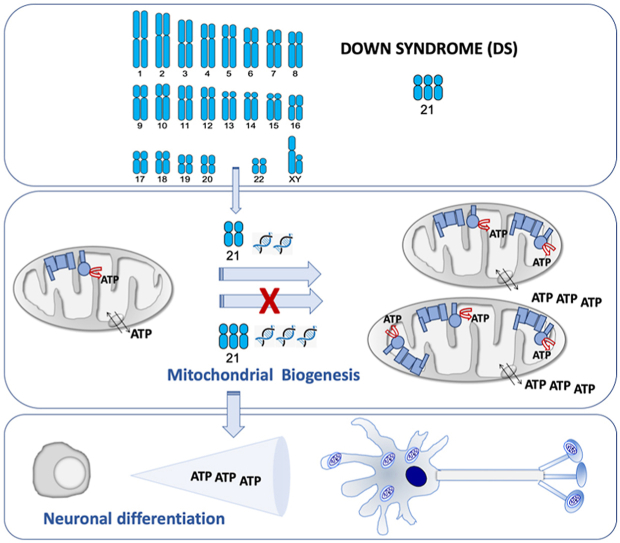

Down syndrome is the most common genomic disorder of intellectual disability and is caused by trisomy of chromosome 21. Several genes in this chromosome repress mitochondrial biogenesis. The goal of this study was to evaluate whether early overexpression of these genes may cause a prenatal impairment of oxidative phosphorylation negatively affecting neurogenesis. Reduction in the mitochondrial energy production and a lower mitochondrial function have been reported in diverse tissues or cell types, and also at any age, including early fetuses, suggesting that a defect in oxidative phosphorylation is an early and general event in Down syndrome individuals. Moreover, many of the medical conditions associated with Down syndrome are also frequently found in patients with oxidative phosphorylation disease. Several drugs that enhance mitochondrial biogenesis are nowadays available and some of them have been already tested in mouse models of Down syndrome restoring neurogenesis and cognitive defects. Because neurogenesis relies on a correct mitochondrial function and critical periods of brain development occur mainly in the prenatal and early neonatal stages, therapeutic approaches intended to improve oxidative phosphorylation should be provided in these periods.

•

Several chromosome 21-encoded proteins repress mitochondrial biogenesis.

•These proteins are overexpressed in fetal brains of Down syndrome (DS) individuals.

•Oxidative phosphorylation function is essential for neurogenesis.

•Upregulation of these proteins adversely impact on neurogenesis.

•Prenatal therapy with drugs inhibiting these proteins would increase DS neurogenesis.

Down syndrome (DS) is a multigene, multisystem disorder [1]. A partial or complete third copy of chromosome 21 (Hsa21), trisomy 21 (T21), is the major cause of DS. This condition is associated with intellectual disability, but other medical conditions, such as visual problems and hearing deficits, seizures, dementia, cardiac and muscle complications and gastrointestinal anomalies are also common in DS individuals [2,3].

Abnormalities in virtually every organ system are routinely treated in DS [4]. Intellectual disability is a key aspect of DS [4]. DS individuals show smaller brain volumes and reduced cortical surface area [1]. The brain of DS individuals exhibits a decline in proliferation and neuronal differentiation capacities of neural progenitor cells (NPCs) and an increased cell death. This deficient neurogenesis can already be observed in the fetal period [[5], [6], [7]]. To improve cognitive capabilities, active care programs using enriched environments are one of the most successful therapeutic interventions. However, results are limited and temporary [8].

The oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS) system is the main energy provider to power activity of mature neurons [9]. For this reason, the central nervous system is one of the most affected tissues in OXPHOS disorders [10].

The modulation of maternal oxygenation in mice affects the fetal brain oxygen levels. Compared with normoxic brains, fetal brain volume of hypoxia-treated embryos was reduced whereas hyperoxia provoked a significant increase in brain volume [11]. Oxygen is mainly consumed by the OXPHOS system [12]. These observations suggest that OXPHOS function is also fundamental for brain development and the neurogenic process during prenatal development [13,14]. This biochemical pathway is required for neuronal differentiation [15,16]. In fact, pathological mutations in mouse or human OXPHOS-related genes impaired neuronal differentiation [[17], [18], [19]]. Confirming this effect, we have recently shown that neuronal differentiation of human cells overexpressing a mitochondrial ribosomal protein S12 (MRPS12) mutant gene was significantly reduced [20]. Moreover, the ribosomal antibiotic linezolid, that inhibits mitochondrial translation and decreases OXPHOS function, and cyanide, an OXPHOS poison, decreased neuronal differentiation of human cells [20,21].

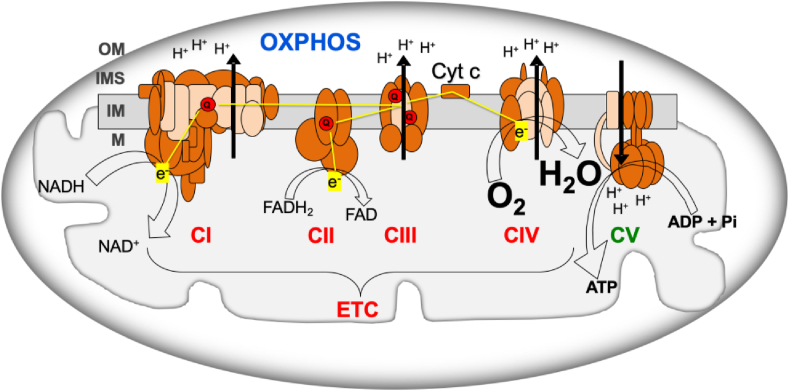

OXPHOS system consists of mitochondrial inner membrane electron transport chain (ETC) and ATP synthase (OXPHOS complex V, CV) (Fig. 1). ETC includes respiratory complexes I to IV (CI - CIV), cytochrome c and coenzyme Q (Q). Most of the mitochondrial proteins, including all the proteins required for mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) replication, transcription and translation; assembly proteins of OXPHOS complexes; and most of the structural subunits of the OXPHOS complexes are coded in the nuclear chromosomes (nDNA). However, 13 OXPHOS subunits are mtDNA-encoded, along with the transfer and ribosomal RNAs (tRNAs and rRNAs) needed for their production. Electrons from the nutrients reduce flavin and nicotinamide coenzymes (FAD/FADH2 and NAD+/NADH) and, through CI and CII, reduce Q (ubiquinone/ubiquinol). Electrons from ubiquinol go through CIII, cytochrome c and CIV to reduce oxygen to water. The electron flow through the ETC determines the oxygen consumption and the mitochondrial inner membrane potential generated by the proton pumping from the mitochondrial matrix into the intermembrane space.

Oxidative phosphorylation system (OXPHOS). ADP, adenosine diphosphate; ATP, adenosine triphosphate; Cyt c, cytochrome c; CI-IV, respiratory complexes I-IV; CV, ATP synthase; ETC, electron transport chain; e−, electrons; FADH2/FAD, reduced and oxidized flavin adenine dinucleotide; H2O, water; H+, protons; IM, mitochondrial inner membrane; IMS, intermembrane space; M, mitochondrial matrix; NADH/NAD+, reduced and oxidized nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide; OM, mitochondrial outer membrane; O2, oxygen; Pi, phosphate; Q, coenzyme Q. Brown and pink colors are used for nDNA- and mtDNA-encoded subunits, respectively. Yellow lines, electron flow. Black arrows, proton pumping. (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the Web version of this article.)

There are several mouse models of DS [[22], [23], [24]], and some of them have been used to study neurogenesis and several mitochondrial parameters under this condition. It was published that the astrocytes of Ts1Cje mice, carriers of a trisomic segment that extends from Sod1 to Znf295 genes, showed a decrease in mitochondrial inner membrane potential and lower levels of ATP. The cerebral cortex of three-month-old Ts1Cje mice also had lower levels of ATP [25]. In Ts3Yah mice, which carry a tandem duplication of the Hspa13-App interval, there was a decrease in mRNAs of genes related to the OXPHOS system, in those related to mitochondrial biogenesis and in the amount of mtDNA in skeletal muscle [26]. The oxygen consumption with CI substrates was decreased in cerebral mitochondria of Ts65Dn mice, that harbor a trisomic segment between the App and Znf295 genes [27]. The levels of the p.MT-CO2 subunit from CIV were reduced in the soleus muscle of six-month-old Ts65Dn mice [28]. The oxygen consumption, CI and CIV activities, amount of ATP and mtDNA levels were shown decreased in NPCs of Ts65Dn mice. The impairment of the OXPHOS system was accompanied by a decrease in neuronal proliferation and differentiation capacity that has been suggested to be responsible for the reduced neuronal density found in the Ts65Dn mouse [[29], [30], [31]].

Several studies using differentiated cells from T21 human induced pluripotent stem cells (hiPSCs) showed that these models reflect the molecular and cellular phenotypes observed in primary cells and in individuals with DS [32]. T21 hiPSCs-derived neurons showed decreased mitochondrial inner membrane potential and increased production of amyloid peptide [33]. A reduction in mitochondrial inner membrane potential was also informed in lymphocytes and lymphoblastic cell lines from DS individuals [34,35], and also in neurons, astrocytes and fibroblasts of DS fetuses from 14 to 22 weeks of gestation [[36], [37], [38], [39], [40]]. A decrease in oxygen consumption was reported in fibroblasts and lymphocytes of DS individuals and fibroblasts of DS fetuses from 14 to 22 weeks of gestation [37,39,[41], [42], [43], [44], [45]]. The activity of ETC complexes was found decreased in fibroblasts, lymphocytes and platelets of DS individuals and fibroblasts of DS fetuses from 14 to 22 weeks of gestation [37,41,[43], [44], [45], [46], [47]]. The quantity of protein subunits for OXPHOS complexes was also reduced in brain, cerebellum and fibroblasts of DS adults or DS fetuses from 14 to 19 weeks of gestation [41,[48], [49], [50], [51]]. A lower Q quantity was reported in lymphocytes, platelets and plasma of DS individuals [52,53]. mRNA levels of a number of genes coding subunits of the OXPHOS complexes were decreased in T21 hiPSCs [54]. Supporting these data, a reduction in mRNA levels of several subunits of OXPHOS complexes was reported in DS cerebellum and fibroblasts [55,56]. Very interestingly, the down-regulation of genes for all OXPHOS complexes was also found in heart, fibroblasts and amniocytes of DS fetuses from 8 to 22 weeks of gestation [43,51,57,58]. This decline in mRNA levels was accompanied by a lower transcription of mtDNA-encoded genes and by a lower amount of mtDNA in brain from individuals with DS and Alzheimer disease (DSAD) and in DS fetuses of 22 weeks of gestation [59,60]. The levels of gene transcripts encoded in mtDNA were also found reduced in differentiated neurons from NPCs of DS individuals. This fact was accompanied by a reduced proliferative rate and a deviation of neuronal differentiation towards astrocytes [61].

All these modifications give place to a reduction in the mitochondrial energy production and a lower mitochondrial function [35,38,39,41,44,45,62,63]. As it can be noted from all these publications, OXPHOS defects were reported in distinct species, diverse tissues or cell types, and also at any age, including early fetuses. Therefore, it can be deduced that this defect is not a side effect but an early and general event in DS individuals. Moreover, many of the medical conditions associated with DS are also frequently found in patients with OXPHOS disease [64]. Thus, ‘red-flag’ features, which warrant the initiation of a baseline diagnostic evaluation for mitochondrial disease [65,66], such as epilepsia, intestinal dysmotility and hypotonia are also observed in DS individuals [2,3]. A multitude of other nonspecific symptoms that frequently occur in patients with mitochondrial disease [65,66], such as short stature, hearing loss, hypothyroidism and autism spectrum disorder (ASD) are also found in DS individuals [2,3]. Interestingly, similar to DS, ASD is a neurodevelopmental condition and the affectation of neurogenesis begins in the prenatal stage [67]. Moreover, an OXPHOS dysfunction is also found in ASD [68,69]. For all the aforementioned reasons, DS can be considered as an OXPHOS disorder.

The overexpression of genes from Hsa21 is responsible for the DS pathogenesis. Some of these genes play a role in the expression of other genes and many of them are involved in the OXPHOS function. One of these genes is the amyloid precursor protein (APP) gene that is located in the chromosomal band 21q21.3 (Fig. 2A). This gene is overexpressed in different cell types from DS individuals [70,71]. While iPSCs had transcriptome profiles comparable to that of normal fetal brain development [61], T21 iPSCs had a marked upregulation of APP expression [61,72,73]. Moreover, its expression was also upregulated in NPCs, astrocytes and neurons derived from T21 hiPSCs [71,74]. Increased APP, and its carboxy-terminal fragment 99 (CTF99), levels were found in primary DS fetal brain cultures [36]. Increased APP mRNA and protein levels have been also detected in brains of fetuses with DS [[75], [76], [77], [78], [79]]. Moreover, amyloid beta (Aβ) was detected in fetuses with DS, but not in age-matched controls [80]. Increased CTF levels were also found in the brains of fetuses with DS [81]. The APP protein can associate with components of the mitochondrial protein translocation machinery and prevent the import of mitochondrial proteins, including nDNA-encoded OXPHOS subunits. Additionally, the APP-derived peptides, such as Aβ, amyloid precursor protein intracellular domain (AICD), and CTF99 can be present in mitochondria, interact with OXPHOS components and mtDNA and have detrimental consequences on bioenergetics function [82,83].

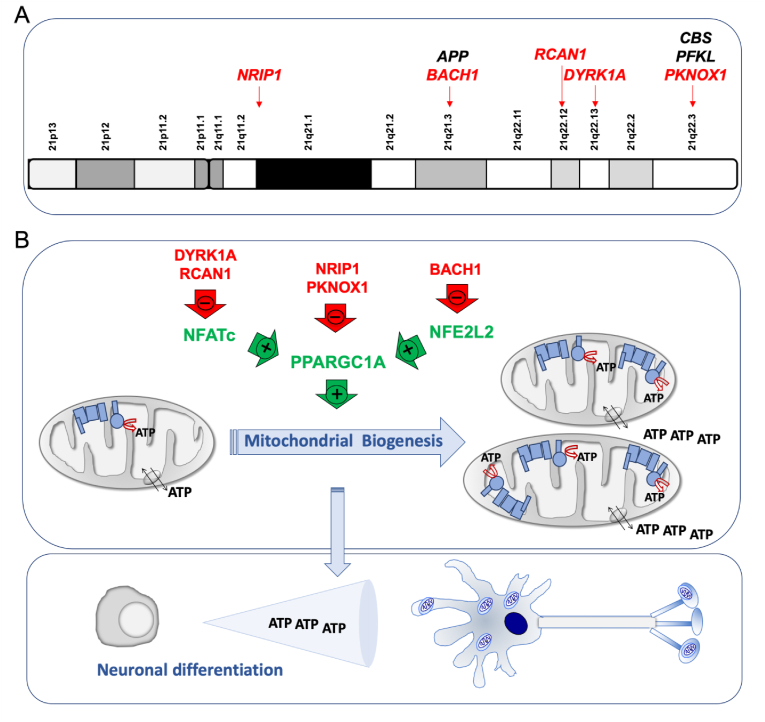

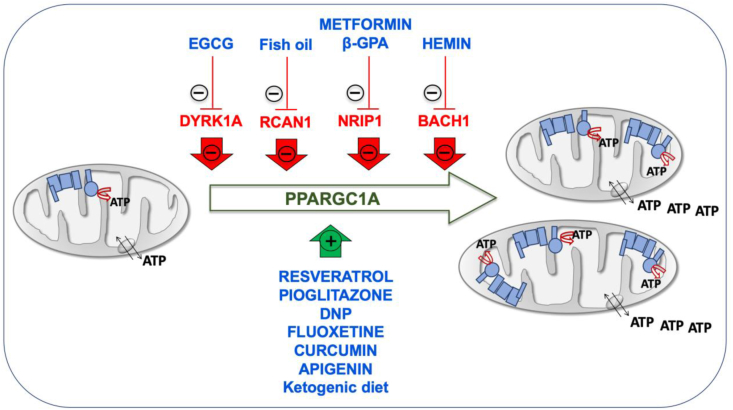

Chromosome 21 genes that repress mitochondrial biogenesis. A) Chromosome 21 location of genes that affect the oxidative phosphorylation function. Some of them, indirectly, through a negative effect on mitochondrial biogenesis (red color). B) Chromosome 21-endoced proteins that block mitochondrial biogenesis. Mitochondrial biogenesis leads to an overall increase in ATP synthesis. Neurogenesis requires high amount of energy. (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the Web version of this article.)

The cystathionine β synthase (CBS) gene is located in the 21q22.3 chromosomal band (Fig. 2A). This enzyme is responsible for the production of the gaseous transmitter hydrogen sulfide (H2S). An increased expression of CBS in many cells and tissues, including the brain, and H2S overproduction are well documented in DS individuals [71,[84], [85], [86], [87], [88], [89], [90], [91], [92]]. Human fetal brains from DS individuals showed increased CBS mRNA levels [78]. It was shown that a chronic exposure of pregnant wildtype animals to inhaled H2S produced significant neurodevelopmental alterations. This compound is an inhibitor of the respiratory CIV [92].

The liver type phosphofructokinase (PFK) gene, located in the chromosomal band 21q22.3 (Fig. 2A), is overexpressed in different cell types and the brain of DS individuals [70,74,88,91]. Its enzyme activity was shown increased in erythrocytes and fibroblasts from DS individuals [[93], [94], [95]]. PFK overexpression negatively regulated neurogenesis from NSCs and inhibited their neuronal differentiation [96]. PFK could play a key role in regulating the metabolic balance between glycolysis and OXPHOS [97].

The dual specificity tyrosine phosphorylation regulated kinase 1 A (DYRK1A) gene coded in the chromosomal band 21q22.13 (Fig. 2A) is overexpressed in different cell types [[70], [71], [72],74,79,98,99], adult brains [88,91,[100], [101], [102], [103]] and fetal brains of DS individuals [78,104,105]. An increase of DYRK1A protein and activity was found in NPCs derived of T21 hiPSCs obtained from fetal fibroblasts [6]. DYRK1A overexpression reduced the nuclear factor of activated T-cells (NFATc) activity (Fig. 2B) [43,106]. NFATc exerts a positive effect on the promoter of the peroxisome proliferator activated receptor gamma coactivator 1 alpha (PGC-1α or PPARGC1A) gene [107], which is a key modulator of mitochondrial biogenesis and OXPHOS function [108]. Therefore, high DYRK1A levels might reduce mitochondrial biogenesis.

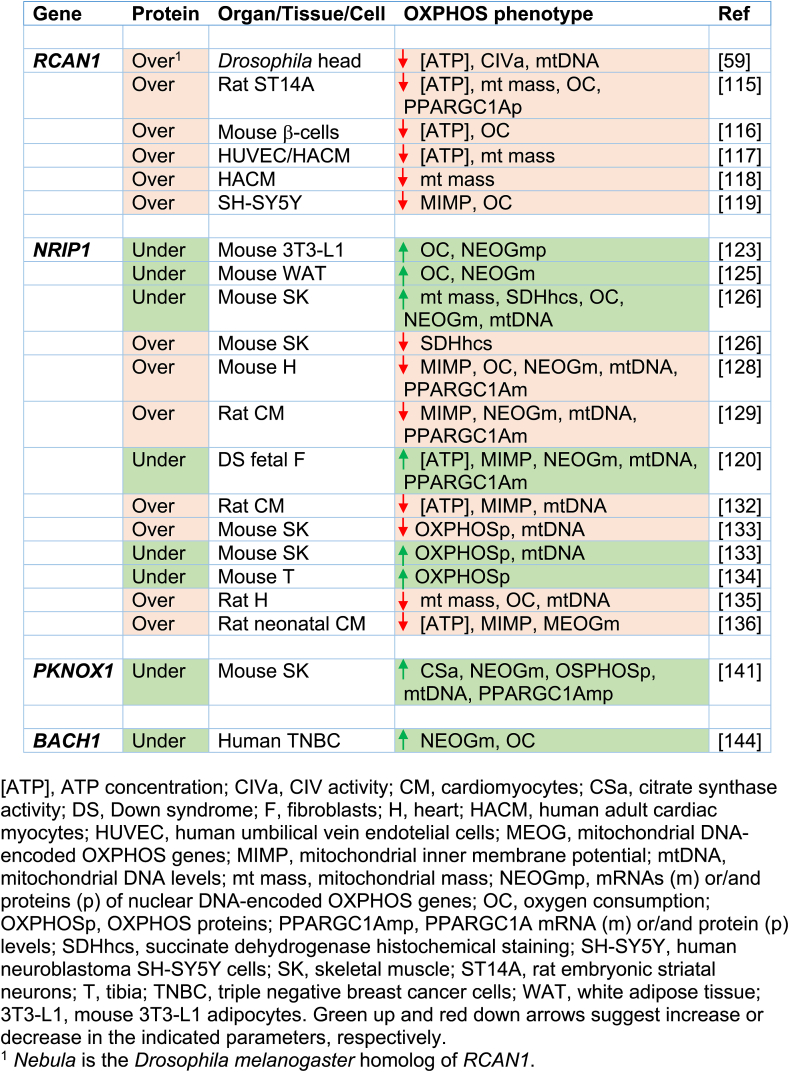

The regulator of calcineurin 1 (RCAN1) gene, located in the chromosomal band 21q22.12 (Fig. 2A), is overexpressed in different cell types and the brain of DS individuals [70,72,88,99]. It is also overexpressed in different DS fetal cells and tissues, such as cultured amniocytes and chorionic villus cells [109,110], fibroblasts [111], liver and kidney [112], and brain [113]. Moreover, neural cells derived from T21 hiPSCs obtained from amniotic fluid stem cells overexpressed RCAN1 [114]. In Drosophila melanogaster, the overexpression of the RCAN1 homolog gene, nebula, reduced CIV activity and mitochondrial DNA content [59]. In embryonic rat striatal neurons ST14A, Rcan1 overexpression leaded to a reduction in mitochondrial mass and oxygen consumption rate [115]. The β-cells of mice overexpressing Rcan1 displayed reduced OXPHOS function [116]. In human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVEC) and cardiomyocytes, RCAN1 overexpression decreased mitochondrial mass [117,118]. In human neuroblastoma SH-SY5Y cells overexpressing RCAN1, oxygen consumption rate was decreased [119]. In addition, RCAN1 overexpression reduced NFATc activity (Fig. 2B and Table 1) [106].

The nuclear receptor interacting protein 1 (NRIP1) gene, which is located in 21q11.2-q21.1 chromosomal band (Fig. 2A), codes for a transcriptional corepressor protein. This gene is overexpressed in different cell types from DS individuals [70,71]. NRIP1 overexpression has been documented in fetal brains and fibroblasts of DS individuals [79,120,121]. It has been shown that Nrip1 levels affect OXPHOS function and mitochondrial biogenesis in different cells and tissues of mice and rats [[122], [123], [124], [125], [126], [127], [128], [129], [130], [131], [132], [133], [134], [135], [136], [137]]. A bias towards OXPHOS in human embryonic stem cells (hESCs) is consistent with increased PPARGC1A and decreased NRIP1 expression [138]. The NRIP1 overexpression in DS fetal fibroblasts represses PPARGC1A and decreases mRNA levels of many OXPHOS-related genes (Fig. 2B and Table 1) [120].

The PBX/knotted 1 homeobox 1 (PKNOX1) gene, located in the chromosomal band 21q22.3 (Fig. 2A), is overexpressed in different cell types from DS individuals [70], and fetal brain and fibroblasts of DS individuals [139,140]. This gene codes for a homeodomain transcription factor. Its muscle-specific ablation resulted in increased expression of ETC subunits, higher enzyme activity, and elevated PPARGC1A expression (Fig. 2B and Table 1) [141].

The BTB domain and CNC homolog 1 (BACH1) gene is located in 21q21.3 chromosomal band (Fig. 2A). This gene is overexpressed in different cell types from DS individuals [70,71,79,142]. It is also overexpressed in DS adult and fetal brain [88,91,143]. BACH1, a haem-binding transcription factor, binds to promoter regions of ETC genes and negatively regulates their transcription, thus reducing mitochondrial respiration [144]. On the contrary, the loss of BACH1 promotes mitochondrial respiration [144]. BACH1 is also a repressor of nuclear-erythroid-derived 2-like 2 (NRF2 or NFE2L2)-induced genes. NFE2L2 displaces BACH1 and upregulates a battery of genes. The PPARGC1A promoter contains NFE2L2 consensus sequences [145]. Therefore, BACH1 negatively regulates mitochondrial biogenesis (Fig. 2B and Table 1).

These observations suggest that several Hsa21 genes negatively regulate the PPARGC1A expression and/or activity [146], as shown in second trimester amniocytes derived from humans with DS [79]. This PPARGC1A downregulation would reduce mitochondrial biogenesis and lead to an OXPHOS defect.

Critical periods of brain development, including neurogenesis and synapse formation, occur mainly in the prenatal and early neonatal stages. As already indicated, permanent neuromorphological alterations originate during fetal life in DS. Thus, this may be the period to positively impact neurogenesis and significantly improve the postnatal cognitive outcome in DS [4,29,32,147,148].

It has been shown that the activation of PPARGC1A and mitochondrial biogenesis protects against prenatal hypoxic-ischemic brain injury [149]. Similar therapies targeting mitochondria have shown to be beneficial in the treatment of DS phenotypes [[150], [151], [152]]. In the same way, the inhibition of overexpressed proteins in DS that reduce OXPHOS function, such as CBS, or mitochondrial biogenesis, such as DYRK1A, might be tested as a potential early therapy [153,154].

It was previously mentioned that PFK knockdown enhanced neuronal differentiation of NSCs and increased neurogenesis in the dentate gyrus of the mouse hippocampus [96]. It has been recently reported that tryptolinamide, a PFK inhibitor, activated mitochondrial respiration and rescued the defect in neuronal differentiation of iPSCs carrying mutant mtDNAs [97].

The promotion of mitochondrial biogenesis is an interesting therapeutic approach. Many drugs, such as epigallocatechin-3-gallate (EGCG), metformin, resveratrol, pioglitazone, β-guanadinopropionic acid (β-GPA) and 2,4-dinitrophenol (DNP) increase the PPARGC1A levels [30,39,146,155,156]. EGCG is a DYRK1A inhibitor and induces mitochondrial biogenesis (Fig. 3) [[157], [158], [159]]. This compound stimulated OXPHOS function in fibroblasts and lymphoblasts of DS individuals [44]. EGCG reversed the mitochondrial energetic deficit and rescued the altered neurogenesis of NPCs from a mouse model of DS or from T21 hiPSCs [6,30]. EGCG improved neurogenesis after ischemic stroke in adult mice [160]. Moreover, neonatal or prenatal treatment with EGCG restored neurogenesis and cognitive defects in mouse models of DS [161,162]. A mix of EGCG and omega-3 fatty acids restored ETC activity in lymphocytes from a DS child [163].

Inducers of mitochondrial biogenesis. Chromosome 21-encoded proteins that repress mitochondrial biogenesis are shown in red color. PPARGC1A, one of the main factors involved in mitochondrial biogenesis is represented in green color. Drugs enhancing mitochondrial biogenesis are indicated in blue color. (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the Web version of this article.)

Omega-3 fatty acids eicosapentaenoic (EPA) and docosahexaenoic (DHA) increased the Ppargc1a expression and mitochondrial biogenesis in the mouse C2C12 myoblast cell line [164]. Omega-3 containing fish oil supplementation starting at conception led to a reduction in hippocampal Rcan1 mRNA and protein levels in 1.5-month-old mice [165]. The prenatal administration of the omega-3 alpha-linolenic acid, that also increase PPARGC1A expression and mitochondrial biogenesis in fat of mice [166,167] and in human SH-SY5Y cells [168], reduced neuromorphological and cognitive alterations in Ts65Dn mice [169]. Alpha-linolenic acid is required in fetal stages of brain development in mice [170].

In mouse C2C12 cells, metformin downregulated NRIP1 and augmented the Ppargc1a levels (Fig. 3) [171]. Metformin also induced mitochondrial biogenesis in human aortic endothelial cells [172], stimulated OXPHOS function in fibroblasts of DS individuals [39], and improved neurogenesis of human bone marrow-mesenchymal stem cells [173]. β-GPA feeding led to marked reductions in both the protein content and mRNA expression of Nrip1 in fast-twitch rat triceps muscles and increased mitochondrial proteins, such as COXI, COXIV, and CS (Fig. 3) [127]. β-GPA treatment increased the mtDNA copy number in the cortex and ventral midbrain of mice, as well as the expression of several key metabolic enzyme indicators of mitochondria proliferation and the activation of Nfe2l2 signaling cascade [174].

Also related to an Hsa21 gene involved in mitochondrial biogenesis, hemin, the active ingredient of the FDA-approved drug Panhematin, binds to BACH1 and favors its release from DNA for nuclear export and subsequent degradation. It has been shown that hemin increased mitochondrial gene expression and induced oxygen consumption rate in triple negative breast cancer cells (Fig. 3) [144]. Kelch-like ECH associated protein 1 (KEAP1) sequesters NFE2L2 in the cytoplasm. In the presence of dimethylfumarate (DMF), KEAP1 is modified allowing NFE2L2 translocation to the nucleus and the dissociation of BACH1. It has been shown in mouse embryonic fibroblasts that DMF induced mitochondrial biogenesis and increased the mtDNA copy number, the transcription levels of mtDNA-encoded genes and the amount of OXPHOS subunits [175]. Interestingly, several pharmacologic therapies, such as fluoxetine, curcumin and apigenin have been already prenatally tested in mouse models of DS and shown to have beneficial effects on neurogenesis and behavioral performance [[176], [177], [178]]. These three drugs have been shown to improve OXPHOS function and mitochondrial biogenesis [[179], [180], [181], [182], [183], [184], [185]]. Although none of them has been related to the chromosome 21 genes that repress mitochondrial biogenesis, all of them increase the expression of NFE2L2 [[186], [187], [188], [189], [190], [191]].

Resveratrol and pioglitazone are inducers of mitochondrial biogenesis (Fig. 3) [158,192,193]. Pioglitazone stimulated OXPHOS function in fibroblasts of DS individuals [194], and improved neurogenesis of human neuroblastoma SH-SY5Y cells [195]. Resveratrol reversed the mitochondrial energetic deficit and rescued the altered neurogenesis of NPCs from a mouse model of DS [30].

Finally, the DNP activates mitochondrial biogenesis in mice and rats [196,197], and in human rhabdomyosarcoma cells (Fig. 3) [156]. DNP is a mild OXPHOS uncoupler that increased the synthesis of pyrimidine nucleotide-derived compounds to produce phospholipids, neuritogenesis and neuronal differentiation [[198], [199], [200]]. Interestingly, it was shown that the total phospholipid content was significantly reduced in central cortex and cerebellum of DS individuals [201]. It has been also reported that cerebral cortex cells (CTb) derived from mouse fetuses with trisomy 16, an animal model of DS, overexpressed App, because this protein is coded in the mouse chromosome 16 (Mmu16). DNP decreased intracellular accumulation of App in these cells [202].

In mouse hippocampus, the ketogenic diet upregulated the Ppargc1a mRNA and protein levels and other markers of mitochondrial biogenesis [203]. In cells from other species, including human fibroblasts, β-hydroxybutyrate increased the PPARGC1A levels and oxygen consumption [203]. In pigs, maternal ketosis increased fetal brain weight [204]. The ketogenic diet during the prenatal and early postnatal periods had beneficial effects on the brain development of pyruvate dehydrogenase complex-deficient mammalian progeny [205]. The ketogenic diet has been proposed as a potential therapeutic option for DS individuals [206].

Pyrimidine nucleotides are needed for RNA synthesis and, after reduction to deoxyribonucleotides, for DNA synthesis. In addition, these nucleotides are fundamental for the activation of the sugars that will give rise to the glycoproteins and glycolipids of the plasma membrane and also for the activation of compounds that will produce phospholipids and related molecules for the production of membrane lipids [21,207]. Uridine nucleotides are also involved in the N-acetylglucosamination of many proteins. If this process in disrupted, intellectual disability may ensue [208]. Pyrimidine nucleotides are essential in proliferating cells. On the other hand, neurons are non-proliferating differentiated cells. Its differentiation process includes the formation of axons and dendrites and the maintenance of its huge surface that requires a continuous membrane synthesis, even in already differentiated neurons [209]. Dihydroorotate dehydrogenase (DHODH) links the de novo pyrimidine biosynthesis pathway and OXPHOS function. Ubiquinone is the electrons’ acceptor in the oxidation of dihydroorotate to orotate by the DHODH [21,207]. A Q deficiency, as previously reported in DS, impairs the de novo synthesis of pyrimidine nucleotides [210]. DSAD individuals show a reduction in plasma uridine concentrations [211]. Hence, a deficit of the OXPHOS system hampering Q reoxidation might cause a reduction in the de novo pyrimidine biosynthesis [212], in the proliferation of neuronal precursor cells and in their differentiation into neurons. We observed that uridine was able to prevent the negative effects of OXPHOS dysfunction on neuronal differentiation. Uridine prevented the decline of neuronal differentiation in cells overexpressing a mutant MRPS12 gene, in linezolid-treated cells, in linezolid-treated cells overexpressing a mutant MRPS12 gene, or in cyanide-treated cells [20,21].

The choline prenatal administration has shown to have beneficial effects on neurogenesis and behavioral performance when tested in a mouse model of DS [213]. Along with cytidine triphosphate (CTP), derived from uridine triphosphate (UTP), choline is required for phospholipid synthesis and brain development [21,214]. Therefore, choline or uridine administration could increase this process [215].

Although DS is a multigenic disorder and many cell pathways are affected, the early prenatal OXPHOS dysfunction is a key pathologic mechanism in the intellectual disability. Moreover, OXPHOS is a ubiquitous cell function and its deficiency might affect every organ of the body and hence, be related to many of the medical conditions associated to DS. Therefore, any strategy developed to improve OXPHOS function could become a successful therapeutic approach in DS.

The invitation to pregnant women to participate in trials for fetal DS therapy should be based on adequate preclinical evidence. There should be convincing experimental evidence based on cell and animal studies that ensures the safety and efficacy of the therapy [4]. These models, with their related problems, are considered suitable approaches for the study of human pathophysiology and response to drugs in DS [23,24,32]. To test this hypothesis, the overexpression of each one of these genes that repress mitochondrial biogenesis in cells capable of differentiate into neurons would help to study their effect on OXPHOS function and on neurogenesis. On the other hand, iPSCs from DS individuals would allow to analyze the combined effect of all these genes on OXPHOS function and neuronal differentiation. The effect of the proposed drugs on these cellular parameters would also be studied in both cell models. If promising results are obtained, mouse models with DS would allow to study the prenatal effect of the proposed drugs. In fact, some results obtained with prenatal therapy in animal models encourage to dedicate more time, effort and resources in this field [216]. Finally, some of the proposed drugs have been demonstrated to be safe, have been approved and are normally administered in pregnant women for the treatment of other pathologies.

This work was supported by grants from

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

61

62

63

64

65

66

67

68

69

70

71

72

73

74

75

76

77

78

79

80

81

82

83

84

85

86

87

88

89

90

91

92

93

94

95

96

97

98

99

100

101

102

103

104

105

106

107

108

109

110

111

112

113

114

115

116

117

118

119

120

121

122

123

124

125

126

127

128

129

130

131

132

133

134

135

136

137

138

139

140

141

142

143

144

145

146

147

148

149

150

151

152

153

154

155

156

157

158

159

160

161

162

163

164

165

166

167

168

169

170

171

172

173

174

175

176

177

178

179

180

181

182

183

184

185

186

187

188

189

190

191

192

193

194

195

196

197

198

199

200

201

202

203

204

205

206

207

208

209

210

211

212

213

214

215

216

We would like to thank Santiago Morales for his assistance with figures.