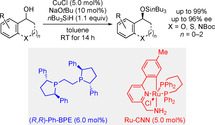

A nonenzymatic dynamic kinetic resolution of acyclic and cyclic benzylic alcohols is reported. The approach merges rapid transition‐metal‐catalyzed alcohol racemization and enantioselective Cu‐H‐catalyzed dehydrogenative Si‐O coupling of alcohols and hydrosilanes. The catalytic processes are orthogonal, and the racemization catalyst does not promote any background reactions such as the racemization of the silyl ether and its unselective formation. Often‐used ruthenium half‐sandwich complexes are not suitable but a bifunctional ruthenium pincer complex perfectly fulfills this purpose. By this, enantioselective silylation of racemic alcohol mixtures is achieved in high yields and with good levels of enantioselection.

The combination of a chiral copper catalyst and a bifunctional ruthenium pincer complex enables the nonenzymatic dynamic kinetic resolution of acyclic and cyclic benzylic alcohols. The enantioselective Cu‐H‐catalyzed dehydrogenative Si‐O coupling and the rapid transition‐metal‐catalyzed alcohol racemization are perfectly orthogonal. By this, high yields and good levels of enantioselection are achieved.

Dynamic kinetic resolution (DKR) is a powerful tool for the preparation of enantiomerically enriched chiral alcohols. [1] As an advantage over conventional kinetic resolution (KR) processes, the theoretical limit of 50 % yield for each enantiomer is overcome by rapid in situ racemization of the starting material. Tracing back to an early example by Williams and co‐workers, [2] this is typically achieved by catalytic transfer hydrogenation with only a few exceptions.[ 1a , 3 , 4 ] A particularly versatile racemization catalyst is ruthenium complex 1 developed by Bäckvall and co‐workers. [3a] In combination with Candida antarctica lipase B and isopropenyl acetate as the acyl source, efficient chemoenzymatic DKR of a number of structurally unbiased secondary alcohols was achieved (Scheme 1, top). Later, Fu and co‐workers succeeded in developing a DKR of secondary alcohols using Bäckvall's complex 1 and a ferrocene‐based, planar chiral DMAP derivative as a nucleophilic activator towards an acyl source (Scheme 1, middle). [5] This is the only nonenzymatic approach to date.

![Representative DKRs of alcohols by acylation (top) and planned silylation approach (bottom). DMAP=4‐dimethylaminopyridine, (R,R)‐Ph‐BPE=1,2‐bis[(2R,5R)‐2,5‐diphenylphospholan‐1‐yl]ethane.](/dataresources/secured/content-1765839800679-831a6b33-00ca-4b1e-93d7-1c4149d13b4f/assets/ANIE-60-247-g003.jpg)

Representative DKRs of alcohols by acylation (top) and planned silylation approach (bottom). DMAP=4‐dimethylaminopyridine, (R,R)‐Ph‐BPE=1,2‐bis[(2R,5R)‐2,5‐diphenylphospholan‐1‐yl]ethane.

The acyl group introduced by these DKRs is usually cleaved to liberate the free alcohol or occasionally used further as a protecting group. Silyl ethers excel at the protection of hydroxy groups owing to the ease of their installation and removal as well as their tuneable stability and orthogonality. [6] Unlike the numerous (D)KR processes by enzymatic and nonenzymatic enantioselective acylation,[ 1 , 5 ] corresponding silylation‐based methods had been unknown until approximately twenty years ago. [7] Starting from an initial report by Ishikawa, [8] asymmetric alcohol silylation has undergone tremendous advances. [7] Today, both organocatalytic [9] and transition‐metal‐catalyzed [10] approaches for the KR of alcohols are available. Conversely, suitable conditions for a related DKR have remained elusive (Scheme 1, bottom). For this, the resolving system and the racemization catalyst must be compatible, and racemization must occur significantly faster than the conversion of the slow‐reacting enantiomer to the product silyl ether. Additionally, the racemization catalyst must not promote any racemic background reactions, that is the racemization of the silyl ether and the coupling of the alcohol and the silylation reagent.

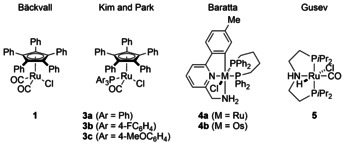

Our study commenced with an investigation of several ruthenium and osmium complexes as potential racemization catalysts with (S)‐1‐phenylethanol [(S)‐2 a] as the model substrate and benzene‐d 6 as the solvent (Figure 1 and Table 1). As expected, fast racemization of (S)‐2 a was seen using ruthenium complex 1 as the precatalyst and NaOtBu as the base (entry 1). The situation changed dramatically under our established KR conditions. The racemization was substantially slowed down in the presence of 6.0 mol % of (R,R)‐Ph‐BPE and stopped almost entirely when 1.3 equiv of nBu3SiH were added (entries 2–4). [12] A similar result was obtained with the structurally related, more robust ruthenium complex 3 a where one carbonyl ligand is replaced by triphenylphosphine (entry 5). [3b] The electronic modification of this complex using electron‐poorer and ‐richer phosphines as in 3 b and 3 c had no effect (entries 6 and 7). We then turned our attention towards bifunctional catalysts bearing a metal‐bound amino group that have been employed in transfer hydrogenation with great success. [13] In contrast to the half‐sandwich complexes 1 and 3 a–c operating through inner‐sphere mechanisms, [14] these catalysts likely operate through outer‐sphere mechanisms involving hydrogen‐bonding networks between the substrate and the NH2 functionality as a crucial feature. [15] In recent years, transition‐metal pincer complexes have emerged as highly active and robust catalysts, with [M(CNN)(dppb)Cl] 4 a (M=Ru)and 4 b (M=Os) as well as [Ru(PNP)(CO)HCl] 5 achieving particularly high turnover frequencies. [16] Also, ruthenium complex 5 was reported to facilitate the catalytic hydrogenolysis of chlorosilanes to produce hydrosilanes, [17] thereby making catalyst poisoning under our setup unlikely. Indeed, fast racemization of (S)‐1‐phenylethanol [(S)‐2 a] in the presence of both (R,R)‐Ph‐BPE and nBu3SiH was accomplished with all of the bifunctional catalysts 4 a, 4 b, and 5 (entries 8–10) and merely trace amounts of acetophenone were observed.

Candidates for catalytic alcohol racemization.

|

Entry |

Catalyst |

Variation |

ee [%][c] |

|---|---|---|---|

|

1 |

1 |

w/o (R,R)‐Ph‐BPE, nBu3SiH |

0 |

|

2 |

1 |

w/o nBu3SiH |

32 |

|

3 |

1 |

w/o (R,R)‐Ph‐BPE |

93 |

|

4 |

1 |

none |

95 |

|

5 |

3 a |

none |

93 |

|

6 |

3 b |

none |

94 |

|

7 |

3 c |

none |

90 |

|

8 |

4 a |

none |

0 |

|

9 |

4 b |

none |

0 |

|

10 |

5 |

none |

0 |

[a] All reactions were performed on a 0.1 mmol scale. [b] Estimated by in situ 1H NMR analysis; ratio based on the integration of baseline‐separated resonance signals. [c] Determined by HPLC analysis on a chiral stationary phase.

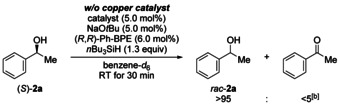

With three promising candidates as racemization catalysts in hand, we next investigated their activity in the aforementioned racemic background reactions (Scheme 2). Importantly, none of the pincer complexes catalyzed the racemization of the silyl ether (S)‐6 a in basic medium (Scheme 2, top). Additionally, both the Ru‐ and the Os‐CNN complexes 4 a and 4 b did not promote the dehydrogenative coupling of 1‐phenylethanol (2 a) and nBu3SiH (Scheme 2, bottom). Conversely, when Ru‐PNP complex 5 was employed as the precatalyst, substantial amounts of silyl ether 6 a were formed within 14 h, therefore thwarting its suitability for our endeavor. Without any obvious differences in catalytic activity between 4 a and 4 b, we continued with Ru‐CNN complex 4 a as the designated racemization precatalyst.

Interrogation of potential background reactions. All reactions were performed on a 0.2 mmol scale. Enantiomeric excesses were determined by HPLC analysis on a chiral stationary phase after cleavage of the silyl ether. Conversions were determined by GLC analysis using tetracosane as an internal standard.

We then tried the DKR of racemic 1‐phenylethanol (2 a) in the presence of a copper catalyst, employing ruthenium complex 4 a and our established resolving system consisting of CuCl, NaOtBu, (R,R)‐Ph‐BPE, and nBu3SiH in toluene. With 1.1 equiv of the hydrosilane, quantitative conversion of the alcohol was achieved after stirring for 14 h at room temperature, and the corresponding silyl ether (S)‐6 a was isolated with 86 % ee. It is worth noting that the reaction also proceeded smoothly in polar protic solvents such as tert‐amyl alcohol with unchanged reactivity and enantioselectivity (see the Supporting Information for details). However, reducing the reaction temperature to 0 °C did not improve the enantiomeric excess although good reactivity was maintained.

With suitable conditions established, we explored the scope of this DKR (Scheme 3). Various sterically and electronically modified benzylic alcohols 2 a–z were tested, and the corresponding silyl ethers (S)‐6 a–y were generally obtained in almost quantitative yields with good to high levels of enantioselection. Both electron‐donating (Me and OMe) and electron‐withdrawing substituents (aryl, heteroaryl, halogens, CF3, and CO2 tBu) were well tolerated but a trend regarding the reactivity or selectivity was not apparent. A detailed survey of the aryl group's steric effects revealed that monosubstitution of the parent 1‐phenylethanol (2 a) with methyl groups in the ortho‐, meta‐ and para‐positions as in 2 b, 2 d, and 2 f was compatible with only little influence on the enantiomeric excess. However, when a bulkier bromine atom was installed in either of these positions a more pronounced effect was observed. Here, ortho‐substituted (S)‐6 c was obtained with considerably lower ee, pointing towards a possible limitation of the racemization catalyst 4 a. Conversely, the enantioselectivities observed for meta‐ and para‐substituted derivatives (S)‐6 e and (S)‐6 j were in the expected range, yet noticeably higher in the former case. Accordingly, disubstitution in the meta‐positions led to the silyl ethers (S)‐6 n–p with improved enantioselectivities while ortho,ortho‐dimethylated (S)‐6 q was isolated with drastically reduced enantiomeric excess and after prolonged reaction time. The latter result stands in stark contrast to the outstanding selectivity factor of 170 observed in the KR of 2 q with the same copper catalyst. [10e] Consequently, steric bulk in the ortho‐position exerts a strong effect on the racemization ability of catalyst 4 a. In line with these findings, both α‐ and β‐naphthyl‐substituted derivatives 2 r and 2 s as well as alcohols bearing heterocyclic furan‐2‐yl and thien‐2‐yl units as in 2 t and 2 u exhibited high reactivity and good enantioselectivity. Although 1‐(pyridin‐4‐yl)ethanol (2 v) proved substantially less reactive, the enantiodifferentiation stayed in the same range. As expected from our previous work, [10e] both the enantiomeric excess and the reactivity dwindled with increasing size of the alkyl group Me < Et < Bn ≪ iPr [2 a and 2 w–y → (S)‐6 a and (S)‐6 w–y], and synthetically useful 2‐chloro‐1‐phenylethanol (2 z) was entirely unreactive. This trend was further corroborated in an application to 7, a precursor of duloxetine (gray box, left). The thien‐2‐yl unit had been shown to be compatible before [cf. 2 u → (S)‐6 u] but the ethylene‐tethered, Boc‐protected amino group was detrimental, affording (S)‐9 with moderate 62 % ee; the coordination ability of the Boc group could however contribute to this outcome. In another application, carbamate‐containing 8 participated in the DKR with good efficiency to yield the rivastigmine precursor (S)‐10 in 93 % ee (gray box, right).

![DKR of acyclic benzylic alcohols. All reactions were performed on a 0.2 mmol scale. Yields are isolated yields after flash chromatography on silica gel. Enantiomeric excesses were determined by HPLC analysis on chiral stationary phases after cleavage of the silyl ether. [a] The reaction time was 48 h. [b] Estimated enantiomeric excess since no baseline separation was achieved. [c] The reaction time was 36 h. [d] The reaction time was 84 h. [e] The reaction time was 60 h. Boc=tert‐butoxycarbonyl.](/dataresources/secured/content-1765839800679-831a6b33-00ca-4b1e-93d7-1c4149d13b4f/assets/ANIE-60-247-g005.jpg)

DKR of acyclic benzylic alcohols. All reactions were performed on a 0.2 mmol scale. Yields are isolated yields after flash chromatography on silica gel. Enantiomeric excesses were determined by HPLC analysis on chiral stationary phases after cleavage of the silyl ether. [a] The reaction time was 48 h. [b] Estimated enantiomeric excess since no baseline separation was achieved. [c] The reaction time was 36 h. [d] The reaction time was 84 h. [e] The reaction time was 60 h. Boc=tert‐butoxycarbonyl.

Selected aliphatic alcohols were also included into this study (Figure 2), especially to compare 1‐phenylethanol (2 a) with fully saturated 1‐cyclohexylethanol. The corresponding silyl ether (S)‐11 a (79 % ee) did form with slightly diminished ee compared to (S)‐6 a (86 % ee), and the reaction had a significantly smaller rate (days versus hours). Both substitution of the cyclohexyl moiety with a cyclopentyl group (as in (S)‐11 b) and slight chain elongation (i.e. Me → Et as in (S)‐11 c) paired low reactivity with further deteriorated enantioselectivity, and full conversion was not even reached in the latter case.

![DKR of aliphatic alcohols. All reactions were performed on a 0.2 mmol scale. Yields are isolated yields after flash chromatography on silica gel. Enantiomeric excesses were determined by HPLC analysis on a chiral stationary phase after cleavage of the silyl ether and derivatization as the p‐nitrobenzoate. [a] The reaction time was 84 h. [b] The reaction time was 120 h after which 65 % conversion of 1‐cyclohexylpropanol was detected by GLC analysis using tetracosane as an internal standard. [c] Estimated enantiomeric excess since no baseline separation was achieved.](/dataresources/secured/content-1765839800679-831a6b33-00ca-4b1e-93d7-1c4149d13b4f/assets/ANIE-60-247-g002.jpg)

DKR of aliphatic alcohols. All reactions were performed on a 0.2 mmol scale. Yields are isolated yields after flash chromatography on silica gel. Enantiomeric excesses were determined by HPLC analysis on a chiral stationary phase after cleavage of the silyl ether and derivatization as the p‐nitrobenzoate. [a] The reaction time was 84 h. [b] The reaction time was 120 h after which 65 % conversion of 1‐cyclohexylpropanol was detected by GLC analysis using tetracosane as an internal standard. [c] Estimated enantiomeric excess since no baseline separation was achieved.

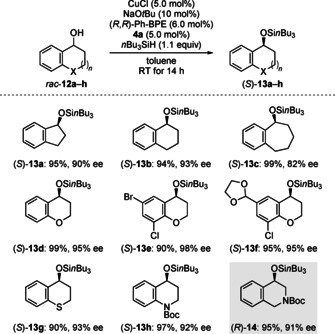

Finally, we investigated cyclic benzylic alcohols 12 a–h with different ring sizes as substrates for our reaction (Scheme 4). Again, yields were nearly quantitative and enantioselectivities were usually slightly better than for their acyclic counterparts. Hence, five‐ to seven‐membered carbocyclic alcohols 12 a–c smoothly underwent the reaction, although the benzosuberol‐derived silyl ether (S)‐13 c was obtained with notably lower ee. Substitution with a heteroatom in the saturated ring was also tolerated, and the highly functionalized (thio)chromanol‐derived silyl ethers (S)‐13 d–f and (S)‐13 g were amenable with high ee. Furthermore, the position of the heteroatom had no significant effect on the selectivity of our reaction as evident from the tetrahydro(iso)quinolinol‐derived silyl ethers (S)‐13 h and (R)‐14 (gray box).

DKR of cyclic benzylic alcohols. All reactions were performed on a 0.2 mmol scale. Yields are isolated yields after flash chromatography on silica gel. Enantiomeric excesses were determined by HPLC analysis on chiral stationary phases after cleavage of the silyl ether.

DKR of secondary alcohols is typically achieved by enantioselective acylation techniques for which several chemoenzymatic protocols are available. [1a] Fu's nonenzymatic process had remained an isolated example [5] and is also a beautiful example of orthogonal tandem catalysis. [18] A cognate tool relying on the stereoselective silylation of alcohols has been unprecedented so far. We reported here a DKR of secondary alcohols by means of a Cu‐H‐catalyzed dehydrogenative coupling with the simple hydrosilane nBu3SiH. The choice of the racemization catalyst is crucial as commonly used ruthenium half‐sandwich complexes fail under our previously established, commercially available resolving system. [10e] In turn, bifunctional ruthenium and osmium pincer complexes were identified as suitable alternatives and were successfully combined with our KR procedure. [10e] Our method is applicable to a broad range of acyclic and cyclic benzylic alcohols and exhibits good functional‐group tolerance. An extension of this approach to allylic[ 10e , 19 ] and propargylic [10f] alcohols will require further catalyst design and is currently under investigation in our laboratory.

J.S. and M.O. filed a patent application of the reported method.

This research was supported by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (Oe 249/14‐1) and the Fonds der Chemischen Industrie (predoctoral fellowship to J.S., 2018–2020). M.O. is indebted to the Einstein Foundation Berlin for an endowed professorship. We thank Takuya Kinoshita of Osaka University for his experimental contributions. Open access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

1

1b

1b

1c

2

3

3a

3d

3e

3e

3f

3g

3g

4

4a

4b

4c

4c

6

6a

6b

7

7a

7c

7c

8

9

9a

9a

9d

10

10a

10a

10b

10b

10d

10d

10f

10f

11

12

15

16

16a

16a

16b

16b

16c

17

18

19