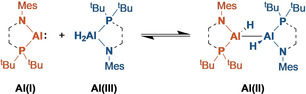

Oxidative addition and reductive elimination are defining reactions of transition‐metal organometallic chemistry. In main‐group chemistry, oxidative addition is now well‐established but reductive elimination reactions are not yet general in the same way. Herein, we report dihydrodialanes supported by amidophosphine ligands. The ligand serves as a stereochemical reporter for reversible reductive elimination/oxidative addition chemistry involving AlI and AlIII intermediates.

Low‐oxidation‐state main‐group compounds exhibit rich oxidative addition chemistry. The same is not true for the reverse process, reductive elimination. Put together, the processes enable numerous catalytic cycles in transition‐metal chemistry. Here, using a stereoactive ligand as a reporter, it is revealed that AlII dihydrodialanes exhibit transition‐metal‐like reversible reductive elimination. Mes=2,4,6‐trimethylphenyl.

Oxidative addition to aluminum(I) compounds is now well established, but examples of reductive elimination from AlIII to AlI—and strategies to engineer it—are much scarcer.

AlI compounds can be broadly divided into neutral and anionic classes. Of the neutral compounds, oxidative addition of E‐H and E‐X bonds has been reported for (Cp*Al)4 (I, Figure 1), [1] bulkier derivatives, [2] and for NacNacAl(I) (II). [3] More recently, several anionic AlI compounds have been reported. Starting with the dimeric precursor to IV, [4] several AlI compounds supported by diamido ligands have been prepared. [5] Diverging from diamides, mixed amido/alkyl [6] and dialkyl [7] AlI anions are now also known. Unsurprisingly, the anionic systems are even more reactive than the neutral compounds and also exhibit oxidative addition chemistry.

![Selected neutral and anionic aluminum(I) and aluminum(II) compounds exhibiting (reversible) reductive elimination/oxidative addition behaviour. Dipp=2,6‐diisopropylphenyl. (2,2,2)cryptand=4,7,13,16,21,24‐hexaoxa‐1,10‐diazabicyclo[8.8.8]hexacosane.](/dataresources/secured/content-1765934612986-a5d85e46-91a2-4bbe-beeb-857a5c55accd/assets/ANIE-60-2047-g001.jpg)

Selected neutral and anionic aluminum(I) and aluminum(II) compounds exhibiting (reversible) reductive elimination/oxidative addition behaviour. Dipp=2,6‐diisopropylphenyl. (2,2,2)cryptand=4,7,13,16,21,24‐hexaoxa‐1,10‐diazabicyclo[8.8.8]hexacosane.

Reductive elimination chemistry at aluminum is much less developed. This is unsurprising considering the lower stability of the AlI oxidation state compared to AlIII. Nevertheless, there are notable examples of reductive elimination from AlIII. Cp*2AlH reversibly reductively eliminates Cp*H to form Cp*Al, I.[ 1b , 8 ] DippNacNacAlH2 undergoes reversible oxidative addition to DippNacNacAl(I), II, though the product III has not been isolated (DippNacNac =(DippNCMe)2CH). [9] Most remarkably, the monomeric AlI anion IV reversibly inserts into the C−C bond of benzene (by oxidative addition). [10]

A notable characteristic of main‐group systems is that base‐coordination can induce reductive elimination. For example, treating Si2Cl6 with Lewis bases induces reductive elimination, to form SiCl4 and base‐coordinated SiCl2. [11] Similar reactivity was recently reported for the dialane V, which disproportionates to AII and AlIII fragments upon treatment with Lewis bases. [12]

We have reported AlIII dihydrides 1 a and 1 b supported by mixed‐donor N/P ligands that exhibit flexible coordination behavior. [13] Notably, the same ligand class was used by Kato to mediate reversible oxidative addition to SiII compounds. [14] We thus wondered whether the amidophosphine ligands of 1 a and 1 b might prime AlII systems for reductive elimination.

The study of dialanes—AlII compounds—predates most work on AlI. Dialanes are prone to disproportionation to Al0 and AlIII, but this can be avoided using bulky substituents. [15]

Despite the useful and extensive reactivity of aluminum(III) hydrides, [16] there are scant examples of AlII hydrides. Jones has reported the NHC‐coordinated parent dialane Al2H4 as well as amidinato‐ and guanadinato‐coordinated dihydrodialanes. [17] The reactivity of these compounds has not been explored.

Here, we report the reversible reductive elimination reactivity of dihydrodialanes supported by amidophosphine ligands. The complex stereochemistry of the N/P ligand enables the detection of “hidden” reductive elimination processes by revealing the interconversion of multiple diastereomers by reversible reductive elimination.

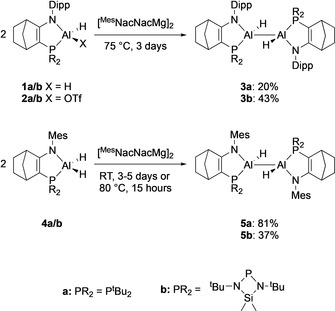

We initially prepared the dihydrodialanes 3 a and 3 b by reduction of AlIII dihydrides 1 a and 1 b (Scheme 1). [13] Jones et al. used MgI reducing agents to access hydride‐substituted dialanes. [17] Accordingly, treatment of 1 a or 1 b with [MesNacNacMg]2 [18] forms the AlII dihydrido dialanes 3 a and 3 b, alongside the expected MgII hydride. The formation of 3 a and 3 b was slow (2–4 days at 70 °C) and limited quantities of starting material were converted (1 a: 22 %, 1 b: 12 %). In practice, the dialanes 3 a and 3 b are accessed in better yields from reduction of the OTf substituted AlIII hydrides 2 a and 2 b, which leads to good conversion to 3 a and 3 b (3 a 43 %, 3 b 78 %) and acceptable isolated yields (3 a 20 %, 3 b 43 %).

Reductions of AlIII hydrides 1, 2 and 4 to form AlII dihydrodialanes 3 and 5. Dipp=2,6‐diisopropylphenyl. Mes=2,4,6‐trimethylphenyl.

Reducing instead AlIII dihydrides with decreased steric bulk at the nitrogen center—4 a and 4 b—further improves the reaction. The reduction to the dialanes 5 a and 5 b proceeds smoothly with quantitative conversion and in good yields (5 a 81 %; 5 b 37 %).

The AlII dihydrodialanes 3 and 5 are structurally very similar. X‐ray crystallography reveals the expected four‐coordinate tetrahedral geometry at the aluminum centers, which are κ2‐coordinated by the amidophosphine ligands. Although the parent dialane Al2H4 is predicted to favor hydride‐bridged structures, [19] base coordination induces H2Al‐AlH2 connectivity and terminal hydrides. [17] Thus, crystallography reveals terminal hydride substituents; this is consistent with the observed infrared terminal Al‐H stretches which, as would be expected, are at lower wavenumber than the dihydride precursors (e.g. 5: 1688–1725 cm−1; 4: 1795–1802 cm−1).[ 17 , 19 ] In all of the structures, stereocenters at aluminum and in the ligand lead to crystallographic disorder in the norbornene backbone due to co‐crystallization of multiple diastereomers (see later). We also note that in solving the structure of 5 a (Figure 2) we identified a cocrystallized minor component with a substantially shorter Al‐Al distance than 5 a. [20]

![X‐ray crystal structure of 5 a (ligand hydrogen atoms omitted). Thermal ellipsoids at 50 % probability. Only the major component of the disordered ligand is shown (5 a‐B).

[24]](/dataresources/secured/content-1765934612986-a5d85e46-91a2-4bbe-beeb-857a5c55accd/assets/ANIE-60-2047-g002.jpg)

X‐ray crystal structure of 5 a (ligand hydrogen atoms omitted). Thermal ellipsoids at 50 % probability. Only the major component of the disordered ligand is shown (5 a‐B). [24]

Unsurprisingly, increasing the steric bulk at the nitrogen or phosphorus centers increases N‐Al and P‐Al distances (Table 1). The Al−Al bond distances follow the same general trend, though the Al−Al bond distance in the N‐mesityl dialane 5 b is longer than in its Dipp counterpart 3 b (2.886(2) vs. 2.8386(18) Å).

|

|

Al‐Al′ |

N‐Al |

P‐Al |

N‐Al‐P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

3 a N(Dipp)/PtBu2 |

2.7323(19) |

1.927(2) |

2.4977(11) |

85.12(7) |

|

3 b N(Dipp)/PN2Si |

2.8386(18) |

1.939(2) |

2.4982(10) |

85.06(7) |

|

5 a N(Mes)/PtBu2 |

2.6586(16) |

1.918(2) |

2.4677(9) |

85.86(6) |

|

5 b N(Mes)/PN2Si |

2.886(2) |

1.911(3) |

2.4671(11) |

86.51(8) |

The Al‐Al bond distances in 3 and 5 are remarkably long. The shortest distance is found in 5 a, which at 2.6585(16) Å is close to reported amidinato aluminum(II) hydride dimers (2.57–2.67 Å). [17] The Al‐Al distances in 3 b and 5 b are much longer than any previously reported for 3‐ or 4‐coordinate dialanes, including that of the dialane(4) [(tBu3Si)2Al]2 (2.751 Å). [15d] Since dialane(6) compounds on average have longer Al‐Al distances than dialane(4)s (Figure S1), the long Al‐Al distances in 3 and 5 are consistent with the large steric bulk of the ligands.

To understand why the Dipp‐substituted 3 b has a shorter Al−Al bond than its Mes analogue 5 b, we used an energy decomposition analysis. Multiple density functional theory methods, both with and without dispersion correction, underestimate the Al−Al bond in 5 b by ≈0.3 Å (e.g. M062X‐GD3/def2SVPP vs. X‐Ray: 2.581 vs. 2.886(2) Å, Table S6). We ascribe the difference between predicted (gas phase) and experimental Al‐Al distances to intermolecular dispersion interactions in the crystal structures. Indeed, a relaxed potential energy scan of the Al‐Al distance in 5 b (M062‐X‐GD3/def2SVP) reveals a minimal cost of 15 kJ mol−1 to increase the distance from the DFT‐optimized value to the experimentally observed one. Consistent with this, SAPT(2)/6–311G* computations on models of 3 b and 5 b extracted from M062X/Def2SVPP optimized geometries (Figure S3) revealed stabilizing intramolecular interactions of near identical magnitude. Although 3 b obtains greater stabilization from dispersion, this is offset by larger exchange interactions (Figure S3) leading to near identical stabilization overall (3 b, 5 b: −34.4, −32.7 kJ mol−1). Thus, we believe the differing solid‐state Al‐Al bond distances in 3 b/5 b arise from intermolecular dispersion in the crystalline material.

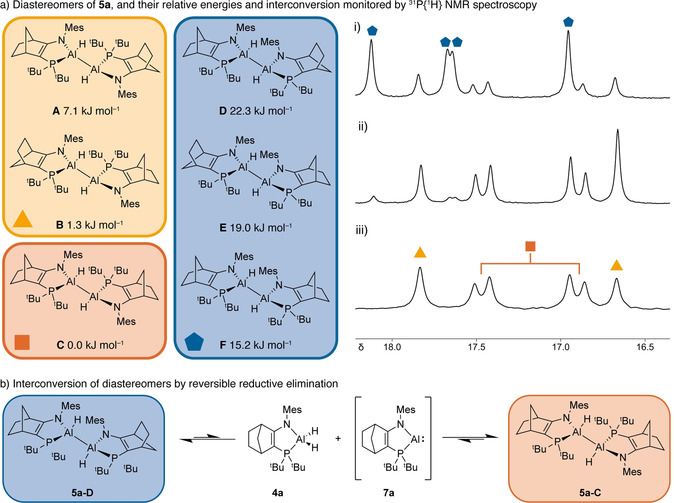

31P{1H} NMR spectroscopy of isolated 3 and 5 reveals they exist as mixtures of stereoisomers. Taking the NMes/PtBu2 coordinated dialane 5 a as an illustrative example, [21] crystalline samples dissolved in C6D6 give rise to a spectrum (Figure 3 a.iii) containing three resonances; two singlets at δ 17.8 and 16.7 and a pair of mutually coupled doublets at δ 17.5 and 16.9 (3 J PP=17.8 Hz). These resonances are ca. 10 ppm downfield from AlIII dihydride starting material 4 a. In the 1H NMR spectrum, a broad resonance is observed for the Al‐H groups at δ 5.1 (shifted downfield relative to AlIII dihydride 4 a: δ 4.6). Although the 1H spectrum is complex, certain distinctive resonances (e.g. mesityl‐CH3 groups and norbornene CH2 groups) again reveal the presence of three stereoisomers (see SI).

a) Diastereomers A–F of the dihydrodialane 5 a with relative energies by DFT (M062X/Def2SVPP); 31P{1H} NMR spectra for 5 a i) reaction mixture showing mixture of 5 a diastereomers A–F produced after reduction of 4 a at room temperature, ii) reaction mixture after reduction at 70 °C, iii) isolated crystalline 5 a in C6D6 solution. b) Proposed mechanism for interconversion of diastereomers by reversible reductive elimination and the AlI compound 7 a.

The spectroscopic situation is even more tortuous [22] when the reduction at room temperature of 4 a by [MesNacNacMg]2 is monitored by 31P{1H} NMR spectroscopy. In addition to the three stereoisomers in the crystalline samples of dialane 5 a, three other stereoisomers are also present, resulting in the observation of a total of 8 resonances (Figure 3 a.i). To understand these spectra, it is necessary for us to consider the possible stereoisomers of 5 a.

The dialanes 3 and 5 have 16 possible stereoisomers (although they contain 6 stereocenters, those on the norbornenyl backbone can be treated as a single center for our purposes), which on inspection reduce to the six diastereomers A–F (Figure 3 a) (see SI). In diastereomers A–C the phosphine ligands are located anti across the Al‐Al bond, the variation between A–C arising from the relative orientation of the norbornene CH2 bridges (e.g. “cis” or “trans”). A–C are the diastereomers present in crystallographically characterized 3 and 5, and those observed spectroscopically in solutions of isolated 5 a. Diastereomers A and B are meso compounds, due to the inversion center between the two Al atoms, rendering the phosphorus centers equivalent. We assign the singlets observed in the 31P{1H} NMR spectrum at δ 17.8 and 16.7 to these isomers. Diastereomer C has inequivalent phosphorus centers which we therefore assign to the doublets at δ 17.5 and 16.9.

Diastereomers D–F have the phosphorus ligands located syn about the Al−Al bond. These diastereomers are observed in solution alongside A–C when the room‐temperature reduction of the dihydride precursors is monitored by NMR spectroscopy, and the three isomers should result in four 31P NMR signals. The first two isomers D and E have equivalent phosphorus centers; F has two inequivalent phosphorus centers which could be expected to couple. The four expected resonances are found as singlets at δ 18.1, 17.7, 17.6 and 16.9; no doublets are observed for F, which we attribute to a decrease in the magnitude of 3 J P‐P as the P‐Al‐Al‐P torsion angle is reduced from ≈180° in C to ≈90° in F.

Consistent with the observation of all six diastereomers of 5 a in solution, and the experimentally observed order of stability, DFT calculations (M062X/Def2SVPP) reveal that diastereomers A–F fall within 23 kJ mol−1 of each other (Figure 3 a). Notably, the isomer with the lowest calculated energy, 5 a‐C, is also found as the major species in solutions of crystalline 5 a (≈60 % 5 a‐C, remainder 5 a‐A and 5 a‐B). Isomers D–F with syn phosphorus centers are higher in energy than A–C.

We carried out an energy decomposition analysis to deconvolute ligand/ligand interactions and reveal the origins of the preference for isomers A–C. SAPT(2)/6–311G* computations were used to decompose the interactions between ligands in models of the 5 a‐C/5 a‐F structures (geometries extracted from M062X/Def2SVPP optimized structures, see SI). Substantial stabilizing non‐covalent interactions were found to occur between the ligand N and P substituents (Figure S4). Whilst attractive dispersion interactions between the syn NMes groups in 5 a‐F contribute substantial stabilization (−20.9 of −50.0 kJ mol−1 total), this is opposed by a larger exchange repulsion component in this configuration (+59.9 kJ mol−1). Indeed, despite the anti 5 a‐C isomer that places NMes groups close to PtBu2 being less stabilized by dispersion (−34.4 kJ mol−1), it is overall more stable than 5 a‐F due to weaker exchange repulsion (+36.2 kJ mol−1). This general picture also holds for 3 a although the bulkier NDipp substituents result in overall lower stabilization from non‐covalent interactions (Figure S6).

The six stereoisomers of 5 a interconvert in solution. Mixtures of 5 a A–F, generated by reduction at room temperature, equilibrate over time. The process requires weeks at room temperature or 24 hours at 80 °C. It results in consumption of isomers D–F and production of thermodynamically favored isomers A–C. Lower quantities of D–F are also observed when reduction of 4 a is carried out at 70 °C (Figure 3 a.ii).

The interconversion of diastereomers A–F requires inversion of stereochemistry at the aluminum centers. We propose that this steroisomerisation proceeds by reductive elimination of an Al−H bond from dihydrodialanes (3 or 5) to generate the AlI intermediates (6 or 7) and the AlIII dihydrides (1 or 4) with destruction of the Al stereocentres (Figures 3 b and S8). Subsequent oxidative addition of an Al−H bond of the AlIII dihydrides 1 or 4 by AlI intermediate 6 (NDipp) or 7 (NMes) reforms the dihydrodialanes 3 or 5, thus regenerating two Al‐based stereocenters. Over time these processes bring mixtures of A–F to thermodynamic equilibrium.

Besides reversible reductive elimination, other mechanisms for inversion of stereochemistry at aluminum are conceivable. We can discount a mechanism involving inversion of stereochemistry at aluminum by reversible phosphine dissociation from one Al center on the basis that this pathway is unfavorable. We have already reported that the energetic cost for phosphine dissociation for a κ2‐(amidophosphine)AlH2 compound related to 1 a/b and 4 a/b is 83 kcal mol−1. [13] The Al‐Al bond in dialanes can dissociate photolytically, generating monomeric AlII radicals, [7] which could also explain interconversion of isomers A–F. We have no evidence for such a process in 3 or 5. In the case of the 5 a, isomers A–F equilibrate no faster when exposed to light than they do in the dark. Also, treatment with nBu3SnH does not generate the AlIII dihydrides 1 or 4 (as could be expected by H‐atom abstraction from nBu3SnH by an AlII radical).

Nikonov et al. reported the reductive elimination of Al−H bonds from III. [9] In this case, the equilibrium constant for reductive elimination is large enough to detect the AlI and AlII compounds II and III alongside the AlIII dihydride. In contrast, from 3 or 5 we did not observe AlIII or AlI species in equilibrium, indicating the equilibrium constant for their formation from 3 or 5 is low. Nevertheless, there is further experimental evidence for reversible Al‐H reductive elimination from dihydrodialanes 3 and 5.

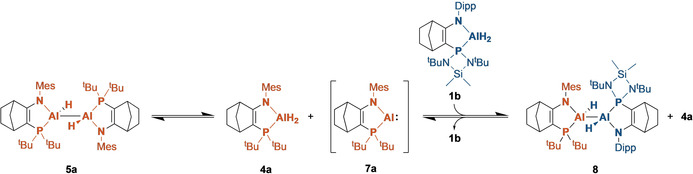

When a mixture of the PtBu2 AlII dihydrodialane 5 a and the P(NtBu)2SiMe2 AlIII dihydride 1 b in C6D6 was heated to 65 °C, formation of the “crossover” dialane 8 was observed (Scheme 2). Formation of this compound proceeds by reductive elimination of 4 a from 5 a, generating the AlI intermediate 7 a (not observed) which then reacts with 1 b to generate the mixed dialane 8. Both the dialane 8 (75.1–74.1 ppm) and the AlIII dihydride by‐product 4 a (8.7 ppm) are apparent in the 31P{1H} NMR spectrum. After 20 hours, the reaction generates an equilibrium mixture of the dialanes 5 a and 8 together with the AlIII hydrides 1 b and 4 a, which precluded isolation of 8. A quantity of the symmetrical P(NtBu)2SiMe2 dihydrodialane 3 b might also be expected, but was not detected, indicating 5 a and 8 are more stable. Similar “crossover” behavior was observed in the reactions of the dialane 5 a with the hydride triflates 2 a and 2 b (SI, p40).

“Crossover” experiment showing reaction between 5 a and 1 b to generate the “mixed” dihydrodialane 8 by reductive elimination from 5 a and oxidative addition to the proposed intermediate 7 a.

We also note here the related observation that reduction of the aluminum(III) hydride triflates 2 leads to formation of, besides dihydrodialanes 3 a and 3 b, the AlIII dihydrides 1 a or 1 b. The formation of the AlIII dihydride by‐products is explained by reductive elimination of Al−H bonds from the dialane product 3 under reaction conditions.

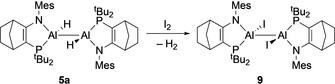

Very few reactions of dihydrodialanes or dialane(6) compounds have been reported. We thus investigated some rudimentary reactivity of the dihydrodialane 5 a. Reported dialane(4) compounds are oxidized by iodine. [15d] In contrast, when 5 a is treated with iodine the Al−H bonds are selectively iodinated in preference to the Al−Al bond, and diiododialane 9 is formed instead (Scheme 3). Crystallization of 9 from toluene solution allowed its solid‐state structure to be determined, revealing that replacement of the Al‐H substituents with iodides has minimal impact on the Al−Al bond distance or other structural features compared to 5 a (Al‐Al 5 a: 2.6586(16) Å; 9: 2.664(3) Å).

Reaction of 5 a with iodine to form AlII iodide dimer 9.

In summary, we have prepared a series of N,P‐coordinated dihydrodialanes. Increasing the steric bulk of the N or P substituents lengthens the Al‐Al bond distance. The stereocenters of AlII compounds 3 and 5 reveal the interconversion of diastereomers by reversible reductive elimination. This suggests that stereoactive ligands could be useful tools for probing “hidden” reversible reductive elimination processes elsewhere in main‐group chemistry, similar to the use of chiral silanes as mechanistic probes in B(C6F5)3 chemistry. [23] We are now investigating whether greater control of reductive elimination is possible by varying the nature of the donor ligand (phosphine in 3 and 5).

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This project has received funding from the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union's Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme (grant agreement no. ERC‐2016‐STG‐716315). We thank the Leverhulme Trust (Philip Leverhulme Prize to SLC). MJC and RLF would like to thank Prof. Andrew Lawrence for helpful discussions and stereochemical insight.

1

1a

1a

1b

1c

2

2a

3

3a

3a

3b

3c

5

5a

5a

5b

5b

5c

5c

11

11a

11a

11b

12

14

14

15

15a

15a

15b

15b

15c

15d

15e

16

16a

16b

16b

17

18

19

19a

19b

19c

20

21

22

23

23

24