These authors contributed equally to this work.

An effective shielding of both apical positions of a neutral NiII active site is achieved by dibenzosuberyl groups, both attached via the same donors’ N‐aryl group in a C s‐type arrangement. The key aniline building block is accessible in a single step from commercially available dibenzosuberol. This shielding approach suppresses chain transfer and branch formation to such an extent that ultrahigh molecular weight polyethylenes (5×106 g mol−1) are accessible, with a strictly linear microstructure (<0.1 branches/1000C). Key features of this highly active (4.3×105 turnovers h−1) catalyst are an exceptionally facile preparation, thermal robustness (up to 90 °C polymerization temperature), ability for living polymerization and compatibility with THF as a polar reaction medium.

The β‐H elimination event that brings about chain transfer and branch formation in neutral nickel‐catalyzed olefin insertion polymerization is now fully addressed by a C s‐type shielding of both apical positions of a neutral NiII catalyst. Thus, strictly linear (<0.1 brs/1000C) ultrahigh molecular weight polyethylenes (UHMWPEs; 5050 kDa) are now accessible.

Compared to traditional olefin polymerization catalysts based on d0‐metal sites,[ 1 , 2 ] late transition metal catalysts offer benefits such as a tolerance towards polar substrates and reaction media.[ 3 , 4 , 5 , 6 ] Late transition metal complexes are generally prone to β‐hydride elimination (BHE), however. This results in chain transfer and branch formation pathways. To achieve substantial polymer molecular weights, an effective suppression of these pathways that compete with chain growth is essential. Accessing ultrahigh molecular weight polyethylenes[ 7 , 8 ] (UHMWPEs) requires a 105‐fold favoring of chain growth events over chain transfers.

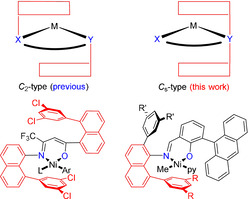

In olefin polymerization with late transition metal NiII and PdII catalysts, high polymer molecular weights are favored by steric shielding of apical positions which hinders chain transfer by associative displacement.[ 9 , 10 , 11 , 12 , 13 , 14 , 15 ] The most efficient way of doing so is arrangement of aryl groups parallel to the square‐planar coordination plane, above and below the active site. Several examples for κ 2‐N,N diimine complexes are based on the principle of a C 2‐type arrangement of the shielding groups, by attaching each shielding group via the substituent framework of one donor.

To transfer this approach to neutral complexes with their unsymmetric κ2‐X,Y‐chelating environment, both different donors’ substitution pattern needs to be suited for attachment of a shielding “lid”. Brookhart and Daugulis solved this elegantly by using enolatoimine complexes most recently (Scheme 1; bottom, left). [16] This approach is not generally applicable to other popular neutral catalyst motifs, however, in which the hard oxygen donor is surrounded by a ligand framework less suitable to achieve C 2‐type shielding. Thus, for the popular and versatile salicylaldiminato motif[ 17 , 18 , 19 , 20 ] so far only a parallel shielding on one side has been achieved, by means of N‐(8‐phenylnaphty‐1‐yl) groups (Scheme 1; bottom, right).[ 21 , 22 ]

C 2‐type arrangement of aryl substituents parallel to the coordination plane (top, left) and C s‐approach pursued in this work (top, right). C 2‐type shielded neutral enolatoimine NiII complex (bottom, left). C 1‐type N‐(8‐phenylnaphty‐1‐yl) salicylaldiminato NiII complex (bottom, right).

We now show how an effective shielding on both apical positions can be achieved by a C s‐type arrangement. This is achieved via readily accessible dibenzosuberyl substituents, and affords strictly linear UHMWPE devoid of any branches.

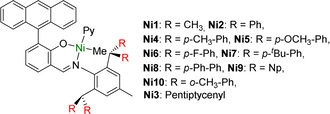

As a reference point, a set of dibenzhydryl[ 23 , 24 ] (Ar2CH‐) substituted salicylaldimines covering a range of steric and electronic properties were generated, and converted to corresponding NiII complexes (Ni2 to Ni10, Scheme 2; for full synthesis and characterization of metal complexes and ligands cf. the Supporting Information, SI). Additionally, the prototypical reference Ni1 was prepared by a reported procedure (Scheme 2). [17]

Reference NiII catalysts studied.

Without addition of any activating cocatalysts, these neutral single‐component NiII catalysts were evaluated for ethylene polymerization under 8 bar at various temperatures. Despite their considerably different steric and electronic substitution patterns, Ni1–Ni10 did not differ dramatically in their catalytic properties (Table 1 and Figure 1; cf. SI for full polymerization data).

Polymer molecular weights produced by Ni1–Ni12 at 30 °C and 90 °C, respectively (8 bar ethylene).

|

Entry |

cat. |

T [°C] |

Yield [g] |

act. [×106][b] |

M n [×104][c] |

M w [×104][c] |

M w/M n [c] |

brs[d] |

T m [e] [°C] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

1 |

Ni1 |

30 |

0.72 |

0.58 |

11.8 |

16.5 |

1.40 |

3 |

129 |

|

2 |

Ni1 |

90 |

0.56 |

0.45 |

0.6 |

0.8 |

1.44 |

63 |

/ |

|

3 |

Ni2 |

30 |

1.94 |

1.55 |

27.3 |

31.9 |

1.17 |

3 |

134 |

|

4 |

Ni2 |

90 |

1.33 |

1.06 |

0.6 |

1.1 |

1.77 |

61 |

81 |

|

5 |

Ni3 |

30 |

0.61 |

0.49 |

8.5 |

12.6 |

1.47 |

3 |

135 |

|

6 |

Ni3 |

90 |

3.31 |

2.65 |

0.4 |

0.4 |

1.15 |

43 |

101 |

|

7 |

Ni4 |

30 |

0.88 |

0.70 |

14.6 |

19.0 |

1.30 |

3 |

134 |

|

8 |

Ni4 |

90 |

2.18 |

1.74 |

0.7 |

1.2 |

1.55 |

65 |

80 |

|

9 |

Ni5 |

30 |

0.63 |

0.50 |

15.0 |

18.2 |

1.21 |

2 |

135 |

|

10 |

Ni5 |

90 |

2.53 |

2.02 |

0.9 |

1.2 |

1.35 |

63 |

79 |

|

11 |

Ni6 |

30 |

0.84 |

0.67 |

17.8 |

22.0 |

1.24 |

3 |

136 |

|

12 |

Ni6 |

90 |

2.32 |

1.86 |

0.6 |

0.9 |

1.46 |

60 |

85 |

|

13 |

Ni7 |

30 |

1.60 |

1.28 |

25.6 |

30.4 |

1.19 |

2 |

133 |

|

14 |

Ni7 |

90 |

2.29 |

1.83 |

0.7 |

1.3 |

1.95 |

62 |

78 |

|

15 |

Ni8 |

30 |

0.83 |

0.66 |

14.3 |

17.7 |

1.24 |

10 |

133 |

|

16 |

Ni8 |

90 |

2.53 |

2.02 |

0.7 |

1.4 |

1.92 |

53 |

85 |

|

17 |

Ni9 |

30 |

0.94 |

0.75 |

14.0 |

18.7 |

1.34 |

6 |

129 |

|

18 |

Ni9 |

90 |

1.22 |

0.98 |

0.3 |

0.5 |

1.48 |

84 |

/ |

|

19 |

Ni10 |

30 |

2.31 |

1.85 |

22.5 |

31.4 |

1.40 |

11 |

118 |

|

20 |

Ni10 |

90 |

0.80 |

0.64 |

1.1 |

1.8 |

1.70 |

55 |

/ |

|

21 |

Ni11 |

30 |

2.93 |

2.34 |

57.4 |

67.2 |

1.17 |

3 |

132 |

|

22 |

Ni11 |

50 |

3.94 |

3.15 |

39.9 |

70.4 |

1.77 |

14 |

123 |

|

23 |

Ni11 |

70 |

1.87 |

1.50 |

32.4 |

53.1 |

1.64 |

23 |

106 |

|

24 |

Ni11 |

90 |

1.65 |

1.32 |

9.5 |

16.9 |

1.78 |

46 |

84 |

|

25 |

Ni12 |

30 |

2.00 |

1.60 |

63.7 |

73.9 |

1.16 |

4 |

128 |

|

26 |

Ni12 |

50 |

1.75 |

1.40 |

44.2 |

71.9 |

1.63 |

17 |

110 |

|

27 |

Ni12 |

70 |

0.95 |

0.76 |

18.5 |

32.8 |

1.77 |

42 |

83 |

|

28 |

Ni12 |

90 |

0.78 |

0.62 |

10.0 |

17.6 |

1.76 |

74 |

/ |

|

29[f] |

Ni11 |

50 |

4.61 |

3.69 |

36.1 |

56.0 |

1.55 |

14 |

118 |

[a] Reaction conditions: Ni catalyst (5 μmol), toluene (100 mL), ethylene (8 bar), polymerization time (15 min), all entries are based on at least two runs, unless noted otherwise. [b] Activity is in unit of 106 g mol−1 h−1. [c] Determined by GPC in 1,2,4‐trichlorobenzene at 150 °C using a light scattering detector. [d] brs=Number of branches per 1000C, as determined by 1H NMR spectroscopy. [e] Determined by DSC (second heating). [f] THF (100 mL) as solvent.

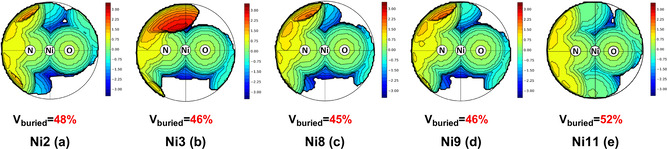

To rationalize these findings, steric maps based on single crystal structures were optimized by a DFT method (BP86‐D3 method, cf. SI for computational details) and the buried volume (Vbur) as a measure of the steric environment around the active NiII site was calculated [25] (Figure 2). Notably, despite their sterically demanding substituents Ni8 (p‐Ph‐Ph) and Ni9 (Np) feature a similar—even slightly lower—Vbur% value than Ni2 (Ph) (45 % and 46 % vs. 48 %).

Steric maps of Ni2, Ni3, Ni8, Ni9, and Ni11 optimized by a DFT computational method (BP86‐D3).

Viewing the substituents in single crystal maps, we find that due to their free rotation, these bulky substituents such as Ph, p‐Ph‐Ph, and Np consistently orient away from the NiII active center (cf. SI. Notably, solution NMR data of Ni2 confirms free rotation of the phenyl groups around the CH‐Ph bond, cf. SI). As a consequence, shielding of the axial sites to retard β‐H elimination is limited. Most notably, the axial sites above and below the square planar coordinated NiII center are not both shielded (Figure 2 a–d).

To appropriately restrict conformational freedom and force an aryl ring into each apical position, we sought to annulate a given dibenzhydryl moieties’ aryl groups to a suitable mutual ring structure. In view of its considerable tension, a seven‐membered ring in the form of a dibenzosuberyl motif [26] was targeted.

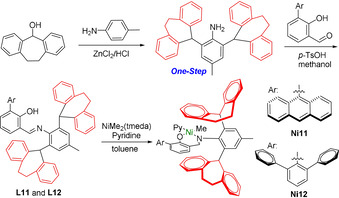

Remarkably, the key 2,6‐disubstituted aniline is accessible in a single step from commercially available compounds in good yield (70 %, Scheme 3). This contrasts the multi‐step synthesis of the aniline component for state‐of‐the‐art N‐terphenyl‐ and N‐8‐arylnaphthyl‐ salicylaldiminato NiII catalysts[ 21 , 22 , 27 , 28 ] (cf. Scheme 1).

Synthesis of C s‐shielded neutral salicylaldiminato NiII catalysts.

Condensation with salicylaldehydes, and reaction with [(tmeda)NiMe2] and pyridine yielded dibenzosuberyl‐based 9‐anthracenyl‐ and meta‐terphenyl‐substituted salicylaldiminato NiII complexes Ni11 and Ni12, respectively (Scheme 3. For full characterization data cf. the SI). Ni11 and Ni12 were undoubtedly corroborated by NMR spectroscopy and elemental analysis. Based on single crystal structure data (cf. SI for details), the buried volume of Ni11 was determined by the aforementioned DFT methods. This yields a significantly higher value compared to the reference cases (V bur% value 52 %). Most significantly, two dibenzosuberyl substituents very effectively shield the axial sites above and below the square planar NiII center (Figure 2 e). This effective shielding by the suberyl aryl groups is also reflected by an upfield 1H NMR resonance of the Ni‐Me moiety (Ni11: −0.93 ppm) relative to the reference catalyst precursors (Ni2: −0.29 ppm). Most notably, in pressure reactor ethylene polymerization experiments with Ni11 and Ni12 yield much higher molecular weights vs. all reference systems (Table 1 and Figure 1).

Ethylene polymerization with Ni11 and Ni12 as single‐component catalyst precursors was studied in more detail (Table 1, entries 21–28 and Table 2). Notably, Ni11 and Ni12 are thermally robust to give a high molecular weight (M w=16.9×104 g mol−1) even at a high polymerization temperature of 90 °C, more than an order of magnitude higher than those produced by Ni1–Ni10 (Figure 1), indicating the effectiveness of our C s‐type shielding strategy.

|

Entry |

T [°C] |

P [bar] |

T [min] |

Yield [g] |

act. [×106][b] |

M n [×104][c] |

M w [×104][c] |

M w/M n [c] |

brs[d] |

T m [e] [°C] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

1[f] |

30 |

8 |

5 |

0.31 |

2.19 |

22.3 |

25.5 |

1.15 |

3.5 |

131/135 |

|

2[f] |

30 |

8 |

10 |

0.60 |

2.12 |

39.5 |

45.4 |

1.15 |

2.9 |

133/136 |

|

3[f] |

30 |

8 |

15 |

0.91 |

2.14 |

57.8 |

69.5 |

1.20 |

2.7 |

133/138 |

|

4[f] |

30 |

8 |

20 |

1.09 |

1.92 |

70.9 |

86.5 |

1.22 |

2.9 |

132/ 138 |

|

5[g] |

30 |

30 |

15 |

2.61 |

6.96 |

208.7 |

242.3 |

1.16 |

0.2[k] |

136/ 144 |

|

6[h] |

30 |

40 |

15 |

2.26 |

12.05 |

248.9 |

372.2 |

1.50 |

0.1[k] |

134/142 |

|

7[h] |

30 |

40 |

60 |

2.95 |

3.93 |

304.7 |

505.1 |

1.66 |

<0.1[k] |

135/144 |

|

8[i] |

90 |

30 |

15 |

2.94 |

3.92 |

21.1 |

31.8 |

1.51 |

29 |

99/106 |

|

9[i] |

90 |

40 |

15 |

3.70 |

4.93 |

22.4 |

34.1 |

1.52 |

28 |

101/106 |

|

10[h,j] |

30 |

40 |

60 |

2.31 |

3.08 |

141.3 |

202.0 |

1.43 |

0.3[k] |

135/143 |

[a] Reaction conditions: toluene (100 mL), all entries are based on at least two runs, unless noted otherwise. [b] Activity is in unit of 106 g mol−1 h−1. [c] Determined by GPC in 1,2,4‐trichlorobenzene at 150 °C using a light scattering detector. [d] brs=Number of branches per 1000C, as determined by 1H NMR spectroscopy. [e] Determined by DSC at 10 K min−1 (second heating/ first heating). [f] Ni11 (1.7 μmol). [g] Ni11 (1.5 μmol). [h] Ni11 (0.75 μmol). [i] Ni11 (3 μmol). [j] THF (100 mL). [k] brs=Number of branches per 1000C, as determined by 13C NMR spectroscopy.

Compared to these polymerizations in toluene, catalytic activity is even higher in tetrahydrofuran (THF) as a polar reaction medium, although molecular weight decreases slightly (Table 1, entries 22 vs. 29). Remarkably, polymerization even occurs in this challenging reaction medium—which is not compatible with early transition metal and also many late metal polymerization catalysts[ 3 , 4 , 5 , 6 , 20 ]—to high molecular weight polymer (Table 2).

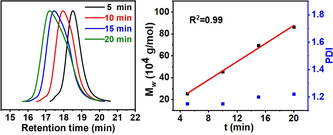

The polymerization to high molecular weight polyethylenes proceeds in a living fashion at 30 °C and 8 bar (Table 2, entries 1–4). Both yield and molecular weight increase linearly with polymerization time (Figure 3). Within 20 min M w=86.5×104 g mol−1 is reached. Notably, polymer precipitation during the reaction possibly has a small effect on molecular weight distributions.

Living nature of ethylene polymerization with Ni11 at 30 °C (Table 2, entries 1–4).

Polymerization at higher 40 bar ethylene pressure results in remarkably higher catalyst activities (TOF: 4.3×105 h−1) and molecular weights well in the ultrahigh molecular weight regime (M w: 3.7×106 g mol−1), while branching is further reduced to only 0.1/1000C (Table 2, entry 6). This compares favorably with the state‐of‐the‐art neutral NiII catalysts[ 16 , 21 , 28 ] and other catalysts.[ 29 , 30 , 31 , 32 ]

Due to the triple characteristics of high activity, low degree of branching, and ultrahigh molecular weight, rapid precipitation of the product polymer occurred during polymerization, which may impact the reaction. Thus, an even lower catalyst loading of 7.5×10−7 mol was explored. Notably, despite the absence of any alkyl aluminum cocatalysts or scavenger, polymerization performance is retained (Table 2, entries 6 and 7). At a prolonged reaction time of 1 h UHWMPE with M w of 5.1×106 g mol−1 (M n: 3.1×106 g mol−1) is formed. Most importantly, the degree of branching is below the detection limit (<0.1/1000C) (Figure 4, Table 2, entry 7). This is also reflected in a very high melting point (T m) of up to 144 °C. As anticipated, higher ethylene pressure of 30 bar and 40 bar at challenging 90 °C resulted in elevated activities and enhanced molecular weights (M w: 3.4×105 g mol−1) (Table 2, entries 8 and 9). Most notably, in THF as a reaction medium Ni11 even enabled the formation of linear UHMWPE (M w: 2.0×106 g mol−1; 0.3 branches/1000C) at 40 bar (Table 2, entry 10).

Ni11 was also capable of promoting copolymerization of ethylene and ester‐functionalized undecylenic acid methyl ester (cf. SI, Table S2). Studies at various temperatures from 30 °C to 90 °C gave copolymers with high molecular weights (3.9 to 26.4×104 g mol−1), tunable degrees of branching (4 to 28/1000C), and reasonable incorporations of comonomer (0.2 to 1.5 mol %).

In summary, the approach reported enables an effective shielding of both apical positions of a square‐planar coordinated active metal site, through a C s‐type arrangement of both shielding groups by attachment via the same N‐donor atoms’ framework. This overcomes the general propensity of late transition metal catalysts for β‐H elimination, and hinders chain transfer and branching pathways very effectively, as evidenced by a living nature of the polymerization and the formation of strictly linear ultrahigh molecular weight polyethylene. Such a microstructure is desirable for this important material, but difficult to access, particularly with late transition metal catalysts. Notably, these novel catalysts are also thermally robust and tolerant to polar reaction media. At the same time, this novel type of shielding is easily accessible. The key aniline building block is formed from commercially available compounds in a single step, with good yield. Thus, this chemistry provides broader perspectives for polymerization catalysis and beyond.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Z.J. and X.K. are thankful for financial support from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Nos. 21871250 and 21704011), the Jilin Provincial Science and Technology Department Program (No. 20200801009GH). Open access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

2

2

5

5

6

6

7

8

9

10

10

11

12

13

14

15

17

18

18

19

21

25

26

27

27

30

31

31