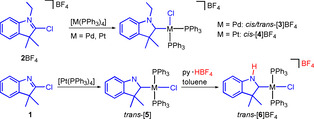

CAAC precursors 2‐chloro‐3,3‐dimethylindole 1 and 2‐chloro‐1‐ethyl‐3,3‐dimethylindolium tetrafluoroborate 2BF4 have been prepared and oxidatively added to [M(PPh3)4] (M=Pd, Pt). Salt 2BF4 reacts with [Pd(PPh3)4] in toluene at 25 °C over 4 days to yield complex cis‐[3]BF4 featuring an N‐ethyl substituted CAAC, two cis‐arranged phosphines and a chloro ligand. Compound trans‐[3]BF4 was obtained from the same reaction at 80 °C over 1 day. Salt 2BF4 reacts with [Pt(PPh3)4] to give cis‐[4]BF4. The neutral indole derivative 1 adds oxidatively to [Pt(PPh3)4] to give trans‐[5] featuring a CAAC ligand with an unsubstituted ring‐nitrogen atom. This nitrogen atom has been protonated with py⋅HBF4 to give trans‐[6]BF4 bearing a protic CAAC ligand. The PdII complex trans‐[7]BF4 bearing a protic CAAC ligand was obtained in a one‐pot reaction from 1 and [Pd(PPh3)4] in the presence of py⋅HBF4.

Cyclic (alkyl)(amino)carbene (CAAC) precursor salt 2BF4 reacts with [M(PPh3)4] (M=Pd, Pt) to give cis/trans‐[3]BF4 and cis‐[4]BF4, in which the CAAC ligand bears an unusual N‐alkyl substituent. trans‐[5] has a unique anionic CAAC ligand with an unsubstituted ring‐nitrogen atom which can be protonated to give trans‐[6]BF4 bearing a protic CAAC (pCAAC) ligand.

The preparation of cyclic (alkyl)(amino)carbenes (CAACs, A in Figure 1) by Bertrand in 2005 [1] added an interesting new derivative to the large family of N‐heterocyclic carbenes (NHCs, B in Figure 1). [2] Over the last years, various applications for CAAC ligands in transition metal coordination chemistry, catalysis and for the stabilization of reactive species have been described. [3] Compared to the ubiquitous N‐heterocyclic carbenes, CAACs feature special electronic properties, [3e] which also enable the activation of small molecules such as CO, [4] P4 [5] and even H2 or NH3. [6]

CAACs A and NHCs B.

Generally, CAACs of type A are obtained by C2‐deprotonation of cyclic aldiminium salts. Such salts are available from the reaction of aldimines with epoxides [1] or 3‐halogeno‐2‐methylpropenes [7] followed by acid catalyzed cyclization. While these routes have led to cyclic aldiminium salts and CAACs bearing various R and R′ groups at the quaternary carbon atom C3, the choice of the amino substituent is restricted to aromatic, bulky, electron‐withdrawing groups such as 2,6‐diisopropylphenyl. In addition, the sp3‐carbon atom C5 must be quaternary as C2‐deprotonation of the aldiminium cation would otherwise compete with deprotonation at C5. The replacement of one electronegative and planar π‐donating amino group in NHCs B for a tetrahedral σ‐ but not π‐donating alkyl group in the CAACs A make the latter ones both more nucleophilic (σ‐donating) and more electrophilic (π‐accepting). Computational studies show that the HOMO of CAACs lies slightly higher in energy than in NHCs and the singlet‐triplet energy gap in CAACs is slightly smaller than in NHCs. [6] CAAC complexes are normally prepared from the (in situ generated) free CAAC ligands and suitable metal complexes.

We became interested in the preparation of the currently unknown complexes bearing CAACs with aliphatic N1‐substituents or even a proton at N1. Given the instability of free CAACs in the absence of bulky aromatic substituents at N1, we assumed that the target N‐alkyl CAACs will not be stable in the free state and that complex preparation must therefore proceed via the in situ generation of the CAAC from a suitable precursor.

Various NHC complexes have been prepared by the in situ deprotonation of azolium salts in the presence of suitable metal complexes. Alternatively, but also without isolation of the free carbene, NHC complexes are accessible by the oxidative addition of the C2‐X bond (X=H, R, halogen) of azoles, azolium or pyrazolium cations to low valent transition metals. [8] The oxidative addition methodology has also been employed for the preparation of NHC complexes bearing the freely unstable protic NHCs (pNHCs) [9] or protic mesoionic NHCs. [10]

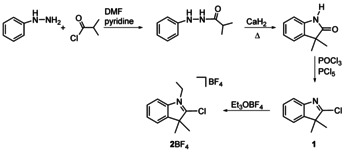

Encouraged by the versatility of the oxidative addition methodology, we prepared the halogenoindole derived, annulated CAAC precursors 1 [11] and 2BF4 [12] (Scheme 1, see the SI) for the preparation of CAAC complexes by an oxidative addition of the C2‐Cl bond to low‐valent transition metals.

Synthesis of CAAC precursors 1 and 2BF4.

Reaction of the 2‐chlorindolium salt 2BF4 with one equivalent of [Pd(PPh3)4] yielded the CAAC complex cis‐[3]BF4 in good yield (Scheme 2, top). The heterocyclic ligand features all characteristics of the known CAAC ligands of type A except for the C4‐C5 annulation and the unique N1‐alkyl substitution. Typical CAAC ligand properties were also observed in the 13C NMR spectrum of cis‐[3]BF4 featuring the downfield shifted resonance for the CCAAC carbon atom at δ(C2)=242.2 (cf the CNHC resonance at δ(C2)≈165–175 found in related NHC‐Pd complexes.[ 9a , 9d , 9e ]). The observation of a doublet of doublets for C2 (2 J CP,trans=141.9 Hz, 2 J CP,cis=5.7 Hz) indicates the cis‐disposition of the phosphine donors in cis‐[3]BF4. This cis‐arrangement was confirmed by the observation of two resonances in the 31P NMR spectrum at δ=29.8 (2 J PP=26.0 Hz, Ptrans) and δ=19.6 (2 J PP=26.0 Hz, Pcis). Some related complexes obtained from isoindolium salts (featuring cyclic (amino)(aryl)carbenes, CAArC)[ 7 , 13 ] or indazolium salts [14] have been described. However, these carbene ligands differ significantly from A or the CAAC ligand in cis‐[3]BF4 by the aromatic character of the carbon atom C3 which in both cases is part of a C3‐C4 annulated benzene ring.

![Oxidative Addition of 2BF4 to [M(PPh3)4].](/dataresources/secured/content-1765948864556-a6328c9b-12f8-415d-86d5-83f9ab8b25d4/assets/ANIE-60-2599-g005.jpg)

Oxidative Addition of 2BF4 to [M(PPh3)4].

The oxidative addition of 2BF4 to [Pd(PPh3)4] at an elevated temperature of 80 °C yields a complex mixture composed of trans‐[3]BF4 (major, about 60 %), cis‐[3]BF4 and [PdCl(PPh3)3]BF4 (Scheme 2, middle). While the components of the complex mixture could not be separated, the individual complexes in the mixture were identified by 31P NMR spectroscopy (see the SI). Complexes cis‐[3]BF4 and [PdCl(PPh3)3]BF4 were identified by comparison with the 31P NMR spectra of authentical samples while trans‐[3]BF4 gave the expected singulet resonance at δ=24.2. The temperature dependent formation of cis‐ and trans‐isomers has been previously observed during the oxidative addition of halogenoazoles to [M(PPh3)4] (M=Pd, Pt) complexes [9a] confirming that the CAAC ligands behave similarly to normal NHC ligands. Related observations have been made for palladium(II) complexes of type [Pd(rNHC)(PPh3)2I] (rNHC=pyrazolin‐4‐ylidene), where the initially formed cis‐diphosphine complex slowly transforms into the thermodynamically more stable trans‐complex. [9f] The preference for the trans‐complex has been rationalized by the transphobia effect, a term proposed for the difficulty of placing a phosphine donor trans to a carbon donor. [9g]

Finally, the oxidative addition of 2BF4 to [Pt(PPh3)4] yielded complex cis‐[4]BF4 (Scheme 2, bottom). Even at the elevated temperature of 110 °C, only the cis‐complex cation was observed in accord with the enhanced kinetic inertness of platinum(II) complexes. [9b] However, the reaction was completed after only 1 h and prolonged heating might also lead to the thermodynamically favored trans‐complex cation. [9a]

Compound cis‐[4]BF4 was characterized by NMR spectroscopy and by mass spectrometry (see the SI). The 13C NMR spectrum exhibits the resonance for the carbene carbon atom at δ(C2)=232.9 as the expected doublet of doublets (2 J CPtrans=126.7 and 2 J CPcis=8.2 Hz) for a cis‐diphosphine complex. The 31P NMR spectrum features two resonances at δ=15.5 (d, 2 J PP=20.4 Hz; d, 1 J PPt=2020 Hz, Pt satellites, Ptrans) and δ=11.1 (d, 2 J PP=20.4 Hz; d, 1 J PPt=3773 Hz, Pt satellites, Pcis) for the two chemically different phosphorus atoms. The HRMS spectrum (ESI, positive ions) shows the strongest peak at m/z=928.2363 (calcd for [4]+=928.2369).

The molecular structures of cis‐[3]BF4, trans‐[3]BF4⋅CH2Cl2 (Figure 2) and of cis‐[4]BF4 (see the SI, Figure S1) [16] have been determined by X‐ray diffraction, confirming the composition and coordination geometry of the complex cations. The metal atoms in the complexes are surrounded in a slightly distorted square‐planar fashion with the CAAC plane oriented almost perpendicular to the palladium coordination plane in all three cases.

![Molecular structures of complex cation cis‐[3]+ in cis‐[3]BF4 (left) and trans‐[3]+ in trans‐[3]BF4⋅CH2Cl2 (right). Hydrogen atoms have been omitted for clarity. Thermal ellipsoids are set at 50 % probability.

[16]

Selected bond lengths [Å] and angles (°) for cis‐[3]+ [trans‐[3]+]: Pd‐Cl 2.3374(7) [2.3512(9)], Pd‐P1 2.3956(7) [2.3721(10)], Pd‐P2 2.2838(7) [2.3591(9)], Pd‐C2 2.022(3) [1.996(3)], N‐C2 1.305(4) [1.310(5)], N‐C5 1.439(4) [1.446(5)], C2‐C3 1.518(4) [1.533(5)]; Cl‐Pd‐P1 84.12(2) [84.13(3)], Cl‐Pd‐P2 177.39(3) [85.28(3)], Cl‐Pd‐C2 84.85(7) [179.61(11)], P1‐Pd‐P2 98.48(2) [168.75(4)], P1‐Pd‐C2 168.95(7) [95.83(10)], P2‐Pd‐C2 92.56(7) [94.79(10)], C2‐N‐C5 113.4(2) [112.5(3)], N‐C2‐C3 108.3(2) [108.7(3)].](/dataresources/secured/content-1765948864556-a6328c9b-12f8-415d-86d5-83f9ab8b25d4/assets/ANIE-60-2599-g002.jpg)

Molecular structures of complex cation cis‐[3]+ in cis‐[3]BF4 (left) and trans‐[3]+ in trans‐[3]BF4⋅CH2Cl2 (right). Hydrogen atoms have been omitted for clarity. Thermal ellipsoids are set at 50 % probability. [16] Selected bond lengths [Å] and angles (°) for cis‐[3]+ [trans‐[3]+]: Pd‐Cl 2.3374(7) [2.3512(9)], Pd‐P1 2.3956(7) [2.3721(10)], Pd‐P2 2.2838(7) [2.3591(9)], Pd‐C2 2.022(3) [1.996(3)], N‐C2 1.305(4) [1.310(5)], N‐C5 1.439(4) [1.446(5)], C2‐C3 1.518(4) [1.533(5)]; Cl‐Pd‐P1 84.12(2) [84.13(3)], Cl‐Pd‐P2 177.39(3) [85.28(3)], Cl‐Pd‐C2 84.85(7) [179.61(11)], P1‐Pd‐P2 98.48(2) [168.75(4)], P1‐Pd‐C2 168.95(7) [95.83(10)], P2‐Pd‐C2 92.56(7) [94.79(10)], C2‐N‐C5 113.4(2) [112.5(3)], N‐C2‐C3 108.3(2) [108.7(3)].

The Pd‐C2 bond distance in trans‐[3]+ is significantly shorter than in cis‐[3]+ which is attributable to the weaker trans‐effect of the chloride ligand in trans‐[3]+ compared to the phosphine ligand in cis‐[3]+. Related observations were made for the Pd‐Cl bond distances where a short separation of 2.3374(7) Å was observed for cis‐[3]+ and a longer one of 2.3512(9) Å for trans‐[3]+. As expected, the CAAC donor exerts a stronger trans‐influence than the phosphine ligand. Due to the different ligand arrangements, the Pd‐P separations in cis‐[3]+ differ by about 0.112 Å while this difference amounts to only 0.013 Å in trans‐[3]+.

The metric parameters of the CAAC ligands are identical within experimental error in cis‐[3]+ and trans‐[3]+ and compare well to equivalent parameters observed in palladium complexes bearing non‐annulated CAAC ligands. [1] These include a C2‐C3 single bond (1.518(4) Å in cis‐[3]+ and 1.533(5) Å in trans‐[3]+), a significantly shorter N‐C2 bond (1.305(4) Å in cis‐[3]+ and 1.310(5) Å in trans‐[3]+) and N‐C2‐C3 angles of 108.3(2)° in cis‐[3]+ and 108.7(3)° in trans‐[3]+. Comparable metric parameters for cis‐[4]+ are very similar to those found for cis‐[3]+ (see the SI, Figure S1).

Apart from azolium cations,[ 8b , 8d ] neutral halogenoazoles can also oxidatively add to low‐valent transition metals to yield complexes bearing anionic azolato ligands,[ 9a , 9b , 9c , 9d , 9e ] which after N‐protonation yield complexes bearing neutral protic NHC (pNHC)[ 9a , 9c , 9d , 9e ] ligands. [15] In order to prepare the analogous but currently unknown complexes bearing N1‐protonated CAAC ligands, neutral 2‐chloroindole 1 was reacted with [Pt(PPh3)4] to give complex trans‐[5] bearing an anionic CAAC ligand with an unsubstituted ring‐nitrogen atom (Scheme 3, top). The trans‐disposition of the phosphine ligands in this case most likely results from the extended reaction time of 1 d (compared to only 1 h for the synthesis of complex cis‐[4]BF4). Treatment of the reaction product of the oxidative addition with py⋅HBF4 resulted in protonation of the ring‐nitrogen atom of the anionic CAAC ligand and formation of complex trans‐[6]BF4 bearing a unique protic CAAC ligand (pCAAC, Scheme 3, bottom).

![Synthesis of complexes trans‐[5] and trans‐[6]BF4.](/dataresources/secured/content-1765948864556-a6328c9b-12f8-415d-86d5-83f9ab8b25d4/assets/ANIE-60-2599-g006.jpg)

Synthesis of complexes trans‐[5] and trans‐[6]BF4.

The 13C NMR spectrum of trans‐[5] features the resonance for the carbene carbon atom as a triplet at δ(C2)=197.1 (t, 2 J CP=8.0 Hz), indicating the trans‐disposition of the phosphine donors. This resonance shifts significantly downfield to δ(C2)=221.4 (t, 2 J CP=7.6 Hz) in trans‐[6]BF4. In addition, the resonance for the N‐H proton was found in the 1H NMR spectrum of trans‐[6]BF4 at δ=12.33. Generally, all resonances in the NMR spectra shift downfield upon the transformation of trans‐[5] to trans‐[6]BF4 attributable to the introduction of a positive charge in trans‐[6]+. X‐Ray diffraction studies with crystals of trans‐[5]⋅CH2Cl2⋅C6H14 and trans‐[6]BF4⋅CH2Cl2 (Figure 3) [16] confirmed the conclusions drawn from NMR spectroscopy.

![Molecular structures of complex trans‐[5] in trans‐[5]BF4⋅CH2Cl2⋅C6H14 (left) and of one of two essentially identical complex cations trans‐[6]+ in the asymmetric unit of trans‐[6]BF4⋅CH2Cl2 (right). Hydrogen atoms have been omitted for clarity except for H1 at N in trans‐[6]+. Thermal ellipsoids are set at 50 % probability.

[16]

Selected bond lengths [Å] and angles (°) for trans‐[5] [trans‐[6]+]: Pt‐Cl 2.4056(5) [2.361(2)], Pt‐P1 2.3205(5) [2.3207(14)], Pt‐P2 2.3257(5) [2.332(2)], Pt‐C2 1.997(2) [1.974(8)], N‐C2 1.295(3) [1.302(10)], N‐C5 1.422(2) [1.428(10)], C2‐C3 1.561(3) [1.534(11)]; Cl‐Pt‐P1 87.17(2) [86.10(6)], Cl‐Pt‐P2 88.01(2) [87.01(7)], Cl‐Pt‐C2 174.09(6) [172.7(2)], P1‐Pt‐P2 164.76(2) [165.06(10)], P1‐Pt‐C2 93.50(6) [96.1(2)], P2‐Pt‐C2 92.77(6) [92.4(2)], C2‐N‐C5 108.1(2) [113.4(8)], N‐C2‐C3 113.1(2) [108.3(7)].](/dataresources/secured/content-1765948864556-a6328c9b-12f8-415d-86d5-83f9ab8b25d4/assets/ANIE-60-2599-g003.jpg)

Molecular structures of complex trans‐[5] in trans‐[5]BF4⋅CH2Cl2⋅C6H14 (left) and of one of two essentially identical complex cations trans‐[6]+ in the asymmetric unit of trans‐[6]BF4⋅CH2Cl2 (right). Hydrogen atoms have been omitted for clarity except for H1 at N in trans‐[6]+. Thermal ellipsoids are set at 50 % probability. [16] Selected bond lengths [Å] and angles (°) for trans‐[5] [trans‐[6]+]: Pt‐Cl 2.4056(5) [2.361(2)], Pt‐P1 2.3205(5) [2.3207(14)], Pt‐P2 2.3257(5) [2.332(2)], Pt‐C2 1.997(2) [1.974(8)], N‐C2 1.295(3) [1.302(10)], N‐C5 1.422(2) [1.428(10)], C2‐C3 1.561(3) [1.534(11)]; Cl‐Pt‐P1 87.17(2) [86.10(6)], Cl‐Pt‐P2 88.01(2) [87.01(7)], Cl‐Pt‐C2 174.09(6) [172.7(2)], P1‐Pt‐P2 164.76(2) [165.06(10)], P1‐Pt‐C2 93.50(6) [96.1(2)], P2‐Pt‐C2 92.77(6) [92.4(2)], C2‐N‐C5 108.1(2) [113.4(8)], N‐C2‐C3 113.1(2) [108.3(7)].

The protonation of the anionic CAAC ligand in trans‐[5] to give trans‐[6]+ has only a limited impact on comparable metric parameters. The most noticeable differences are the shrinkage of the N‐C2‐C3 angle from 113.1(2)° to 108.3(7)° and the expansion of the C2‐N‐C5 angle from 108.1(2)° to 113.4(8)° upon N‐protonation of trans‐[5]. Similar changes were observed upon protonation of coordinated azolato ligands to give complexes with pNHC ligands. [15]

Finally, 2‐chloroindole 1 was oxidatively added to [Pd(PPh3)4] in the presence of py⋅HBF4 to give trans‐[7]BF4 directly in a one‐pot reaction (Scheme 4). Compound trans‐[7]BF4 was fully characterized by NMR spectroscopy, ESI‐MS spectrometry and an X‐ray diffraction analysis (see the SI). [16] The 13C NMR spectrum shows the resonance for the CpCAAC carbon atom at δ(C2)=241.6 (t, 2 J CP=6.3 Hz) and the resonance for the N‐H proton was found at δ(H1)=12.45 in the 1H NMR spectrum. Comparable metric parameters in trans‐[3]BF4 (N‐ethyl substitution) and trans‐[7]BF4 (N‐H substitution) differ not significantly and confirm that the pCAAC in trans‐[7]+ behaves like a typical CAAC ligand.

![One‐pot synthesis of pCAAC complex trans

‐[7]BF4.](/dataresources/secured/content-1765948864556-a6328c9b-12f8-415d-86d5-83f9ab8b25d4/assets/ANIE-60-2599-g007.jpg)

One‐pot synthesis of pCAAC complex trans ‐[7]BF4.

We have prepared the 2‐chloroindole derived CAAC precursors 1 and 2BF4. In contrast to the classical synthesis of CAAC complexes by deprotonation of aldiminium salts followed by CAAC coordination to a metal center, these precursors can oxidatively add to zero‐valent transition metals. This procedure gives access to complexes bearing CAAC ligand with N‐substituents previously unattainable. From precursor 1, the first complexes bearing a CAAC ligand with an unsubstituted or a protonated ring‐nitrogen atom were obtained, while CAAC precursor 2BF4 yielded complexes with N‐alkyl‐substituted CAAC ligands.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

The authors gratefully acknowledge financial support from the DFG (SFB 858 and IRTG 2027). Open access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

1

1

2

2a

2a

2b

3

3a

3a

3c

3c

3d

4

4

5

5

6

7

8

8a

8b

8c

8d

8e

8e

8g

8h

9

9b

9c

9d

9e

9e

9f

9g

10

10

11

12

13

13

14

14a

14b

15

16