whether individuals differ in the ways they learn from rewards on social media. To address this issue, we used the parameter estimates of the basic

More specifically, we used the three parameters of the original

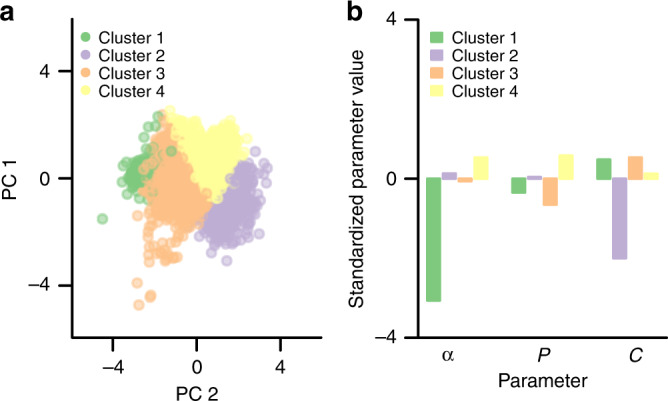

Computational phenotypes in reward learning on social media.

a Cluster analysis (n = 4168 independent individuals from Study 1 & 2) of the estimated

Figure 4b illustrates the four putative computational phenotypes. For example, individuals in cluster 1 are characterized by a relatively low learning rate (ɑ). Such individuals are especially insensitive to social rewards in their behavior (and naturally, the

Study 3

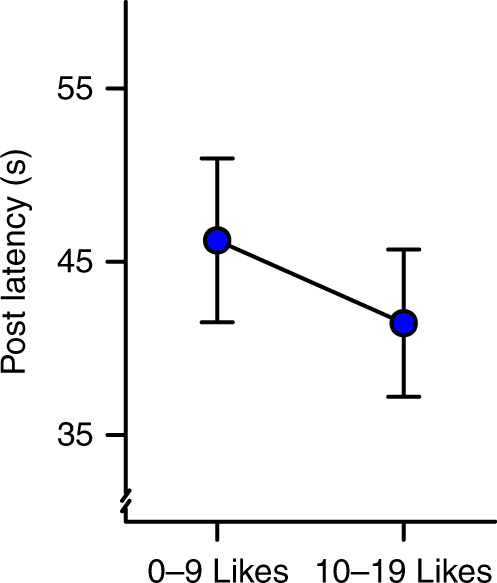

Finally, to provide direct evidence that the social reward rate affects posting latencies, we conducted an online experiment in which we experimentally manipulated social rewards and observed posting response latencies. The experiment was designed to capture key aspects of social media, such as Instagram. Participants (n = 176) could post “memes”—typically, an amusing image paired with a phrase that is popular on real social media—as often and whenever they wanted during a 25 min. online session (total number of posts = 2,206, see Supplementary Methods for details). Participants received feedback on their posts in the form of likes (0–19) from other ostensible online participants (“users”, see Supplementary Fig. 5 for an overview of the experiment). Participants themselves could also indicate “likes” for memes posted by other users. To test whether a higher social reward rate causes shorter response latencies in posting, we increased or decreased the average number of likes participants received between the first and second halves of the session (low reward: 0–9 likes/post, high reward: 10–19 likes/post, drawn from a uniform distribution, with direction of change counter-balanced across subjects). As expected, mixed effects regression (see Methods) showed that the average post latency was longer when the social reward rate was lower (0–9 likes/post) relative to higher (10–19 likes/post): β = 0.109, SE = 0.044, z = 2.47, p = .013 (see Fig. 5), corresponding to a 10.9% difference. Notably, participants who reported more followers on Instagram exhibited weaker effects of likes on their behavior (see Supplementary Note 11). This finding parallel how individuals with more Instagram followers in Study 1 exhibited more diminished marginal utility of likes (see “Study 1” above and Supplementary Note 4). These results further support the validity of our experiment in assessing the psychology of real-world social media use. We report additional analyses and robustness checks in Supplementary Note 11.

Experimental manipulation of social reward rates (Study 3).

The estimated effect of social reward rate condition on posting latencies in the online experiment (n = 176 independent individuals, see Supplementary Fig. 5 for a design overview). Results are presented as means (fixed effects regression estimates) ±1 SE of the regression estimates from from mixed-effects regression.

To directly relate the experimental results of Study 3 to our model-based analyses of online behavior in Studies 1 and 2, we used the

Discussion

In an age where our social interactions are increasingly conducted online, we asked what drives people to engage in social media behavior. Across two studies of four large online datasets, we found that social media behavior exhibited a signature pattern of reward learning, such that computational models inspired by RL theory, originally developed to explain the behavior of non-human animals, could quantitatively account for online behavior. This account was further supported by experimental data, in which manipulated reward rates affected the latency of social media posted in line with this reward learning model. Together, these results provide an important advance in our understanding of people’s use of online social media, an increasingly pervasive and profoundly consequential arena for human interaction in the 21st century.

Our results provide clear evidence that behavior on social media indeed follows principles of reward maximization, and thereby give credence to the popular portrayal of social media engagement as a Skinner Box for the modern human. These observations, along with their formal modeling, have broad implications for understanding and predicting multiple aspects of online behavior, including dating (e.g., learning from outcomes on dating apps), social norms, and prejudice43. For example, it has been argued that online expressions of moral outrage, and in turn polarization44, are fueled by social feedback, such as likes, in accordance with the principles of reward learning45. Our findings and theoretical framework provides a plausible mechanistic basis for such processes, and thereby further expand the scope of simple reinforcement learning mechanisms for explaining seemingly complex social behaviors, such as social exclusion38, behavioral traditions46, and socio-cultural learning47.

Our computational model of social media behavior draws from RL theory originally intended to explain how non-human animals select the vigor of their responses by encoding the average net rate of rewards29. Apart from providing a normative explanation for key behavioral regularities (e.g., the “matching law”28), an important aspect of this theory is the idea that

More generally, our results indicate that dopamine inspired RL theory may help to explain real-life individual behavior on timescales that are orders of magnitude larger than typically investigated in the lab. In turn, this insight might contribute to a more mechanistic perspective on both healthy and maladaptive (e.g., addictive4,5) aspects of social media use, with the potential to inspire novel, theoretically grounded design solutions or interventions. Such interventions could be individualized by applying computational phenotyping to an individual’s existing social media record (e.g., by increasing the effort cost of posting for individuals characterized by low C), thus providing ideographic approaches developed from theoretical models tested on large-scale data. Although our data do not speak directly to whether intense social media use is maladaptive or addictive in nature, it suggests a new approach for asking such critical questions.

Naturally, there are many possible reasons for posting on social media in addition to reward seeking, ranging from self-expression to relational development6. While our research focused on how social rewards explain behavior, it does not preclude the potentially important roles of other motivations. Incorporating relational considerations in the

Our results raise several new questions regarding the role of reward in social media behavior. First, while our analysis of anonymous, real-world social media data precluded demographic characterization of users, it is possible that certain demographic factors, such as age, may moderate the effect of reward learning in online behavior. For example, adolescents tend to be more sensitive than adults to social rewards and punishments49, and thus our results may be particularly informative to questions of adolescent social media behavior. An examination of the developmental trajectories of the computational phenotypes in social reward learning identified here, and their relations to individual differences in psychological traits, could further illuminate age effects in online behavior. Furthermore, while our research focused on the effect of social rewards (i.e., likes) on posting behavior, negative feedback, which is rampant on many social media platforms (e.g., down votes), is also likely to drive learning. The RL framework we proposed here may also be extended to include such social punishments. For example, treating social punishments as reinforcement with negative utility would, in principle, allow direct application of the

In conclusion, our findings reveal that basic reward learning mechanisms contribute to human behavior on social media. Understanding modern online behavior as an expression of social reward learning mechanisms offers a new window into the psychological and computational mechanisms that drive people to use social media while illuminating the link between basic, cross-species mechanisms and uniquely human modes of social interaction.

Methods

Social media datasets

Study 1 was based on data from a previously published study (see30 for further information), in which data collection was based on a random sample of individuals who partook in a specific photography contest on Instagram in 2014. We find no evidence that contest participation was related to posting behavior (see Supplementary Note 12). The dataset was fully anonymized. To allow for analyses of learning, we excluded all individuals with less than 10 posts50. For Study 1, the final dataset consisted of 851,946 posts from 2,039 individuals. For Study 2, we obtained three datasets from three different topic-focused (Men’s fashion: styleforum.net, Women’s fashion: forum.purseblog.com, Gardening: garden.org, see Supplementary Methods for details) social media discussion forums using web scraping techniques51 on publicly accessible data. The datasets were fully anonymized, and only included the time stamps and likes associated with posts in prolific threads focused on user-generated images (e.g., pictures of one’s clothing, see Supplementary Methods). For our analyses, we focused on posts with user-generated images, and, in analogy to Study 1, removed all users with fewer than ten image posts. The Study 2 dataset consisted of 190,721 posts from 2,127 individuals (Men’s fashion: N = 543, Women’s fashion: N = 773, Gardening: N = 813). This research was conducted in compliance with the US Office for Human Research Protections regulations (45 CFR 46.101 (b)).

Experiment

The experiment was conducted on Amazon Mechanical Turk, and approved by the ethical review board of the University of Amsterdam, The Netherlands. See the Supplementary Methods for additional information.

Description of the R ¯ L

The

For each post, the

The initial response policy (i.e., for t = 1) was estimated as a free parameter (0 ≤ P ≤ ∞). The subtraction term in Eq. (1) implements the momentous effect of the average reward rate (e.g., changes in motivational state),

The response policy, which determines τPost, is adjusted based on the prediction error, δ, the difference between the experienced reward (Rt) and the reference level:

The reference level explicitly takes into account both the effort cost of fast responding and the opportunity cost of slow responding (Fig. 1b, c), which is determined by the subjective estimate of the average net reward

The

Thereby, the model can learn the instrumental value of slower vs. faster responses. For example, if

However, regardless of whether slower or faster responses are rewarded, an increase in the average reward rate (Eq. 5) results in a higher opportunity cost of time (Eq. 2), which in turn results in shorter response latencies (Eq. 2, and Fig. 1d).

If either

Statistical analysis

All model estimation, simulations, and statistical analyses were conducted using R. All reported p-values are two-tailed. Granger causality analysis was applied to first differenced data using the plm package for panel-data analysis (see Supplementary Methods for details)55. Mixed effects modeling was conducted with the lme456 and glmmTMB57 packages. All log-linear mixed effects models included a random intercept for each user. In the statistical analyses, the dependent variable τPost was log transformed (as the time between events follows an exponential distribution) to improve linearity. All predictors were standardized within individual (i.e., centering within cluster) to produce individual-level estimates58. Degrees of freedom, test statistics, and p-values were derived from Satterthwaite approximations in the lmerTest package59. The key statistical analyses were in addition repeated using log-linear regression models with cluster-corrected standard errors to ensure robustness (see Supplementary Table 7). Prior to k-means clustering, the

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Research Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Source data

Unsupported media format: /dataresources/secured/content-1765946278449-89ff3051-c1b3-409c-bedc-6ae508cc7a19/assets/41467_2020_19607_MOESM4_ESM.zip

3/16/2021

A Correction to this paper has been published: 10.1038/s41467-021-22067-6

Supplementary information

Supplementary information is available for this paper at 10.1038/s41467-020-19607-x.

Acknowledgements

We thank Andreas Olsson for helpful comments on an earlier version of the manuscript, and Lucas Molleman for valuable suggestions concerning the experimental design. Work on this article was supported by grant from the Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research to DMA (VICI 016.185.058). PNT acknowledges funding support from the Swiss National Science Foundation (100019_176016).

Author contributions

B.L. conceived of the study. B.L. developed the study in discussion with M.B., P.T. and D.A., B.L. designed and implemented the computational models, and conducted all analyses. M.B. and A.C. collected and processed the data for Study 2. B.L., D.S. and D.A. designed the behavioral experiment. D.S. coded the behavioral experiment and collected data. B.L. and D.A. wrote the manuscript. B.L., P.T. and D.A. edited the manuscript and contributed to the interpretation of the results.

Data availability

The availability of the dataset analyzed in Study 1 is described in ref. 30. The datasets analyzed in Study 2 are available on reasonable request from the corresponding author. The dataset analyzed in Study 3 is available on the Open Science Framework (https://osf.io/765py/). A reporting summary for this article is available as a Supplementary Information file. Source data are provided with this paper.

Code availability

Code for estimating the

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

References

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

6.

7.

8.

9.

10.

11.

12.

13.

14.

15.

16.

17.

18.

19.

20.

21.

22.

23.

24.

25.

26.

27.

29.

30.

31.

32.

33.

34.

35.

36.

37.

38.

39.

40.

41.

42.

43.

44.

46.

47.

48.

49.

50.

51.

52.

53.

54.

55.

56.

57.

58.

59.

60.

A computational reward learning account of social media engagement

A computational reward learning account of social media engagement