These authors contributed equally to this work.

The dinickel(II) dihydride complex (1K) of a pyrazolate‐based compartmental ligand with β‐diketiminato (nacnac) chelate arms (L−), providing two pincer‐type {N3} binding pockets, has been reported to readily eliminate H2 and to serve as a masked dinickel(I) species. Discrete dinickel(I) complexes (2Na, 2K) of L− are now synthesized via a direct reduction route. They feature two adjacent T‐shaped metalloradicals that are antiferromagnetically coupled, giving an S=0 ground state. The two singly occupied local dx2-y2 type magnetic orbitals are oriented into the bimetallic cleft, enabling metal–metal cooperative 2 e− substrate reductions as shown by the rapid reaction with H2 or O2. X‐ray crystallography reveals distinctly different positions of the K+ in 1K and 2K, suggesting a stabilizing interaction of K+ with the dihydride unit in 1K. H2 release from 1K is triggered by peripheral γ‐C protonation at the nacnac subunits, which DFT calculations show lowers the barrier for reductive H2 elimination from the bimetallic cleft.

Highly reactive dinickel(I) complexes with an open cleft between two “T”‐shaped metalloradicals are accessible via H2 release from a dinickel(II) dihydride complex based on a pyrazolate/β‐diketiminato hybrid ligand. The barrier to intramolecular H2 elimination is drastically lowered by protonation at the ligand periphery.

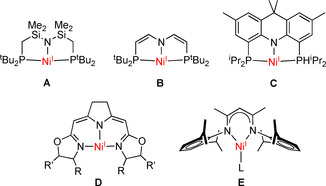

Nickel(I) complexes, while long considered rare and rather unstable, [1] are currently receiving much attention. [2] This is motivated not only by the mechanistic relevance of nickel(I) in some metalloprotein active sites (such as the cofactor F430 in methylcoenzyme M reductase or the Ni/Fe/S cofactor of acetyl coenzyme A synthase), but also by the increasing use of nickel(I) complexes in catalysis, most prominently in cross‐coupling chemistry and in the reductive activation of small molecules.[ 3 , 4 ] For the latter, three‐coordinate nickel(I) complexes with a “T”‐shaped structure appear particularly promising, as they expose a reactive binding site with d9 metalloradical character, with the unpaired electron residing in the accessible σ‐antibonding orbital. This specific geometry can be enforced by pincer‐type ligands, but structurally characterized systems are still rare; some prominent examples, A–D, are shown in Figure 1.[ 5 , 6 , 7 , 8 ] In contrast, β‐diketiminato (nacnac) ligands with bulky N‐substituents (E), which are most commonly employed in this field, usually give rise to the sterically more favored “Y”‐shaped structures.[ 9 , 10 , 11 , 12 ] While all the above ligands generally form mononuclear nickel(I) complexes, Yoo and Lee recently pointed out that bimetallic versions of based metalloradicals would be highly desirable for enabling two‐electron transformations via metal‐metal cooperativity (MMC). [7] This is well reflected in the various reactivities of complexes A–E that ultimately give dinickel(II) products composed of two {LNi} subunits;[ 3 , 4 , 7 ] however, binucleating scaffolds that preorganize two d9 nickel(I) ions in a suitable arrangement for cooperative bimetallic chemistry are lacking. [13]

Prominent examples of the few “T”‐shaped NiI complexes that have been structurally characterized by X‐ray diffraction (see text for references).

As most reductive transformations of small molecules (such as CO2, N2, etc.) involve the synchronized transfer of electron and protons, metal ligand cooperativity (MLC) exploiting proton transfer sites on the ligand has emerged a powerful concept [14] and has been well established for pincer scaffolds with N/NH groups in the backbone. [15] Non‐innocence of β‐diketiminato ligands at the γ‐C atom has also been demonstrated, though it mostly involves oxygenative ligand modifications [16] or metal‐ligand cross additions, while backbone protonation for enhancing the utility of nacnac complexes is relatively rare. [17]

We recently reported binucleating bis(tridentate) ligands that have two β‐diketiminato compartments appended to a central pyrazolate bridge. [18] The dinickel(II) dihydride complexes 1K and 1′, which are conveniently prepared from the dinickel(II) precursor LNiII 2Br and KBEt3H (Scheme 1), [18a] can be described as masked dinickel(I) synthons as they were shown to smoothly eliminate H2 in the presence of substrates, enabling the two‐electron reductive binding of various small molecules within the bimetallic cleft.[ 18 , 19 ] Intramolecular H2 elimination is facile in case of 1′ at room temperature even in the absence of substrates, but has a much higher barrier in case of K+‐stabilized 1K. [18a] The headspace GC/MS detection of H2 released from solid samples of 1′ and in situ monitoring of the sample by SQUID magnetometry provided evidence for the formation of a highly reactive dinickel(I) intermediate 2′. [18a]

![Overview of reactions towards dinickel(I) complexes studied in Ref. [18a] and in this work.](/dataresources/secured/content-1765935906202-30df4269-11e8-442a-8fb8-6e865248fa63/assets/ANIE-60-1891-g009.jpg)

Overview of reactions towards dinickel(I) complexes studied in Ref. [18a] and in this work.

Because of the topology of the two pincer‐type {N3} binding compartments of L−, complex 2′ was expected to feature two adjacent “T”‐shaped nickel(I) subunits. The current work aimed at isolating and characterizing 2′ and at accessing such dinickel(I) complex of the binucleating β‐diketiminato/pyrazolato hybrid ligand directly from LNi2Br. During the course of these studies, it was found that H2 release from 1K can be triggered by peripheral ligand protonation to give an unprecedented double “T”‐shaped dinickel(I) complex that bears the potential of combining MMC and MLC reactivity in a bimetallic system.

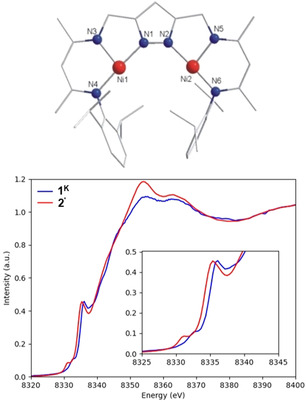

Attempts to crystallize the dinickel(I) complex 2′, prepared by keeping samples of 1′ under vacuum for one day, yielded red crystals from THF/hexane. Unfortunately, despite many attempts the crystal quality of 2′ was only moderate, and insufficient for a neutron diffraction study. While X‐ray diffraction (XRD) clearly confirmed the {LNi2} core structure, the absence or presence of hydride ligand within the bimetallic pocket could not be ascertained. A DFT optimized structure of the cation of 2′ (B3LYP‐D3/def2‐SVP; Figure 2 a) indicated that all metric parameters are very similar in 1′ and 2′. However, an NMR spectrum of the red product 2′ in [D8]THF showed paramagnetism, and the Ni‐H stretch at 1907 cm−1 characteristic for 1′ [18a] is absent in the IR spectrum of solid 2′ (Figure S3). The nickel(I) character of 2′ was confirmed by X‐ray absorption spectroscopy (XAS) (Figure 2 b). Figure S40 shows the calculated Ni pre‐edge spectra of complexes 1K and 2′ compared with the experimental data. Difference densities provide a depiction of the spatial distribution of the core excited electrons, and for complexes 1K and 2′ they are distributed in the equatorial plane of the complex and reveal that the pre‐edge features are due to the 1s→ transition. The calculated spectra show a ≈1.3 eV decrease in pre‐edge energy on going from complex 1K to 2′, which is in good agreement with the observed shift in the experimental pre‐edge energies, corroborating that 2′ is a nickel(I) species.

Top: DFT‐optimized structure of the anion of 2′ (B3LYP‐D3/def2‐SVP level). Hydrogen atoms are omitted for clarity. Bottom: Normalized Ni K‐edge XAS spectra of complexes 1K and 2′. The inset shows the low‐energy features in the pre‐edge and rising edge regions of the spectra.

An alternative synthetic route to obtain a {LNiI 2} species directly, circumventing the dihydride intermediate, could now be established by treating the precursor complex LNi2Br with strong reducing agents such as KC8 or sodium naphthalenide in THF. Single crystals of highly air and moisture sensitive 2M (M=Na or K) suitable for X‐ray diffraction were obtained by layering THF solutions of the products with hexane/Et2O at −30 °C and after several recrystallizations; the molecular structure of 2K is shown in Figure 3(see SI for the structure of 2Na and for crystallographic details as well as a complete list of bond lengths and angles). It confirms the presence of two NNN‐based “T”‐shaped nickel(I) subunits that are spanned by the pyrazolate with d(Ni⋅⋅⋅Ni)=4.1243(7) Å and with angles N1‐Ni1‐N4 and N2‐Ni2‐N6 very close to 180° (viz. 176.8(1) and 176.2(1)°). Comparison of the molecular structures of K[LNiI 2] (2K) and K[L(NiII‐H)2] (1K) shows that the most conspicuous difference is the position of the K+ cation: In 1K the K+ is located within the plane defined by the pyrazolate‐bridged dinickel dihydride core and in between the two flanking aryl rings of the 2,6‐disopropylphenyl (dipp) substituents at distances indicative of cation‐π interactions. [18a] In contrast, in 2K the K+ is located above the pyrazolate [20] and is additionally ligated by four THF molecules (the structure of 2Na is very similar, but the Na+ has only two THF ligands; Figure S9). This striking difference may reflect attractive K+⋅⋅⋅hydride interactions in 1K that are now absent in the double “T”‐shaped dinickel(I) complex 2K, in line with the stabilizing role of K+ with respect to H2 elimination from 1K which has a much higher activation barrier than H2 elimination from 1′.

![Molecular structure of 2K (30 % probability thermal ellipsoids). K+⋅⋅⋅Cpz contacts <3.5 Å are shown as dashed lines.

[24]](/dataresources/secured/content-1765935906202-30df4269-11e8-442a-8fb8-6e865248fa63/assets/ANIE-60-1891-g003.jpg)

Molecular structure of 2K (30 % probability thermal ellipsoids). K+⋅⋅⋅Cpz contacts <3.5 Å are shown as dashed lines. [24]

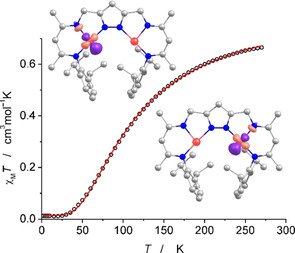

The dinickel(I) character of 2K (and 2Na) was confirmed by magnetic susceptibility measurements (Figure 4; see SI for details). SQUID data for a sample of crystalline material of 2K show a χ M T value of 0.66 cm3 mol−1 K at 270 K and a decrease of χ M T upon lowering the temperature, approaching zero below 30 K. This reflects significant antiferromagnetic coupling and an S T=0 ground state. Analysis of the magnetic data using a dimer model with two coupled S= spin centers (Ĥ=−2 J Ŝ 1 Ŝ 2 Hamiltonian; see SI for details) gave J=−71 cm−1 (g=2.14), in excellent agreement with J=−69.5 cm−1 derived from the magnetic data of 2′ that was prepared by keeping crystals of 1′ under vacuum for 15 h. [18a] Antiferromagnetic coupling is slightly stronger in 2Na (J=−83 cm−1; see Figure S8), which may be related to the more planar pyrazolato‐based dinickel(I) core: the torsion angle Ni(1)‐N(1)‐N(2)‐Ni(2) is 4.9° in 2Na versus 18.2° in 2K. Note that the M‐Npz‐Npz‐M torsion has previously been shown to have a strong effect on the magnetic coupling in pyrazolato‐bridged complexes of two S= metal ions M, [21] and the coupling may even become ferromagnetic in orthogonal situations when the torsion approaches 90°. [22]

Distances and angles of the DFT optimized structures of [LNi2]− (viz. the anion of 2M and 2′) are in good agreement with metric parameters observed experimentally (Table S3). Energies of the S=1 and the antiferromagnetically coupled broken symmetry state differ by less than 0.2 kcal mol−1 (Table S5) and optimized structures are almost identical. A single point calculation based on the atomic coordinates taken from the X‐ray crystallographic analysis of 2K confirms an antiferromagnetically coupled ground state (J≈−100 cm−1; Table S5). According to a Löwdin spin population analysis 87 % of the spin density is located on the nickel ions (a spin density plot is shown in Figure S19). The magnetic orbitals (from unrestricted corresponding orbitals; see inset in Figure 4) have mainly nickel d character, viz. ≈70 % according to Löwdin reduced orbital populations per MO, with only minor contributions from nickel s‐ and p‐orbitals (<10 %). The small calculated overlap (0.05) of the corresponding orbitals is in agreement with weak antiferromagnetic coupling. [23]

χ M T versus T plot for 2K; the solid red line is the calculated curve fit (Ĥ=−2 J Ŝ 1 Ŝ 2 with J=−71 cm−1 and g=2.14). The insets show the magnetic orbitals according to DFT calculations (see text and Supporting Information for details).

The magnetic orbitals of [LNi2]− are best described as the local σ‐antibonding orbitals of the metalloradical subunits, similar to the SOMO in mononuclear T‐shaped nickel(I) complexes. [7] In [LNi2]− these half‐filled orbitals are oriented into the bimetallic cleft, suggesting that metal‐metal cooperative 2 e− substrate transformations within the cleft should be facile. Indeed, 2K smoothly reacts with H2 to give 1K via homolytic σ‐bond cleavage (see Scheme 1), and it rapidly reacts with O2 to give the μ1,2‐peroxo complex [KLNi2(O2)]. [19a]

To probe whether H2 release from the K+‐stabilized dihydride complex 1K can be induced by protonation, a THF solution of 1K was treated with [H(OEt2)2]BArF 4. This causes an immediate color change of the solution from orange to brown‐red, accompanied by gas evolution. Single crystals of the highly air and moisture sensitive product 3 were obtained by layering the THF solution with hexane/Et2O at −30 °C. The molecular structure of the cation of 3 determined by X‐ray diffraction is shown in Figure 5 (see SI for further details). In 3, the two nickel ions are again found tricoordinate in nearly perfect “T”‐shaped geometry (N‐Ni‐N angles of 84.6°, 97.0° and 177.9° at Ni1 and 84.6°, 96.5° and 178.0° at Ni2) at a distance of d(Ni⋅⋅⋅Ni)=4.1032(5) Å. Both nacnac parts are protonated at the γ‐C atoms, and the presence of two β‐diimine subunits in [LH2NiI 2]+ (cation of 3) is evidenced by short C=N bonds (average 1.285(3) Å in 3 vs. 1.330(3) Å in 1K or 1.332(5) Å in 2K) and by a characteristic C=N stretch at 1670 cm−1 in the IR spectrum.

![Molecular structure of [LH2NiI

2]+ (cation of 3; thermal ellipsoids set at 30 % probability). The BArF

4 counteranion and most hydrogen atoms (except for those at the γ‐C of the β‐diimine subunits) are omitted for clarity.

[24]](/dataresources/secured/content-1765935906202-30df4269-11e8-442a-8fb8-6e865248fa63/assets/ANIE-60-1891-g005.jpg)

Molecular structure of [LH2NiI 2]+ (cation of 3; thermal ellipsoids set at 30 % probability). The BArF 4 counteranion and most hydrogen atoms (except for those at the γ‐C of the β‐diimine subunits) are omitted for clarity. [24]

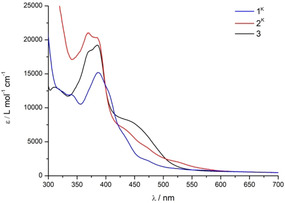

A DFT optimized structure of [LH2NiI 2]+ reproduces well the experimentally determined metric parameters of the cation of 3 (Table S4), and the computational results indicate an S=0 ground state with antiferromagnetic coupling of the same magnitude as in [LNi2]− (Table S5). UV‐vis spectra of 2K, 2Na and 3 in THF show quite intense bands in the range 350–400 nm typical for all dinickel complexes of the binucleating ligand L−. The present dinickel(I) complexes show broad low‐energy shoulders around 450 nm, and 2K features an additional weak absorption around 520 nm (Figure 6). According to TD‐DFT computations these absorptions at lower energy beyond 420 nm are mostly assigned to metal to ligand charge transfer (MLCT) transitions involving the nacnac or β‐diimine parts of the ligand, respectively.

UV/Vis spectra of dinickel(II) complex 1K and dinickel(I) complexes 2K and 3 in THF at room temperature.

When the dideuteride analogue of 2K, [KL(NiII‐D)2] (1K‐D), was protonated with 2 equivalents of [H(Et2O)2]BArF 4 in THF and the reaction monitored by 2H NMR spectroscopy, clean formation of D2 was detected, without any signs of HD (Figure 7). This shows that only the Ni‐bound hydride (deuteride) ligands are released, and it suggests that protonation at the peripheral γ‐C atoms triggers intramolecular reductive elimination of H2 (D2) from the bimetallic cleft.

![2H NMR spectrum (77 MHz) of a solution of 1K‐D in THF (bottom) and after addition of 2 equivalents of [H(Et2O)2]BArF

4 (top); solvent signals are marked with an asterisk.](/dataresources/secured/content-1765935906202-30df4269-11e8-442a-8fb8-6e865248fa63/assets/ANIE-60-1891-g007.jpg)

2H NMR spectrum (77 MHz) of a solution of 1K‐D in THF (bottom) and after addition of 2 equivalents of [H(Et2O)2]BArF 4 (top); solvent signals are marked with an asterisk.

The paths to reductive H2 release were then computed with and without protonation of the peripheral ligand, starting from the structures of the anion 1′ and the hypothetical dihydride of 3, [LH2(Ni‐H)2]+ (3′); the results are depicted in Figure 8 a. By bringing the two hydrogen atoms closer together in a constrained optimization path, one crosses from the dihydride (MIN1) to a pre‐dissociated state (MIN2), separated by a small barrier (TS1). As in the previous report on 1K and 1′, [18a] we estimate the last barrier to H2 release from the bimetallic cleft with the equilibrium dihydrogen H‐H distance at the same level of theory (TS2*). An energy plateau MIN2 is observed (viz., formation of the dihydrogen bond). One notable difference between 1′ and 3′ is the depth of MIN2, which is significantly stabilized upon protonation of the nacnac‐type ligand subunits. At the level of theory used, this minimum is as stable as the starting dihydride complex (MIN1). The TS2 barrier towards final H2 release is also significantly reduced upon peripheral ligand protonation (from about 55 to 37 kJ mol−1). When considering the same pathways with a K+ cation in the pocket, H2 release is again favored in the case of 3K′ compared to 1K. In this case a new factor comes into play: the added flexibility of the protonated ligand [LH2]− upon loss of the conjugation in the β‐diimine subunits. The tridentate pincers can now move above the plane with the cation, opening a path for H2 to leave the complex. We show a comparison of the two computed minima structures of 1K and 3K′ in Figures 8 b and c, respectively, where the effect is clearly visible.

![a) Computed reaction paths (electronic energies) for H2 release. The numbers above the bars indicate the H–H distance at each stationary point. TS2* is an approximation to the barrier for hydrogen release, obtained by performing a constrained optimization at the equilibrium dihydrogen distance (see Supporting Information). The optimized structures of b) 1K and c) [LH2(Ni‐H)2K]2+ (cation of 3K′). Both the leaving hydrogen atoms and the ones at the γ‐C of the β‐diimine subunits are shown as bright green sticks.](/dataresources/secured/content-1765935906202-30df4269-11e8-442a-8fb8-6e865248fa63/assets/ANIE-60-1891-g008.jpg)

a) Computed reaction paths (electronic energies) for H2 release. The numbers above the bars indicate the H–H distance at each stationary point. TS2* is an approximation to the barrier for hydrogen release, obtained by performing a constrained optimization at the equilibrium dihydrogen distance (see Supporting Information). The optimized structures of b) 1K and c) [LH2(Ni‐H)2K]2+ (cation of 3K′). Both the leaving hydrogen atoms and the ones at the γ‐C of the β‐diimine subunits are shown as bright green sticks.

In conclusion, using a pyrazolate‐based ligand scaffold that provides two pincer‐type {N3} binding compartments a relatively stable dinickel(I) complex featuring two adjacent T‐shaped metalloradicals has been isolated and comprehensively characterized, including magnetic measurements that reveal moderate antiferromagnetic coupling and an S=0 ground state. The two singly occupied type magnetic orbitals of the d9 nickel(I) subunits are quite exposed and both oriented into the bimetallic cleft, which promises rich metal‐metal cooperative 2 e− chemistry as evidenced by the rapid reaction of 2K with H2 or O2 to give the dinickel(II) dihydride or dinickel(II) peroxide species [KL(Ni‐H)2] (1K) and [KLNi2(O2)], respectively. Pincer‐based T‐shaped nickel(I) metalloradicals have recently been shown to serve as powerful reductants for challenging substrate activations,[ 3 , 4 , 6 , 7 ] and the present system now provides a highly preorganized dinuclear variant that can capture 2 e−‐reduced substrates within its bimetallic pocket. Interestingly, the molecular structures of [KL(NiII‐H)2] (1K) and [KL(NiI)2] (2K) differ by the position of the K+ cation, supporting a stabilizing effect of the K+ on the dihydride unit. We have previously reported that dinickel(II) dihydride complexes 1K and 1′ serve as masked synthons for a highly reactive dinickel(I) species, [18] and it is now demonstrated that dehydrogenation can be triggered by peripheral ligand protonation, which drastically lowers the barrier for reductive H2 elimination from the bimetallic cleft. This finding also emphasizes the non‐innocence of nacnac ligands in terms of metal‐ligand cooperativity. It is an exciting perspective that [LH2NiI 2]+ (3) offers not only two e− (as a highly reactive dimetallodiradical), but also two H+ (stored at the ligand periphery) to potentially mediate coupled 2 e−/2 H+ substrate transformations. Work in this direction is in progress in our laboratory.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Support from the China Scholarship Council (Ph.D. fellowship for P.‐C.D.) and the University of Göttingen (F.M.) is gratefully acknowledged. S.DeBeer acknowledges the Max Planck Society for financial support. This project has been partly funded by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG, German Research Foundation)—project number 405832858 (computing cluster) and 423268549 (X‐ray diffractometer). Use of the Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Lightsource, SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory, is supported by the U.S. Department of Energy, Office of Science, Office of Basic Energy Sciences under Contract No. DE‐AC02‐76SF00515. The SSRL Structural Molecular Biology Program is supported by the DOE Office of Biological and Environmental Research, and by the National Institutes of Health, National Institute of General Medical Sciences (P41GM103393). Open access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

1

5

6

7

7

8

9

9a

10

11

12

12a

12c

12d

13

14

14a

14a

15

15a

16

16

18

18a

19

19a

19b

19b

20

20

21

22

22a

22a

22b

22b

23

24