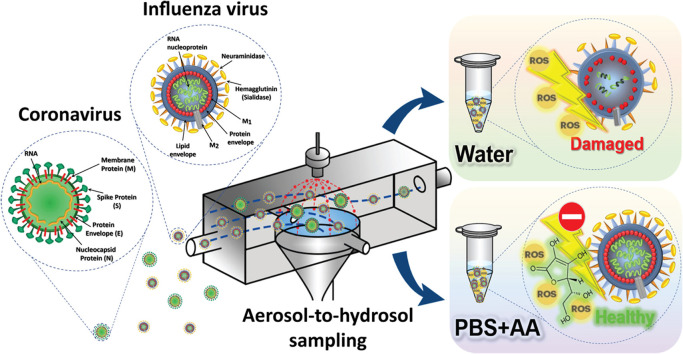

Airborne virus susceptibility is an underlying cause of severe respiratory diseases, raising pandemic alerts worldwide. Following the first reports of the novel severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2 in 2019 and its rapid spread worldwide and the outbreak of a new highly variable strain of influenza A virus (H1N1) in 2009, developing quick, accurate monitoring and diagnostic approaches for emerging infections is considered critical. Efficient air sampling of coronaviruses and the H1N1 virus allows swift, real-time identification, triggering early adjuvant interventions. Electrostatic precipitation is an efficient method for sampling bio-aerosols as hydrosols; however, sampling conditions critically impact this method. Corona discharge ionizes surrounding air, generating reactive oxygen species (ROS), which may impair virus structural components, leading to RNA and/or protein damage and preventing virus detection. Herein, ascorbic acid (AA) dissolved in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) was used as the sampling solution of an electrostatic sampler to counteract virus particle impairment, increasing virus survivability throughout sampling. The findings of this study indicate that the use of PBS+AA is effective in reducing the ROS damage of viral RNA by 95%, viral protein by 45% and virus yield by 60%.

Viral pandemics can cause major concern worldwide, being some of the greatest global health challenges experienced by humanity. In the last 110 years, five pandemics have emerged, all originating from different subtypes of the influenza A virus (Saunders-Hastings and Krewski, 2016), such as “Spanish flu, 1918”, “Asian flu, 1957”, and “Hong Kong flu, 1968”. More recently, “Swine flu, 2009”, where society faced a new, highly variable strain of the influenza A virus (H1N1), resulted in a global threat, and even today, the “COVID-19, 2019” pandemic caused by the novel coronavirus, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2), has presented itself as another great uncertainty of this century.

The influenza virus is an enveloped virus with a diameter of approximately 100 nm. The envelope of influenza A consists of a lipid bilayer and contains two major surface proteins, hemagglutinin (HA) and neuraminidase (NA), as well as glycoproteins (Skehel and Wiley, 2000). The influenza virus is a highly contagious and rapidly spreading respiratory virus (Ladhani et al., 2017). Several influenza transmission events are suspected to occur via viruses in the air (Richard and Fouchier, 2015). Similarly, coronaviruses (CoVs) are a large family of enveloped zoonotic RNA viruses. Their genome is a positive single-stranded RNA capable of causing respiratory, digestive, hepatic, and neurological disorders in a wide range of animal species (Marra et al., 2003). CoVs can also be transmitted from animals to humans, followed by subsequent person-to-person transmission (Zumla et al., 2016). The subfamily Coronavirinae contains four genera: alpha-, beta-, gamma-, and deltacoronaviruses (Van Der Hoek et al., 2004). An example of an alphacoronavirus is human coronavirus 229E (HCoV-229E), which was identified in the 1960s and results in a mild respiratory tract illness (Marra et al., 2003).

In contrast, betacoronaviruses mainly infect mammalian species and have attracted great interest in recent years as they are the leading cause of Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS-CoV) and severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS-CoV) (Van Der Hoek et al., 2004, Meo et al., 2020). In 2019, an atypical pneumonia outbreak, caused by a novel betacoronavirus, later known as SARS-CoV-2 was detected in China. The diameter of this virus varies from 60 to 140 nm (Liu et al., 2020, Zhu et al., 2020). SARS-CoV-2 contains major proteins such as spike proteins, nucleocapsid proteins, membrane proteins, and envelope proteins, which are needed to produce a structurally complete virus particle (Cohen and Normile, 2020, Dömling and Gao, 2020). SARS-CoV-2 has diverse biological and epidemiological characteristics, making it more contagious than MERS-CoV and SARS-CoV (Khan et al., 2020, Meo et al., 2020). Furthermore, the spread of the H1N1 influenza virus and SARS-CoV-2 occurs primarily through respiratory droplets that arise from individuals harboring the virus. Recently it is reported that small particles, droplet nuclei, and aerosol mode should not be ignored, especially in enclosed and indoor space (CDC, 2020). Hence, it is essential to monitor and detect airborne viruses. As in airborne bacterial monitoring, the first step is the air sampling of virus particles (Ladhani et al., 2017).

After the virus is successfully sampled, a wide array of emerging molecular technologies and biosensors can be used for detection (Hideshima et al., 2013, Nidzworski et al., 2014, Dalal et al., 2020). Immunofluorescence staining and flow cytometry have been frequently used as they allow the enrichment, quantification, and identification of certain pathogens (Schloter et al., 1995). For virus specific detection, quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR) can be used (Van Elden et al., 2001). Correspondingly, protein-based detection is also viable. For instance, enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) is a plate-based assay technique designed for detecting and quantifying substances such as proteins, antibodies, and hormones (Crowther, 2009).

Air sampling is the most critical part of any bio-aerosol study. Currently, there are various sampling methods available. Among these, electrostatic precipitation (EP) is an effective method, attributable to causing less damage and having higher relative recovery of sensitive bio-particles as well as its lower pressure drop (Mainelis, 1999, Mainelis et al., 2006). Moreover, a wide range of airborne bio-aerosols of different sizes can be collected using corona discharge (Hong et al., 2016). Furthermore, since most bio-detection methods need the bio-particles to be in a liquid suspended state, the use of electrostatics for aerosol-to-hydrosol (ATH) sampling is increasing (Yao et al., 2009, Han et al., 2010, Park et al., 2016, Piri et al., 2020).

However, recent findings have shown that applying EP may have inhibitory effects on airborne particles because EP results in the generation of oxygen/nitrogen-derived reactants (Mainelis, 1999, Yao et al., 2009). In particular, corona discharge can ionize the air, and result in reactive nitrogen species (RNS) and reactive oxygen species (ROS) production, which can be dissolved in the liquid underneath the discharge (Shimizu et al., 2011, Lukes et al., 2014, Winter et al., 2014, Kurake et al., 2017). It has been reported that the main species likely responsible for virus inactivation include superoxide anion (O2 -•), singlet oxygen (1O2), hydroperoxyl radical (HO2•), hydroxyl radical (OH•), hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), ozone (O3), nitric oxide (•NO), peroxynitrous acid (O=NOOH), nitrite (NO2 −), nitrate (NO3 −), nitrous acid (HNO2), and nitric acid (HNO3) (Aboubakr et al., 2015, Wende et al., 2015). Consistently, ROS such as 1O2 and OH• have a stronger destructive effect on microorganisms than other ROS (Laroussi and Leipold, 2004, Pavlovich et al., 2013, Lukes et al., 2014, Sekimoto et al., 2015).

During the ATH sampling process, the sampled virus particles are exposed to corona discharge, which can lead to protein oxidation and deformation (Boys et al., 2009). If either the RNA or protein is damaged throughout the collection process, the PCR or protein-based detections cannot occur. Therefore, it is crucial to avert damage during the sampling process. Similarly, the polarity and intensity of the applied current, voltage, type of liquid and the liquid flow rate (LFR) applied can have a significant impact on both the collection efficiency and survival state of the sampled viruses. To minimize the damage caused by these ROS, a phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and ascorbic acid (AA) solution (PBS+AA) can be used as an effective strategy to prevent the ROS damage. PBS+AA protects the bacteria from OH•, O2 -•, and 1O2 and prevents the formation of harmful compounds such as H2O2 and O=NOOH, resulting in improved bacterial viability (Ke et al., 2017). Moreover, AA is an ROS-scavenger that reacts with singlet oxygen, superoxides, and OH radicals (Surai, 2002). PBS+AA can terminate ROS-induced chain radical reactions through electron transfer owing to the resonance stabilized structure of AA, and therefore, can deactivate the free radicals produced during corona discharge exposure. After the electron transfer with AA, the resulted semidehydroascorbate is oxidized to dehydroascorbic acid, which is relatively unreactive and does not interfere with the cellular mechanisms (Saini et al., 2016, Alsayed et al., 2018).

Since virus particles are smaller and more sensitive than bacteria and have different physical and structural characteristics, it is necessary to investigate the degree of damage caused to virus particles and whether PBS+AA can exert any protective effects during ATH EP sampling of virus particles. Therefore, in this study, we investigated the application of PBS+AA as the sampling solution in our ATH EP air sampler; and evaluated the protective effect of PBS+AA when sampling airborne viruses such as H1N1 influenza virus and CoVs.

All experiments presented in this study were performed at a biosafety level 2 approved research facility. Coronavirus (HCoV-229E) stocks, with an initial virus concentration of 8.0 106 plaque-forming units (pfu) per milliliter (pfu/mL), were obtained from the Korea Bank for Pathogenic Viruses (Seoul, Korea). To prepare H1N1 influenza virus stocks, Madin-Darby canine kidney (MDCK) cells were obtained from the Korea Cell Line Bank (Seoul, Korea) then used as virus hosts, following the method of (Lin et al., 2017). MDCK cells were maintained in 75- and 175-cm2 cell-culture flasks (SPL Life Sciences, Korea) in which minimum essential medium (MEM) with Earle’s Balanced Salts Solution (MEM/EBSS; Hyclone, USA) was contained. For MDCK cell culture, all MEM/EBSS medium contained 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Gibco, USA) and 1% antibiotic-antimycotic solution (Gibco, USA). The cells were cultivated at 37 °C in 5% CO2 and 95% relative humidity atmosphere until they reached 90% confluence (every 3–4 days). The culture media of the MDCK cell-culture flasks were disposed, and the MDCK cells were rinsed with 1x PBS buffer (Biosesang, Korea). Then, the cells in the 75- and 175-cm2 cell-culture flasks were infected, respectively, using 3 and 6 mL FBS-antibiotic-antimycotic-free MEM/EBSS containing the H1N1 influenza virus (A/California/4/2009), initially obtained from BioNano Health-Guard Research Center (Daejeon, Korea), at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 0.01. The flasks were incubated for 45 min at 37 °C on a rocking shaker to allow virus internalization. After infection, the flasks were washed with 1x PBS buffer. Next, MEM/EBSS solution containing 0.25% trypsin (Hyclone, USA) was inserted to the flask. The flasks were placed at 37 °C for 48 h in 5% CO2 and 95% relative humidity condition. After 2 days, the culture media containing the newly produced H1N1 viruses were collected and centrifuged at 1200 rpm at 4 °C (for 10 min). The clarified supernatant was placed at − 80 °C for further analysis. A final H1N1 virus concentration of 1.5

Frozen H1N1 virus and HCoV-229E stocks were thawed until they reached 25 °C. One hundred microliters of each virus stock was separately added into 50 mL of sterile deionized (DI) water (pH = 7.0) or 50 mL of 1x PBS buffer containing 10 mM AA (Sigma-Aldrich, USA). The PBS+AA solution pH was adjusted to 7. The 10 mM AA concentration in PBS was selected since this concentration provided lowest ROS formation in liquid and caused highest protective effect to virus samples against corona discharge exposure (Figs. S2 and S3 of Supplemental materials). Then, using a peristaltic pump (Ismatec, Germany) 300 μL of each virus suspension (virus stock + DI water or virus stock + PBS+AA solution) was inserted into the air sampler, collected in a test tube with a LFR from 20 to 200 μL/min, and exposed to corona discharge. The air sampler was developed by Park et al. (2016) and details are described in Supplementary materials. Different LFR were used to have different exposure time to corona discharge. A constant negatively charged current of 13 µA was applied. After exposure, virus hydrosols were used for PCR, ELISA, and plaque assay analyses. A graphical representation of the experiment with the prepared virus hydrosols is shown in Fig. 1.

Test schematic with the prepared virus hydrosols.

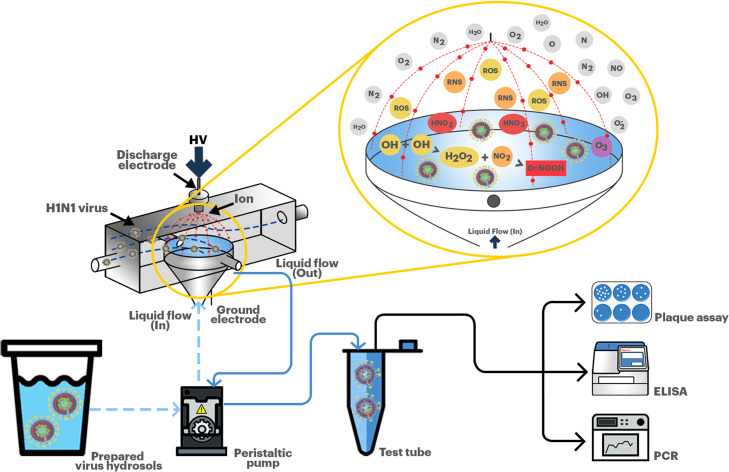

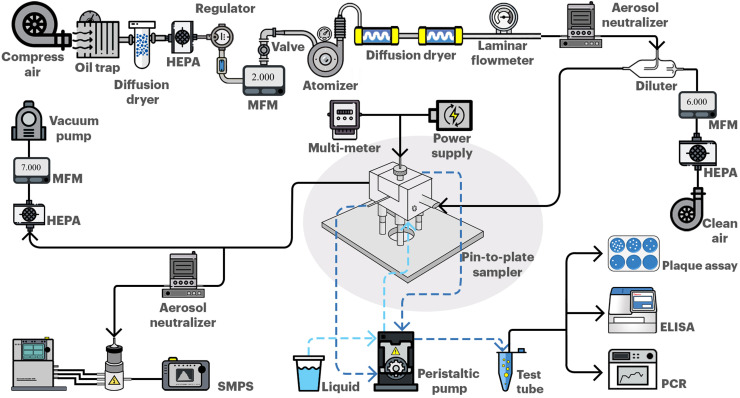

For the aerosolization and air sampling experiments, 8 mL of frozen H1N1 influenza virus stocks or HCoV-229E stocks were thawed to 25 °C and then added to 42 mL DI water. Next, utilizing a Collison atomizer (AG-01, HCT, Korea) the virus suspension (virus stock + DI water) was aerosolized. Compressed air entered the atomizer at 3 L/min flow rate. The pressure drop from the air jet directed the aerosolization of the virus particles. After exiting the atomizer, the virus particles passed through two diffusion dryers and an aerosol charge neutralizer (Soft X-ray charger 4530, HCT, Korea) to remove moisture and particle charges, respectively. Then, the air containing the virus particles was diluted with clean air at a flow rate of 5 L/min in a dilutor before entering the sampler; thus, the total air flow rate of the sampler was 8 L/min. Subsequently, a constant negatively charged current of 13 µA was applied and the aerosolized virus particles were sampled on a continuously flowing liquid solution (DI or PBS+AA) at an LFR of 50 μL/min. This LFR was selected for test with virus aerosols since up to this LFR the intensity of corona discharge damage was reasonable and since the lower the LFR indicates a more concentrate virus sample. The current-voltage correlation was assessed using a multimeter (Gossen Metrawatt, Germany). After air sampling, 300 μL of the sampled virus particles was aliquoted for PCR, ELISA, and plaque assay analyses. A graphical representation of the experiments with the aerosolized viruses is shown in Fig. 2.

Schematic representation of the test with H1N1 influenza virus and HCoV-229E aerosols.

PCR amplification cycles are linked to the initial number of template RNAs. Delayed amplification with a high PCR cycle number (Ct) is correlated with a low virus content or virus impairment due to corona discharge exposure. The damaging effect of corona discharge on HIN1 influenza viral RNA was assessed using a PowerChek™ Pandemic H1N1 Real-time PCR Kit (KogeneBiotech, Korea), whereas the effect on HCoV-229E RNA was assessed using a Coronavirus 229E/OC43/NL63/HKU1 Real-time PCR Kit (64000F, Kogenebiotech, Korea). For this assay, 300 μL of each sample was used. Real-time PCR was performed in a total volume of 20 μL (15 μL PCR reaction mixture and 5 μL template RNA) using a Thermo Scientific™ PikoReal™ Real-Time PCR System (TCR0096, USA). Thermal cycling conditions were as follows: 30 min at 50 °C; 10 min at 95 °C; 35 cycles of 15 s at 95 °C for the H1N1 influenza virus while 45 cycles of 15 s at 95 °C for HCoV-229E, and 1 min at 60 °C. Procedures were performed according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

In this study, ELISA analysis was performed only for H1N1 influenza virus. HA is the outermost and most antigenic surface protein of the influenza virus (Petrova and Russell, 2018). In principle, detection is made by estimating the conjugated enzyme activity via incubation with a substrate (Lequin, 2005). H1N1-HA antibody quantification using solid-phase sandwich ELISA was used to measure the HA content. The H1N1 influenza virus HA protein concentration was assessed using a commercially available ELISA assay, following the manufacturer’s guidelines (Sino Biological Inc., Germany). A 96-well assay plate was pre-coated with a mouse antibody against H1N1 influenza virus HA protein (H1N1-HA antibody). Briefly, all reagents were thawed to 25 °C, 300 μL of washing buffer was added to each well and the plate was washed three times, any remaining washing buffer was removed by blotting the plate with absorbent towels. Then, 100 μL of serially diluted protein standard or test virus suspension (DI or PBS+AA) was added into each well. The test-plate was sealed and incubated at 25 °C for 2 h. Then, the wells were washed three times with washing buffer, and the remaining washing buffer was cleared by blotting the test-plate with absorbent towels. Next, 100 μL of the detection solution was added to each well, the test-plate was incubated at 25 °C for 1 h. The solution was removed, and the test-plate was washed three times with washing buffer. Then, 200 μL of substrate solution was added into each well, and the test-plate was incubated at 25 °C for 20 min while protecting it from light exposure. Immediately after incubation, 50 μL of stop solution was added to each well, and the optical density was determined within 30 min using a microplate reader set to 450 nm.

For experiments with the H1N1 influenza virus, on day one, 5.0 × 105 MDCK cells suspended in 1 mL of MEM/EBSS culture media were seeded on 6-well plates (SPL Life Sciences, Korea). The plates were incubated overnight at 37 °C in an atmosphere of 5% CO2 and 95% relative humidity. On day 2, confluent monolayers of MDCK cells were washed twice with 1x PBS buffer and then infected with 800 μL of serial 10-fold dilutions of the H1N1 influenza virus samples in FBS-antibiotic-antimycotic-free MEM/EBSS. Virus infection was induced by incubation at 37 °C for 1 h with frequent agitation. After infection, the virus inoculums were aspirated, and the monolayers were washed once with 1x PBS buffer. Then, the monolayers were overlaid with 3 mL of agar overlay medium, which consisted of 2x Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s Medium (DMEM; Gibco, USA), 7.4 g/L sodium bicarbonate (Sigma-Aldrich, USA), 1% antibiotic-antimycotic solution (Gibco, USA), 2.5% HEPES 1 M (Gibco, USA), 5.3% bovine serum albumin (BSA) 7.5% fraction V (Sigma-Aldrich, USA), 2 µg/mL tosyl phenylalanyl chloromethyl ketone (TPCK)-treated trypsin (Sigma-Aldrich, USA), and 2% agar (Lonza SeaPlaque agarose, USA). The plates were incubated at 25 °C for 10–15 min until the agar solidified and incubated at 37 °C in an atmosphere of 5% CO2 and 95% relative humidity for 3–5 days (until plaques were observed).

For experiments with HCoV-229E, Medical Research Council-5 (MRC-5; human lung fibroblast) cells were obtained from the Korea Cell Line Bank (Seoul, Korea). The MRC-5 cells were maintained in 75- and 175-cm2 cell-culture flasks containing MEM/EBSS supplemented with 10% FBS, 2.5% HEPES 1 M, and 1% antibiotic-antimycotic solution. The cells were cultivated at 37 °C in 5% CO2 and 95% relative humidity atmosphere until they reached 90% confluence. On day 1, 1.0 × 106 cells suspended in 1 mL of MEM/EBSS culture media were seeded on 6-well plates. The plates were incubated overnight at 37 °C in an atmosphere of 5% CO2 and 95% relative humidity. On day 2, confluent monolayers of MRC-5 cells were washed twice with 1x PBS buffer and then infected with 800 μL of serial 10-fold dilutions of the HCoV-229E samples in FBS-antibiotic-antimycotic-free MEM/EBSS. Virus infection was induced by incubation at 37 °C for 1 h with frequent agitation. After infection, the virus inoculums were aspirated, and the monolayers were washed once with 1x PBS buffer. Then, the monolayers were overlaid with 3 mL of agar overlay medium, which consisted of 2x DMEM, 7.4 g/L sodium bicarbonate, 1% antibiotic-antimycotic solution, 2.5% HEPES 1 M, and 1% agar. The plates were incubated at 25 °C for 10–15 min until the agar was solidified and incubated at 37 °C in an atmosphere of 5% CO2 and 95% relative humidity for 1–2 weeks (until plaques were observed). Agar-covered monolayers were then fixed in 10% formalin (Daejung, Korea). The agar was removed using a spatula, and the fixed cells were stained using 0.5% crystal violet solution (Sigma-Aldrich, USA), then, the plaques were counted under transmitted light. After counting the plaques, the concentration of the virus suspension in pfu/mL was calculated using the following equation (Eq. 1):

The sampling process continued for 20 min. Throughout the sampling, the number concentration of H1N1 influenza virus and HCoV-229E aerosols were assessed using a scanning mobility particle sizer (SMPS; TSI model 3936L76, USA) which measures the electrical mobility diameter of particles between 14 and 600 nm. The SMPS consists of a condensation particle counter (CPC; TSI model 3776, USA), a classifier controller (3080, TSI, USA), a differential mobility analyzer (DMA; TSI model 3081, USA), and an aerosol charge neutralizer (4530, HCT, Korea).

The sampler’s collection efficiency (η) was determined based on the following equation (Eq. 2), in which

The total concentration of virus particles sampled inside the liquid (N

l) was calculated based on the following equation (Eq. 3), where N is the virus particle concentration in the air (N =

All experiments were performed in triplicate, as specified in the figure legends. Data are expressed as the mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM). The statistical significance of normally distributed data was determined using an unpaired t-test or one-way analysis of variance. Multiple comparisons were made, and the p value was corrected using Tukey’s correction. Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism 8 (GraphPad Software, USA). Significant differences are represented by *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, and ***p < 0.001.

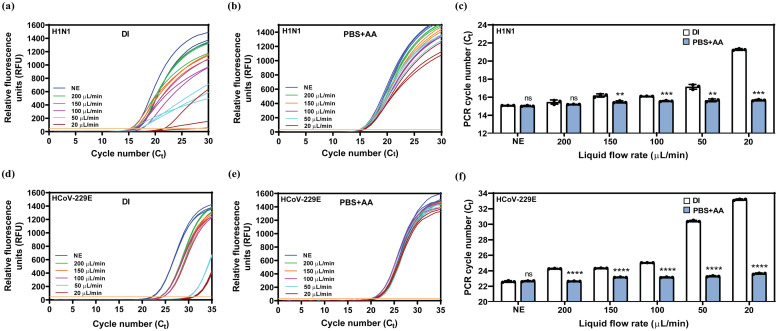

Fig. 3 shows the PCR result analysis for the prepared DI and PBS+AA virus suspensions (10 mM AA concentration). Amplification curves were obtained for the H1N1 influenza virus in the multiplex PCR reaction for the DI (Fig. 3a) and PBS+AA suspensions (Fig. 3b), respectively. Similarly, amplification curves for HCoV-229E in the multiplex PCR reaction for the DI (Fig. 3d) and PBS+AA suspensions (Fig. 3e) are shown. Ct values (X-axis) are displayed in relation to the fluorescence obtained (Y-axis). Consistently, the DI solutions showed persistent viral damage with a decrease in the liquid flow rate, which is directly proportional to an increased Ct for the H1N1 influenza virus and for HCoV-229E. In the case of H1N1 virus, the Ct value for the non-exposed (NE) DI and PBS+AA samples was 15 (Fig. 3c). However, as the LFR decreased, due to RNA damage, the Ct value increased. In the DI samples, this increased 0.7-fold, whereas for the PBS+AA sample, it increased only 0.05-fold when the LFR was 20 μL/min. In contrast, for HCoV-229E, the PBS+AA protective effect was more noticeable. The PCR cycle number for the NE DI and PBS+AA samples was 23; similar to the case of the H1N1 virus, as the LFR decreased, the PCR cycle number increased. In the DI samples, the PCR cycle number increased 0.6-fold, whereas it increased only 0.04-fold in the PBS+AA samples when the LFR was 20 μL/min (Fig. 3f). Collectively, the results indicate that PBS+AA displays a robust and consistent sigmoidal function with a higher endpoint relative fluorescence unit (RFU) value, representing a more efficient PCR and hence showing lower virus impairment than DI. Hence, PBS+AA displayed a significantly lower Ct value compared to DI, indicating that PBS+AA prevents viral RNA from being damaged.

qRT-PCR amplification curves with the prepared H1N1 influenza virus and HCoV-229E hydrosols after corona discharge exposure. (a) Test with the prepared H1N1 virus (DI). (b) Test with the prepared H1N1 virus (PBS+AA). (c) The effect of liquid flow rate (exposure time) on the H1N1 virus suspensions. (d) Test with the prepared HCoV-229E (DI). (e) Test with the prepared HCoV-229E (PBS+AA). (f) The effect of liquid flow rate (exposure time) on the HCoV-229E suspensions. The results represent the mean ± SEM of three independent assays. Significant differences are represented by *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, and ***p < 0.001. DI, deionized water; PBS+AA, phosphate-buffered saline and ascorbic acid solution; NE, non-exposed; RFU, relative fluorescence units.

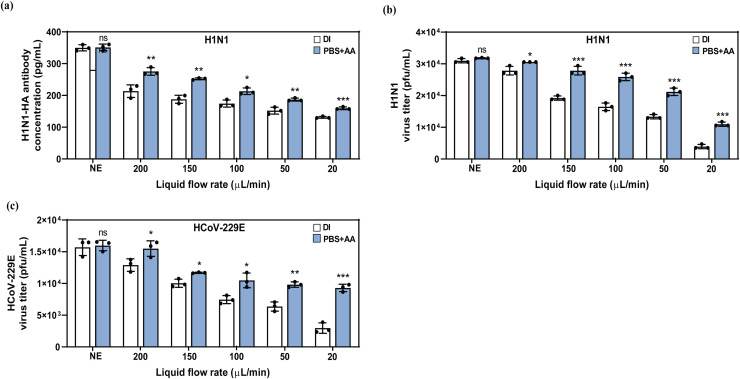

The H1N1-HA antibody concentration in DI diminished progressively in a liquid flow rate-dependent manner ( Fig. 4a). When the LFR was 20 μL/min, the DI sample showed a significant reduction (0.6-fold) (Fig. 4a). Notably, after corona exposure, the H1N1-HA antibody content in PBS+AA was greater than that in DI, despite the decrease in the LFR. Hence, the results indicate the potential use of PBS+AA as a protective agent when sampling the H1N1 influenza virus or similar viruses.

Comparison of H1N1-HA content and H1N1 influenza virus & HCoV-229E infectivity between the DI and PBS+AA hydrosols after corona discharge exposure. (a) H1N1-HA antibody quantification. (b) H1N1 influenza virus plaque titrations assay. (c) HCoV-229E plaque titrations assay. The results represent the mean ± SEM of three independent assays. Significant differences are represented by *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, and *** p < 0.001. DI, deionized water; PBS+AA, phosphate-buffered saline and ascorbic acid solution; NE, non-exposed.

To further evaluate H1N1 influenza virus and HCoV-229E infectivity upon corona discharge exposure, plaque assays were performed. In principle, the plaque forming ability of a single infectious virus on a cell-culture monolayer can be measured by this assay. When replication takes place, the host cell dies. Virus titers were determined by counting the number of pfu. The results are shown in Fig. 4b (H1N1 influenza virus) and Fig. 4c (HCoV-229E). Compared to the DI samples, PBS+AA was able to preserve the virus yield, showing a higher number of plaques. In case of H1N1 influenza virus, compared to the NE samples, PBS+AA was showed a 0.6-fold decrease, whereas the DI sample showed a 0.9-fold reduction at 20 μL/min. Similarly, HCoV-229E plaque titrations assay showed a 0.4-fold decrease in the PBS+AA sample, whereas the DI sample showed a 0.8-fold reduction at 20 μL/min. The protective effect of PBS+AA on H1N1 virus plaque formation is tightly correlated with the LFR (corona discharge exposure time).

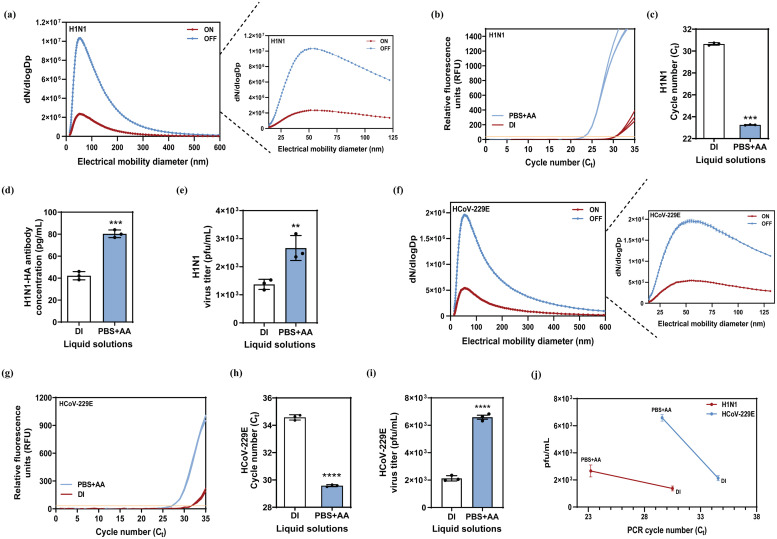

Fig. 5a shows the size distributions of aerosolized H1N1 influenza virus when the sampler was on and off. The collection efficiency of the sampler was 75% (Eq. 2). The PCR analysis revealed a substantial decrease in cycle number when PBS+AA was used as the sampling liquid. The Ct value for the DI sample was 31, whereas the Ct value was 23 for the PBS+AA sample; this 0.8-fold increase of Ct value in the DI sample was correlated with the viral RNA impairment induced upon corona exposure (Fig. 5b and c). Moreover, the ELISA results for the PBS+AA sample showed a 1.1-fold increase in the H1N1-HA antibody concentration than for the DI sample (Fig. 5d). Similarly, virus titers were determined by counting the number of plaques. Compared to the DI solution, the PBS+AA solution was able to preserve virus yields to a greater extent (1.3-fold) (Fig. 5e). The size distributions of aerosolized HCoV-229E, when the sampler was on and off, are shown in Fig. 5f. In line with results of test with H1N1 influenza virus, HCoV-229E experiments also revealed a lower Ct value (Ct = 29) for the PBS+AA sample than for the DI sample (Ct = 34). This increase of Ct value in the DI sample was correlated with the viral RNA impairment, induced upon corona discharge exposure (Fig. 5g and h). The virus titers determined that PBS+AA solution was able to preserve virus yields to a greater extent (2.1-fold) (Fig. 5i), when compared to DI samples. The correlation between PCR and virus viability results are shown in Fig. 5j. Collectively, these results imply that PBS+AA preserves virus plaque formation by exerting protective effects during corona exposure.

Evaluation of the protective effect of PBS+AA using tests with H1N1 influenza virus and HCoV-229E aerosols. In HIN1 influenza virus: (a) The size distribution of the aerosolized virus. (b) qRT-PCR amplification curves for the DI and PBS+AA samples. (c) The effect of liquid type on the PCR Ct values in DI and PBS+AA. (d) H1N1-HA antibody quantification. (e) Plaque titrations assay. In HCoV-229E: (f) The size distribution of the aerosolized virus. (g) qRT-PCR amplification curves for the DI and PBS+AA samples. (h) The effect of liquid type on the PCR Ct values in DI and PBS+AA. (i) Plaque titrations assay. (j) The correlation between PCR and virus viability results. The results represent the mean ± SEM of three independent assays. Significant differences are represented by *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, and ***p < 0.001. DI, deionized water; PBS+AA, phosphate-buffered saline and ascorbic acid solution; NE, non-exposed; RFU, relative fluorescence units.

The development of standardized methods to minimize sampling damage is one of the significant scientific challenges in the field of bio-aerosols. Bio-aerosol sampling through EP may result in the collection of non-viable particles due to the electric charge applied to bio-particles (Mainelis, 2020). Several approaches for the sampling evaluation of bio-aerosols have been developed (Sirikanchana et al., 2008). To determine viral concentrations, virus cultivation is commonly used. However, most bio-aerosol sampling techniques affect virus infectivity, making virus cultivation inadequate for calculating the concentrations of airborne viruses (Verreault et al., 2008). Another approach is the employment of qRT-PCR to confirm the presence of amplifiable virus genomes, which can be correlated with undamaged virus samples. Thus, for effective amplification, the sample preparation and quality of collection for PCR should be improved.

The PCR results of the test with prepared virus hydrosols showed higher Ct values for the DI samples and significantly lower Ct values for the PBS+AA samples in both H1N1 influenza and HCoV-229E virus hydrosols. Since the DI and PBS+AA samples had the same initial virus concentration, the difference in Ct values represented a direct and valid indication of the protective effect of PBS+AA against corona discharge exposure. In addition, compared to the H1N1 influenza virus, HCoV-229E showed greater impairment due to corona discharge exposure (Fig. 3f). This implies that CoVs are more sensitive to corona discharge exposure than influenza viruses. However, when PBS+AA was used, the protective effect was noteworthy enough to maintain similar Ct values in both virus samples for different LFR (different exposure times). Thus, it is suggested that PBS+AA is suitable for the electrostatic sampling of influenza and coronaviruses. Moreover, the results show a substantial difference in the Ct values and imply the key role of PBS+AA in preventing ROS damage during the sampling process. In particular, the protective effect of PBS+AA against corona discharge-generated ROS is much greater for sensitive virus particles such as HCoV-229E and SARS-CoV-2.

Similarly, ELISA was used to evaluate the effect of ROS damage on viral proteins. Proteins are less sensitive to heat and high salinity and therefore have higher stability than RNA and DNA (Forterre, 2005). However, oxidative damage due to corona discharge generates ROS, which can cause loss of protein functionality (Berlett and Stadtman, 1997, Stadtman and Levine, 2003). By performing ELISA, we consistently discerned between healthy and damaged H1N1 influenza HA proteins since the virus surface contains host binding antigens that are responsible for binding with host cells and aid the virus in infecting the host cell. If these surface proteins are damaged, the virus becomes inactivated and loses its capability of causing an infection. This may hold positive outcomes for the general population; however, for virus analysis, quantification, isolation, and vaccine-development, this represents a challenge since it is imperative that the sampled virus retains its infectivity and replication properties. Similarly, the ability of viruses to form plaques was investigated through plaque assay analysis by examining the infectability of the virus after corona discharge exposure and the sampling process. Generally, a low pfu/mL value is correlated to a high PCR cycle number while a high pfu/mL value is correlated to a low PCR cycle number (Zhang et al., 2013). The plaque assay results suggested that the pfu/mL values for the samples in PBS+AA were higher than those for the samples in DI. The results for plaque assay analysis are also in line with the obtained PCR results, indicating that PBS+AA is significantly effective in reducing the in preventing the loss of virus infection due to ROS damage during sampling process.

Taken together, the outbreak of the Swine flu pandemic in 2009 and the COVID-19 pandemic being faced at present have raised global concerns regarding the airborne transmission of infectious viruses. Developing quick and accurate monitoring and diagnostic approaches requires efficient collection methods. In this study, we investigated a new strategy to increase the survivability of airborne viruses such as the H1N1 influenza virus and coronaviruses such as HCoV-229E under ATH EP sampling. The protective effect of PBS+AA against ROS on viral RNA, protein, and host infectability was investigated. The results suggest that using PBS+AA as the sampling liquid in an ATH EP sampler can lead to profound protective effects against corona discharge and significantly improve virus integrity, leading to enhanced virus detection via a significant increase in the undamaged viral RNA and/or protein. PBS+AA can be applied to minimize the damage to bio-aerosols such as viruses and bacteria during electrostatic sampling. Compared to the NE samples, the use of PBS+AA reduced the corona discharge-generated ROS damage of viral RNA by 95% and preserved viral protein and virus yield by 45% and 60%, respectively. The results presented in this study provide sufficient evidence that PBS+AA plays a crucial role in protecting small and sensitive viruses such as influenza and coronaviruses and can significantly contribute to enhancing current bio-aerosol monitoring systems, resulting in the prevention of future virus pandemics such as the “COVID-19, 2019” pandemic.

Amin Piri: Conceptualization, Methodology, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Validation, Visualization, Resources, Writing - review & editing. Hyeong Rae Kim: Validation. Dae Hoon Park: Validation, Visualization. Jungho Hwang: Supervision, Project administration, Writing - review & editing.

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

This research was supported by the Technology Innovation Program Industrial Technology Alchemist Project (20012215, Intelligent platform for in-situ virus detection and analysis), funded by the Ministry of Trade, Industry and Energy (MOTIE), Korea. Additionally, Amin Piri would like to thank Dr. Adriana Rivera-Piza for her invaluable and insightful assistance.