Use of a silyl supported stannylene (MesTerSn(SitBu3) [MesTer=2,6‐(2,4,6‐Me3C6H2)2C6H3] enables activation of white phosphorus under mild conditions, which is reversible under UV light. The reaction of a silylene chloride with the activated P4 complex results in facile P‐atom transfer. The computational analysis rationalizes the electronic features and high reactivity of the heteroleptic silyl‐substituted stannylene in contrast to the previously reported bis(aryl)stannylene.

A heteroleptic silyl supported stannylene enables activation of white phosphorus and use as P‐atom transfer reagent.

Organophosphorus compounds offer unique structural and electronic properties and therefore have gained considerable attention in the past decades. [1] Their synthesis classically involves the energy intensive and hazardous chlorination of white phosphorus (P4).[ 1d , 1e ] As an alternative, the activation of P4 under mild conditions and subsequent transformation to organic molecules presents an attractive approach towards P4 utilization.[ 1a , 1b , 1c , 1e , 1f ] To date, a plethora of examples for transition metal mediated P4 activation has been achieved.[ 1b , 1e ] Very recently, in an elegant study Wolf and co‐workers demonstrated the photocatalytic transformation of P4 to aryl phosphines and phosphonium salts by use of an iridium catalyst. [2] In contrast to transition metals, activation of P4 with main group elements is limited to only a handful of examples,[ 1a , 1c , 1f , 3 ] and catalytic utilization of P4 with main group compounds remains so far elusive.

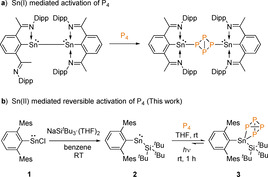

Recently, low valent heavier group 14 carbene homologues, namely tetrylenes ([R2E:] E=Si, Ge), which are in the +II oxidation state, have given new impetus to the field of P4 activation. [4] Examples of both silylenes[ 4a , 4c , 4d , 4f , 5 ] and germylenes have been reported to activate P4. [4b] Notably, a diaryl germylene [MesTer2Ge:], (MesTer=2,6‐(2,4,6‐Me3C6H2)2C6H3] provided the first main group mediated reversible activation of the P−P bond in P4. [4b] This is an important discovery, as reversibility is a key step towards main group mediated catalysis. [6] To the best of our knowledge, there is only one example of a dimeric, low‐valent SnI complex for the controlled activation of P4 (Scheme 1 a), whereas such reactivity is unknown for the heavier tetrylene analog, stannylene [R2Sn:]. [7]

Activation of P4 with low‐valent tin complexes (Dipp=2,6‐iPr2(C6H3), Mes=2,4,6‐Me3(C6H2).

Stannylenes present themselves as ideal candidates for bond activation and catalysis, due to the increased stability of the +II oxidation state compared to the lighter group 14 tetrylenes. [8] It has previously been shown that the SnII‐SnIV redox couple can be manipulated by use of strongly σ‐donating boryl ligands to enable dihydrogen activation. [8c] Therefore, we postulated that use of electropositive silyl groups, which have been widely employed as stabilizing ligands in low valent main group chemistry, [9] may enable the activation of strong bonds.

Our study began with the targeted isolation of the sterically demanding homoleptic bis(silyl)stannylene [(SitBu3)2Sn]. However, various attempts to isolate [(SitBu3)2Sn] was unsuccessful in our hands. Thus, our attention turned to the synthesis of a heteroleptic silyl substituted stannylene. The heteroleptic silyl stannylene 2 [MesTerSn(SitBu3)] was isolated via treatment of chlorostannylene 1 [MesTerSnCl) with one equivalent of NaSitBu3⋅(THF)2. Compound 2 was isolated in 80 % yield as a dark blue solid (Scheme 1 b) and is soluble in polar solvents such as tetrahydrofuran, but poorly soluble in nonpolar organic solvents such as benzene or toluene. The 119Sn{1H} NMR spectrum of compound 2 showed a characteristic signal for the tin center at δ 197 ppm, which is significantly upfield in comparison to 1 (562 ppm) and the bis(aryl)stannylene (MesTer)2Sn (1971 ppm).[ 8e , 10 ] This indicates an electron rich SnII center, which can be attributed to the substituent effect (SitBu3 vs. MesTer). In the 29Si NMR spectrum a distinct signal was observed at 94.7 ppm for the silicon atom of SitBu3. The calculation of NMR shifts for heavy elements represents a challenge due to spin‐orbit coupling effects and limitations of common basis sets/ effective core potentials (ECP). [11] Nevertheless, calculations at the PBE0‐D3/def2‐TZVPP//PBE0‐D3/def2‐SVP level of theory with the def2‐ECP reproduce the order of the 119Sn NMR shifts (1: −170 ppm; 2: −314 ppm; (MesTer)2Sn: 664 ppm) and hence corroborate a comparably electron rich SnII atom in 1.

Single crystal X‐ray diffraction (SC‐XRD) analysis confirmed the identity of compound 2, with the two‐coordinate Sn center bound by one SitBu3 and m‐terphenyl group (Figure 1). The ∡ C1‐Sn1‐Si1 bond angle in 2 is 113.50(14)° and falls within the range of aryl substituted two‐coordinate SnII complexes (96.9–117.6°). [12] Notably, two‐coordinate stannylenes [R2Sn] with broad bond angles (∡ R‐Sn‐R=112 to 118°) have been shown to activate a wide range of small molecules.[ 8c , 8d , 8e ]

![Molecular structure of compound 2 in the solid state. Ellipsoids are set at the 50 % probability level; hydrogen atoms are omitted for clarity. Selected bond lengths [Å] and bond angles [°]: Si1–Sn1 2.6981(17), Sn1–C1 2.217(5), C1‐Sn1‐Si1 113.50(14).](/dataresources/secured/content-1765942124495-abd67f2a-9996-4408-a737-e608ae0110c4/assets/ANIE-60-3519-g001.jpg)

Molecular structure of compound 2 in the solid state. Ellipsoids are set at the 50 % probability level; hydrogen atoms are omitted for clarity. Selected bond lengths [Å] and bond angles [°]: Si1–Sn1 2.6981(17), Sn1–C1 2.217(5), C1‐Sn1‐Si1 113.50(14).

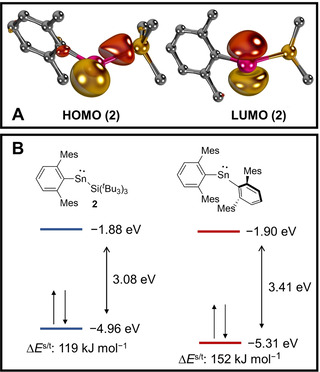

To understand the electronic structure of 2, we performed a computational analysis. The HOMO (highest occupied molecular orbital) and LUMO (lowest unoccupied molecular orbital) of 2 (Figure 2 A) are centered at the Sn moiety and represent the filled px‐ and empty pz‐orbitals of the tin center. The two frontier orbitals are separated by 3.08 eV (ΔE s/t=119 kJ mol−1; Figure 2 B, left), which is considerably smaller than for the reported diaryl stannylene (MesTer2Sn, 3.41 eV; ΔE s/t=152 kJ mol−1; Figure 2 B, right) and suggests higher reactivity for the former. Most salient, whilst the energy levels of the LUMOs are essentially equivalent (2, −1.88 eV; MesTer2Sn, −1.90 eV), the HOMO of 2, associated with the px orbital and showing overlap with the Si atom, is much higher in energy (2, −4.96 eV; MesTer2Sn, −5.31 eV). This corroborates that enhanced σ‐donation from the silyl substituent considerably enhances the nucleophilicity of 2 in relation to the bis(aryl)‐substituted congener, whereas the electrophilicity of both compounds should be similar.

Frontier orbitals of 2 (A), their energies and vertical singlet/triplet gap ΔE s/t (B, left) and comparison with MesTer2Sn (B, right) as obtained at the PBE0‐D3/def2‐TZVPP//PBE0‐D3/def2‐SVP level of theory.

Encouraged by the computational results, we hypothesized whether compound 2 may activate P4. A trial NMR scale reaction of 2 with P4 at room temperature afforded an immediate color change from blue to blue‐green and a yellow solution was obtained within 15 min. Multinuclear NMR analysis confirmed the quantitative conversion of 2 to a tin polyphosphide complex. The 31P{1H} NMR spectrum revealed resonances for three distinct 31P nuclei (X, A and B) at δ X=134.3, δ A=−211.9 and δ B=−278.2 ppm. Interestingly, the downfield resonance signal δ X is split into a doublet of doublets (1 J(PX,PA)=159.0, 1 J(PX,PB)=154.8 Hz) while each of the two up‐field signals show a doublet of triplets (1 J(PX,PA)=159.0, 1 J(PA,PB)=160.7 Hz), indicating an ABX2 type splitting pattern. This observation is in line with the isovalent [LSiP4, L=β‐diketiminate] complex reported by Driess and co‐workers. [4a] The 119Sn spectrum of 3 exhibits a triplet resonance at δ=26.3 ppm (1 J Sn‐P=323.8 Hz), which is upfield compared to 1 and falls in the range of known tin polyphosphide complexes (δ=+130.4 to −1540.0 ppm). [13] Notably, tin polyphosphide complexes are typically generated by salt metathesis reactions with the metal polyphosphide and stannylene.[ 13a , 13b , 13c , 14 ] Based on these observations, compound 3 is proposed to contain a coordinated P4 unit at the Sn center. Repetition of this reaction on a preparative scale enabled the isolation of compound 3 [MesTerSn(P4)SitBu3] as a yellow solid in 91 % yield. Thus, facile access to a tin polyphosphide, directly from P4, presents an attractive route in P4 utilization.

SC‐XRD of 3 confirmed the coordination of MesTerSn(SitBu3) across the P4 unit yielding a tetrahedral tin center with a tricyclic SnP4 core (Figure 2). Notably, regioselective activation of P4 at main group centers is rare.[ 1a , 1c ] Compound 3 is isostructural to the reported LSiP4 and (m‐Ter)2GeP4 complexes (Figure 3).[ 4a , 4b ] In 3, two Sn‐P bond lengths are almost identical (Sn1‐P1 2.5714(7) and Sn1‐P4 2.5767(7) Å) and fall within the range of Sn‐P single bonds.[ 13b , 13c , 14 ] The exterior P−P bond length of the tetrahedron is P3‐P2 2.1638(10) Å, which is slightly shorter than the P‐P bond length adjacent to the Sn center (P4‐P2 2.2282(9) to P4‐P3 2.2158(10) and P2‐P1 2.2341(10) Å). Interestingly, in compound 3 the C1‐Sn1‐Si1 bond angle (124.77(5)°) is wider than in 2 (113.50(14)°).

![Molecular structures of compound 3 in the solid state. Ellipsoids are set at the 50 % probability level; hydrogen atoms are omitted for clarity. Selected bond lengths [Å] and bond angles [°]: Si1–Sn1 2.6960(7), Sn1–C1 2.223(2), Sn1–P1 2.5714(7), Sn1–P4 2.5767(7), P2–P3 2.1638(10), P4–P3 2.2158(10), P4–P2 2.2282(9), P2–P1 2.2341(10), P3–P1 2.2260(10), C1‐Sn1‐Si1 124.77(5).](/dataresources/secured/content-1765942124495-abd67f2a-9996-4408-a737-e608ae0110c4/assets/ANIE-60-3519-g003.jpg)

Molecular structures of compound 3 in the solid state. Ellipsoids are set at the 50 % probability level; hydrogen atoms are omitted for clarity. Selected bond lengths [Å] and bond angles [°]: Si1–Sn1 2.6960(7), Sn1–C1 2.223(2), Sn1–P1 2.5714(7), Sn1–P4 2.5767(7), P2–P3 2.1638(10), P4–P3 2.2158(10), P4–P2 2.2282(9), P2–P1 2.2341(10), P3–P1 2.2260(10), C1‐Sn1‐Si1 124.77(5).

Further calculations at the DLPNO‐CCSD(T)/def2‐TZVPP//PBE0‐D3/def2‐SVP level of theory with consideration of solvation effects (SMD) shed further light on both the kinetics as well as thermodynamics of the conversion of 2 to 3 compared to the bis(aryl)stannylene system (Figure 4). The barrier for the former (ΔG=+86 kJ mol−1) was found to be 19 kJ mol−1 lower than for the latter (ΔG=+105 kJ mol−1). Accordingly, orbital overlap in the asymmetric (Sn‐P1: 2.91 Å; Sn‐P2: 2.78 Å) transition state further corroborates a dominating nucleophilic interaction in the overall ambiphilic activation step. This highlights the influence of the electropositive silyl group on the SnII center in enabling the activation of P4 in contrast to the bis(aryl) system and corroborates our overall design principle.

![Gibbs free energy profile for P4 activation by MesTerSn(SitBu3) 2 [blue —] and (MesTer)2Sn [red —] obtained at the DLPNO‐CCSD(T)/def2‐TZVPP//PBE0‐D3/def2‐SVP level of theory and bond lengths, given in Å, as well as HOMO of transition state. Mesityl and tBu substituents as well as hydrogen atoms are omitted for clarity.](/dataresources/secured/content-1765942124495-abd67f2a-9996-4408-a737-e608ae0110c4/assets/ANIE-60-3519-g004.jpg)

Gibbs free energy profile for P4 activation by MesTerSn(SitBu3) 2 [blue —] and (MesTer)2Sn [red —] obtained at the DLPNO‐CCSD(T)/def2‐TZVPP//PBE0‐D3/def2‐SVP level of theory and bond lengths, given in Å, as well as HOMO of transition state. Mesityl and tBu substituents as well as hydrogen atoms are omitted for clarity.

Interestingly, on storage of a [D8]THF solution of compound 3 under light for one day, it reverted to the blue‐green color of compound 2. Multinuclear NMR analysis (1H and 31P NMR) suggested the presence of both compounds 3 and 2 in solution, as well as free P4. The conversion of 3 to 2 is further facilitated by using a UV light source with a range of (300–400 nm) with the liberation of P4 observed after 1 h due to the characteristic color change (yellow (3) to blue‐green (2)) and confirmed by multinuclear NMR (31P and 1H). Indeed, time‐dependent DFT (TD‐DFT) calculations corroborate that the transitions to the S2 state (f osc=0.11), experimentally observed at 351 nm (Figure S12), relates to a transition from an essentially Sn‐P4 bonding‐ to a Sn‐P4 antibonding orbital (Figure S17). Whilst quantitative conversion of 3 to 2 was not achieved, even after prolonged irradiation, this study pointed towards the reversible addition of P4 across the SnII center. The low conversion of 3 to 2 is attributed to the facile activation of P4 with 2, as the equilibrium of this reaction (cf. Figure 4) should be entirely on the product side in contrast to (MesTer)2Sn (ΔG=−42 kJ mol−1 vs. −13 kJ mol−1). Additionally, the barrier for activation of P4 is low (ΔG ≠=+86 kJ mol−1), consistent with a fast reaction at room temperature. Notably, compound 2 demonstrates the first example of reversible P−P bond activation with low valent tin compounds.

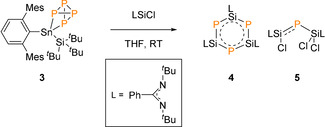

Encouraged by the reversible activation of P4, we were interested to see if 3 could be used as a P4 transfer reagent. In a similar fashion to that reported by Scheer and co‐workers, on treatment of 3 with three equivalent of silylene chloride ([PhC(NtBu)2SiCl]) the yellow solution immediately turned to orange (Scheme 2). [15] The 31P NMR spectrum revealed a mixture of phosphorus containing compounds, however, distinct resonance signals were observed for compound 4 [{PhC(NtBu)2}SiP]3 (crude yield=10 %) and 5 [{PhC(NtBu)2}SiCl}P{SiCl2{PhC(NtBu)2}], at −244.1 and −183.5 ppm, respectively (crude yield=45 %).[ 15 , 16 ]

P4 transfer reaction.

In summary, we have reported for the first time the reversible P‐P bond activation by a heteroleptic stannylene 2. Both experimental and computational investigations revealed the effectiveness of the silyl ligand in order to tune and enhance the reactivity of low valent SnII center. Additionally, transfer of P4 to organic molecules has been demonstrated and further functionalization reactivity is currently under investigation in our lab.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

We are grateful to Dr. Alexander Pöthig and Dr. Shiori Fujimori for crystallographic advice. We gratefully acknowledge financial support from WACKER Chemie AG, the European Research Council (SILION 637394) and the DAAD (fellowship for D.S.). This project has received funding from the European Union's Horizon 2020 research and innovation program under the Marie Skłodowska‐Curie grant agreement No 754462 (Fellowship C.W.). D.M. thanks the RRZ Erlangen for computational resources and the Fonds der chemischen Industrie im Verband der chemischen Industrie e.V. for a Liebig fellowship. Open access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

1

1c

1e

1f

2

3

3a

3a

3b

4

4a

4a

4b

4c

4d

4e

5

5

6

7

8

8b

8c

8e

8f

8g

8g

8h

9

9d

9d

9e

9f

9g

10

10a

10b

10c

11

11a

11b

12

13

13a

13c

13e

14

15