We present the first example of an unprecedented and fast aryl C(sp2)–X reductive elimination from a series of isolated Pt(IV) aryl complexes (Ar = p-FC6H4) LPtIVF(py)(Ar)X (X = CN, Cl, 4-OC6H4NO2) and LPtIVF2(Ar)(HX) (X = NHAlk; Alk = n-Bu, PhCH2, cyclo-C6H11, t-Bu, cyclopropylmethyl) bearing a bulky bidentate 2-[bis(adamant-1-yl)phosphino]phenoxide ligand (L). The C(sp2)–X reductive elimination reactions of all isolated Pt(IV) complexes follow first-order kinetics and were modeled using density functional theory (DFT) calculations. When a difluoro complex LPtIVF2(Ar)(py) is treated with TMS–X (TMS = trimethylsilyl; X= NMe2, SPh, OPh, CCPh) it also gives the corresponding products of the Ar–X coupling but without observable LPtIVF(py)(Ar)X intermediates. Remarkably, the LPtIVF2(Ar)(HX) complexes with alkylamine ligands (HX = NH2Alk) form selectively either mono- (ArNHAlk) or diarylated (Ar2NAlk) products in the presence or absence of an added Et3N, respectively. This method allows for a one-pot preparation of diarylalkylamine bearing different aryl groups. These findings were also applied in unprecedented mono- and di-N-arylation of amino acid derivatives (lysine and tryptophan) under very mild conditions.

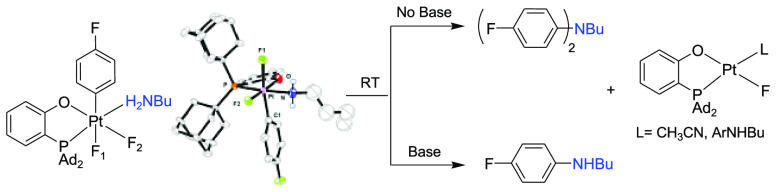

The formation of the new C–X (X = C, heteroatom) bonds via reductive elimination from a group 10 M(IV) atom is the product-forming step in a variety of catalytic oxidative transformations that have attracted much attention in the last two decades.1,2 As compared to the more common M(II) counterparts, high-valent d6 metal complexes have a greater number of donor atoms at the metal center, which may imply greater competitiveness when it comes to the C–X bond formation and, hence, may require more careful control over the reaction selectivity.3 For example, a competitive formation of C(sp3)–N, C(sp3)–F, and C(sp3)–C(sp2) bonds can be observed at a Pd(IV) center in a single complex (Scheme 1a), as has been reported by Sanford and co-workers .4 Notably, a preference for the C(sp3)–X vs C(sp2)–X reductive elimination is typical for this and similar systems.5 As a result of significant efforts targeting isolation and characterization of various Pd(IV) and, more recently, Ni(IV) organometallic derivatives exhibiting clean C–X bond reductive elimination reactivity,1 this chemistry is now well-established, although some “blind spots” remain. As a consequence, the intermediacy of organopalladium(IV) species is now routinely proposed in various palladium-catalyzed C–X coupling reactions performed under sufficiently oxidizing conditions.6 In turn, thanks to a greater kinetic inertness,7 Pt(IV) complexes can serve a better role as models to study some still poorly characterized C–X bond coupling reactions.3,8−11 Surprisingly, in spite of some notable progress in this field, a number of aryl C(sp2)–X coupling reactions involving well-characterized isolable Pt(IV) compounds (e.g., for X = Cl, O, N) have never been observed.12

C–N Elimination from a M(IV) Center

Focusing specifically on a C–N bond formation at a M(IV) center, most of the accomplished research deals with the C(sp3)–N coupling involving an SN2 attack at the metal-bound alkyl groups lacking β-hydrogen atoms.1c,10c,13 In turn, stabilized amide anions are typically employed as coupling partners combining accessibility, chemical robustness, and appreciable reactivity as nucleophile.1,4,10,11,13,14 While many catalytic C(sp2)–N coupling reactions were proposed to proceed via putative Pd(IV) intermediates, in none of the cases were such intermediates characterized.6b Only one report of a well-characterized C(sp2)–N(sulfonyl, acyl) coupling of isolated Pd(IV) amido aryl complexes has recently been published by one of us (Scheme 1b).15 In turn, to the best of our knowledge, no C(sp2)–N(hydrocarbyl) reductive coupling reactions of any isolable group 10 M(IV) amines complexes have been characterized so far. Considering the importance of metal-catalyzed and metal-mediated N-mono- and N,N-diarylation, especially in the synthesis of biologically active compounds,16,17 we report here the preparation of aryl Pt(IV) complexes with a series of alkylamines, as well as experimental and computational characterization of their unusually facile aryl C(sp2)–N(Alk) reductive elimination reactivity. By merely changing the basicity of the system, selective and high-yielding mono- or diarylation of the coordinated amine can be achieved (Scheme 1c). The developed approach has been used for an unprecedented mono- and di-NH-arylation of partially protected lysine and tryptophan under very mild conditions.

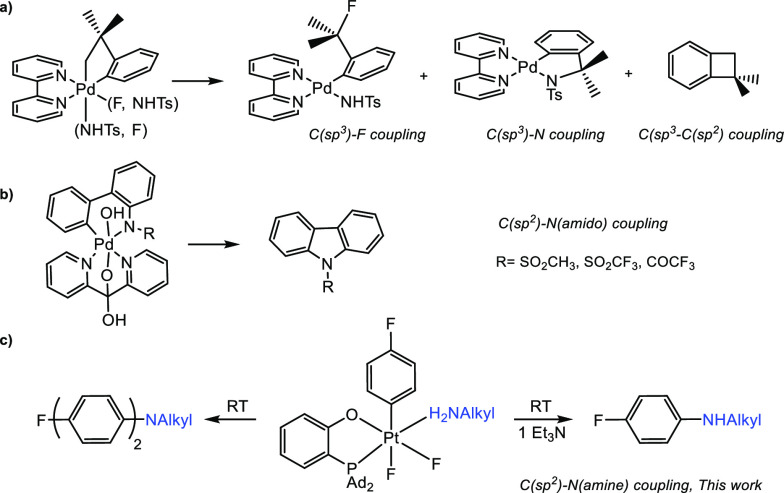

Recently, we presented the first example of a highly selective aryl–F reductive elimination reaction from an isolated Pt(IV) aryloxide fluoro complex (Scheme 2).8 Notably, similar reactions involving heavier halogens, Br and I, are easier to observe.9 We proposed that the exclusive C–F bond formation was sterically enforced by the presence of the bulky mesityl and 2-[bis(adamant-1-yl)phosphino]phenoxide (P–O) ligands. Thus, this ligand scaffold might also be efficient for enabling other difficult aryl–X elimination reactions (e.g., X = Cl, CN, O, N(alkyl)) at a Pt(IV) center, hopefully in a selective manner.

Aryl–F Elimination from a Pt(IV) Center

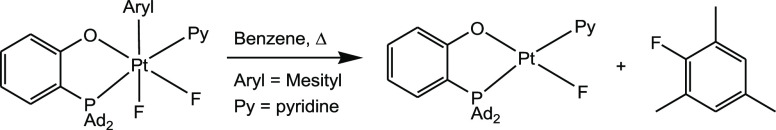

The target aryl (P–O)Pt(IV) precursors 2a (X = CN), 2b (X = 4-OC6H4NO2), and 2c (X = Cl) have been prepared using Pt(IV) aryl difluoride 1 and an appropriate TMS–X reagent at room temperature (Scheme 3), isolated, and fully characterized.18 Notably, the p-nitrophenoxo complex 2b has been characterized by single-crystal X-ray diffraction (Figure S1), confirming that the reaction of 1 with TMS–4-OC6H4NO2 led to the selective replacement of the fluoride ligand Fa, trans to the aryl, giving the product with the mutual trans arrangement of the aryl and 4-nitrophenoxo groups. The remaining fluoride ligand Fb showed the characteristic upfield (below −300 ppm) 19F NMR signals for all three complexes, thus revealing the same diastereoselectivity of these ligand substitution reactions. Analogous compounds 2d (X = OPh), 2e (X = SPh), 2f (X = CCPh), and 2g (X = NMe2) were not detected by NMR spectroscopy when 1 and the corresponding TMS–X reagents were reacted either at room temperature (4e,g) or upon heating to 65 °C (4d,f). Instead, the formations of Ar–X coupling products 4d–4g, along with TMS–F and the corresponding Pt(II) complex 3, were observed, thus suggesting that, for 1d–1g, the C–X reductive elimination reactions from transient 2d–2g are faster than the formation of complexes 2 from 1 and the corresponding TMS–X.

Selective Ar–X Reductive Elimination at a Pt(IV) Center

The isolated Pt(IV) cyanide 2a demonstrated the formation of Ar–CN product following a clean first-order kinetics in EtCN solutions (k353K = 3.41 ± 0.44 × 10–4 s–1, ΔG⧧ = 26.5 kcal/mol, Figure S2) and could be produced in ca. 70% yield after 1.5 h at 80 °C. The reaction was only slightly slowed by the presence of 10 equiv of pyridine (k353K = 1.21 ± 0.01 × 10–4 s–1, ΔG⧧ = 27.2 kcal/mol), thus suggesting that the pyridine dissociation step is virtually irreversible in this Ar–CN coupling reaction. Both the 4-nitrophenoxo (2b) and the chloro (2c) analogues were engaged in similar transformations to form the corresponding Ar–X coupled derivatives 4b and 4c in 38% and 83% yields, respectively.18 Notably, neither Ar–O nor Ar–Cl coupling at a Pt(IV) center have been documented before. Our observation of the elimination of the Ar–X coupled products 4b and 4c pushes the limits of possible applications of aryl Pt(IV) complexes for the Ar–X bond formation and provides one with an opportunity to learn more about such reactions.

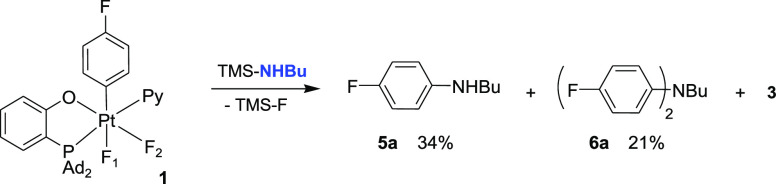

As no examples of C(sp2)–N(Alk) elimination have been reported at a d6 metal center before this work, to the best of our knowledge, we decided to explore in more detail the formation of Ar–N coupled products such as 4g where no Pt(IV) intermediates were detected by the NMR spectroscopy (Scheme 3). When a TMS derivative of a primary alkylamine, TMS–NHnBu, was used in the reaction with complex 1, the aniline 5a formed in 34% yield at room temperature overnight (Scheme 4). Unexpectedly, the reaction was accompanied by the accumulation of significant (21% yield)19 amounts of the diarylamine (4-FC6H4)2NBu, 6a (Scheme 4).

Formation of N-Mono- and N,N-Diarylation Products in the Reaction of 1 with TMS–NHnBu

To check if the reaction may be stepwise and 5a can be involved in another arylation with 1, an authentic sample of 5a was combined with 1 to lead to a quantitative formation of 6a within 1 h at room temperature. Thus, the reaction between 5a and 1 to give 6a appears to be faster than the F-for-NHnBu exchange between 1 and TMS–NHnBu and subsequent elimination of 5a.

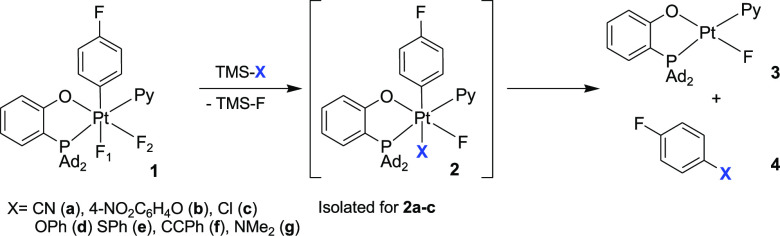

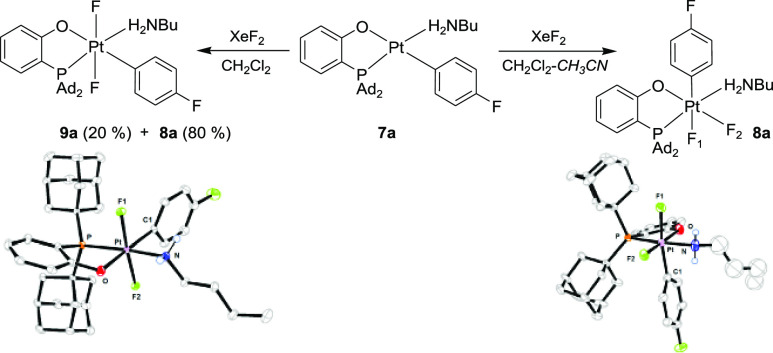

Assuming that the reaction in Scheme 4 may have involved a highly reactive Pt(IV) alkylamido aryl intermediate, we sought to prepare an expectedly more robust Pt(IV) analogue containing coordinated alkylamine (P–O)PtIVF2(p-FC6H4)(NH2nBu), 8a. To that end, (P–O)PtII(p-FC6H4)(NH2nBu), 7a, was reacted with XeF2. Performing the reaction in a CH2Cl2–CH3CN mixture afforded the new moderately stable Pt(IV) complex 8a in 74% isolated yield. Complex 8a was structurally characterized by single-crystal X-ray diffraction (Scheme 5) and was shown to be an analogue of complex 1, with H2NnBu in place of the pyridine as a ligand. The n-butyl fragment in the complex is severely disordered and could not be modeled reliably by discrete atoms with realistic thermal parameters. When the same reaction of complex 7a and XeF2 was performed in neat CH2Cl2, a 4:1 mixture of 8a and the trans-difluoride 9a was formed that was isolated and characterized by X-ray diffraction (Scheme 5).

Synthesis of Pt(IV) n-Butylamine Complexes 8a and 9a

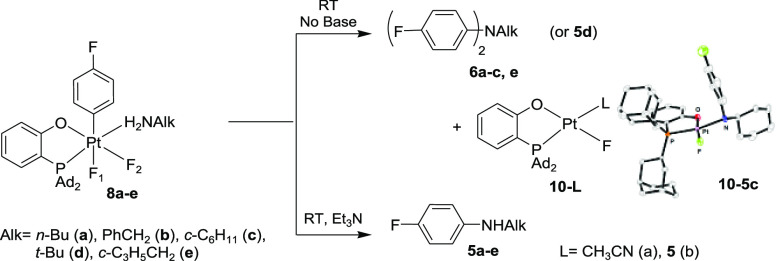

Complex 9a showed no Ar–N coupling reactivity even when heated at 50 °C in a CH2Cl2–CH3CN mixture. By contrast, its cis isomer 8a underwent an exclusive Ar–N reductive elimination in the same solvent already at room temperature, but instead of the expected monoarylamine n-BuNHAr, 5a, the diarylamine n-BuNAr2, 6a, was produced in 89% NMR yield, along with Pt(II) fluoro complexes 10–L (Scheme 6, top).20 The identity of 6a was confirmed by NMR spectroscopy and mass spectrometry. The C–N coupling of 8a followed a first-order kinetics (k298 = 3.7 ± 0.5 × 10–5 s–1, ΔG⧧ = 23.5 kcal/mol). No intermediates were observed by 19F NMR spectroscopy.

Ar–N(Alk) Bond Formation at a Pt(IV) Center

Remarkably, only the monoarylated product 5a was formed in 97% yield after 1 h of reaction of 8a at 20 °C in the presence of 1 equiv of an external base, Et3N (Scheme 6, bottom). No 6a was observed under these conditions. Similar to the external base-free reaction leading to the diarylamine 6a, the C–N elimination of 8a in the presence of 1 equiv. (0.013 mmol) of Et3N to form the monoarylamine 5a followed a first-order kinetics but roughly 10 times faster (k298 = 4.9 ± 0.7 × 10–4 s–1, ΔG⧧ = 21.9 kcal/mol, Figure S3). Thus, the external base accelerates the elimination of the monoarylamine 5a from 8a, thus making this reaction much faster than the subsequent arylation of 5a by a second equivalent of 8a and leaving the second arylation out of competition. The accelerating effect of Et3N additives on the first arylation step and the absence of such an effect on the second arylation step is explained in subsections 2.5.4 and 2.5.5 in the Computational Studies section. Notably, with 2 equiv of Et3N, the reaction of 8a to form 5a was even faster and was complete within 30 min at 25 °C.

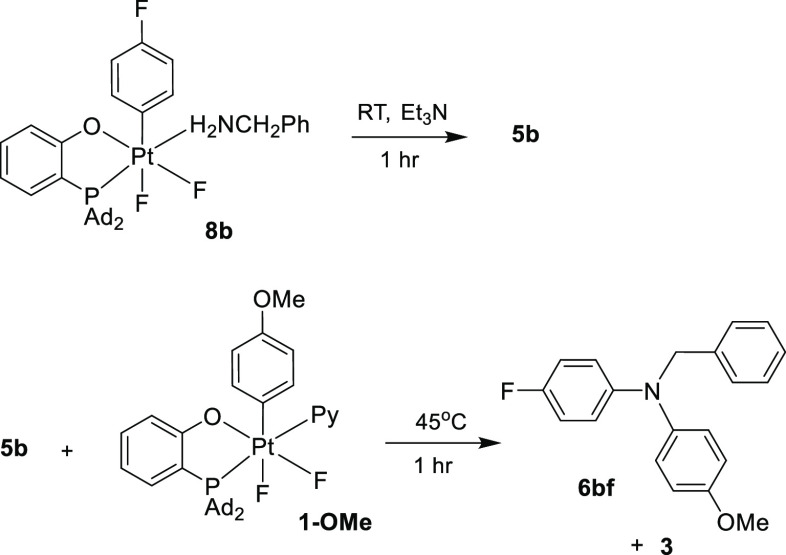

Having analyzed the C–N coupling reactivity of the Pt(IV) n-butylamine aryl complex 8a, we next looked at the reactivity of some analogous complexes (P–O)PtIVF2(p-FC6H4)(NH2Alk) containing other primary alkylamines as ligands, PhCH2NH2 (8b), c-C6H11NH2 (8c), and t-BuNH2 (8d). Similar to 8a, complexes 8b and 8c also readily undergo double N-arylation in a 2:1 CH2Cl2/MeCN solution to form the derived (4-FC6H4N)2Alk products 6b and 6c in 93% and 44% yields, respectively (Scheme 6). By contrast, the bulkier t-BuNH2 derivative 8d gives the monoarylated product 5d only in a low 15% yield along with a number of unidentified byproducts. Hence, the increasing steric bulk of the primary alkylamine ligand used in this reaction, n-BuNH2 ≈ PhCH2NH2 < c-C6H11NH2 < t-BuNH2, appears to affect both the N-arylation selectivity, by disfavoring the formation of diarylated products, and the overall N-arylation efficiency, which also decreases in this direction. Notably, a cyclopropylmethylamine (c-C3H5CH2NH2) analogue 8e reacts cleanly to form the diarylamine 6e as the only organic product without the formation of any cyclopropane ring-opening products. These diarylation reactions are also not inhibited by 1 equiv of butylated hydroxytoluene (BHT), thus arguing against realization of a radical mechanism.

Similar to the n-butylamine complex 8a, the presence of a Et3N additive triggered the C–N coupling of the benzylamine adduct 8b and the cyclohexylamine complex 8c to produce selectively the derived monoarylamines 5b (95%) and 5c (98%), respectively, within 1.5 h at room temperature.17 For the tert-butylamine complex 8d, the yield of the derived monoarylamine 5d rose from 15% to ca. 50% in the presence of Et3N. The identity of the organic products was confirmed by NMR spectroscopy, MS, and single-crystal X-ray diffraction analysis of 4-FC6H4NHCy–(P–O)Pt(II) derivative (10–5c, Scheme 6). Finally, the addition of equimolar amounts of n-BuNH2 and Et3N directly to the pyridine complex 1 leads to the formation of the monoarylamine 5a in >90% NMR yield.

Having analyzed the reactivity trends related to the formation of monoarylalkylamines 5 versus diarylalkylamine products 6 that we observed in the reactions of the respective Pt(IV) p-fluorophenyl complexes (P–O)PtIVF2(Ar)(NH2Alk), 8a–8d (Ar = p-C6H4F), we decided to probe the effect of the aryl ligand Ar on these reactions. An electron-richer p-methoxyphenyl n-butylamine complex 8f and an electron-poorer 3,5-difluorophenyl analogue, 8g, have been prepared, and their C–N coupling reactivity has been characterized (Scheme 7). The p-methoxyphenyl complex 8f, an electron-richer analogue of 8a, showed a reactivity that is similar to that of 8a. This complex reacted in a 2:1 CH2Cl2/MeCN solution at 20 °C to form the expected diarylation product n-BuN(4-MeOC6H4)2, 6f, as the only organic product, in the absence of an external base, and the monoarylation product n-BuNH(4-MeOC6H4), 5f, in the presence of 1 equiv of Et3N.

Ar–N(Alk) Bond Formation Involving Various Ar Groups

A different behavior was observed for the 3,5-difluorophenyl complex 8g, an electron-poorer analogue of 8a (Scheme 7). In this case, the monoarylamine n-BuNH(3,5-F2C6H3), 5g, was observed as the major product, both in the absence of an external base (54% NMR yield after 3 h at 45 °C) and in the presence of 1 equiv of Et3N (97% NMR yield after 1 h at 20 °C). The distinct reactivity of 8g and 8f in N-arylation reactions will be discussed in subsection 2.5.6 of the Computational Studies section.

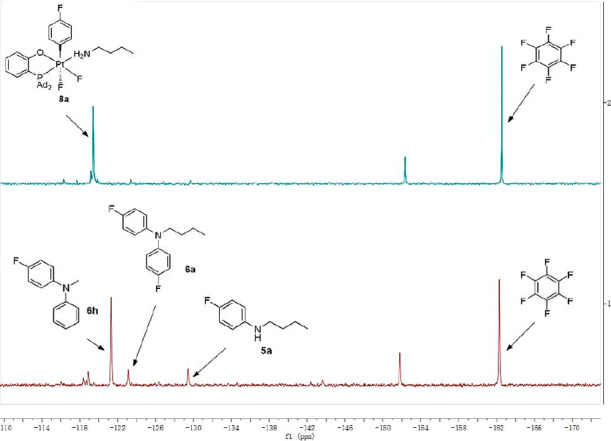

These results (Scheme 7) suggest that, in general, there is a delicate balance between the formation of N-monoarylamines 5 and their N,N-diaryl analogues 6, which are produced in a parallel reaction between 5 and the second equivalent of the Pt(IV) aryl complex 8. This balance is affected, besides the presence of Et3N additives, by the identity of the aryl ligand in 8. For example, when a monoarylalkylamine PhNHMe, 5h, was added to a solution of the 4-fluorophenyl complex 8a (see the 19F NMR spectrum in Figure 1, top), the added amine was N-arylated and the derived product Ph(4-FC6H4)NMe, 6h, formed in 73% NMR yield. Only small amounts of 5a and 6a were observed (Figure 1, bottom), resulting from a background reaction of 8a (see Scheme 6). This result demonstrates that the intermolecular N-arylation of the free amine 5h with 8a is faster as compared to, formally, the intramolecular N-arylation of the coordinated n-butylamine amine ligand present in 8a.

Fragments of 19F NMR spectra of the respective reaction mixtures, demonstrating a competitive arylation of monoarylamines PhNHMe, 5h, and p-FC6H4NHnBu, 5a, formed in situ: the starting complex 8a (top) and a reaction mixture of 8a and 5h (bottom).

On the other hand, when the same monoarylalkylamine 5h was added to a solution of an electron-poorer Pt(IV) 3,5-difluorophenyl complex 8g, the intermolecular N-arylation of the added amine was barely noticeable, so that only a trace amount of the derived diarylamine Ph(3,5-F2C6H3)NMe, 6h, was observed. Here, the major reaction product was the monoarylamine 5g that resulted from the intramolecular N-arylation of the coordinated n-butylamine ligand present in 8g (Scheme 7, left). This result demonstrates that the intramolecular N-arylation of the n-butylamine ligand in 8g is now faster than the intermolecular N-arylation of 5h or 5g.

As discussed in section 2.5.6, this change in the reaction selectivity compared to 8a results from the electron-poorer Pt(IV) center in 8g being slower to exchange its coordinated n-butylamine ligand for 5h or 5g in the step preceding N-arylation of these exogenous amines.

The ability of monoarylalkylamines 5 to undergo second arylation with suitable Pt(IV) aryl complexes, 8 or 1 (vide supra), opens the possibility to generate unsymmetrically substituted N–Ar–N–Ar′-alkylamines in a stepwise manner under mild conditions. In support of this notion, the addition of 5b to a solution of a p-methoxyphenyl pyridine Pt(IV) complex, 1-OMe (Scheme 8), led to the clean formation of the diarylalkylamine 6bf bearing two aryl groups of different electronic demand after 1 h at room temperature. Furthermore, two arylation reactions involving two different aryl Pt(IV) complexes can be performed sequentially without isolation of an intermediate monoarylamine 5.

One-Pot Synthesis of an Unsymmetrical Diarylamine 6bf

For example, reacting the p-fluorophenyl Pt(IV) complex 8b in the presence of 1 equiv of Et3N for 1 h followed by the addition of 1-OMe resulted in a clean formation of 6bf (97% yield, see Scheme 8).

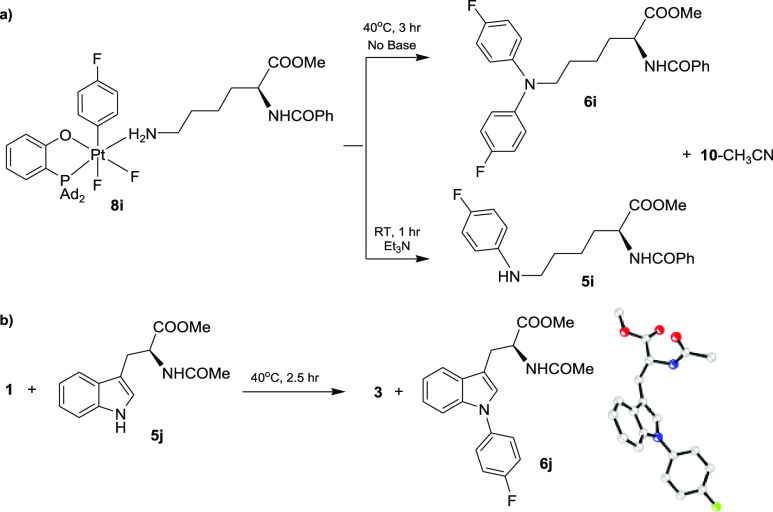

A particularly interesting application of this new chemistry involves N-arylation of amino acid derivatives by (P–O)Pt(IV) aryl complexes. Recently, N-arylation of an amino acid has received a great deal of attention as a new technique for late-stage modification of peptides and proteins.21 In particular, an ε-NH2 arylation of the lysine (Lys) residue was reported in selected olygopeptides using Pd(II) complexes under mild basic conditions.16e In our system, the p-fluorophenyl Pt(IV) complex 8i, bearing a partially protected Lys as a ligand, underwent facile di-N-arylation in the absence of external base additives, at 40 °C, to give 6i as the only product in a 88% yield after 3 h. In the presence of Et3N, the same reaction led to a selective monoarylation of a Lys side chain to give 5i in a 93% yield (Scheme 9a), thus demonstrating an easy-to-control selectivity in mono- and di-N-arylation of amino acid derivatives. Furthermore, the observed reactivity of a secondary amino group, such as in compounds 5, led us to explore the N–H arylation of tryptophan (Trp), which has never been demonstrated under mild base-free conditions.22,23 Satisfyingly, the addition of a Trp derivative 5j to a solution of 1 resulted in a clean formation of 6j in a 91% NMR yield, which was characterized crystallographically (Scheme 9b).

N-Arylation of Amino Acid Derivatives

Unlike the commonly proposed SN2-type reductive elimination of C(sp3)–X bonds from M(IV)–alkyl complexes,1−5,10,11 the aryl C(sp2)–X coupling of complexes 2 and 8 may be expected to occur as a concerted process.12 To confirm the viability of such C–X coupling mechanism in these reactions, we carried out their computational modeling. In our calculations we utilized the density functional theory (DFT) method implemented in the Jaguar program package,24 using the PBE functional25 and LACVP relativistic basis set with two polarization functions. This level of theory was used successfully in previous works dealing with modeling of kinetics of organometallic reactions.8,26 A frequency analysis was performed for all stationary points. In addition, using the method of intrinsic reaction coordinate, reactants, products, and the corresponding transition states were proven to be connected by a single minimal energy reaction path. The solvation Gibbs energies in MeCN for all solutes were found using single-point calculations utilizing the Poisson–Boltzmann continuum solvation model, as implemented in the Jaguar package.24

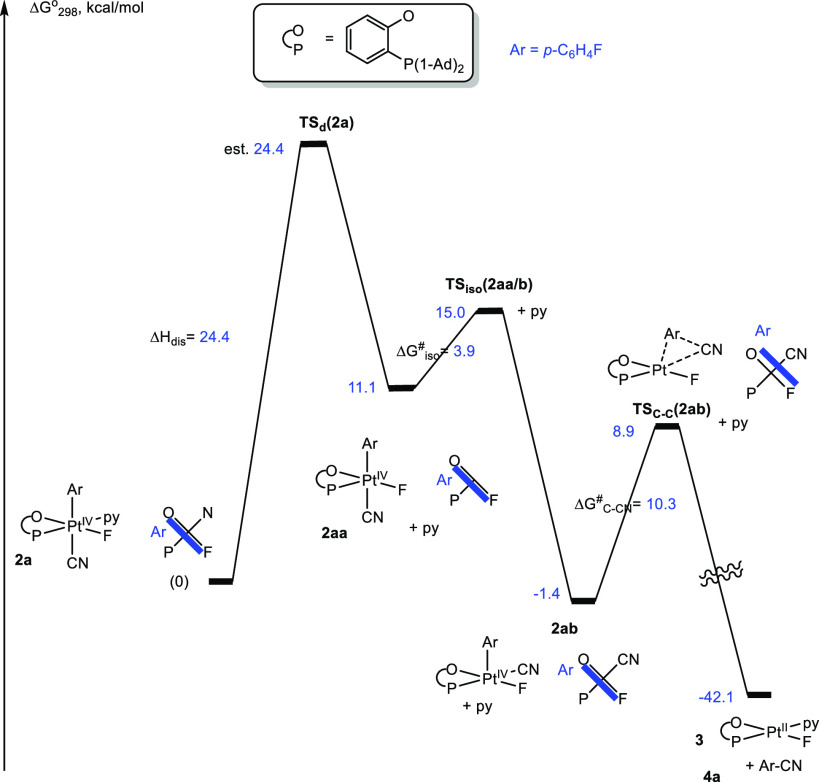

The results of our analysis of elimination of p-FC6H4–CN, 4a, from the aryl Pt(IV) cyano complex 2a are presented in Figures 2 and 3. A concerted C–C coupling at a Pt(IV) center would require a cis arrangement of the aryl and CN ligands, which is not the case for complex 2a. Hence, we considered a three-step reaction sequence (Figure 2) including (a) pyridine ligand loss to form a 5-coordinate transient 2aa (ΔG°298 = 11.1 kcal/mol), (b) its trans-Ar, CN/cis-Ar, CN isomerization leading to 2ab (ΔG°298 = −1.4 kcal/mol) having the Ar and CN ligands in the required cis position, and (c) the Ar–CN coupling of the transient 2ab. Because the transition state TSd(2a) for the pyridine dissociation could not be found, we used the calculated reaction enthalpy for this step, 24.4 kcal/mol, as an upper estimate for its Gibbs activation energy. This approximation suggests that the entropy changes are small when going from 2a to TSd(2a). The resulting 5-coordinate transient 2aa undergoes a low-barrier (ΔG⧧iso(2aa/b) = 3.9 kcal/mol) isomerization to 2ab, which is involved in another low-barrier (ΔG⧧C–CN(2ab) = 10.3 kcal/mol) C–C coupling step leading to product 4a and the Pt(II) pyridine complex 3. Overall, the pyridine dissociation is the rate-limiting step, and our estimate of the activation energy for this step, 24.4 kcal/mol, is reasonably close to the observed reaction Gibbs activation energy of 26.9 kcal/mol.

Reaction Gibbs energy profile for the C–CN bond elimination of p-FC6H4–CN, 4a, from complex 2a in MeCN solution. The energy of TSd(2a) is estimated.

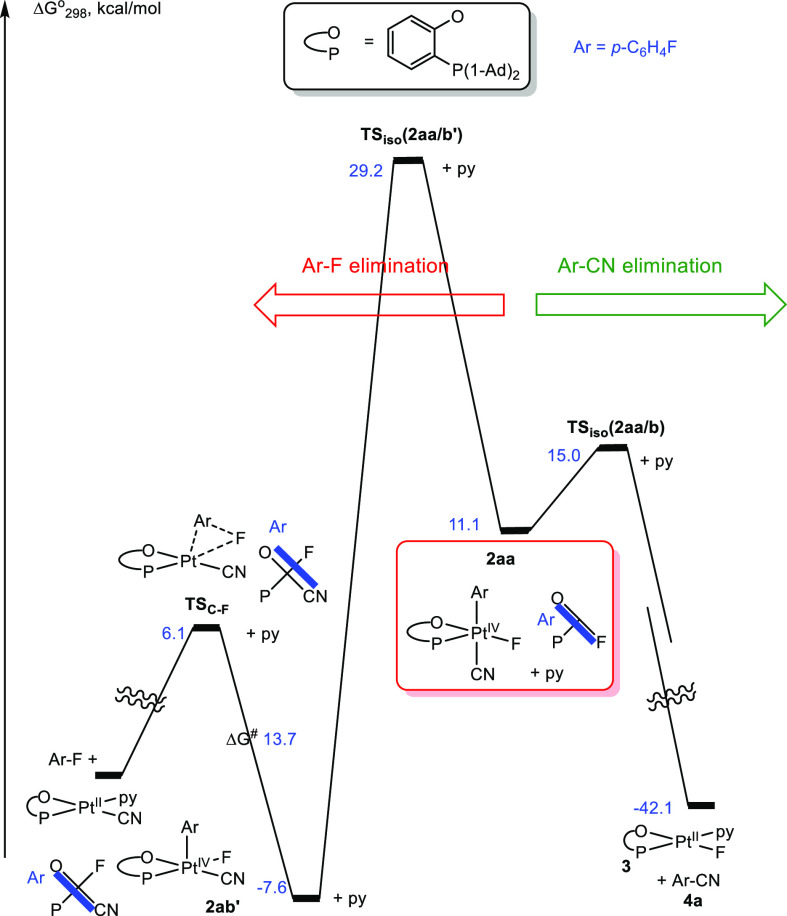

Reaction Gibbs energy profile for two diverging potentially competitive reaction paths of complex 2a in MeCN solution involving five-coordinate intermediate 2aa (see Figure 2): (a) the C–CN bond elimination to form p-FC6H4–CN, 4a (right, see also Figure 2), and (b) the C–F bond elimination to form p-F2C6H4 (left).

Considering another plausible 5-coordinate intermediate, 2ab′ (Figure 3), having the fluoro ligand in place of the cyanide in 2ab, we also checked how facile might be an Ar–F elimination of 2ab′. Notably, 2ab′, featuring the favorable arrangement of the fluoride and aryl ligands, can undergo C–F bond elimination to form 1,4-difluorobenzene with a low 13.7 kcal/mol Gibbs activation energy (Figure 3, left). Most importantly, in addition to being less competitive than the C–C coupling (ΔG⧧C–CN = 10.3 kcal/mol), the isomerization of 2aa to 2ab′ is characterized by a high 29.2 kcal/mol Gibbs activation energy (see also Figure S4 for an alternative isomerization path from 2aa to 2ab′ with 28.9 kcal/mol Gibbs activation energy), thus making the isomer 2ab′ needed for the C–F coupling virtually inaccessible and the C–F coupling noncompetitive. This result is in accord with the lack of the experimental observation of 1,4-difluorobenzene among our reaction products.

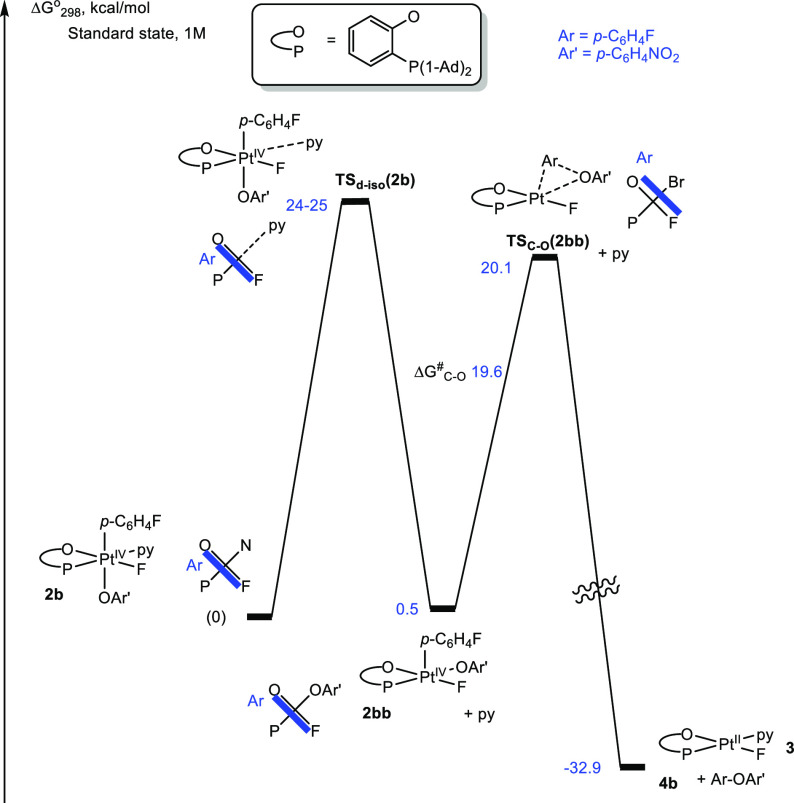

A similar computational analysis of the C–O elimination of the ether product, p-FC6H4–O-p-C6H4NO2, 4b, from the aryl Pt(IV) p-nitrophenoxo complex 2b (Figure 4) shows the absence of any stable 5-coordinate species that would result from pyridine dissociation and would have trans arrangement of the Ar and O-p-C6H4NO2 ligands. Our attempts to locate this structure on the potential energy surface led to its isomer 2bb (ΔG°298 = 0.5 kcal/mol) with a cis arrangement of the Ar and O-p-C6H4NO2 ligands. Hence, the pyridine ligand dissociation is accompanied by the change of the configuration of the Pt(IV) center. The resulting transient 2bb undergoes facile C–O coupling with a Gibbs activation energy of 19.6 kcal/mol.

Reaction Gibbs energy profile for the C–O bond elimination of p-FC6H4–O-p-C6H4NO2, 4b, from complex 2b in MeCN solution. The energy of TSd-iso(2b) is estimated.

Our experimental data for the reaction rate constant, k348 = (4.8 ± 0.3) × 10–5 s–1 (ΔG⧧348 = 27.3 kcal/mol), show that the actual reaction Gibbs activation energy is greater than the calculated 20.1 kcal/mol activation energy for the C–O coupling (Figure 4). Combined with the fact that no transients such as 2bb were observed in the reaction, we presume that dissociation/5-coordinate transient isomerization step TSd-iso(2b) is rate-determining. The activation barrier for this step should be close to that for the reaction involving 2a, 24–25 kcal/mol, which is a reasonably good match to the experimental value discussed.

The reaction Gibbs energy profile for the C–Cl coupling/elimination of p-FC6H4–Cl, 4c, from the aryl Pt(IV) chloro complex 2c (Figure S5) shows great similarity to that for complex 2b (Figure 4). As for 2b, a 5-coordinate transient with trans arrangement of the Ar and Cl ligands that is expected to result from pyridine ligand dissociation step could not be located, and its cis isomer 2cb (ΔG°298 −0.4 kcal/mol), an analogue of 2bb in Figure 4, was the only derived 5-coordinate species that was found. The latter undergoes a facile C–Cl coupling with a Gibbs activation energy of 19.6 kcal/mol. The experimentally determined Gibbs activation energy for the C–Cl coupling, ΔG⧧, is 23.3 kcal/mol. Similar to the case of 2b, no intermediates were observed in this reaction, and we propose that the pyridine dissociation/5-coordinate transient isomerization step is rate-limiting here as well. We consider the expected barrier for this step to be about the same as that for 2a, 24–25 kcal/mol, which is reasonably close to the experimental value of 23.2 kcal/mol.

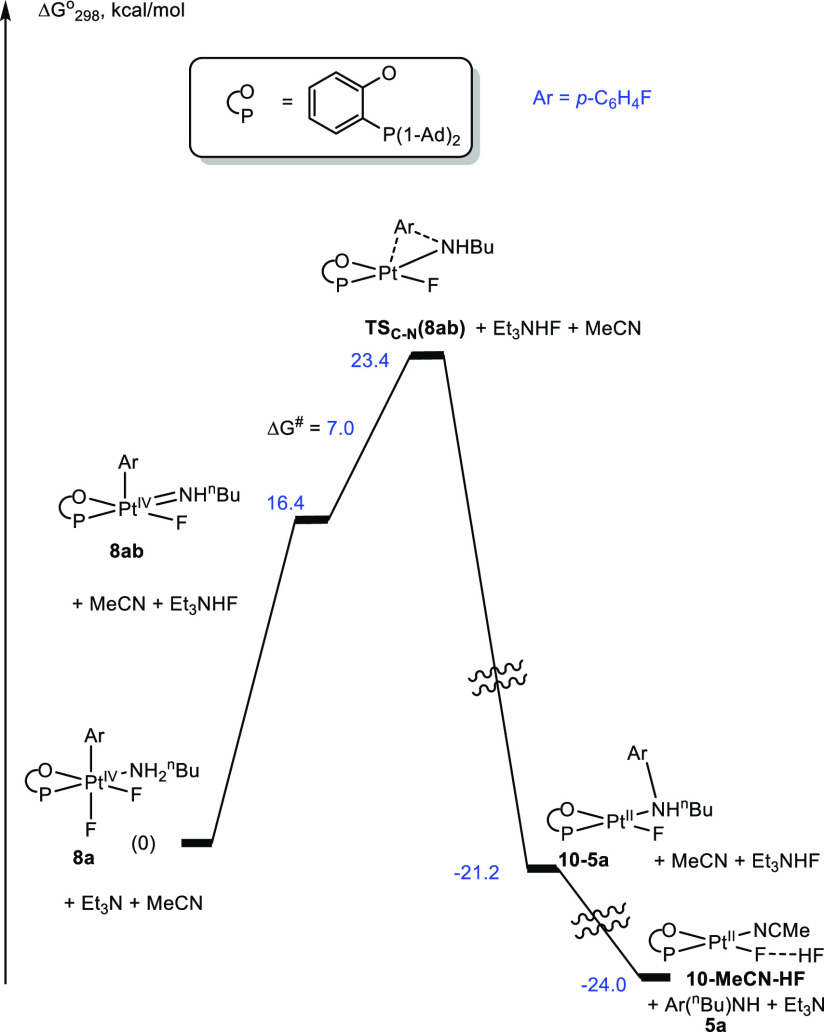

The most mechanistically intriguing, as compared to the C–X bond elimination of 2a–2c (X = C, O, Cl), is the C–N coupling of the aryl Pt(IV) n-butylamine complex 8a leading to either the monoarylamine p-FC6H4–NHnBu, 5a, in the presence of Et3N (Figure 5) or the diarylamine (p-FC6H4)2NnBu, 6a, in the absence of additives (Figures 6, 7, and S6). In 8a, the amine and aryl ligands have the required cis arrangement, but the Gibbs activation energy corresponding to a direct C–N elimination of the ammonium cation p-FC6H4–NH2nBu+ is too high, 33.2 kcal/mol (Figure S7). The most likely reaction mechanism (Figure 5) involves deprotonation of the coordinated amine with Et3N leading overall to HF elimination from 8a to produce a 5-coordinate Pt(IV) amido transient 8ab. This step is endergonic (ΔG°298 = 16.4 kcal/mol), but the subsequent Ar–N coupling is facile with a Gibbs activation energy of only 7.0 kcal/mol.

Reaction Gibbs energy profile for the C–N bond elimination of p-FC6H4–NH-n-Bu, 5a, from complex 8a in the presence of Et3N in MeCN solution.

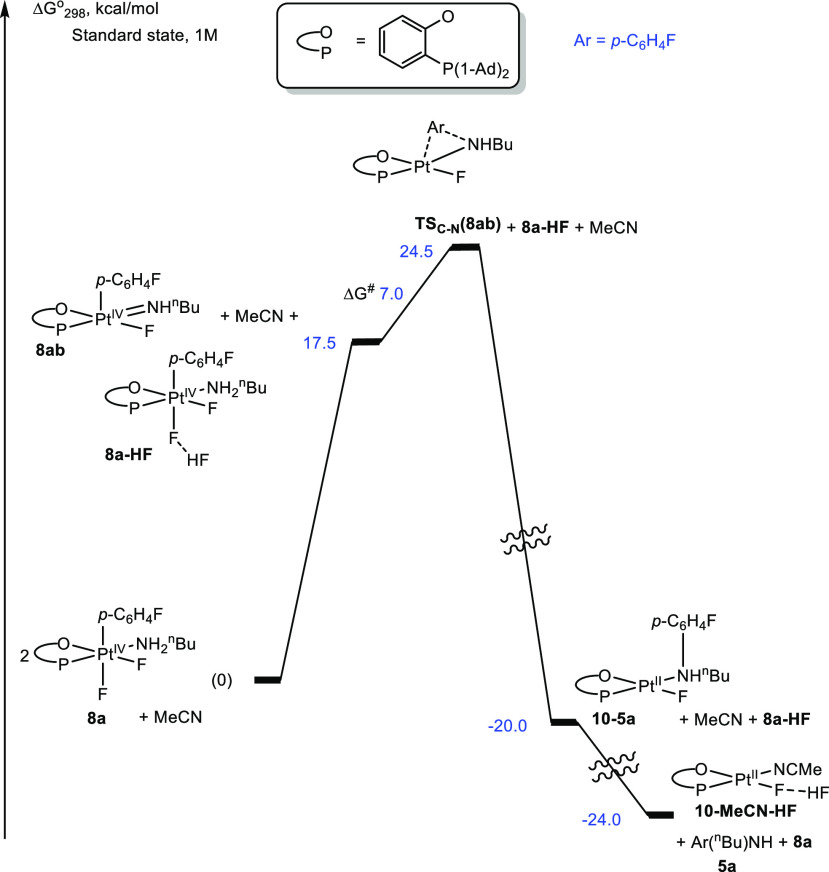

Reaction Gibbs energy profile for the first C–N coupling (first N-arylation) step of complex 8a leading to p-FC6H4–NH-n-Bu, 5a, in the absence of Et3N in MeCN solutions.

Gibbs energy profile for the second C–N coupling (second N-arylation) step of complex 8a leading to (p-FC6H4)2N–n-Bu, 6a, in the absence of Et3N in MeCN solution. The energies of TSd(8a) and TSc(8aa) are estimated.

The corresponding transition state TSC–N(8ab) is the highest point on the reaction energy profile, and its energy, 23.4 kcal/mol, is a reasonable match to the experimentally determined Gibbs activation energy for the Et3N-promoted C–N coupling, 21.9 kcal/mol. The resulting Pt(II) N-arylamine complex 10–5a then can release free amine 5a and form an acetonitrile adduct 10–MeCN after ligand substitution with a MeCN solvent species. According to our calculations, the Pt(II) fluoride complex 10–MeCN can form with HF a robust bifluoride derivative containing, formally, a HF2– ligand. As a result, 10–MeCN is a slightly stronger base, by 1.4 kcal/mol, with respect to HF, as compared to Et3N, such that Et3N can be viewed as an effective base catalyst for the amine monoarylation reaction.

Two consecutive N-arylations of n-butylamine originating from complex 8a to form N,N-diarylamine 6a occur in the absence of Et3N additives (Scheme 6, top). The first N-arylation in the absence (Figure 6) and presence of Et3N (Figure 5) operates by a similar mechanism. In the absence of Et3N, an HF elimination from 8a to produce the 5-coordinate Pt(IV) amido transient 8ab is carried out by second equivalent of 8a, acting as a Brønsted base, to form an 19F NMR-detectable bifluoride complex 8a–HF. Notably, the Pt(IV) fluoro complex 8a is a slightly weaker base than Et3N. As a result, the HF-elimination step leading to 8ab is 1.1 kcal/mol more endergonic in the absence of Et3N, as compared to the reaction in the presence of Et3N (Figure 5). Accordingly, the energy of the transition state TSC–N(8ab) leading to the monoarylamine 5a is now 1.1 kcal/mol higher, 24.5 kcal/mol (Figure 6). Finally, the HF produced in the first arylation step is transferred from 8a–HF to the fluoride ligand of 10–MeCN to form 10–MeCN–HF and to release 8a in a slightly exergonic reaction.

The second N-arylation reaction involves an initial 5a-for-BuNH2 substitution via a dissociative mechanism to form 8ac (Figure 7), which is an N-(n-butyl)-p-fluoroaniline analogue of the n-butylamine complex 8a. Remarkably, N-(n-butyl)-p-fluoroaniline 5a is a worse ligand than n-butylamine, and the formation of 8ac is a thermodynamically uphill process. However, the energy penalty for this step is diminished significantly because of the ability of the liberated n-butylamine to react exergonically with complex 10–MeCN–HF by displacing its MeCN ligand via the transition state TSLS (Figures 7 and S6).20

A subsequent base-mediated reaction of 8ac produces the five-coordinate Pt(IV) amido species featuring a bifluoride ligand, 8ad. The HF transfer here may be mediated by 8a. Finally, the platinum(IV) amido species 8ad undergoes aryl–N reductive elimination with a low 4.8 kcal/mol barrier (TSC–N(8ad–HF), Figure 7) to form the Pt(II) diarylamine complex 10–6a–HF. The diarylamine 6a is then liberated as a result of a ligand substitution with MeCN, along with the formation of 10–MeCN–HF.

The highest energy points on the diagrams in Figures 6 and 7 corresponding to the first (Figure 6) and second (Figure 7) N-arylation reactions are 24.5 and 26.1 kcal/mol, respectively. Both values are reasonably close to the experimental Gibbs energy of activation for the overall N,N-diarylation reaction, 23.5 kcal/mol. The highest point for the second N-arylation, 26.1 kcal/mol, corresponding to n-butylamine ligand dissociation from complex 8a, is approximated using the enthalpy change for the ligand dissociation and is likely overestimated. Finally, considering the whole reaction sequence involved in the second N-arylation (Figure 7), it is important to note that the substitution of n-butylamine ligand in 8a with the incoming arylamine 5a and the formation of 8ac determine the rate of the whole N-arylation with either TSd(8a) or TSLS as the highest energy point on the reaction energy profile.

The mechanistic analysis presented in Figures 5–7 allows us to account for the remarkable effect of Et3N additives on the C–N coupling reactivity of n-butylamine complex 8a. The complex produces 0.5 equiv of N,N-diarylamine 6a when no additives are present, whereas Et3N additives trigger this reactivity so that 8a selectively forms 1 equiv of N-monoarylamine 5a (Scheme 6). As follows from the comparison of Figures 5 and 6, because it is a stronger base than 8a, Et3N accelerates the first C–N coupling step involving the coordinated n-butylamine and leading to 5a. At the same time, Et3N cannot accelerate the second intermolecular N-arylation leading to 6a because the rate-determining step for the second N-arylation, the displacement of n-BuNH2 from 8a with N-arylamine 5a, is unaffected by free Et3N. This mechanistic difference between the first and second N-arylation reactions results in the selective N-monoarylation of n-butylamine ligand when Et3N is present.

Notably, the N-arylation reactivity of the electron-richer p-methoxyphenyl complex 8f is similar to that of the p-fluorophenyl complex 8a. For 8f, the N,N-diarylation of the coordinated n-butylamine to produce 6f (Scheme 7, right) is also facile in the absence of Et3N, but, when Et3N is available, only N-monoarylamine 5f forms. However, the electron-poorer 3,5-difluorophenyl Pt(IV) complex 8g produces exclusively N-monoarylamine 5g (Scheme 7, left) in both the absence and the presence of Et3N in the reaction mixture; the N,N-diarylation of coordinated n-butylamine is not observed.

This difference in the behavior of 8a, 8g, and 8f can be accounted for by using the reaction mechanism proposed for the second N-arylation (Figure 7). According to our DFT calculations, the dissociation of coordinated n-butylamine is about as fast for 8f as it is for 8a with dissociation enthalpies of 26.0 versus 26.1 kcal/mol, respectively (Figure S8). In turn, for the electron-poorer complex 8g, the ligand dissociation is predicted to be more endergonic, 26.9 kcal/mol. In support of the notion of the increasing Pt(IV)–(NH2nBu) bond strength in the series of complexes 8f, 8a, and 8g, which is related to the height of the amine dissociation barrier, two qualitative bond strength descriptors, the natural charge on the Pt(IV) atom and the natural localized orbital natural population analysis (NLMO/NPA) bond order for the Pt(IV)–N bond, were calculated. Both parameters were found to increase in the order 8f (electron-richest) < 8a < 8g (electron-poorest), thus suggesting a trend of the increasing Pt(IV)–N bond strength (Table 1).

| complex | natural charge on Pt(IV) atom | NLMO/NPA bond order for the Pt(IV)–N bond |

|---|---|---|

| 8a | 1.113 | 0.1654 |

| 8f | 1.110 | 0.1649 |

| 8g | 1.120 | 0.1662 |

To summarize, on the basis of the results above, in the absence of any better estimates for the Gibbs activation energy values for the n-BuNH2 ligand dissociation step, we postulate that the slower rate of n-butylamine ligand substitution in 8g leading to the key intermediate 8gc is responsible for the reactivity change and the lack of the N,N-diarylated product.

In conclusion, we reported a series of facile aryl C(sp2)–X bond elimination reactions (X = Cl, CN, OAr, N(Alk)R) at a Pt(IV) center using a series of Pt(IV) aryl complexes of the same structural type. These reactions include C(sp2)–N coupling involving the Pt(IV)-coordinated aryl and primary alkylamine ligands. A combination of electronic properties and steric bulk of the ancillary 2-[bis(adamant-1-yl)phosphino]phenoxide ligand (P–O) appears to be an important factor governing this facile C–X bond-making chemistry. Interestingly, the isolated (P–O)PtIVF2(Ar)(NH2Alk) complexes undergo an unexpectedly facile double aryl C(sp2)–N coupling under mild conditions, giving diarylamines (Ar)2NAlk in high yields (Ar = p-FC6H4, p-MeOC6H4). With the sterically demanding t-BuNH2 or with the electron-poorer aryl ligand 3,5-F2C6H3, only monoarylamines ArNHAlk are isolated under the same conditions. There results demonstrate the fine balance in the reactivity between the initially coordinated AlkNH2 ligand and the product ArNHAlk resulting from the first C(sp2)–N coupling step. Importantly, in the presence of a base, such as Et3N, all studied Pt(IV) complexes quantitatively give the corresponding monoarylamine ArNHAlk products within 1 h at room temperature. These findings allowed for a one-pot preparation of unsymmetrical diarylamines (Ar1)(Ar2)NAlk, all under mild conditions. The new chemistry was also successfully applied in the unprecedented arylation of two partially protected amino acids, resulting in a selective high-yielding single (with an added external base) or double (without external base additives) ε-NH2-arylation of a lysine derivative and a high-yielding NH-arylation of a tryptophan derivative. Further studies on the reactivity of Pt(IV) complexes in the arylation of biologically relevant substrates are underway in our laboratories.

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/jacs.0c09452.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Dedicated to the memory of Professor Kilian Muñiz. This research was supported by a grant from the United States– Israel Binational Science Foundation (BSF), Jerusalem, Israel, and Joint NSFC–ISF Research Grant (2572/17). We are grateful to Prof. Guosheng Liu (Shanghai Institute of Organic Chemistry) for a valuable discussion. We also thank Dr. Sophia Lipstman for performing the X-ray crystallographic analysis.

See Supporting Information for details.

The 21% yield is calculated based on the amount of the starting material; that corresponds to 42% if the aryl group balance is considered.

The eliminated amines 4-FC6H4NHAlk as well as RNH2, along with CH3CN, are involved in coordination with Pt(II), as demonstrated by an example of an isolated adduct 10–5c (Scheme 6). The formation of a mixture of the derived Pt(II) fluoro complexes 10–L is supported by the 19F NMR spectroscopy. The fluoro complexes 10–L may also exist as bifluorides (P–O)Pt(L)(F–HF), as evidenced by occasional observation of a signal at ∼ −180 ppm in the 19F NMR spectra. To liberate the free amines and obtain more accurate integration ratios, reaction mixtures were treated with excess pyridine, resulting in the formation of a Pt(II) pyridine adduct 3.